“If a copyrightable work is used as the starting point for a finished work that will contain generative material, that may open a loophole…to ensuring copyright protection over subsequent exploitations of the finished work, and the portions of the work that may not be entirely human creation.”

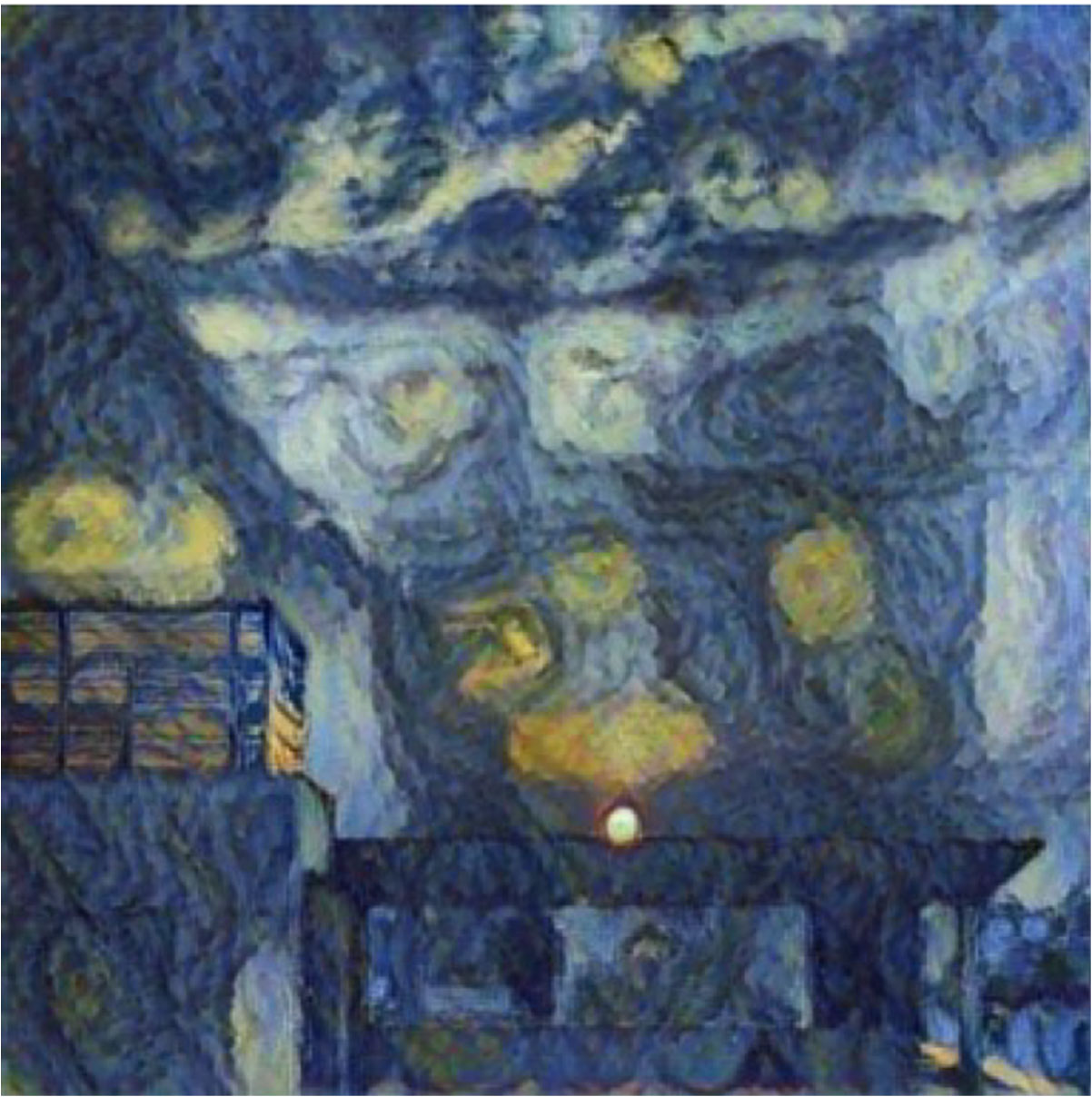

SURYAST – Source: U.S. Copyright Office letter

On December 11, the Review Board of the U.S. Copyright Office (USCO) released a letter affirming the USCO’s refusal to register a work created with the use of artificial intelligence (AI) software. The decision to affirm the refusal marks the fourth time a registrant has been documented as being denied the ability to obtain a copyright registration over the output of an AI system following requests for reconsideration.

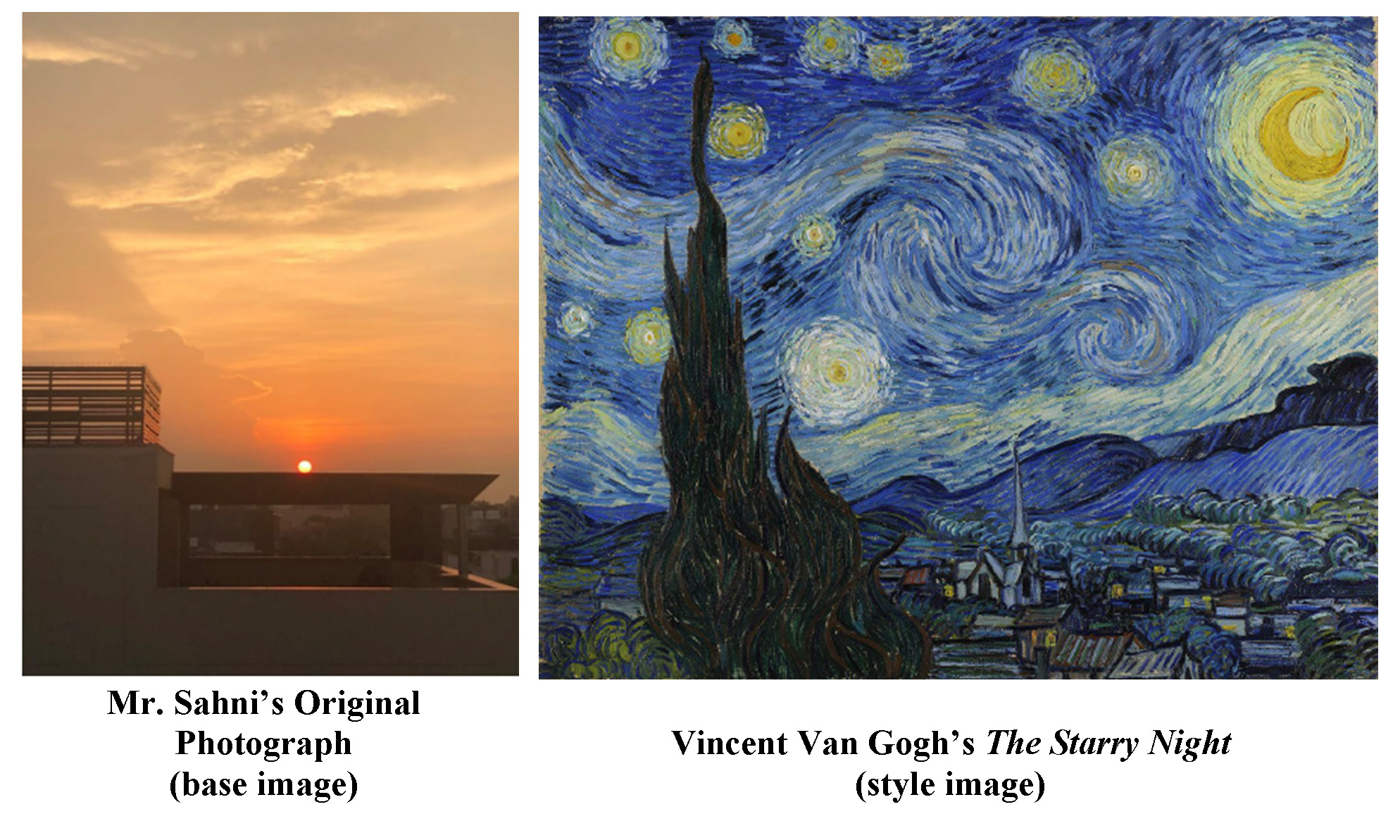

The work in question is a two-dimensional computer-generated image titled “SURYAST” that was created by Ankit Sahni, in part, using a custom-developed software program named RAGHAV. The USCO’s analysis focuses on issues such as lack of human control, contradictory descriptions of the tool (such as whether it is a filter or a more robust generative tool), and whether the expressive elements of the work were human authored.

Meet RAGHAV

Sahni submitted an application to register the work in December 2021 and listed himself and the AI painting app as the two authors. More specifically, Sahni noted an original photograph as part of his authorship, while the software was listed as solely contributing the “2-D artwork.”

In response to the USCO’s request for additional information, Sahni provided a 17-page supplement explaining the technology and how it was used. He explained the process involved use of his original photograph of a sunset along with an image of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night for the “style” to be copied by the AI tool.

In June 2022, the USCO issued its initial refusal to register the work because of the lack of human authorship, noting the inability to separate the human authorship from “the final work produced by the computer program.” It also noted that the work was a “classic example[] of derivative authorship” because, as the Review Board writes, “it was a digital adaptation of a photograph.”

Source: U.S. Copyright Office letter

In September 2022, Sahni requested a reconsideration. He argued “the human authorship requirement does not and cannot mean a work must be created entirely by a human author.” However, the USCO upheld the initial refusal and denied the first request for reconsideration.

The second request for reconsideration came in July 2023 and presented three arguments. The first argument involved an assertion that RAGHAV’s role was only as an “assistive software tool” with ultimate creative control in the hands of Sahni through the selection of his original starting photograph, the inclusion of The Starry Night, and the additional variables under his control. The second argument focused on the human-authored elements in the work that he sought to register. The third argument sought to attack the classification of the machine-generated work as a derivative work due to its lack of substantial similarity and that the “human author’s total creative input in both the original photograph and the Work should be considered together […]”. For example, Sahni pointed to the way in which a painter might sketch on their canvas or a sculptor assembles clay before reaching a final form.

A large portion of the USCO’s analysis is spent exploring the discrepancies between Sahni’s recounting of the creative process and functionality of his tool. The USCO focuses on the level of control Sahni retained over RAGHAV, noting the description provided in the second request for reconsideration “inaccurately minimizes RAGHAV’s role in the creation of the Work and conflicts with other information in the record.”

After reviewing the provided research, the USCO concludes: “RAGHAV’s interpretation of Mr. Sahni’s photograph in the style of another painting is a function of how the model works and the images on which it was trained on—not specific contributions or instructions received from Mr. Sahni.”

Fourth Time, Not the Charm

In June, the USCO reiterated its focus on the application of the de minimis standard when determining whether or not a work that contains generative material is eligible for copyright protection. The standard, taken from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Feist v. Rural Telephone and solidified as policy in the USCO’s Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, requires that “AI-generated content that is more than de minimis should be explicitly [disclosed and] excluded from the application.” The generative material is not protectable and would be considered public domain.

Beginning in February 2022, the Review Board upheld the USCO’s first documented refusal to register “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” when Dr. Stephen Thaler attempted to register the work originally with the AI software as the author and himself as the claimant. The refusal to register was challenged in federal court as part of a continued effort of Thaler and his supporters to exhaust a multitude of legal theories attacking the human authorship requirement that the USCO identified as well-established. As of August, the district court decided in favor of the USCO and leaves Thaler in pursuant of an appeal to overturn the decision.

The second documented refusal to register a generative AI work came in February, following a series of investigations beginning in the fall of 2022 into a previously granted registration of a graphic novel by Kris Kashtanova. The USCO ultimately decided to partially cancel its previously issued registration due to the “randomly generated noise that evolves into a final image” when using the AI-powered text-to-image generation tool Midjourney. Kashtanova has since decided against pursuing a challenge to the partial cancellation, and now works as a Senior Creative Evangelist in AI at Adobe.

In September, the Review Board upheld the USCO’s third documented refusal to register a generative AI work, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, that became internet famous for winning in the digital arts category at the 2022 Colorado State Fair’s annual fine art competition.

It’s also worth noting that the United States isn’t the first jurisdiction in which Sahni attempted to register the SURYAST work. In 2020, the work was recognized for copyright protection by the copyright office in India when Sahni filed a second application listing himself and the AI software as the authors. The registration later received a withdrawal notice and became subject to an investigation over the use of a machine. Under India’s copyright law, the issue turns on whether or not: (i) AI is capable of meeting the originality requirement, and (ii) the ‘person’, a term that remains undefined in India’s Copyright Act, that is responsible for the computer-generated work (which are recognized under the country’s copyright law) must be a human.

Protecting Partially Generative Derivative Works

An important practical takeaway from this latest development is that the original photograph used as the grounding for a prompt is likely protectable human authorship. Meanwhile, the output of the digital manipulation is not a protectable derivative. This distinction is strategically important for creatives working with generative AI tools.

The USCO has made it clear that generative works are not protectable, and therefore considered public domain. If a copyrightable work is used as the starting point for a finished work that will contain generative material, that may open a loophole (for lack of a better term) to ensuring copyright protection over subsequent exploitations of the finished work, and the portions of the work that may not be entirely human creation.

For example, there may be enough of Sahni’s original photograph contained in the final version of SURYAST to bring claims of infringement if anyone copies, distributes, or otherwise uses the work in an unauthorized manner. It would require Sahni to register the original photograph and meet the other requirements for protection, but theoretically could strengthen any argument against the generative derivative work as being fully in the public domain.

Of course, another key takeaway is that creators should strongly consider having a fully developed legal strategy when communicating with the USCO. This latest letter from the USCO contains critical examples of where changing descriptions of an artistic process, and the tools used, can prove to be detrimental to creators and undermine their attempts to bring clarity as the USCO reviews their application.

Alex Garens of Day Pitney, LLP, is listed as the counsel for Sahni to receive the correspondence with the USCO.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

16 comments so far.

Anon

December 23, 2023 09:04 amAlas, I may have spoken too soon about Just Eric’s following the thread ‘below the fold” of Page 2 and beyond.

Anon

December 19, 2023 04:06 pmJust Eric,

I appreciate your desire to try to ‘carve out’ some “use as a tool” in order to provide a view that artists CAN create something that they can truly call their own ‘work of art,’ and for which, obtain proper copyright protection (and I do appreciate you sticking with this conversation, even as the thread has slipped to ‘page 2’ as of the date of this posting).

We are talking past one another, as I have already provided that such CAN exist (as case law has already shown) when the additional actions are more than merely “that of a helper.”

In this sense, one must be able to view the situation as a human helping another (and that ‘another’ being a non-human).

Just as currently a human helper for another human does not rise to a level of creative input so as to earn that human HELPER a right to claim copyright, so too with those merely ‘cleaning up.’

I also recognize that truly defining (and setting a level of capability ) of what is LOOSELY bandied about as “AI” would go a long way towards clarity in our discussion. This is why I have expressly denoted the “generative” aspect of Generative AI in contrast to mere ‘use of a tool’ as what many are in a hurry to call “AI.” I am NOT including in this designation the many ‘expert systems’ of mere plug in “X” and always get out “Y.” There is no “creative” there, there.

I am NOT including in this designation “presentation of underlying uncopyrightable data or information,” as (it should be abundantly clear), that is NOT what is meant by Generative AI.

A problem with your ‘string argument’ which I attempted to dissuade you from with my rebuttable of including the human manufacturer of the camera and film, is that you seek to place a controlling human at the specific points of “conceptualization, determination of theme, choice to apply a known style in a new context, and other choices regarding presentation” when – explicitly – it is a non-human for one or more of those that IS the point of Generative AI.

It is in this explicit sense that the black and white of Fraud for a human claiming MORE than that human has a right to that is simply NOT pretending – as you seem to want to continue to assert.

As to whether or not this factual scenario may potentially chill creatives, that very much depends on the facts of WHAT is created, and WHAT is merely a human helper post creation (that we BOTH can agree to for at least this argument’s sake to NOT rise to the level of earning copyright).

Just Eric

December 19, 2023 11:58 amAnon–One aspect you may be oversimplifying here is that “generative AI” represents a broad spectrum of capabilities. I have no doubt that some crosses the line, and “for hire” status has been abused in past, but at least some of the initial tools given the generative AI label are little more than research assistants compiling information responsive to detailed prompts. The purposes of copyright still apply to the extent that human authors drive conceptualization, determination of theme, choice to apply a known style in a new context, and other choices regarding presentation of underlying uncopyrightable data or information. Too quickly pretending that it is black and white (fraud!) serves to potentially chill creators from spending time on creatively employing new tools.

Anon

December 19, 2023 09:51 amJust Eric,

The thing with generative AI is that the POST AI ‘work’ is the work of “human assistants,” and does not rise to the heart of the creative aspect to be awarded.

“Clean-up” is an assistant-level item. The patent side has its equivalent.

And this does lead to your assertion of, “but it is not fraud for a claimant or his representative to make a case for authorship in circumstances similar to those described above.” to be false – factually and legally.

Just Eric

December 18, 2023 07:40 pmAnon: “You are not wanting copyright protection in cases in which no such protection should exist, do you?”

No, and I also don’t want copyright denied for use of AI which amounts to the equivalent of human assistant(s). Even an army of human assistants or equivalent AI does not necessarily lessen the value of a driving human author, and the purpose of promoting creative endeavors. There might be good faith debates on the degree of human creativity required, but it is not fraud for a claimant or his representative to make a case for authorship in circumstances similar to those described above.

Anon

December 18, 2023 10:53 amJust Eric,

Let me add:

“and fraud seems too strong a label even if”

No. Fraud is the proper legal term for this legal domain when a person claims a right that they do not have a right to. It is not a matter of feelings (emotion), as it is a factual matter.

Frank

December 17, 2023 08:11 pmmaybe they could ask AI to come up with a winning legal argument?

Anon

December 17, 2023 06:20 pmJust Eric,

Please explicate your “primary concern.”

You are not wanting copyright protection in cases in which no such protection should exist, do you?

Just Eric

December 17, 2023 11:07 amThis is a great statement of my primary concern on this topic:

“attempts to date as to creatives wanting to assert (somehow) that the input side violates copyright law is – while not yet formally adjudicated – is in my view of the law, a non-starter, as dead-end, and NOT a violation of copyright law.”

Regarding the rest, my sense is that “for hire” has already been regularly abused in copyright to go beyond clearly directed activities (especially given the protection over expression rather than ideas). That is likely also the case in invention factories where managers become co-inventors even where they had no real part in conception. This will likely continue and fraud seems too strong a label even if we might generally agree that it pushes past the definition of authorship or inventorship.

Anon

December 17, 2023 10:22 amThanks Just Eric,

As is often the case, blogs tend to sharpen contrasts more often that show overlap of positions.

That’s just the nature of the forum.

With that in mind, and aiming for more overlap (perhaps) and a more clear view of non-overlap, I am hoping that you can rephrase your last paragraph (and keeping in mind that the patent and copyright applications of generative AI may themselves have some overlap and some non-overlap).

Specifically, you mention “tradition” as to not providing protection to what I would label as mere helpers (those who did the bidding at the direction of a creator). You seem to conflate though this type of action with “only” some creation of first draft on existing works.

You do realize that mere following of another does NOT reach the aspects of generative AI.

This is why making sure the topic is clear, and that we are NOT talking about “AI” that is not something – as often confused – merely a t001. The direct point at hand – and a critical element to be recognized is that an output is indeed created that neither the ‘mere helpers” NOR the one directing the mere helpers can rightfully claim to have in mind as the output.

With generative AI, the author can NOT be traced to a human as the prime director.

Certainly, a human can moditfy what the non-human has created (and THIS may be an area to which we might find some agreement).

As to you wanting to switch from inputs to output, I would concur in so fart as the attempts to date as to creatives wanting to assert (somehow) that the input side violates copyright law is – while not yet formally adjudicated – is in my view of the law, a non-starter, as dead-end, and NOT a violation of copyright law.

One is left then (IF one is attempting to find some anchor in copyright law) with the outputs. But as I noted above in regards to “generative,” this too will not work given that the actual output of the generative AI engine cannot trace to a human creator, and thus, no human can be guilty on the output side.

And while your interest may not extend to the patent sense, others more knowledgeable of the law may be able to follow the logic as I have provided with my comment at December 13, 2023 06:31 pm on the https://ipwatchdog.com/2023/12/11/exploring-misguided-notion-merely-computer-negates-eligibility/id=170464/ thread.

As to your first paragraph, let me clarify my takeaway from a legal perspective, as the legal dynamics did NOT result from any level of “contention” raised by PETA. The differentiation is not one of emotion, but of facts. I “get” that you want to insert human actions into the “AI chain,” but that is legal error, as it is NOT the entire chain that is the focal point of the legal question. Were it to be, then the macaque case would necessarily have to draw in the entire chain, from human manufacture of camera and film, to human placement (not an act of creativity in leaving a camera in place with no intention/control of a wild animal to pick up/pose/take a picture or the like. This is why that case turned out as it did and NO HUMAN could be credited with the item of artistic creation.

This is NOT to be confused that no such item existed, or was created – which is a point of legal confusion that many of many attorney brethren have made. This then points to the fallacy of your suggestion that “value” was necessary to have been conferred by human, as this is simply not so.

Just Eric

December 15, 2023 01:37 pmAnon–We are at least close to same page on what issues are, though I do take a different view on the minimal human creativity required to validly claim copyright. If PETA had not gotten involved with macaque selfie case, arguments about the human inputs into camera setup, location, frame selection would have been less contentious, just as human authorship is recognized for wildlife video. Similarly, there is not really any generative AI which is unprompted, and human curation is required at some level to confer value.

With a tradition of recognizing non-fiction authorship from individuals who employ human research and writing assistants–often creating first drafts informed by, or “trained on” a library of copyrighted works–my take is that there is too much stressing over the input/tools side of creative works, and transformative/infringing use is what authors should focus on and be held accountable for with respect to AI tools.

Anon

December 14, 2023 05:12 pmJust Eric,

Certainly, I concur as to a spectrum. Most all of that spectrum – given the power of AI – will merely result in some ULTRA-THIN copyright protection – IF that ‘level of creativity’ aspect is met.

At the end of the day though, just because a photographer leaves his camera about, and a Simian picks it up (without changing any settings) and snaps a selfie, the photographer would be engaging in fraud in attempting to take credit for the picture.

Mind you – the driver of the discussion is generative AI. As I have posted elsewhere, the fact of the matter that generative is involved provides a Hobson choice (this directly in my patent law example, but no less so in the copyright context).

Just Eric

December 14, 2023 03:43 pmAnon: “Claiming something that is not yours is fraud.”

Clearly, but that appears to be simplistic way of avoiding issue of what degree of technical assistance makes it “not yours” if you are curating inputs, managing technical tools, and selecting outputs. Clearly there is spectrum of assistance which has been acceptable, to include human research, writing, and editorial assistants, spelling and grammar checkers, and various software visual editing tools

Anon

December 14, 2023 09:38 am“Am I wrong to suspect that there would have been no problem with the registration had he not tried to list a software application as co-author?”

Yes, you are wrong.

Claiming something that is not yours is fraud.

“borrowing from the style”

Style is not an item protected by copyright.

Just Eric

December 13, 2023 04:51 pmAm I wrong to suspect that there would have been no problem with the registration had he not tried to list a software application as co-author? It would be simple enough to emphasize human curation and choices involved, especially if the image at issue were in a larger collection, such as a children’s picture book. It seems that too many academics and politicians are concerned with use of IP in AI without distinguishing whether the use of IP means simple consumption–such as in research or by an assistant–or appearance of IP in productive output to a sufficient degree to be considered infringing. Here, even if Van Gogh’s work were still under protection, there seems to be a fair case for transformative use and borrowing from the style.

Anon

December 12, 2023 08:10 amThe AI work IS fully in the public domain.

The original photograph? Sure, that is not. But you cannot get from the photograph to the AI work as NOT being fully in the public domain.

I suggest that you review your understanding before posting such an errant viewpoint.