“This data shows that the PTAB is almost three times more likely to side with a petitioner’s expert on the majority of issues in a case than with the patentee’s expert.”

Patent owners think Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs) are a fixed game. Their concern goes beyond structural and procedural aspects of the IPR process; patent owners also believe that Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) judges are hostile to patents. Their concerns are particularly pronounced because their opportunities for appellate review of those PTAB judges’ decisions is limited. This article examines whether this concern is justified.

Patent owners think Inter Partes Reviews (IPRs) are a fixed game. Their concern goes beyond structural and procedural aspects of the IPR process; patent owners also believe that Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) judges are hostile to patents. Their concerns are particularly pronounced because their opportunities for appellate review of those PTAB judges’ decisions is limited. This article examines whether this concern is justified.

IPRs and Appellate Review

Some aspects of IPRs are similar to those of district court patent proceedings. Parties battle over the same Section 102/103 issues, often relying heavily on expert opinions as in the district courts. PTAB panels then adjudicate the factual and legal issues. Appeals are to the Federal Circuit.

A legal standard deferential to the PTAB panel governs appeals. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, PTAB determinations stand as long as “substantial evidence” supports them. “Substantial evidence” means “more than a scintilla but less than a preponderance”, a standard that is easy for the party arguing to affirm the PTAB to satisfy in practice.

Overturning PTAB IPR determinations, therefore, is hard. If at least some evidence supports the PTAB’s conclusion, the Federal Circuit will affirm. And because IPRs so often involve expert opinion evidence on every disputed factual issue, there almost always is at least some supporting evidence.

This kind of appellate deference to agency decision-making exists throughout the American legal system and usually makes sense. Where witnesses testify in person, the body seeing the testimony can judge credibility better than an appellate panel limited to the paper record. Administrative agencies also may have specific expertise that a generalist appellate body does not. Of course, deference depends on an underlying assumption that the lower court or agency is unbiased.

There’s a question, however, about whether such deference makes sense with IPRs. There’s no live testimony in the IPR process, with experts merely submitting written reports. And the Federal Circuit has at least as much patent expertise as PTAB administrative patent judges. That leaves the question of bias, which this analysis evaluates.

Analysis

To look for signs of potential bias, I began with 226 final PTAB decisions from January 1, 2022, through June 30, 2022. (There were 237 total decisions, but 11 of them had either large portions redacted and/or formatting issues that made the analysis detailed in this article impossible for them). I then limited myself to the 170 IPR decisions where both the petitioner and patent owner submitted expert reports. Typically, the petitioner will retain a technical expert, who submits a report explaining how, in the expert’s opinion, the prior art satisfies every limitation of each challenged claim. Often, but not always, the patentee will then retain an expert to submit a contrary report, one opining that one or more limitations are absent.

Focusing on these “dueling expert” IPRs was the best way to ensure that both sides were on roughly equal footing and to eliminate reasons for a lack of balance in outcomes. When only one side pays an expert, it could mean an imbalance of resources between the parties. Moreover, a patent owner’s failure to hire an expert could be based on the owner’s view that its patent did not warrant that kind of investment. Finally, an expert on only one side creates an evidentiary imbalance.

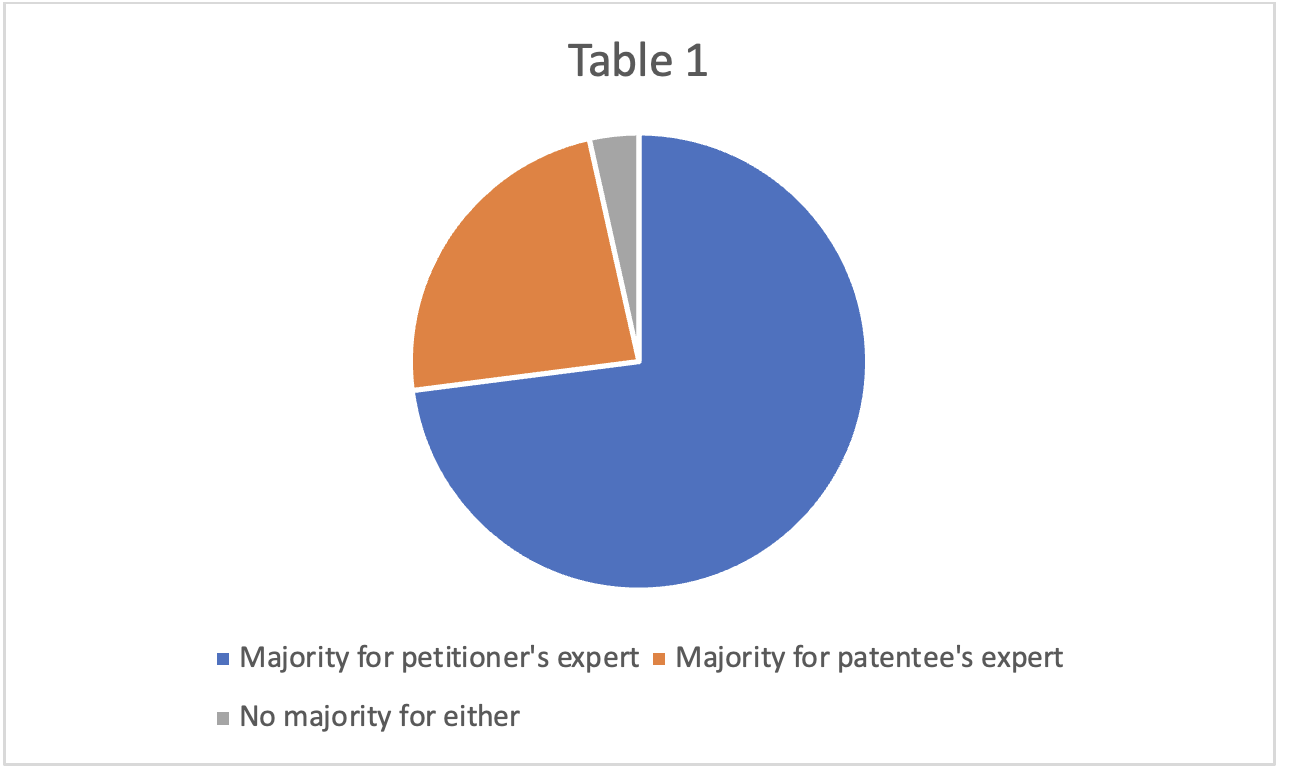

I first looked at the rate at which PTAB panels sided with the petitioner’s expert on contested issues rather than the patentee’s expert. Experts often dispute more than one issue, so I was able to evaluate whether PTAB panels sided with one side’s expert on the majority of the issues for each case. I found that PTAB panels sided with the petitioners’ experts on the majority of disputed issues in a particular case in 124 of those 170 cases, or 72.9% of the time. They sided with the patent owner’s expert on the majority of issues 40 times, or 23.5%. Neither expert won a majority just six times, or 3.5%.

This data shows that the PTAB is almost three times more likely to side with a petitioner’s expert on the majority of issues in a case than with the patentee’s expert.

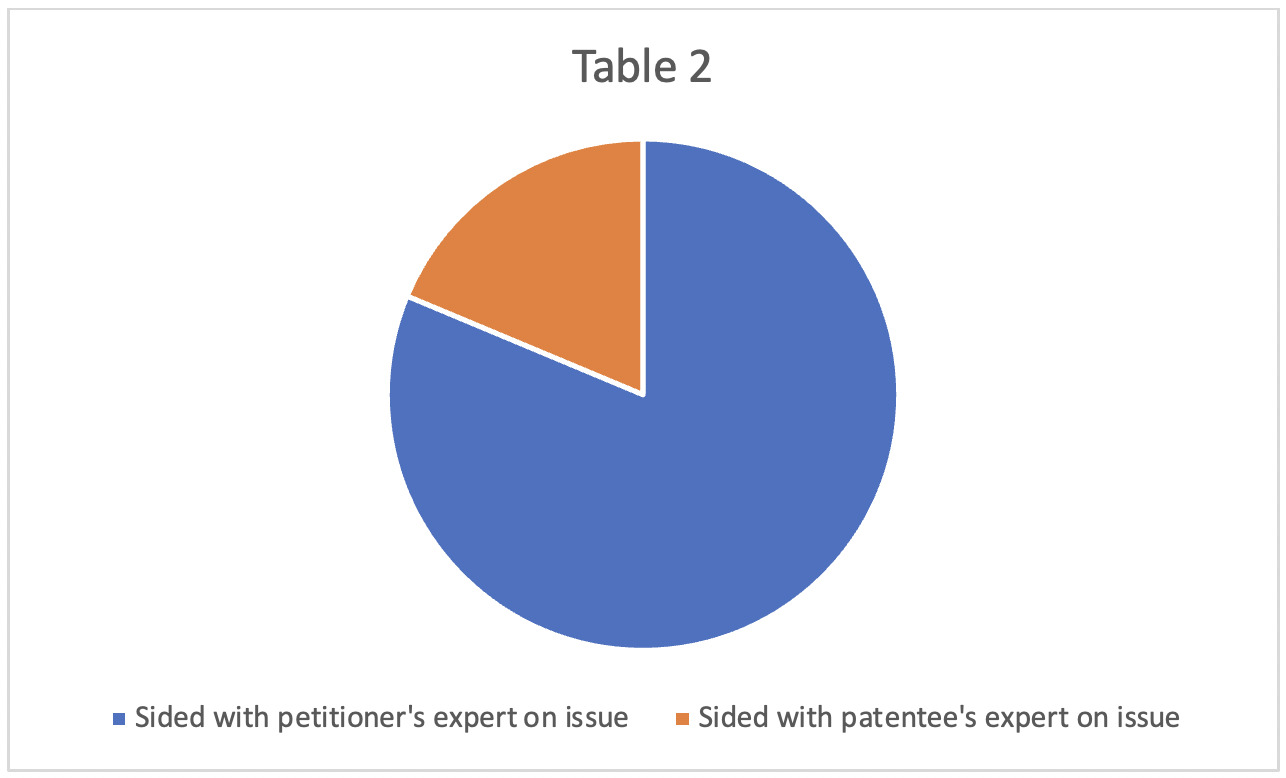

Another way to look at the data is to evaluate how the PTAB ruled on an issue-by-issue basis rather than to examine each case as a distinct entity. I compared the number of times PTAB panels sided with the petitioner’s expert rather than the owner’s expert on an issue across all cases. Across these 170 cases there were 552 issues that experts disputed. My analysis showed that on any particular issue, the PTAB will side with the petitioner’s expert 81.3% of the time, and with the patent owner’s expert just 18.7% of the time.

While these results should concern patent owners, they do not necessarily represent bias. One possible explanation for these imbalances is that most patents in the IPR process are objectively weak, so patentee experts are more likely to lose. But there was no way to objectively determine the strength of the patents being adjudicated in these IPRs.

One way to look at this data that may illuminate potential bias is comparing how often PTAB panels rule in favor of the petitioner’s expert on 100% of the disputed issues with how often those panels rule in favor of the patentee’s expert on 100% of the issues. It seems reasonable to assume that a biased factfinder would take less care in cases likely to result in an outcome consistent with its bias than in cases that appeared to run contrary to that bias. And taking less care would mean favoring the likely winner on each issue without the kind of careful consideration that might lead to a contrary outcome on a particular issue.

PTAB panels sided with the petitioner’s expert on every issue in 107 of the 124 cases, or 86.2%, where they favored the petitioner’s expert overall. Panels sided with patent-owner experts on every disputed issue in 33 of the 40 cases, or 82.5%, where they favored the owner’s expert overall.

These percentages show that when the PTAB sides with the petitioner, it is more likely to follow the petitioner’s expert on every disputed issue than it is to follow the patent-owner’s expert on every issue, even when it favors the owner’s expert overall. The difference is not great. But if one accepts the assumption about biased factfinders ruling in favor of their biases 100% more frequently than against their biases 100% of the time, this evidence does weigh in favor of some bias.

I also tried a different methodology to evaluate possible bias by looking at how frequently PTAB panels present the exact verbatim language from one side’s briefing as the panel’s own conclusion. PTAB panels generally structure their decisions the same way. On each issue, the decision sets forth each side’s position. Then, the panel will state its conclusion on that issue.

A panel adopting verbatim language from one side’s brief as the panel’s own conclusion suggests a lack of care in writing the opinion, which may also indicate a lack of care in evaluating each side’s argument. Bias allows people to make determinations without carefully and independently analyzing an issue solely on its merits.

I looked at the portions of PTAB decisions where the PTAB panel was announcing its conclusion on a particular issue or element, not portions of the decisions where the PTAB panel is merely reciting what each side wrote in its briefs. Merely quoting or copying portions of briefs in laying out each side’s arguments does not seem likely to indicate bias. (Even if it did, however, my analysis also revealed an imbalance favoring quoting/copying petitioner briefs as opposed to patent-owner briefs.) Draft-comparison software highlighted where text in those sections of the PTAB decisions adopted portions of one side’s briefing verbatim as the PTAB’s decision on a particular issue. I only looked at instances where entire sentences, not mere phrases, were identical between a brief and the decision.

That analysis revealed two types of verbatim adoption, quoting and copying. PTAB panels sometimes adopt portions of one side’s brief as their conclusion by acknowledging the quote with quotation marks and a citation. Less frequently, PTAB panels actually copy sentences from one side’s brief without quotation marks or attribution. I’ll refer to these two types of adoption as “quoting” and “copying,” respectively.

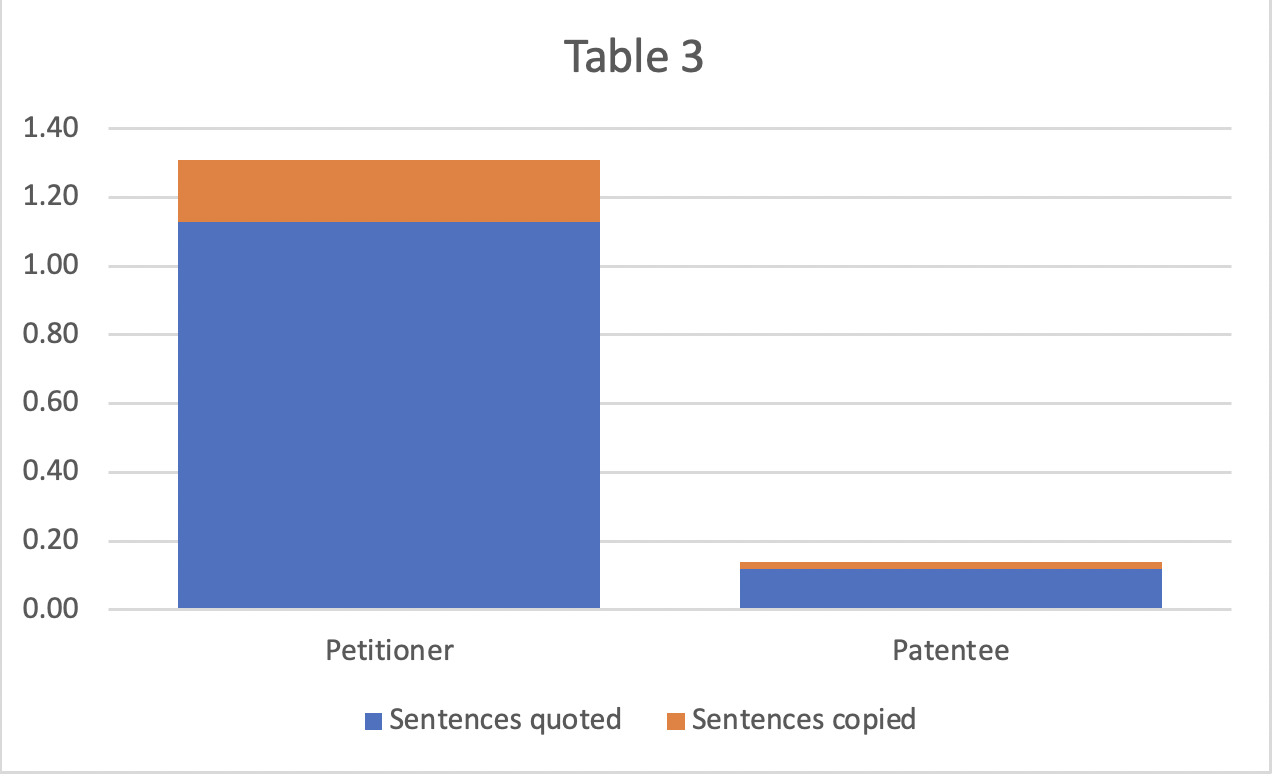

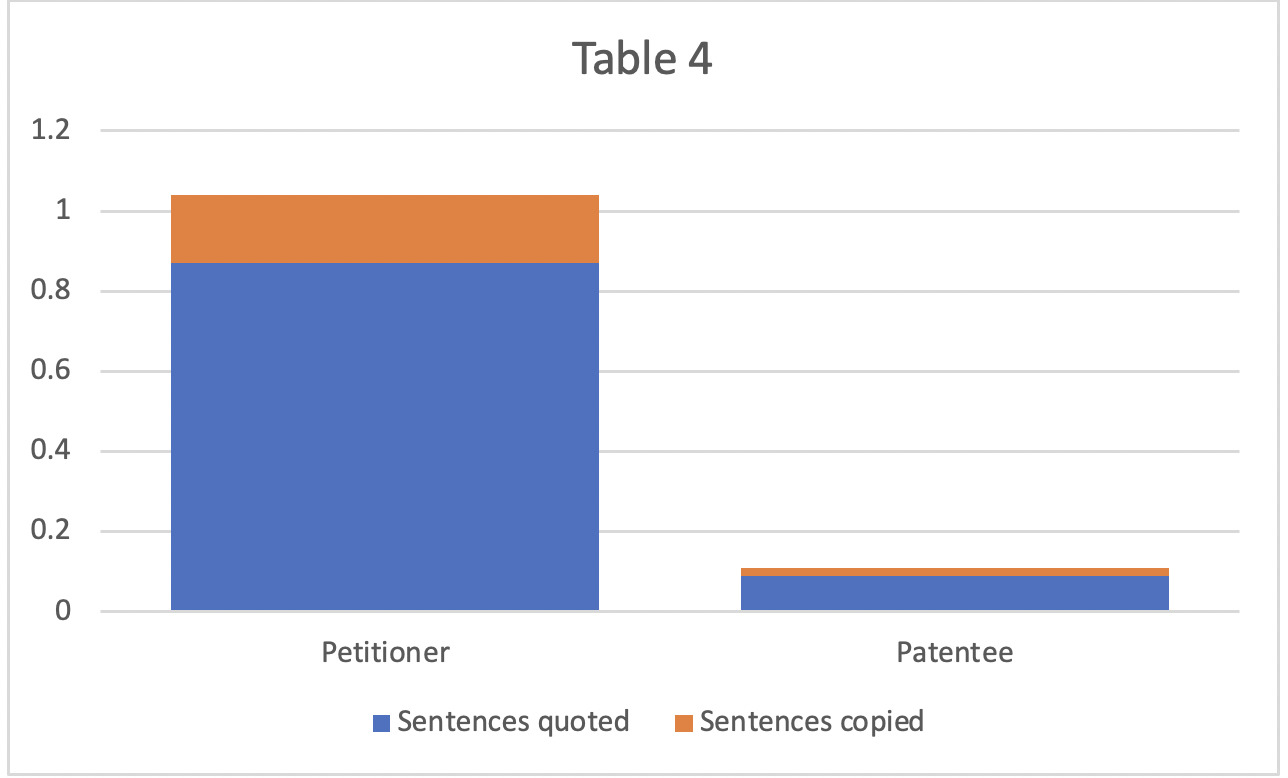

My analysis reveals that the PTAB was more likely to uncritically adopt portions of petitioner briefs verbatim than patent owner briefs. Start with the 170 decisions involving dueling experts for the reasons given above. In those decisions, PTAB panels quoted and adopted an average 1.13 verbatim sentences from petitioner briefs as the PTAB’s conclusion. PTAB panels also copied an average 0.18 sentences verbatim from petitioner briefs without attribution. On the other hand, the PTAB quoted an average of just 0.12 sentences and copied an average of just 0.02 sentences of owner briefs. In other words, PTAB panels were about ten times more likely to adopt as their conclusions verbatim sentences from a petitioner’s brief than a patent-owner’s brief:

There is a potential explanation other than bias for this imbalance. Because a patent owner only needs to show the absence of one claim element in the prior art to avoid invalidity, and because some claim elements are so basic as to be present in almost all the relevant art, patent owners sometimes do not dispute all issues. Quoting petitioner briefs on issues that the patent owner did not dispute suggests time-saving, not bias.

When I limited my analysis to PTAB conclusions on contested issues, however, the pro-petitioner imbalance remained. PTAB panels quoted an average of 0.87 sentences and copied an average of 0.17 sentences from petitioner briefs on contested issues. On the other hand, PTAB panels only quoted an average of 0.09 sentences and copied only an average of 0.02 sentences from patent-owner briefs in resolving contested issues. These numbers are lower than they were when I did not limit my analysis to PTAB judgments on contested issues, but that makes sense; the prior numbers covered more text in the decisions. But despite the numbers being lower, the same imbalance remained. PTAB panels were 9-10 times more likely to quote and copy the petitioners.

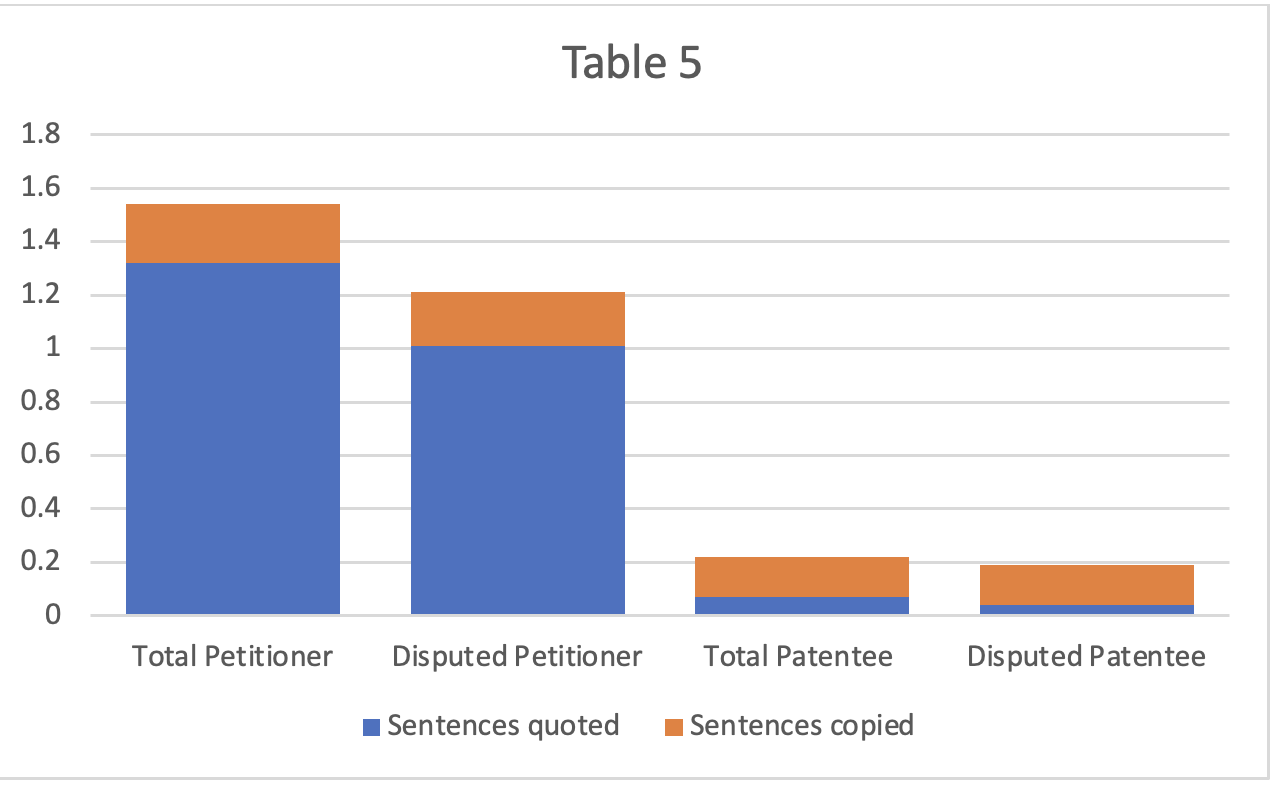

Another way to look at the same data is to compare the quoting and copying in cases where one side achieved complete victory, either the petitioner invalidating every challenged claim, or the patent owner maintaining every challenged claim. These cases, like those where the PTAB sided with one side’s expert 100% of the time, may be the most likely to exhibit bias.

PTAB panels invalidated all challenged claims in 142 of the 170 dueling-expert cases. In those decisions, PTAB panels adopted an average of 1.32 quoted sentences and copied an average of 0.22 sentences from petitioner briefs as their own conclusions. If one only considers parts of the decisions resolving disputed issues, those two numbers drop slightly to become 1.01 and 0.20 sentences respectively, on average.

In the 28 cases where no claims were invalidated, the PTAB adopted an average of only 0.07 quoted sentences and an average of 0.15 copied sentences from patent-owner briefs. Limiting the analysis to contested issues changes the numbers only minimally, to 0.04 quoted sentences and 0.15 copied sentences. This additional analysis comparing the complete-victory scenarios for each side also shows an imbalance favoring the petitioner.

It is true that these averages in both cases are low, so some caution is warranted. Many decisions lack both copying and quoting. What that fact means, however, is that where adoption by quoting and copying occurred, its imbalance in favor of petitioners was more pronounced. For example, one PTAB panel copied nine different petitioner sentences in a decision, and another quoted thirteen petitioner sentences. On the other hand, the most a PTAB panel ever copied from an owner brief was four sentences, and PTAB panels never quoted more than a single sentence from owner briefs.

At the Very Least, There is Reason for Concern

These analyses will likely reinforce patentee concerns about the IPR process. Some caution is warranted, as they are not conclusive. And even if there is systemic pro-petitioner bias in the IPR process, it does not mean that all or even a majority of PTAB judges are subject to that bias. But if IPRs, which now play such an important role in the U.S. patent ecosystem, are flawed in this way, the concerns of the patentee community should be shared more broadly.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 216455222

Author: artursz

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

18 comments so far.

Anonymous

February 23, 2023 12:04 pmInventors are playing small ball. It is time for legislation to change the definition of obviousness itself. A reasonable search by a reasonable POSITA with a reasonable amount of time and money should suffice for patentability, not this fictitious POSITA who has perfect knowledge and unlimited time and money to use AI tools to search all databases in the world to find every reference possible, not stopping until he finds some combination of references to allow an efficient infringer to try to invalidate. There is no reason this fiction must exist. It is scandalous that validity is challenged in EVERY patent case.

The ”limited time” of a patent’s term mitigates the risk of a “wrongly” issued patent. A patent right that never truly vests is no “exclusive right” at all. The distance between claims and the prior art ought to be a damages question, not one relating to validity. The more pioneering an invention, the higher the damages, and vice versa. Or, reduce patent term to 15 years, except upon a showing by the applicant that the claims are so far from prior art that a full 20 year term may be warranted. There’s your “gold plated” patent, reflected in a full 20-year term due to its pioneering nature. Everyone else gets 15 years and vested validity.

We’re all looking at the problem of PTAB bias incorrectly, in my view. Fix the fictional obviousness standard, let patents vest when issued, and let the rest be a damages issue, then there’s no need for IPRs at the PTAB.

Pro Say

February 21, 2023 08:40 pmA curious correlation . . . or mere coincidence?

Why is it that since the advent of the PTAB . . . the kangaroo exhibits at American zoos are only ever half full?

Inquiring minds want to know.

Curious

February 21, 2023 04:54 pmI think that PTAB panels generally have a greater degree of technical expertise and are more comfortable with digging into the details of the technology, than CAFC judges.

Meh. Technology expertise is overrated. The vast, vast majority of the time, the APJ or CAFC judge/clerk is going to be dealing with technology they haven’t seen before. Then, the salient question is are they willing to spend the time to learn that technology so as to determine who is trying to BS the court and who is telling the truth.

Lab Jedor

February 21, 2023 01:24 pmThe USPTO suffers from inaccuracies in determining obviousness, which is the main reason for invalidation in IPRs I believe. If you have to dig that deep and make such, (in my opinion) convoluted arguments as during these reviews, I would say that an invention most likely is not obvious. And that a PHOSITA when presented with the cited material would not create the same or even a similar invention.

The outcome of something being “obvious” is to a large extent arbitrary and depends om how much “deciders” let themselves being guided. The article shows that in the PTAB the “deciders” demonstrate a bias towards the petitioner. That is a reason for concern.

So far we have been unable to objectively test obviousness. New AI Chat applications will/may make it possible to apply “obviousness rules.” I predict that in that case over 50% of claims that are now being rejected or invalidated as being obvious will survive.

Obviousness is not what is possible, it is what is probable. So, if a Patent Chat AI comes up with inventions based on prior art that for instance in its top three possibilities do not contain the claimed invention, then the invention is improbable and not obvious.

Some of my own inventions are highly improbable. I am always puzzled why an Examiner even tries to make it obvious. The reasoning of rejection is often bad and clearly biased towards the desired result of obviousness. I know I have to live with it. I know the Examiner has to go through the motions. But it makes the entire Examination process lack credibility.

Yes Patent Investor. Sarcasm, but only partially so. It would be an opportunity for Mr. Issa showing to be interested in at least investigating bias against inventors. But I am not holding my breath.

David Lewis

February 21, 2023 01:23 pmAlthough is well written and shows that the PTAB is likely biased, regarding the statement,

“And the Federal Circuit has at least as much patent expertise as PTAB administrative patent judges.”

I think that PTAB panels generally have a greater degree of technical expertise and are more comfortable with digging into the details of the technology, than CAFC judges.

Regarding the issue of bias, note that 42.108(c) requires,

“Inter partes review shall not be instituted unless the Board decides that the information presented in the petition demonstrates that there is a reasonable likelihood that at least one of the claims challenged in the petition is unpatentable.” That would seem to mean that once the IPR is instituted, the PTAB necessarily is already biased against, the patentability of “at least one claim.” That said, it is my understanding that there is also a bias toward instituting IPRs and that the system in which the PTAB judges operate creates incentives (perhaps inadvertently) for instituting IPRs.

Alan

February 21, 2023 11:23 amIt would be interesting to see similar data over multiple years. I think early on the bias was even more pronounced. I have had personal experience with this. Worse yet, the “expert” was not a PHOSITA in the art of the disclosed and claimed subject matter. He was an expert’s expert when it came to testifying in patent litigation, but he was anything but an expert in the art. Combine that with 3 APJs who were also not PHOSITAs in the art (nor remotely close) and you have a huge problem.

Paul F. Morgan

February 21, 2023 11:08 amThanks for this statistical comparison of IPRs won or lost where both parties [as usual] filed expert declarations. However, there is a major statistical flaw if you have excluded all of the substantial percentage of IPRs that were denied institution in spite of the petitioners expert declarations [which must be filed with the petition]. Those are all effectively summary judgements for that same patent owner for all but estoppel purposes.

Steven Moore

February 21, 2023 10:48 amExcellent analysis

Patent Investor

February 21, 2023 10:04 amLab Jedor,

“newly installed IP Subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee of the House under the new and improved chairmanship of Darrell Issa.”

I assume this statement was fully tongue in check?

Max Drei

February 21, 2023 08:28 amThree thoughts, from one who has represented applicants and opponents at the EPO for 40 years.

Examination prior to issue is ex Parte. The PTO hears only one side of the argument. Inter Partes post-issue proceedings are the first chance the PTO gets, to hear the other side of the patentability argument. Compare the EPO; currently, only about 15% of oppositions end with the patent maintained as granted.

The EPO is a civil law jurisdiction in which the Examiner, and then the opposition division, assumes the knowledge and the role of the PHOSITA. At the USPTO, the PTO Examiner is not as well-placed to challenge the blandishments of the lawyer representing the Applicant.

At least at the EPO, to oppose and fail is to strengthen the presumption of validity. Caveat emptor then: oppose only when you have good reason to suppose that you will succeed.

No wonder then, that the representations of an IPR petitioner find such purchase. I’m not surprised or alarmed at all by these statistics.

EP Attorney

February 21, 2023 07:58 amInteresting read. Even if US- and EP-patent law on third party review proceedings are not completely comparable, it may be helpful to compare the outcome of the PTAB to the outcome of the corresponding EP-opposition cases if available. As you know the EPO is known to be quite patent owner friendly (only 26% of opposed patents were rejected on 2021) and expert opinions do not play such a decisive role. Such a comparison may add another layer of data to your analysis regarding a possible PTAB-bias.

Curious

February 20, 2023 07:13 pm@Curious, I propose to modify your rubric from the PTAB assumes the Examiner is correct to the PTAB assumes the inventor is wrong. Pre-grant or post-grant PTAB has an extreme bias against inventors.

Legally, the way I put it is accurate. The Board places the burden on the applicant to prove the Examiner is wrong because they are presuming the Examiner is correct. Properly, they should be weighing the evidence/arguments presented by both sides and deciding accordingly.

That minor point aside, your observation is correct, the Board is on the side of “no patent for you” — to paraphrase a famous Seinfeld episode.

Josh Malone

February 20, 2023 06:45 pm@Curious, I propose to modify your rubric from the PTAB assumes the Examiner is correct to the PTAB assumes the inventor is wrong. Pre-grant or post-grant PTAB has an extreme bias against inventors.

Curious

February 20, 2023 06:13 pmComing at this from the ex parte side (and many APJs handle both ex parte appeals and IPRs), I have found that the PTAB’s default position is to assume the Examiner is correct. Moreover, not only will the PTAB assume that the Examiner is correct, they’ll bend over backwards to prop up weak arguments.

20 years ago the BPAI (i.e., the PTAB’s predecessor) was a far more neutral body than it is today. Perhaps it was the Dudas ‘reign of terror’ that changed things — I forgot, it was that long ago — but things definitely changed over time.

The PTAB is a cesspool — at least that’s my opinion.

Scott McKeown

February 20, 2023 06:01 pmCases where the PTAB has agreed with the Patent Owner have already been filtered out at institution. As such, analysis of final results are naturally skewed toward Petitioners.

Lab Jedor

February 20, 2023 04:38 pmThis is great work. Evidence based analysis. We all know that data can be massaged. However different approaches and interpretations are applied all leading to the same conclusion of bias in favor of IPR petitioners.

A real concern is that the PTAB appears to be unable to arrive at an independent conclusion based on its own knowledge and skill in the subject matter and prefers to be guided by petitioners. It confirms what we all have suspected for a long time.

It reminds me of the performance of Chat GPT, which is great at for instance generating Python and C code. But makes verifiable factual errors based on how questions are asked. At least Chat GPT apologizes for errors. Which we should not expect from the PTAB.

The USPTO may/will probably ignore this analysis. However, this article makes a solid and well founded analysis of PTAB bias that favors IPR petitioners.

I would say it is way beyond “time for the PTAB to undergo some sort of unconscious bias training.”

At least a written reply by the USPTO is in order. And if no reply or an unsatisfactory replay by the USPTO is published, this seems to be a good case to be picked up by the newly installed IP Subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee of the House under the new and improved chairmanship of Darrell Issa.

Julie Burke

February 20, 2023 03:00 pmImpressed with your innovative, painstaking approach, Graham, to delve into this complex situation head-on with careful analysis, qualifying caveats and cautionary conclusions.

As a former USPTO insider, I definitely get a whiff of something going on at the PTAB.

Perceptions matter.

Out of an abundance of caution, perhaps it’s time for the PTAB to undergo some sort of unconscious bias training?

Josh Malone

February 20, 2023 12:34 pmFinal Written Decision: Inventors are persuaded by a preponderance of evidence that the PTAB is rigged.