“Under the letter of the law it does not seem inherently wrong to hold at the pleading stage that paid endorsers are potentially liable under trademark law for the words they choose to say to consumers on behalf of would-be infringers, particularly when the endorsers actively facilitate consumers’ purchase of a product.”

When an influencer is paid to promote a brand – and the brand’s name is trademark-infringing – can the influencer be on the hook for the infringement? A federal district court just said yes. The result could widely expand trademark litigation against influencers – and could reshape how companies and their influencers relate to one another contractually.

What Happened?

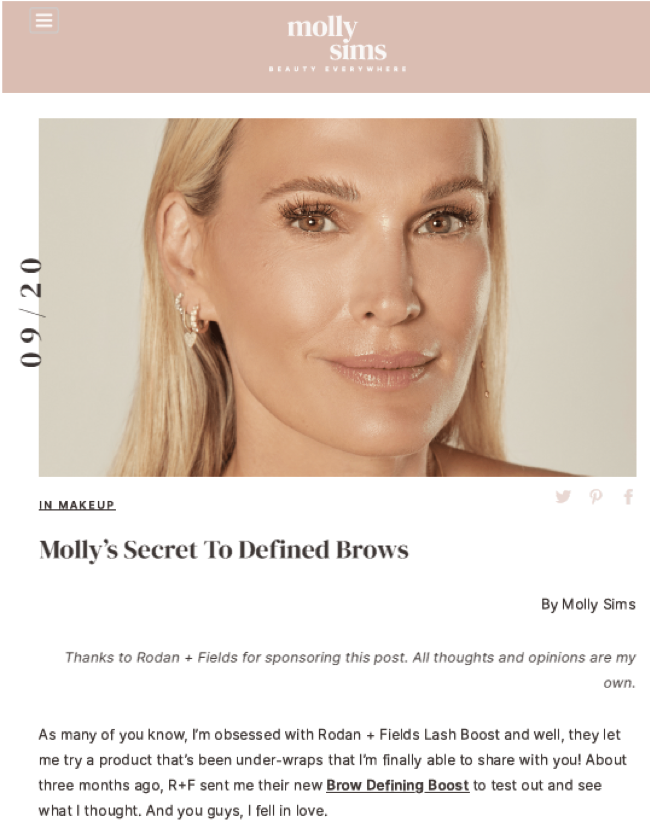

Beauty company Rodan & Fields paid supermodel Molly Sims to blog about its “Brow Defining Boost” product. She so blogged, on mollysims.com:

Competitor Petunia owns the registered trademark BROW BOOST, which it uses in connection with the sale of its “Billion Dollar Brows” eyebrow primer and container. Petunia sued both Rodan & Fields and Sims in Los Angeles federal court. Petunia claimed Sims was liable for the alleged infringement because her blog post had mentioned Brow Defining Boost by name – the argument being that the three-word product name infringes the two-word BROW BOOST.

Petunia asserted claims for direct and contributory federal trademark infringement, and federal unfair competition (false designation of origin). It also asserted California state-law causes of action for false advertising and for alleged unlawful and unfair business practices under Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17200, et seq. Sims moved to dismiss all causes of action against her for failure to state a claim.

The Ruling

On August 6, U.S. District Judge Cormac Carney ruled largely against Sims, refusing to dismiss the direct trademark infringement claim and the unfair competition claim. He held that Petunia sufficiently alleged the blog post was a commercial use of its trademark that could cause consumer confusion.

Significantly, Judge Carney noted that within the post Sims had thanked Rodan & Fields for “sponsoring” it. She also included a photo of the product and linked to a site where the product could be purchased (even informing her readers of the price). At the motion to dismiss stage, the court said, these were clear indications that the blog post could be considered a paid advertisement; it was premature at best to say that the post was First Amendment-protected commentary on a product.

The court likewise noted that this case fit within the general rule that trademark cases ordinarily survive motions to dismiss on the issue of likelihood of confusion, because that inquiry is so fact-specific. Judge Carney held that the facts pled here were sufficient to survive such a motion. For example, the marks at issue were quite similar – plaintiff’s “Brow Boost” vs. defendant’s “Brow Defining Boost.” The one-word differentiator in the middle was not enough as a matter of law to protect the challenged use. The state-law cause of action for unfair business practices likewise was deemed “substantially congruent to claims under the Lanham Act” and as such also survived Sims’ motion.

Sims did score a partial win: Noting a lack of allegations that Sims had actual or constructive knowledge that “Brow Defining Boost” was infringing, Judge Carney dismissed the claims against her for contributory trademark infringement under federal law and for state-law false advertising.

Did the Court Get it Right?

We think so.

At first blush, it may seem odd to hold third-party influencers directly liable for trademark infringement. After all, influencers are not themselves selling competitive products (or any products at all). And, in the corporate context, employees are not typically held personally liable for trademark infringement by their employers unless they are knowingly and actively the moving, conscious forces responsible for the infringement. See, e.g. Chanel, Inc. v. Italian Activewear of Fla., Inc., 931 F.2d 1472, 1477 (11th Cir. 1991); Bambu Sales, Inc. v. Sultana Crackers, Inc., 683 F. Supp. 899 (E.D.N.Y. 1988); cf. Steven Madden, Ltd. v. Jasmin Larian, LLC, 2019 WL 294767, *4 (S.D. N.Y. 2019) (no personal liability for company’s “Creative and Design Chief” given lack of allegations that the individual personally authorized or approved the alleged infringing activities of the corporation).

But Judge Carney’s carefully reasoned 13-page decision nonetheless strikes us as correct:

- Since at least 2009, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has made both celebrity and mom-and-pop endorsers aware that they could be held liable for false or deceptive statements made in advertising. Although the FTC guidance relates to false advertising and not to trademark, it nonetheless is a longstanding guidepost to influencers that their words can put them at legal risk.

- The post at issue here plainly was a paid ad (i.e., commercial speech), so any argument for absolute First Amendment protection as commentary (non-commercial speech) therefore seems strained at the pleading stage.

- Confusion is the linchpin of any trademark infringement claim. Here, the case for confusion, at least at the pleading stage, makes good common sense: a directly competitive product, in similar channels of trade, with a closely similar name. Courts have held that other seemingly innocuous social media advertisements – particularly those using hashtags containing a registered trademark when promoting a product – can support trademark liability. See, e.g. Chanel, Inc. v. WGACA, LLC, No. 18-2253, 2018 WL 4440507 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 14, 2018) (use of #WGACACHANEL in digital and social media marketing was not nominative fair use because the close association between WGACA’s brand and products with this hashtag could create confusion in the mind of consumers as to the true nature of the relationship between WGACA and Chanel); Fraternity Collection, LLC v. Fargnoli, 3:13-CV-664-CWR-FKB, 2015 WL 1486375 (S.D. Miss. Mar. 31, 2015) (denying motion to dismiss because social media posts with hashtags containing defendant’s name or product – e.g. #fratcollection and #fraternitycollection – “could, in certain circumstances, deceive consumers.”)

It should be emphasized that this was just a decision on a motion to dismiss. As the case moves forward, Sims may yet prevail on any number of grounds. But under the letter of the law it does not seem inherently wrong to hold at the pleading stage that paid endorsers are potentially liable under trademark law for the words they choose to say to consumers on behalf of would-be infringers, particularly when the endorsers actively facilitate consumers’ purchase of a product.

What Impact Will the Decision Have?

Online influencer advertising is of course huge business these days. Companies are spending vast amounts to have influencers talk about the companies’ products on Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, blogs and similar online platforms. Some of the money is paid to celebrities like Molly Sims and Kim Kardashian. Much is paid to ordinary people, too.

Here are some things to watch for as the impact of the Petunia decision against Molly Sims begins to be felt:

- Whether filing suit against individual influencers for trademark infringement will become common. A measured “yes” to this one. The decision seems certain to embolden trademark plaintiffs. We would expect to see influencers now routinely named as defendants where two conditions are met: the influencer is a celebrity with deep pockets, and the case for confusion is facially strong. There would be little practical reason to bring claims against mom-and-pop influencers. Such claims would not increase the economic value of a plaintiff’s case, in part because they would not bring access to the sort of substantial assets, and insurance policies, that celebrities might have.

- Whether plaintiffs attempt to use this strategy for other media. Time will tell, but another measured “yes” here. This decision appears to countenance a novel theory of liability that has not been tested in other contexts, such as celebrity endorsements in radio, television or print advertisements. Plaintiff’s success here will likely lead to more litigation against celebrities in different contexts, perhaps even leading to a jurisdictional split in how these types of claims are handled.

- Whether, short of litigation, competitors can use the decision to undercut their competitors’ influencer advertising. This too seems likely. Now that influencers are potentially individually liable for trademark infringement, it is possible (if not likely) that competitors will send cease and desist letters straight to influencers (celebrity or otherwise) – threatening claims for infringement if they do not delete posts and/or recant reviews. Many influencers are unsophisticated and likely to be moved by such threats. This could have the effect of removing some or all of a brand’s native advertising influencers, placing the brand at a competitive disadvantage with minimal effort.

- Whether companies will change how they police their influencers. They probably should. Companies have long had an FTC-imposed duty to monitor the posts of their paid influencers. The monitoring has been focused mainly on whether influencers are making good disclosure of their paid status. Companies may now want to add policies and procedures for making sure that influencers are only using competitors’ trademarks in ways that the companies approve.

- Who will indemnify whom? Influencers who learn of the Petunia decision may begin demanding indemnification from the companies that hire them. Celebrity influencers like Molly Sims and Kim Kardashian may have the clout to win those negotiations. It seems unlikely that the average YouTuber or Instagrammer will know to request indemnification, let alone have the leverage to negotiate such protections. Rather, mom-and-pop influencers seem more likely to get stuck with the current “market” standard: a company-friendly form of contract that actually has the influencer indemnifying the company. See, for example, this, this, and this.

This much seems sure: Sims – who is perhaps best known for wearing a $30 million bikini made of diamonds in the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue – is now enjoying a different kind of fame. Time will tell what broader legal and commercial impacts the Petunia decision may have. We will be watching and will aim to report back in this space.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

BP

August 19, 2021 09:50 amThank you for this piece, the pandemic has brought about many instances worthy of FTC action, including inappropriate FDA claims rising to the level of misbranding per CFR, unsurprisingly some together with trademark infringement. The FTC and FDA are overloaded. And, in the “tech” space, many influencers (paid for tech new) sites are offshore, though facilitated by domestic marketing agents that profit from such activities. It’s an ecosystem in need of regulation.