“To date, a direct Jarkesy challenge in the context of an ITC enforcement action has yet to materialize….But the arguments are there, and the constitutional groundwork has been laid.”

Practitioners in the high-stakes world of the International Trade Commission (ITC) are familiar with the formidable power of a Section 337 remedial order. The threat of a cease-and-desist order, backed by civil penalties of up to $100,000 a day or twice the value of imported goods, is a powerful deterrent. For years, the process for enforcing these penalties has been a settled feature of ITC practice. But a recent Supreme Court decision, Jarkesy v. SEC, has introduced a new constitutional question that ITC litigators might want to watch out for.

Practitioners in the high-stakes world of the International Trade Commission (ITC) are familiar with the formidable power of a Section 337 remedial order. The threat of a cease-and-desist order, backed by civil penalties of up to $100,000 a day or twice the value of imported goods, is a powerful deterrent. For years, the process for enforcing these penalties has been a settled feature of ITC practice. But a recent Supreme Court decision, Jarkesy v. SEC, has introduced a new constitutional question that ITC litigators might want to watch out for.

The Question

The question is this: Does a respondent facing civil penalties in an ITC enforcement action have a Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial?

For respondents, this poses more than an academic exercise. The Supreme Court’s holding in Jarkesy—that the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) in-house adjudication of civil fraud penalties violated the Seventh Amendment—provides a new arrow in the quiver for challenging the Commission’s enforcement authority. At first blush, the parallel is compelling: an administrative agency, through an internal proceeding, is assessing significant monetary penalties. This feels precisely like the scenario the Supreme Court just addressed.

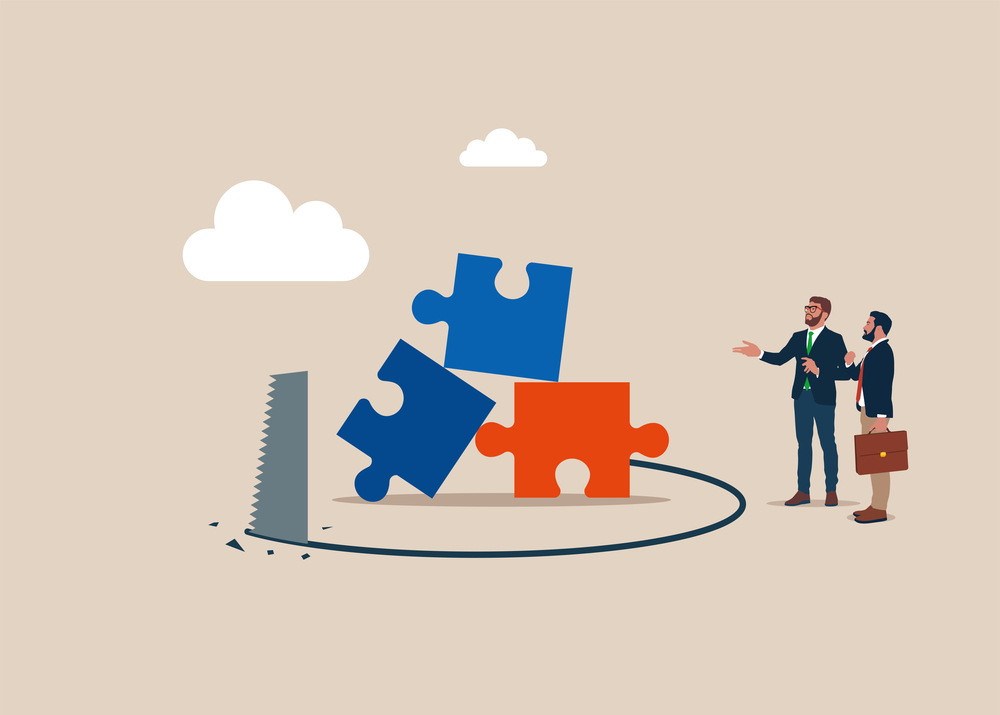

However, as with all things at the ITC, the analysis isn’t that simple. Before we rush to file motions, we must consider the ITC’s powerful counterargument: the public rights doctrine.

The Seventh Amendment’s guarantee of a jury trial for “suits at common law” has long been understood not to apply to disputes involving “public rights”—that is, rights between the government and private individuals. The ITC’s entire mandate is rooted in regulating international trade, a function historically understood as a core sovereign power. As was noted in the Jarkesy opinion itself, proceedings before customs—the ITC’s close cousin in the trade regulation sphere—are a classic example of a public rights matter where a jury trial was never required at common law. The Commission’s argument will be that an enforcement action to protect the U.S. market from unfair trade practices is a quintessential public rights dispute, placing it squarely outside the scope of Jarkesy.

For the vast majority of ITC cases, which are patent-based, this defense becomes even stronger. The Supreme Court’s decision in Oil States Energy Services—the case that upheld the constitutionality of IPR proceedings—explicitly characterized patents not as private property, but as a “public franchise.” If the underlying right being adjudicated is a public right, then an action to enforce an order based on that right is almost certainly a public rights matter as well. For any respondent accused of violating a cease-and-desist order in a patent case, a Jarkesy challenge will be an uphill battle.

Beyond Patents

But what about the ITC’s non-patent jurisdiction? Consider an enforcement action stemming from the misappropriation of trade secrets or the infringement of a common law trademark. These causes of action don’t originate from a government-issued “public franchise” like a patent. They are classic common law claims, pitting one private party against another to remedy a private wrong. An argument could be made that when the ITC adjudicates civil penalties for violating an order in a trade secret case, it is acting in a capacity much closer to that of a common law court. In such a case, a respondent might have a far more compelling argument that the right being adjudicated is private, and thus the assessment of penalties requires the verdict of a jury.

A Tool to Consider

To date, a direct Jarkesy challenge in the context of an ITC enforcement action has yet to materialize. Given that such proceedings are rare, it may be some time before we see a test case. But the arguments are there, and the constitutional groundwork has been laid. While the public rights doctrine will provide a robust shield for the Commission, particularly in patent cases, its defense may be less certain in the context of common law unfair competition claims. For now, it’s a tool for ITC practitioners to keep in their back pocket.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: lightsource

Image ID: 23653377

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Ankar-AI-Nov-20-2025-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Junior-AI-Nov-25-2025-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Juristat-Ad-Firm-Cost-Management-Nov-18-Dec-31-2025-Animated-Varsity-Ad-final.gif)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far. Add my comment.

Anon

November 19, 2025 01:51 pmThis:

“For the vast majority of ITC cases, which are patent-based, this defense becomes even stronger. The Supreme Court’s decision in Oil States Energy Services—the case that upheld the constitutionality of IPR proceedings—explicitly characterized patents not as private property, but as a ‘public franchise.’”

Draws to mind the question of what is a distinction between personal property and private property.

As Greg DeLassus explained in conversations after Oil States, the ‘public franchise’ aspect is still a form of personal property.

Add Comment