The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has admitted to stacking panels of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in order to achieve a desired outcome. While shocking, those in the patent space know this practice is not new. Defenders of the PTAB point to In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526 (Fed. Circ. 1994) as approving of the practice of panel stacking, which it does, at least to some extent.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has admitted to stacking panels of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) in order to achieve a desired outcome. While shocking, those in the patent space know this practice is not new. Defenders of the PTAB point to In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526 (Fed. Circ. 1994) as approving of the practice of panel stacking, which it does, at least to some extent.

Those pointing to Alappat to support modern PTAB panel stacking are, however, grossly misstating the nature of the decision in Alappat, and ignoring the fundamental shift in the adjudicative responsibilities of the Board since passage of the America Invents Act (AIA). Indeed, it is at best misplaced to rely on Alappat for the proposition that expanded panels in contested proceedings have been authorized by the Federal Circuit. At worst, citing Alappat for such a proposition is misleading.

In many regards Alappat was an unfortunate procedural decision, and one made over the very strong and sensible dissent by Judge Mayer, who was joined by Judges Michel, Clevenger and Schall. Still, it is critically important to recognize that the Federal Circuit in Alappat acquiesced to panel stacking in an ex parte appeal brought by patent applicants Kuriappan P. Alappat, Edward E. Averill, and James G. Larsen (collectively Alappat).

If expanded panels ever make sense, they would make the most sense in ex parte appeals where the Office (i.e., Director, or at the time of Alappat the Commissioner) is trying to steer office policy on patent examination, which they have a right to do. The difference now, however, is that since passage of the America Invents Act (AIA) the PTAB has become an adjudicative body that offers an alternative to district court litigation. Predetermination of litigation disputes has never, to my knowledge, been authorized by any court on any level. To the contrary, the American judicial system seeks to provide a fundamental fairness that does not allow any predetermination of the facts. Cf. Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298, 312 (1992)(“Due process centrally concerns the fundamental fairness of governmental activity.”); Carnival Cruise Lines, Inc. v. Shute, 499 U.S. 585, 595 (1991)(forum-selection clauses are judicially reviewable to ensure “fundamental fairness”); Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984)(“the ultimate focus of [an ineffectiveness of counsel] inquiry must be on the fundamental fairness of the proceeding whose result is being challenged.”); Asahi Metal Industry Co. v. Superior Court, 480 U.S. 102, 112 (1987)(exercise of personal jurisdiction requires “fair play and substantial justice”); McDonald v. Mabee, 243 U.S. 90, 91 (1917)(“[G]reat caution should be used not to let fiction deny the fair play that can be secured only by a pretty close adhesion to fact.”).

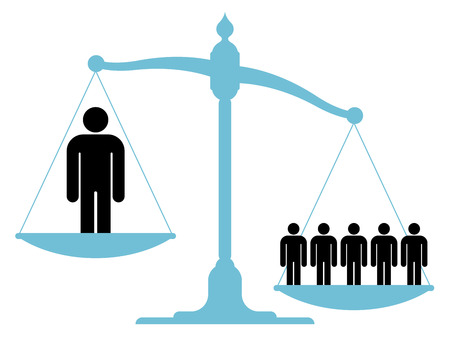

Today the PTAB is using expanded panels, and in some cases phantom expanded panels where those deliberating on the merits are not disclosed to the public or parties, with respect to contests between two or more litigants. This means the PTAB is using expanded panels in order to purposefully reach a predetermined verdict. That is tantamount to picking winners and losers in a predetermined way, which so thoroughly violates American jurisprudential norms of fundamental fairness that it is shocking how anyone could actually support such a practice. Cf. SEC v. Sloan, 436 U.S. 103, 123-24 (1980)(Brennan concurring)(the suspension of trading in a company stock “without notice or hearing so obviously violates fundamentals of due process and fair play that no reasonable individual could suppose that Congress intended to authorize such a thing.”). That is not what an adjudicative body is supposed to do – ever really – but certainly not when there is a contest between two or more parties.

It is still further critically important to distinguish Alappat stacking from current PTAB panel stacking by observing that the Alappat applicants were, in fact, applicants and not patent owners. The Alappat applicants did not possess a patent, but rather were seeking a patent. While that may be of small solace to patent applicants, the truth is a patent applicant does not have a property right, vested or otherwise.

In stark contrast, patent owners that are hauled before the PTAB to defend their already issued patents in either an inter partes review (IPR) proceeding, a post grant review (PGR) proceeding, or a covered business method (CBM) proceeding do have a property right. Furthermore, an issued patent has long been treated as equivalent to a land patent by the Supreme Court, Rubber Co. v. Goodyear, 76 U.S. 788 (1869)(“[T]here is no distinction between… [a patent for land] and one for an invention or discovery.”). Further still, issued patents are specifically vested with all the attributes of personal property by the patent statute. 35 U.S.C. 261. Therefore, a far greater level of process should be required in order to divest a patent owner of their ownership rights. That is, of course, why historically one of the reasons only Article III federal courts were given the authority to divest a patent owner of property rights in an issued patent.

In sum, as deeply troubling as Alappat is in terms of process and procedural fairness, the decision of the Federal Circuit to acquiesce to panel stacking in Alappat absolutely does not mean that panel stacking in contested cases under the AIA has been authorized by the Federal Circuit. Indeed, panel stacking, whether overt and on the record or as the result of secret internal deliberations within the PTAB, has never been authorized by the Federal Circuit relative to IPR, PGR and/or CBM proceedings. At some point whether panel stacking and admitted predetermination of outcomes is allowed in AIA contested cases will be a question of first impression at the Federal Circuit.

Image Source 123rf.com

Image ID: 25433721

Copyright: Adrian Niederhaeuser

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[[Advertisement]]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-1.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

11 comments so far.

PTO-Indentured

March 26, 2018 08:59 pmDavid @7

I stand corrected.

Yes, in view of massive, compounding and still unchecked debt (in the high trillions), and an AIA overturned patent-system apple cart, it is fair to say the U.S. is neither a rich nation, or one likely to soon become enriched by fair-innovation again.

Anon

March 26, 2018 08:44 pmBemused,

I am flattered.

But no, I am merely a humble servant (whose clients, it appears, include the fallen angel).

Bemused

March 26, 2018 06:14 pmDavid Hoyle@4: “Since i am a relatively new visitor to this site, one thing i have already learned. Anon would argue with almighty God himself!”

Wait a sec. I thought Anon was G-d? Or is that Gene and Anon is the Archangel Michael? I get so confused sometimes.

Joachim Martillo

March 26, 2018 05:43 pmIn the hands of a corrupt senior USPTO official, PTAB phantom expanded panels is a tool nonpareil for corruption. See PTAB Phantom Expanded Panels Erode Public Confidence and Essential Fairness.

David Hoyle

March 26, 2018 03:05 pmPTO-Indentured I disagree. The USA is over $20 trillion in debt. That’s not rich.

The only hope it had/has is a strong patent system, many innovative individuals willing to work long hours, and investors willing to take a chance.

The AIA has overturned the apple cart and there is no way the USA will ever work its way out of this overwhelming debt without the AIA being overturned.

PTO-Indentured

March 26, 2018 12:12 pmRE “no rich country who has a poor patent system.”

The U.S. is a rich country and AIA is literally a poor patent system … with apparently no downturn (or combinations thereof) too big to be ignored.

While AIA’s PTAB, meaner-and-not-gentler BRI, and serial (and in some cases seemingly limitless) IPRs, suffice to slaughter nine out of ten U.S. so-called ‘challenged patents’ (where such “challenges” require little more than ‘ante up’ pittance to a Elite Tech Co.), AIA will not ‘make’ the U.S. “a poor country”.

But make no mistake, it has produced a patent system in a nosedive, and AIA IS making the U.S. poorer, by: relegating a mind-boggingly high percentage of U.S. patents defenseless, for years; by driving investment in IP out of the U.S. into those countries who DO defend their IP. Where the winners are multinational corporations not reliant on the fate of, nor needing any loyalty whatsoever to, a U.S.-only patent system in their global IP strategies.

Where so many U.S. patents are rendered worthless, efficient infringement (so much more benign sounding than “patent stealing”) will continue to dominate, and U.S. innovation (and its proven nation-enriching revenues of pre-AIA days) will wane.

If AIA continues, the PTO needs a new ‘truth in advertising’ approach:

Warning to U.S. Independent Inventors

“IMPORTANT! The fees we charge applicants throughout the prosecution of a U.S. patent application and the life of a U.S. patent are directed to patents the PTO issues using a first PTO standard of validity. However do note, since AIA rules were implemented in 2012 such PTO-issued patents are subjected, when challenged, (most often by one or more large entities), to a second PTO standard of validity, so much easier to defeat validity-wise that historically nine out of ten patents — we’ve issued — have been rendered essentially defenseless/worthless. Consequently U.S. independent inventors should expect their patents to be attacked under our second easier-to-defeat standard — not having a validity we first ascribed to them, and proportionate to their perceived value in the U.S. market.”

Anon

March 26, 2018 10:11 amMr. Hoyle,

Maybe that’s where the phrase “the Devil’s Advocate” comes from.

By the way, you may want to check out the famous Sir Thomas Moore scene at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NUqytjlHNIM

David Hoyle

March 26, 2018 09:46 amSince i am a relatively new visitor to this site, one thing i have already learned. Anon would argue with almighty God himself!

“There is no poor country who has a great patent system and no rich country who has a poor patent system.”

Thanks Gene for this article. It cleared up my questions about Alappat.

Anon

March 25, 2018 06:53 pmThe misleading notion is whether ANY such “authorization” is even required.

Until the issue is actually challenged, the court has NO say on ANY such “authorization.”

Gene Quinn

March 25, 2018 04:25 pmAnon-

I have no idea how you can say the title is misleading. The entire article is about how the Federal Circuit has not authorized the panel stacking the PTAB engages in with respect to contested cases. That is literally the entire point of the article.

I know you and I went around on the Taylor Swift article as well. But you do realize that a title is a title and not an entire paragraph, right? You do realize that there is a limit to how long titles can be and still be useful?

Anon

March 25, 2018 01:19 pmI think the title (and the defense) is a bit misleading.

When this issue first came up on these boards, I was one of the very first to point out that the practice was not a new one.

Alappat was referenced, but was not referenced as any type of court-approval.

The slightly off thrust of the practice needing court approval is somewhat interesting – and one that I would (if I were feeling argumentative) classify as a strawman.

I do realize that some (to my not-so-humble sense) less-well-informed posters have attempted to inflate the Alappat case to be something that THAT case simply did not address.

That person was clearly wrong.

But that person being wrong does not mean that the matter is even “up for” a court to decide. I am not aware that any “challenge” has ever been before the courts to decide on whether the prior power to engage in expanded panel making cannot be allowed. Since this has never actually been so asserted, there has never actually been any defense made of the practice.

The practice is as it is.

“ ignoring the fundamental shift in the adjudicative responsibilities of the Board since passage of the America Invents Act (AIA)”

This has nothing to do with the power that the USPTO director has always had. The AIA did nothing in regards to that power.

I would postulate in fact that Congress did not even contemplate this aspect when the AIA was under construction. That is not to say that this lack of recognition does not imbue a certain level of infirmity to the AIA. The AIA is one of the worst written pieces of patent law legislation ever.

I point this out – not in disagreement with the overall thrust of the article (to which I am in agreement with).

I point this out because the infirmity is even more pernicious when it is recognized in the context that Congress did not even bother to understand basic administrative law when it provided the administrative agency of the Executive branch the level of lack of oversight with adjudicatory powers in an agency that ranks among the lowest in internal structure to safeguard separation of power concerns***.

This is NOT a direct “fault” of the USPTO.

This IS a direct fault of Congress.

Putting the problem into the larger context (my view) is what will properly set the table for a “more proper” challenge in the courts as to any type of facial or as applied Constitutional infirmity (against the law as written by Congress).

*** the separation of power concerns are in fact multiplied given how the USPTO “judicial” function has overstepped any sense of comity with the structure of the rest of the government – vis a vis (for example) which branch of the government gets to decide the scope of American Indian Tribal immunity.