Posts Tagged: "standard essential patents"

Last week, IPWatchdog hosted its annual SEP conference, which once again took place in virtual format. I either moderated or directed/produced all the panels, so I stayed busy throughout the week, but still managed to pay attention to what was being said by the panelists. For some panels I participated more, making it a bit more challenging to take notes, so when I say what follows are statements that particularly piqued my interest, I am by no means suggesting there weren’t many more golden nuggets of wisdom imparted to the over 900 registrants over our four-day program.

In this article, we’re going back to basics and discussing why our smartphones work everywhere, doing things closer to science fiction of the 1960s or 70s than anyone would have believed, as well as the role that Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) play in making this happen. We are going to examine inherent conflict between innovators and inventors that create new products and services, patent their inventions, and the implementors that leverage and deploy those inventions. Most of all, we’re going to discuss the process that converts these inventions and patents into money. A lot of money. Millions, tens of millions, and sometimes even billions of dollars. Why? Because your smartphone would be a paperweight without these innovations and patents. And soon vehicles, home appliances, production lines, meters, healthcare devices and many more industries will follow.

Most market experts predict dramatic changes in the auto industry because of shifting consumer preferences, new business models and emerging markets. The sector also looks set to be heavily affected by new sustainability and environmental policy changes, as well as by upcoming regulations on security issues. These forces are predicted to give rise to disruptive technology trends, such as driverless vehicles, electrification and interconnectivity. Forecast studies posit that the smart car of the near future will be constantly exchanging information with its environment. Car-to-X or car-to-car communication systems will enable communication between cars, roadsides and infrastructure, while mechanical elements will soon be embedded into computing systems within the internet infrastructure. The auto industry is one of the first sectors to rely on Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, which connect devices, machines, buildings and other items with electronics, software or sensors. Interconnectivity across multiple vehicle parts and units relies on the specification of technology standards such as 4G or 5G, Wi-Fi, video compression (HEVC/VVC), Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB) and Near Field Communication (NFC) or the wireless charging Qi standard to name a few.

In a previous article, we discussed the difference between a reasonable royalty for patent infringement and a FRAND licensing rate, both in terms of their origins and objectives: the former being a creature of statute and case law that seeks to compensate a patent owner for infringement, whereas the latter is rooted in contract and seeks, amongst other things, to address issues of royalty stacking and discriminatory licensing. Despite these differences, we noted that these two concepts have often been treated interchangeably by courts, often leading to confusing results…. Pursuant to appeal of that decision, however, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has now addressed the photonegative question in HTC Corp. et al. v. Telefonaktiebolaget LM et al., case number 19-40643: are patent laws regarding what constitutes a reasonable royalty applicable to questions of compliance with FRAND-related contractual obligations? Though the majority decision did a great job highlighting the distinction between these two different concepts, there was a concurring decision that continues to blur the line.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit today affirmed an Eastern District of Texas court’s judgment for Ericsson, finding no error in the district court’s jury instructions, declaratory judgment or evidentiary rulings, and rejecting HTC Corporation’s allegations that Ericsson had breached its contractual obligation to offer a license on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. The case stems from HTC’s refusal of a 2016 licensing deal in which Ericsson proposed a rate of $2.50 per 4G device to license its standard essential patents for mobile devices. Although HTC had previously paid Ericsson about $2.50 per device for the patents under a 2014 licensing agreement, in 2016 the company independently assessed the value of Ericsson’s patents and ultimately proposed a rate of $0.10 per device in 2017, which was based on the “smallest salable patent-practicing unit.” According to the Fifth Circuit, Ericsson considered this “so far off of the norm” that negotiations stopped, and a few days later, HTC filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, alleging breach of FRAND terms.

Last week, an article was published on the Social Science Research Network (SSRN) website by Matteo Sabattini, who is the director of IP Policy at Ericsson. SSRN is an open research paper repository that does not peer-review any articles that are uploaded. Sabattini’s new article, a summary of which was also recently published on IPWatchdog, is titled, “When is a portfolio probably standard-essential?” and cites several studies that determined the overall essentiality rate for 4G and 5G. Here, Sabattini cites the Concur IP study that was part of the expert witness report of witness Dr. Zhi Ding in the TCL v. Ericsson litigation case, as well as several studies published by David Edward Cooper from Hillebrand Consulting, who is an Ericsson commissioned subject matter expert and who also testified in court, e.g. for the Unwired Planet v. Huawei case. Finally, Sabattini also mentions the EU commission 2017 study conducted by IPlytics:

Do owners of patents for which licensing declarations have been made enjoy more rights than other patent holders? Do such licensing declarations impose obligations on potential licensees rather than on patent holders? Should prospective licensees have no right to challenge such patents? In another responsive article, that is what one commentator claims our series of articles on IPWatchdog asserted, although we never wrote or suggested anything of the sort. In doing so the commentator employs intentionally misleading language like “declared essential patents” to characterize such licensing declarations as claims of essentiality, and “prov[ing]… licenses are needed” which, as will be explained, is not possible. These hyperbolic assertions are commonplace in the world of standards related patents, as are straw-man arguments concocted by implementers trying to escape the need to take a license. While we appreciate that all of this comes down to innovators wanting to be paid for their innovations embodied in standards and implementers wanting to pay less, or nothing, for using those innovations, we’d prefer the debate to be without histrionics and hyperbole. We hope this final response will clear up any remaining misconceptions.

A recent series of five articles on IPWatchdog address various aspects of licensing cellular standard essential patents (SEPs) on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms by examining statements from entities involved with licensing. The authors also provide their commentary on the statements and cite various authorities that they suggest are consistent or inconsistent with principles advocated in the statements. The articles lean heavily in favor of the positions of a few companies that derive significant revenue from SEP licensing. For this reason, they fail to present a balanced view. Indeed, to read the series, one might conclude that the major priority for SEP licensing should be to extract excessive revenues for SEP patent owners. Quite the contrary, a key priority should be applying FRAND safeguards against outsized, windfall profits resulting from abuse of SEPs to the detriment of innovative companies that engage in research and development and supply products to the marketplace. Those safeguards include applying well-established principles of patent law to SEPs, including when it comes to patent valuation and patent litigation, where a patent holder is rewarded with fair royalties that reflect the incremental value of any infringed and valid SEP.

Standard-essential patents (SEPs) are on the rise as the number of yearly newly declared patents has almost tripled over the past five years; there were 6,457 net new declared patent families in 2015 compared to 17,623 yearly net new declared patent families in 2020 (see figure 1). The 5G standard alone counts over 150,000 declared patents since 2015. Similarly, litigation around SEPs has increased. One of the driving factors of recent patent litigation is, on the one hand, the sharply increasing number of SEP filings, and on the other, the shift from connectivity standards (e.g. 4G/5G, Wi-Fi) mostly incorporated in computers, smart phones, and tablets to new industry applications where standards are implemented in connected vehicles, smart homes, smart factories, smart energy and/or healthcare applications.

As the battle over the adequate forum for Ericsson v. Samsung continues, the question arises as to how the court will eventually deal with the valuation of the standard essential patents (SEPs) at stake. Here, the U.S. courts are at an advantage. After all, the United States has from the outset illustrated global thought leadership on the valuation of SEPs. Historically, courts have accepted two principal methods to determine the value of SEPs: the Comparable Licenses Approach and the Top Down Approach. These methods have come to be seen as compatible with the Georgia Pacific Criteria, which set out the core valuation principles in the United States and, increasingly so, even beyond U.S. borders.

Much has been said about how 5G will better use the airwaves, giving wings to new communications between people and between devices. Little has been said though about how 5G could change markets and industries. The equipment market for the radio access network (RAN) is a good example of just one market that is now caught in the updraft of such change. Another market bound to rise is the market for patent licensing—and, in particular, standard essential patent licensing for 5G RAN. To help make sense of the 5G patent licensing market, we have developed an AI-based 5G landscaping tool to help identify and weigh the relative patent portfolios (OPAL) and an indexed repository of all technical contributions made to 3GPP 2G-5G standardization work (OPEN).

Standard Essential Patents (SEPs), as the name suggests, are an essential set of patents used for the implementation of a standardized technology. This set of patents renders it impossible to implement or operate standard-compliant equipment without infringement. Does that mean every patent declared by any company is essential? In a word, no. This article intends to address this aspect in detail and pave way for licensees to save costs and pay for what they use in their implementations.

In a previous article, we considered the difference between a reasonable royalty for infringement of a U.S. patent and a fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) rate for licensing standards essential patents (SEPs). Among other points, the article discussed the then ongoing case between Optis Wireless Technology, LLC et al. v. Apple Inc., Civil Action No. 2:19-cv-00066-JRG (E.D. Texas, September 10, 2020). Most recently, Judge Rodney Gilstrap issued an Opinion and Order as to Bench Trial Together with Supporting Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (“Opinion and Order”) and ordered Final Judgment be entered. This Opinion and Order sheds a little more light on the issue of damages for SEPs, including the role of exemplary damages for willful infringement, but also leaves some key questions unanswered.

A close examination of SEP databases reveals that a large number of patents that have been declared SEPs are not essential…. Patent owners are obliged to declare the patent as essential even if they are doubtful about its essentiality. Unfortunately, a few patent owners may intentionally proclaim many of their patents to be essential to gain benefits or a business advantage. In practice, there are multiple reasons potentially essential patents and patent applications might be rendered non-essential. For example, a patent could be granted with amendments that cause it to be no longer essential. Whenever implementers bargain for the licensing fees, they must examine whether certain patents are actually essential, which can stall negotiations and lead to litigation.

In a major 2018 speech, Justice Department Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust Makan Delrahim enunciated a “New Madison Approach” (NMA) (a tribute to James Madison’s support for a strong patent system) designed to restore greater respect for efficiency-seeking patent transactions in antitrust enforcement (a 2020 law journal commentary discusses the NMA and the reactions it has elicited, both positive and negative). Consistent with the NMA, the Trump Administration Antitrust Division took a number of initiatives aimed at reducing perceived new antitrust risks associated with widely employed patent licensing practices (particularly those touching on standardization). Those new risks stemmed from Obama Administration pronouncements that seemed to denigrate patent rights, in the eyes of patent system proponents (see here, for example). Given this history, the fate (at least in the short term) of the NMA appears at best uncertain, as the new Biden Administration reevaluates the merits of specific Trump policies. Thus, a review of the NMA and the specific U.S. policy changes it engendered is especially timely. Those changes, seen broadly, began a process that accorded greater freedom to patent holders to obtain appropriate returns to their innovations through efficient licensing practices – practices that tend to promote the dissemination of new and improved technologies throughout the economy and concomitant economic welfare enhancement.

Latest IPW Posts

Tips for Using AI Tools After the USPTO’s Recent Guidance for Practitioners

May 2, 2024 @ 08:15 amUSPTO Proposes National Strategy to Incentivize Inclusive Innovation

May 1, 2024 @ 02:15 pmThe SEP Couch: Shogo Matsunaga on SEPs and the Law in Japan

May 1, 2024 @ 07:15 amWitnesses Tell Senate IP Subcommittee They Must Get NO FAKES Act Right

April 30, 2024 @ 05:15 pm

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

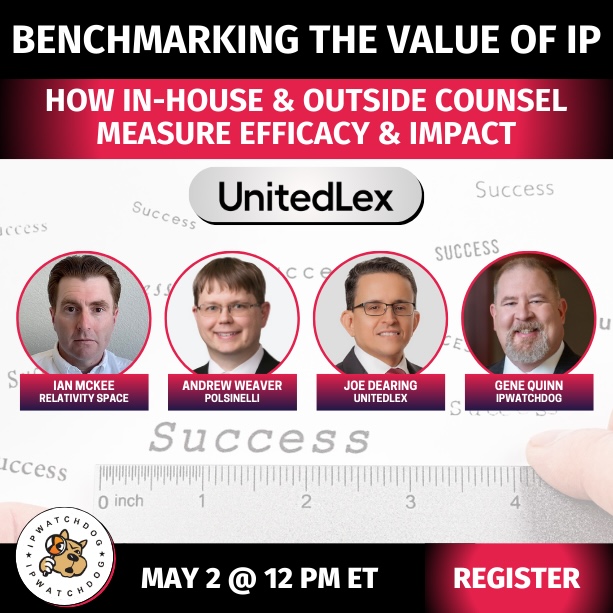

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)