“An analysis of the revised MPEP reveals that it contains multiple changes that not only fail to address the President’s and Senators’ concerns, but instead actively facilitate more restriction thickets.”

In July 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order to ensure that “the patent system, while incentivizing innovation, does not also unjustifiably delay generic drug and biosimilar competition beyond that reasonably contemplated by applicable law.” Nearly a year later, in June 2022, six United States Senators sent a letter to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), raising concern about “large numbers of patents that cover a single product or minor variations on a single product, commonly known as patent thickets.”

In July 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order to ensure that “the patent system, while incentivizing innovation, does not also unjustifiably delay generic drug and biosimilar competition beyond that reasonably contemplated by applicable law.” Nearly a year later, in June 2022, six United States Senators sent a letter to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), raising concern about “large numbers of patents that cover a single product or minor variations on a single product, commonly known as patent thickets.”

Patent thickets can occur when the USPTO issues multiple commonly owned patents covering similar subject matter. As exposed by Professor Adam Mossoff, much concern over patent thickets in the pharmaceutical space seems to stem from unverified and unreliable drug patent numbers published by organizations like the Initiative for Medicines, Access & Knowledge (I-MAK). However, even when drug patent numbers are properly accounted for by organizations such as BIO, patent thickets are often seen as unjustly extending patent rights at the expense of the public. Multiple patents on indistinguishable inventions can deter innovators, investors and competitors from entering the field, even after earlier-granted patents expire.

Much of the attention on patent thickets has been focused on those created by applicants who file multiple continuation applications on similar subject matter. The USPTO has a remedy for such “continuation thickets”: the non-statutory double patenting (NSDP) rejection which applicants can overcome by filing a terminal disclaimer (TD). A TD ties continuation patents together with a requirement to be co-owned and a single expiration date limiting patent term — generally that of the earliest-filed patent.

The Lesser-Known Thicket

However, another type of potentially more problematic patent thicket has received less attention. “Restriction thickets” are prompted by patent examiners issuing restriction requirements that overly narrow the subject matter applicants are permitted to elect to pursue in a single application. Such restriction practice drives applicants to file additional applications directed to (oftentimes multiple) non-elected groups or species of inventions “divided out” of the original application. In effect, such examiner-imposed restriction requirements expressly authorize applicants to create restriction thickets consisting of separate divisional applications with claims to the non-elected subject matter. Because the restriction requirement deems the divided out subject matter “patentably distinct,” examiners are prohibited from making NSDP rejections between the restricted applications and/or patents. This means, each divisional is typically shielded by the “safe harbor” of 35 U.S.C. § 121. Since they are not bound together by a TD, the resulting original and divisional patents can have different enforceable terms and/or different ownership.

Restriction thickets are of particular concern for chemical, pharmaceutical and biotechnology applications examined in USPTO Technology Center (TC) 1600. As compared to continuation thickets, restriction thickets thus have a greater potential to evergreen pharmaceutical patents, postpone a drug’s production by generic companies, and keep drug prices high.

The Request for Comments

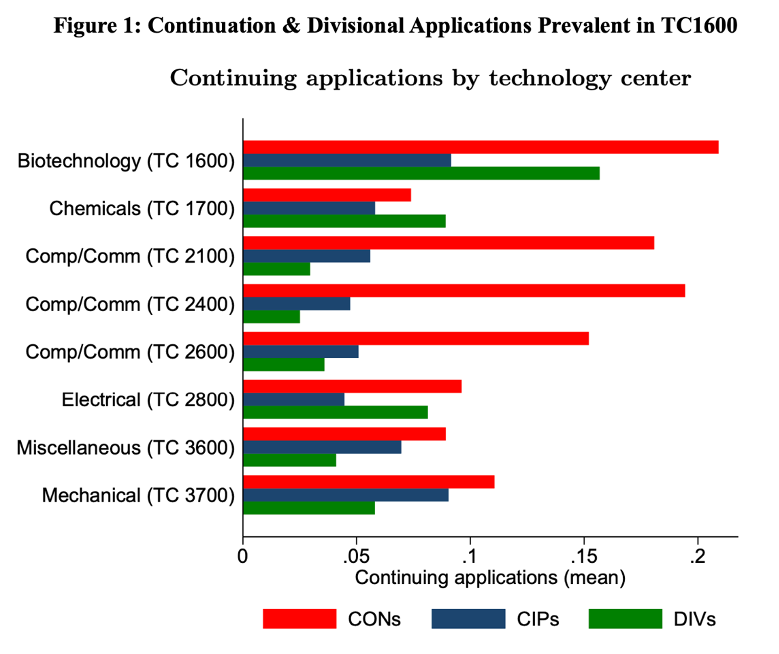

The USPTO’s October 2022 Request for Comment (RFC), titled “USPTO Initiatives to Ensure the Robustness and Reliability of Patent Rights,” relies on corps-wide statistics to assert that the growing number of continuations are the problem, not divisional applications, which have declined since 2010. Drilling down into the TC-level, a significantly higher incidence of both divisional and continuation applications is found in TC1600 than in other TCs. Figure 1 is reproduced from Continuing Patent Applications at the USPTO’s Figure 2 published Jan. 2023.

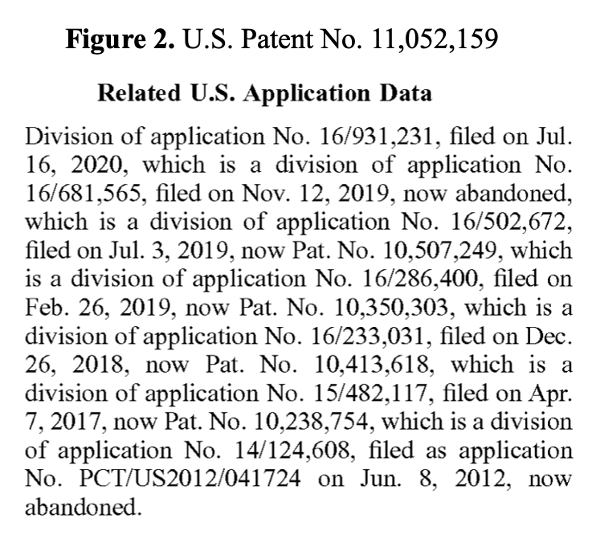

TC1600, which examines patent applications related to human pharmaceuticals and diagnostics, historically exhibits the highest rates of restriction practice. The RFC relies upon feedback to suggest that restriction practice is the reason for many continuing applications being filed but does not acknowledge the role restriction practice plays in divisional applications and resulting restriction thickets. It should be noted that restriction practice is a longstanding and useful USPTO tool and does not necessarily produce patent thickets. The existence of multiple serial divisional applications (as illustrated by the related application data shown in Figure 2) may suggest a restriction thicket but is not determinative.

The RFC specifically sought input on key drivers underlying patent thickets, including specific policies and procedures pertaining to restriction practice. See Table 1.

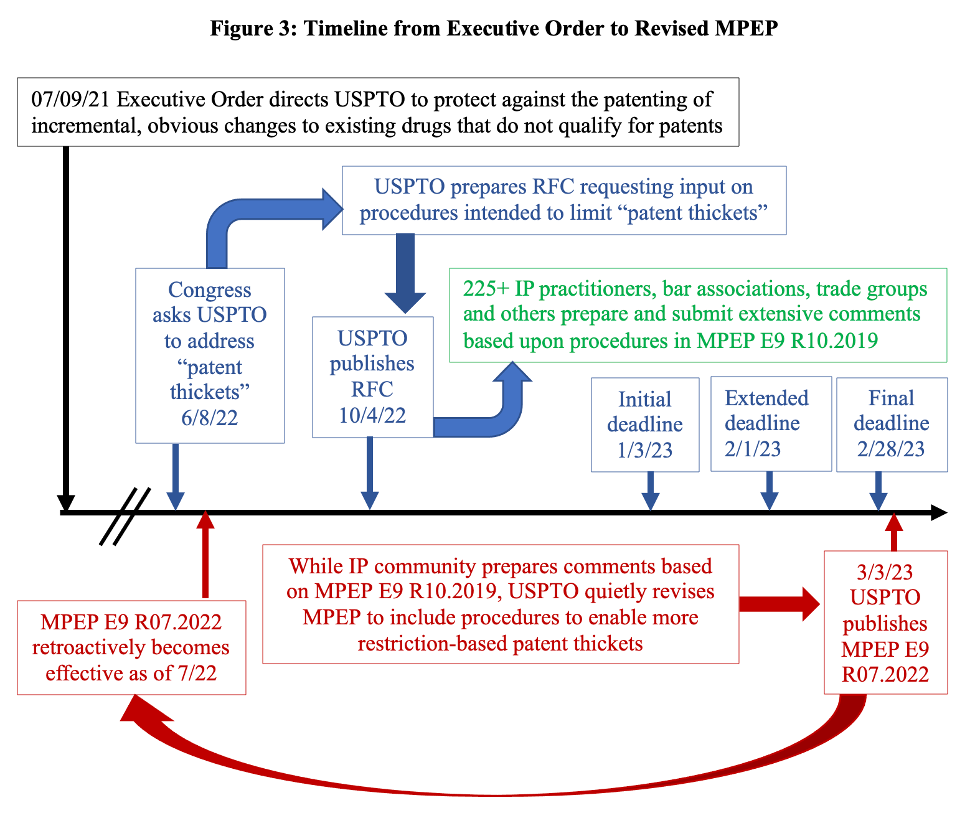

Patent practitioners, IP bar associations, trade organizations, inventors and others responded to the RFC by filing more than 225 comments in advance of the February 28, 2023 extended deadline. The posted comments demonstrate great interest in the proposed changes which, if adopted, would place extensive burdens on the IP community. During the response period, restriction practice was guided by the version of the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) that was then public at the time, i.e., Ninth edition, revision 10.2019.

MPEP Revisions

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, the USPTO was actively working to revise sections of that version of the MPEP pertaining to the very subject of the RFC, including policies and procedures relating to restriction, continuation, divisional, double patenting and terminal disclaimer practice. Three days after the RFC response period ended, the USPTO announced publication of a revised version of the MPEP in the Federal Register. The revised MPEP (Ninth edition, revision 07.2022) was made retroactive to July 2022. A timeline summarizing events from the Executive Order to the USPTO’s publishing of the revised MPEP is shown in Figure 3.

The specific changes made in the revised MPEP appear to have arisen without any public notice or comment period, and without publication of any intervening memorandum to the examining corps or interim guidance. Although subscribers to Patent Alerts would have received an emailed announcement, the USPTO’s News and Updates and Patent Examination Policy Announcement webpages do not mention the revised MPEP. And most importantly, even though the revised MPEP has an effective date of July 2022, RFC commenters did not have access to it when they prepared and filed their comments.

In response to inquiry from this author, a Senior Legal Advisor in the USPTO Office of Patent Legal Administration confirmed that “The MPEP revisions published in February 2023 have a revision indicator of [R-07.2022], meaning that they reflect USPTO patent practice and relevant case law as of July 31, 2022…Because the Robust & Reliable RFC (87 FR 66282) did not publish until several months later (October 2022), it is not reflected in the MPEP.” Nor was the RFC reflective of the MPEP revisions effective as of July 31, 2022.

MPEP changes can be easily overlooked. In 2014, the USPTO unfortunately discontinued its prior practice of providing revision marks and thus no marked up version is available on the USPTO’s webpage. A 64-page Change Summary intermixes important procedural changes with long lists of minor changes addressing typographical errors, grammatical glitches and erroneous case citations. The Change Summary uses the term “must” and variations on the term “require” 54 and 108 times, respectively, suggesting that many of the new procedural changes place obligations or constraints on patent practitioners. The phrases “restriction requirement,” “double patenting,” and “terminal disclaimer” occur 25, 38, and 14 times, respectively, in the Change Summary, indicating that many of the changes are directed to policies and procedures under consideration in the RFC.

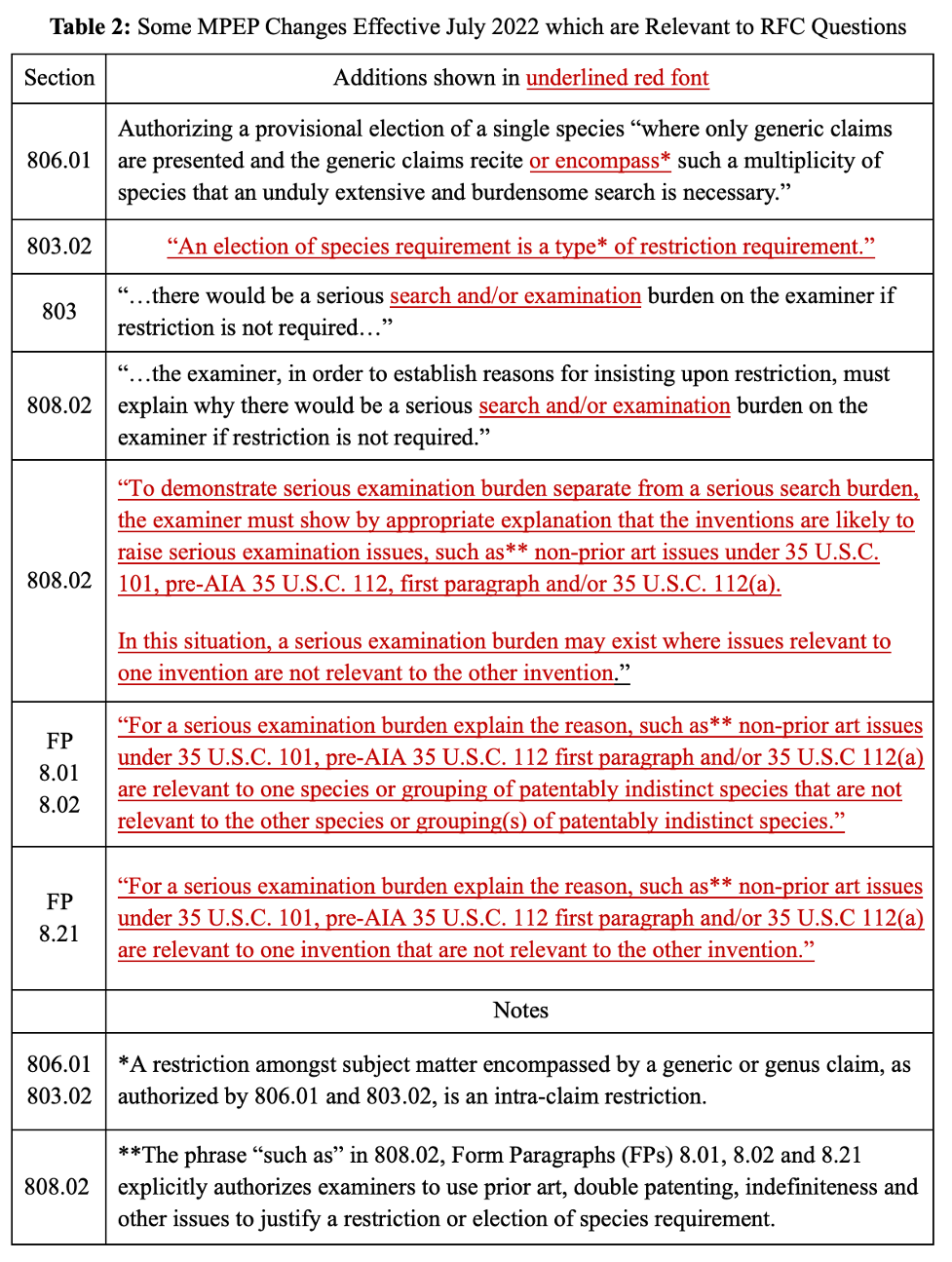

An analysis of the revised MPEP reveals that it contains multiple changes (see Table 2) that not only fail to address the President’s and Senators’ concerns, but instead actively facilitate more restriction thickets.

How do the MPEP Changes Promote Restriction Thickets?

As a hypothetical example, consider a drug application having one genus claim reading “A method of treating cancer by administering a compound of Formula 1.” As revised, MPEP 806.01 now explicitly authorizes examiners to use restriction practice to require applicants to elect (i) a species of cancer and (ii) a species of compound from the various cancers and compounds encompassed by Formula 1 disclosed in the specification.

In this hypothetical example, it’s likely that examination of the genus claim under the prior version of the MPEP would not present the examiner with a serious search burden that would justify restriction, since the species of cancers and compounds would likely fall into the same searchable class and subclass. Revised Sections 803.02, 808.02 and Form Paragraph (FP) 8.02 now expand serious burden beyond search burden to also include examination burden, making it easier for the examiner to justify imposing a restriction requirement.

Some applicants would rightfully object to having their genus claim divided up into little pieces. As explained by Mossoff and Dowd, genus claims have played a pro-innovation role in every technological revolution and their subsequent advances.

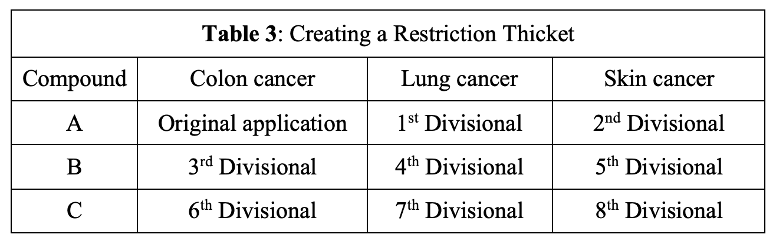

Other applicants would welcome this type of intra-claim restriction and amend the original generic claim accordingly to identify a species of cancer and compound, e.g.: “A method of treating colon cancer by administering [a] compound A of Formula 1.” Because MPEP 803.02 now explicitly identifies an election of species requirement as a type of restriction requirement, applicants are on stronger footing to file a series of future divisional applications directed to various non-elected species of cancer and compound, e.g., as shown in Table 3.

Since the hypothetical divisional applications summarized in Table 3 are directed to examiner-sanctioned “patentably distinct” subject matter, MPEP 804 prohibits NSDP rejections, and no terminal disclaimers can be required. The resulting nine patents, which would cover closely related subject matter encompassed by the original genus claim, can then be separately owned, separately enforced and given separate patent terms.

Why would examiners use restriction so aggressively? Because it benefits them, too. Examiners have inherent incentives to divide applications to maximize their opportunity to earn counts on the divisional applications where they are already familiar with the subject matter of the disclosure. In fact, in 2021, the USPTO revised the quality element of the examiner’s Performance and Appraisal Plan to incentivize examiners to make “a complete restriction/election requirement in the initial restriction/election” (emphasis added) as indicia for higher performance ratings. Additional patents also result in additional maintenance fees, providing a financial incentive to the USPTO.

Contentious History of Examination Burden

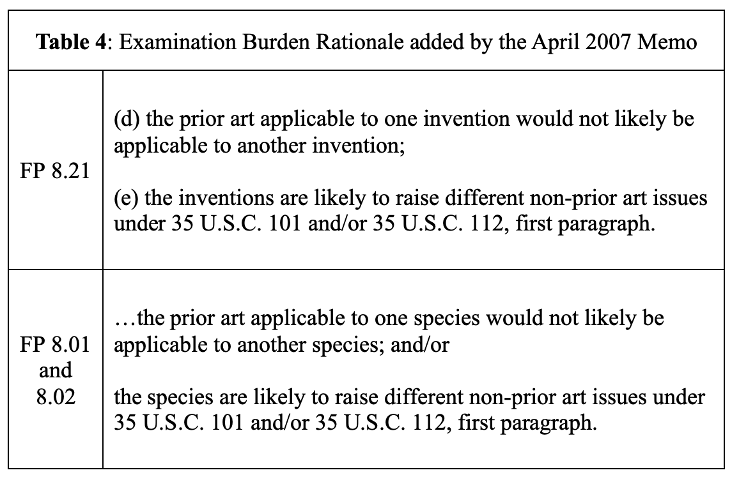

The scope of “serious burden” is not defined by rule or statute and has been the subject of prior debate. Without notice and comment, former Director Jon Dudas relaxed the serious burden criteria to include examination issues via an April 2007 memo. Table 4 shows examination burden rationale added to the examiners’ form paragraphs.

As former Commissioner for Patents John Doll ofttimes quipped, this policy change encouraged examiners to “slice the claims thin as salami.”

Internally, the April 2007 policy changes were disputed by this author and others for (i) promoting more restriction requirements, (ii) tainting applications with substantive examination issues that could not be resolved via response to the restriction requirement and (iii) potentially creating a catch-22 situation when a specific combination or subgenus identified by the examiner in the restriction requirement is elected and then rejected for lacking adequate written description or enablement.

The USPTO rescinded the April 2007 memo in a January 2010 memo that removed examination burden reasons as inconsistent with MPEP 808.02. In response to the 2010 Federal Register Notice concerning proposed changes to restriction practice, practitioners submitted extensive feedback directed at the 2007 and 2010 memos, including comments questioning the agency’s lack of compliance with the Administrative Procedure Act. Flash forward to 2023, the USPTO has again, without public notice and comment, relaxed restriction practice in a variety of ways that were not disclosed in the concurrently operating RFC.

What have Commenters Requested?

Commenters including the Innovation Alliance, AIPLA, IPO, and patent attorney Drabnis, among others, support enforcing or strengthening the existing serious burden requirement to reduce the number of divisional applications. Instead, the USPTO has loosened restriction policies beyond what is reasonably contemplated by applicable law in a manner that runs directly counter to many RFC comments.

The revised MPEP changes to restriction practice create serious burden for applicants—who get less examination for their initial filing fees and are often required to file more applications to have the subject matter encompassed by their original genus claim examined—and the public alike—who face higher drug costs when USPTO-created restriction thickets improperly extend drug patent rights.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Breeze

March 21, 2023 10:15 am“To be fair, it is worth noting that writing restrictions require time,…”

In 23+ years of practice I have yet to see a restriction requirement that could have possibly taken longer than the allotted one hour of non-examining time to write. Most are so brain dead silly that it defies any credulity to even suggest any actual thought or analysis went into them.

Julie Burke

March 17, 2023 10:46 amThanks, David, for highlighting the amount of time it takes for an examiner to write a restriction requirement. I’d agree.

The production element of the examiner’s Performance and Appraisal Plan actively encourages examiners to engage in a cost-benefit analysis when deciding whether or not to require applicants to pick a group of claims or elect a species for examination. The USPTO awards examiners one hour “other time” whenever they mail a written restriction or election of specific requirement, even if the requirement is made as part of an office action on the merits (i.e., refusing to examine newly added claims they’ve withdrawn by original presentation).

Batch restricting 8 applications, tallied as 8 hours of other time work to cover a whole day’s production goals, has historically been considered a great way for an efficient examiner to “built their own docket.”

The subsequent search and examination of each restricted application, and resulting continuations and divisionals, will likely require less time and effort on the examiner’s part per application, than if the original application had been examined in full.

Of course, the applicant needs to pay full filing, search and examination fees anew for each of these additional applications.

And each resulting patent is subject to maintenance fees beyond what would have been required for the original patent, even if the cases are later TD-ed together.

So looking at it this way, restriction can be viewed as a tool used by the examining corps and USPTO management to (i) help meet production goals and (ii) qualify for cash bonuses and (iii) bring more money into the user-fee funded agency.

So yes, it’s likely a real cost-benefit analysis goes on each time a restriction or election of species is required.

Perhaps USPTO leadership had this cash incentive in mind when they quietly loosened up the serious burden requirement to permit more restriction and election of species requirements?

David Lewis

March 16, 2023 04:40 pmTo be fair, it is worth noting that writing restrictions require time, and so there is a cost-benefit analysis that an examiner typically does prior to writing a restriction (even if the analysis is done based on “gut” feelings).

however, restriction requirements become particularly problematic when essentially no complete embodiments fit into any identified grouping.

Similarly, when no one grouping contains more than 2 or 3 claims, something is wrong, because that says that examining more than 2 or 3 claims is somehow too burdensome. This is especially problematic, when the Applicant makes an honest attempt to add more claims directed to the elected invention, and then the Examiner further restricts the new claims so that the Applicant is still left with less than a hand full of claims. This sort of restriction practice also lends itself to allowing the examiner to use restriction practice instead of prior art to limit amendments that can overcome the prior art, which defeats the purpose of 102, 103, and potentioanlly 101 and 112.

Pro Say

March 14, 2023 06:27 pmWhew! Thank goodness we’ve got Vidal working tirelessly to make right all that is wrong with the Patent Office!

Sure we do.

Julie Burke

March 14, 2023 12:27 pmyes & by retroactively revising MPEP 803.02 to authorize more intra-claim restrictions & by relaxing the burden criteria in MPEP 808.02 to authorize more restriction & election of species requirements, said changes made DURING an ongoing Request for Comments on these very topics, one wonders if anybody at the USPTO understand the basic sequence of events required for public notice & comments on proposed policy changes?

USPTO, here’s what should have happened:

First, provide notice of specific proposed changes

Second, gather comments from stakeholders

Third, review & analyze the comments

Fourth, propose changes based upon review & analysis of the comments

Fifth, publish changes that are to be effective moving forward, not retroactively.

Jiminy crickets, isn’t it time the USPTO stop playing games with America’s IP?

Breeze

March 14, 2023 09:28 amMPEP 803.02 is proof beyond any shadow of a doubt that nobody at the PTO understands sections 112(b) and 121.