“The Section 145 Trilogy may not have only tamed potential drawbacks of filing a Section 145 action – but at least one of the cases (Kappos v. Hyatt) may have provided a basis that patents issued responsive to these actions are particularly valuable because they are not susceptible to invalidity challenges before the USPTO.”

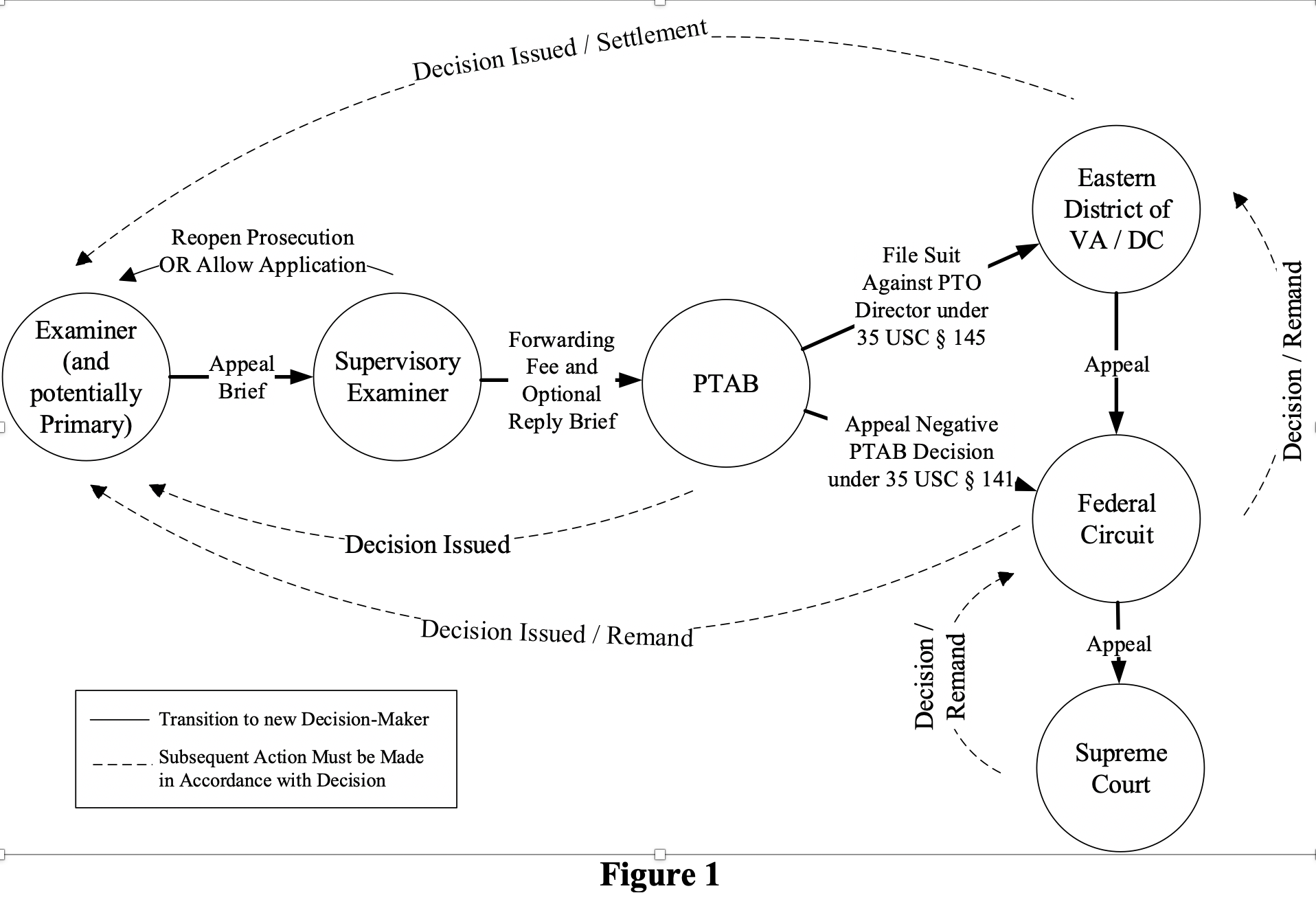

Typically, patent examiners are the prominent decision-makers controlling whether patent applications are allowed. However, Applicants have the power to change who controls these decisions. For example, each Examiner’s Answer must be approved by a supervisory examiner, so filing an Appeal Brief results in the supervisory examiner reviewing the rejections at hand, the appellant’s arguments, and the examiner’s responses to the appellant’s arguments. (If the supervisory examiner agrees with the appellant, then the application is either allowed or prosecution is reopened with one or more new rejections). So long as prosecution is not reopened, paying the Forwarding Fee subsequent to receiving the Examiner’s Answer results in jurisdiction shifting to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

Typically, patent examiners are the prominent decision-makers controlling whether patent applications are allowed. However, Applicants have the power to change who controls these decisions. For example, each Examiner’s Answer must be approved by a supervisory examiner, so filing an Appeal Brief results in the supervisory examiner reviewing the rejections at hand, the appellant’s arguments, and the examiner’s responses to the appellant’s arguments. (If the supervisory examiner agrees with the appellant, then the application is either allowed or prosecution is reopened with one or more new rejections). So long as prosecution is not reopened, paying the Forwarding Fee subsequent to receiving the Examiner’s Answer results in jurisdiction shifting to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB).

If the PTAB affirms a rejection, the Applicant can appeal the decision to the Federal Circuit (under 35 U.S.C. § 141) or can file a civil action (a complaint) against the USPTO Director in the Eastern District of Virginia (under 35 U.S.C. § 145). If no such appeal or civil action is filed, then the USPTO is to issue an action (an office action if the Examiner identifies a new rejection or otherwise either an allowance or abandonment notice depending on whether at least one claim is free of all rejections). Similarly, once a decision has been issued in a Section 141 or Section 145 action, jurisdiction then passes back to the USPTO (unless the decision is appealed) for the USPTO to proceed as instructed in the decision. Figure 1 illustrates how different decision-makers can be involved during prosecution of a patent application.

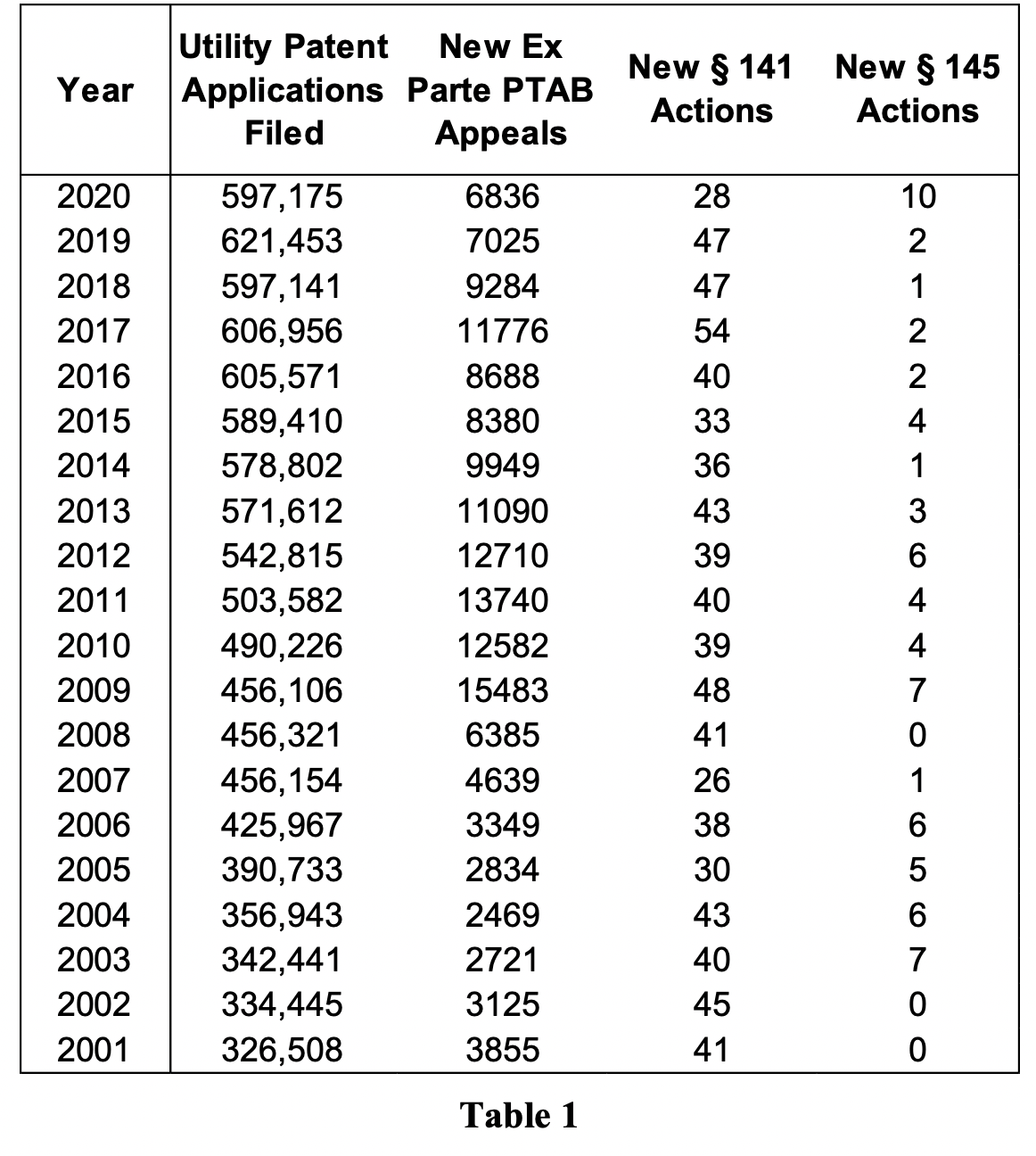

Table 1 shows – for each of the last 10 years – the number of new: filings of U.S. utility patent applications, appeals to the PTAB, Section 141 appeals to the Federal Circuit, and Section 145 actions at the Eastern District of Virginia or the District of Columbia. The counts for the 141 and 145 actions were estimated by querying the text of decisions issued in these jurisdictions. Across years, there were:

- 68-3.4 new ex parte appeals for every 100 new utility filings; and

- 0-0.26 § 145 Actions for every 100 new ex parte appeals.

Notably, there is a delay between when an application is filed and when it may be poised for an ex parte appeal (as at least two office actions would have needed to issue). Similarly, there is a delay between when an ex parte appeal is filed and when it is ripe for a Section 145 action. However, these ratio ranges are rather consistent even when time-shifting the appeal filings relative to the new filings by 2-3 years or time-shifting the Section 145 actions relative to the appeal filings by 2-3 years.

So why do most Applicants decide not to change their decision-maker? Many potential explanations involve weighing the predicted cost (e.g., relating to government and attorney fees and time delays that may impact the value of a patent) and/or predicted likelihood of success (securing high-value patent claims) of various strategies. However, the Eastern District of Virginia is actually known as the “Rocket Docket” and has an average time-to-trial of only six to eight months from the scheduling conference. Further, a series of judicial decisions have drastically changed the risk-benefit analysis that can be applied to Section 145 actions.

Kappos v. Hyatt – Applicants can Introduce New Evidence in Section 145 Actions, Which are Not Appeals of Agency Action

The first case of the Section 145 Trilogy is Kappos v. Hyatt, 566 U.S. 431 (2012), a Section 145 action to contest written-description rejections. The applicant (Gilbert Hyatt) submitted evidence concerning written description support for the claims at issue. The questions at issue were whether new evidence could be presented in a Section 145 action and whether – if new evidence is introduced – the standard of review in Section 145 actions is the deferential “substantial evidence” standard or is “de novo” review.

The Supreme Court noted that the text of Section 145 does not include any limitations on what evidence may be submitted. The histories of Section 145 and of similar predecessor statutes were then considered. The Court observed that, the 1836 Act stated that the district court would “adjudge” whether an Applicant who filed a bill in equity was “entitled, according to the principles and provisions of [the Patent Act], to have and receive a patent for his invention”. The Court further turned to Butterworth v. United States ex rel. Hoe, 112 U.S. 50 (1884), which held that a predecessor statute of Section 145 identified a corresponding proceeding that should be “prepared and heard upon all competent evidence adduced and upon the whole merits”. Thus, the Court held that new evidence is permissible in Section 145 proceedings so long as the introduction of such evidence complies with the Federal Rules of Evidence and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The Court also reasoned that a deferential review standard “makes little sense” given that new evidence (that the USPTO would not have previously seen) can be submitted in a Section 145 trial. While the USPTO argued that – in accordance with the doctrine of administrative exhaustion – Applicants should be required to present evidence first to the USPTO, the Court disagreed. Rather, the Court concluded that the agency’s examination is complete at the point that a Section 145 trial commenced and that a district court is well-equipped to evaluate new evidence and act as a factfinder. Thus, the Court held that the district court is to make de novo findings when new evidence is introduced on a question of fact. The Court also explained that, unlike Section 141, Section 145 is not an appeal and that it “does not provide for remand to the PTO.”

Peter v. NantKwest, Inc. – Applicants are Not Responsible for the USPTO’s Attorney Fees in Section 145 Actions

The second case of the Section 145 Trilogy is Peter v. NantKwest Inc., 140 U.S. 365 (2019), which focused on challenges to obviousness rejections. The district court granted summary judgment to the USPTO, and the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision. However, the reason that this case is included in the Section 145 Trilogy is unrelated to the obviousness decision.

As noted above, Section 145 includes a statement: “All the expenses of the proceedings shall be paid by the Applicant.” In the underlying decision the PTO, for the first time, contended that portions of the salaries of the USPTO attorneys and staff who worked on the litigation qualified as “expenses of the proceedings” that were due from the Applicant.

In short, the Supreme Court disagreed. The Court reasoned that the “American Rule” is a principle that provides a strong presumption that parties must pay for their own attorney fees. The Court noted that this presumption was all the more important when interpreting the Section 145 statute, because the Applicant shoulders the expenses of the proceedings regardless of which party prevails. The Court noted that, the USPTO’s position would mean that an Applicant who successfully demonstrates that a patent should have been allowed by the USPTO would be burdened with paying the agency’s attorney fees.

In its reasoning, the Court turned to a dictionary definition of the word “expense” and found it to be consistent with either interpretation (as including attorney fees or not). Meanwhile, the term “expenses of the proceedings” was found to be similar to a Latin term expensaelitis, which the Court determined would not have been interpreted as including attorney fees. Finally, the Court determined that legislative history indicated that Congress understands the term “expenses” as being different from and not inclusive of “attorney fees”.

Thus, the Supreme Court held that the USPTO is responsible for its own attorney fees in Section 145 actions.

Hyatt v. Hirshfeld – Applicants are Not Responsible for the USPTO’s Expert Witness Fees in Section 145 Actions

The third case of the Section 145 Trilogy is Hyatt v. Hirshfeld, Case Nos. 20-2321;–2325 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 18, 2021). This recent precedential Federal Circuit case stemmed from another Section 145 action, where the district court had ordered the USPTO to issue some of the applications as patents (though this holding has been vacated and remanded based on laches analyses) and further to pay a portion of Hyatt’s attorney fees. The USPTO requested that Hyatt pay the agency’s expert witness fees, per the Section 145 recitation: “All the expenses of the proceedings shall be paid by the Applicant”. The district court cited the NantKwest decision and by applying the same reasoning therein, held that “expenses of the proceedings” do not include expert witness fees.

As in NantKwest, the Federal Circuit analysis in the decision began by noting that the American Rule presumption is a strong presumption and that it applies unless Congress provides a “sufficiently ‘specific and explicit’ indication of its intent to overcome … the presumption”. While the Federal Circuit characterized the issue as to whether “expenses” include expert witness fees as a “close case”, it identified the American Rule as “set[ting] a high bar” and that the USPTO’s arguments had not identified any sufficiently specific and explicit indication that the presumption is overcome in Section 145.

Thus, the Federal Circuit held that the USPTO is responsible for its own expert witness fees in Section 145 actions.

Advantages of Section 145

The cases in the Section 145 Trilogy have seemingly cut the cost of Section 145 actions in about half (if not more, as explained momentarily), assuming that the USPTO attorney fees and expert witness fees are roughly equal to those of the Applicant’s. Further, the Applicant is free to present new evidence and to receive de novo review.

Does Kappos v. Hyatt Mean that Section 145 Patents are Immune from AIA Challenges?

So the Section 145 Trilogy has decreased the constraints and costs of Section 145 actions, but the Kappos v. Hyatt case has potentially also provided at least one large advantage of filing a Section 145 action—a clarification that it is not an appeal and that the court issues a judgment—not a remand—at the end of the proceeding. Indeed, whereas Section 141 specifically provides that an applicant “may appeal the [PTAB]’s decision to the … Federal Circuit,” Section 145 provides that the applicant “may… have remedy by civil action against the Director.” The district court in a Section 145 action renders judgment as a fact-finder—the Federal Circuit does not.. A law review article authored by Michael S. Greve theorizes that a patent that arises out of a Section 145 action is a “gold-plated patent” that is immune to AIA-trial challenges and ex parte reexaminations. Specifically, Greve notes that Kappos v. Hyatt established that, with respect to Section 145 actions, the district court is not merely reviewing a determination of the USPTO, but it is providing its own de novo assessment of the evidence and arguments. Greve further explains how an Applicant-favorable decision in these proceedings results in an order to the USPTO to issue the patent (so long as the issue fee is paid and no new rejection ground arises). Greve concludes:

If § 145 patents issue as of right and neither require nor, in the ordinary course, permit further administrative proceedings, it follows a fortiori that the Director cannot then entertain or initiate an administrative review or reexamination proceeding that would divest the patentee of the benefits of a conclusive Article III judgment …. The short of it is that “§ 145 patents” are immune from administrative review and reexamination except under the most unusual circumstances

Specifically, Greve states that a patent granted based on a Section 145 order “has res judicata and estoppel effect in any court; and that preclusive effect cannot be circumvented by means of an administrative reversal and subsequent (deferential) appellate review”. Notably, res judicata requires that the identity of the parties in the two proceedings be identical. However, Greve’s analysis instead relies on the separation of powers doctrine, citing to the Supreme Court decision in Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, 514 U.S. 211, 218 (1995), holding that Congress may not re-open the final judgments of Article III courts or make such judgments subject to executive branch revision. He notes that the Supreme Court – in Oil States Energy Servs., LLC v. Greene’s Energy Grp., LLC, 138 S. Ct. 1365, 1365 (2018) – has held that AIA trials are merely a means by which the USPTO “reconsiders” its own earlier grant of the patent. But such review after a Section 145 judgment by an Article III court is foreclosed under Plaut on separation of powers grounds. Greve suggests that this means that patents issued pursuant to Section 145 decisions are “gold-plated patents”. Specifically, Greve states:

If that reading of Hyatt [that an Applicant-favorable § 145 decision results in the USPTO Director being duty-bound—contingent on the patentee’s payment of the issue fee and provided that no new discovered ground arises—to perform a ministerial act of issuing a patent] is right, a patent issued pursuant to a § 145 proceeding cannot be subject to the AIA’s review and reexamination procedures.

Accordingly, the Section 145 Trilogy may not have only tamed potential drawbacks of filing a Section 145 action – but at least one of the cases (Kappos v. Hyatt) may have provided a basis that patents issued responsive to these actions are particularly valuable because they are not susceptible to invalidity challenges before the USPTO.

While Greve was not contending that these patents are immune to invalidity challenges at a district court, it is important to recognize that the standard of review at a district court in infringement suits is different than that at the PTAB. That is, claim construction at a district court is to first construe the claims based on claim construction principles as identified in Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005) and the Court must then conclude that the claims are invalid using the “clear and convincing evidence” standard (a higher standard of proof). Meanwhile, to invalidate a patent at the PTAB, the Board applies the lower, more easily satisfied, “preponderance of the evidence” standard (e.g., if there is a greater than 50% chance) to determine whether the claims are invalid.

To make matters a bit more complicated, the standard of proof in district court in Section 145 proceeding differs from that in infringement suits and is as the USPTO applies – preponderance of the evidence. Thus, both the claim construction and the standard of proof are identical at the PTAB relative to a district court in a Section 145 action. Accordingly, if a patent applicant suspects that a patent application may lead to a patent that will be challenged, “gold-plating” the patent via a Section 145 action may be a sound strategic decision given the potential benefit of a bar against executive branch revision.

Does the Existence of Section 145 Challenges Help Preserve Confidence in the Patent System?

Additionally, the IEEE (in its IEEE-USA Amicus Curiae Brief at the U.S. Supreme Court in Peter v. Nantkwest, Inc.) proposed a more utilitarian advantage of Section 145 actions:

The fact that this judicial safety net exists for every applicant, instills expectations both at the PTO and with applicants that improve the efficiency and accountability in the examination process, even when Section 145 proceedings are not invoked. The parties’ knowledge that the applicant can file a Section 145 action to displace an otherwise intransigent PTO prosecution, ‘keeps the PTO honest.’ All applicants benefit from this – not only those few who file such civil actions.

The cases in the Section 145 Trilogy have fundamentally altered the cost and the potential benefit of a Section 145 action. Before these cases, the applicant would be burdened with the USPTO attorney and expert witness fees, would be severely constrained regarding their evidence submission, and would be subjected to deferential review. Not only did the Section 145 Trilogy change all of these impediments, but the de novo standard from Kappos v. Hyatt has the potential to make Section 145 patents immune to invalidity challenges at the PTAB (where such challenges may be more likely to succeed relative to the court system).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Junior-AI-Feb-10-2026-sidebar-day-of-webinar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Anaqua-Feb-12-2026-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Ankar-AI-Feb-17-2025-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/LIVE-2026-sidebar-regular-price-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

15 comments so far.

Particularly Pointing Out

November 3, 2021 03:23 pm@12 “You miss and then double down on your miss, and then triple down on your miss.”

Yet I sunk your battleship.

Anon

October 25, 2021 02:41 pmNot sure just what you think my strikes are there, MCI.

Further, do you have anything other than your feelings as to, “The vast majority of clients WILL NOT pay for Section 145 proceedings.“…?

I ask because I truly do not know the answer to THAT supposition. I do know that most of my varied clients are quite satisfied with our firm’s work without the need to pursue an avenue of Section 145, so the question just does not come up for us.

This though is just not the same as whether or not IF that avenue would come up, that a decline to pursue that path would be solely (or even predominantly) cost based.

Moderate Centrist Independent

October 24, 2021 08:51 pmStrike 3, you’re out, anon!

Your usual disconnect from reality betrays you once again.

The vast majority of clients WILL NOT pay for Section 145 proceedings.

Anon

October 22, 2021 10:07 amPPO,

You miss and then double down on your miss, and then triple down on your miss.

MCI (quite possibly you) was not on point.

There is no ad hominem in my reply (clearly you do not understand what that term means).

Your allusion to “innate racism” recalls a past poster’s errant socio-political rant.

Methinks this current moniker is not the only one you go by.

Particularly Pointing Out

October 21, 2021 06:52 pm@9

MCI’s comment is spot-on but given your past comments it comes as no surprise that you made an ad hominem attack rather than a rational argument.

Or is it just your innate racism showing itself?

Here to correct misinformation

October 21, 2021 12:12 pmI’m watching the PTAB Boardside chat right now. The USPTO Solicitor (Mr. Krause) just said (paraphrasing a bit here) “Don’t file 145 actions. You’ll lose.”

Anon

October 21, 2021 09:59 amMCI,

Your comment appears to be an unfounded “naysaying,” and (in addition to your past views) makes me wonder just what your professional relationship is to the innovation sphere.

Julie Burke

October 20, 2021 02:25 pmThank you, Kate, for yet another timely, relevant article. This piece clearly shows how the decision makers change as an application moves up to appeal and beyond.

With respect to Figure 1, I’d like to point out that examiners (primary or otherwise) and supervisory patent examiners do not have the authority to re-open prosecution under 37 CFR 1.198 following a reversal by the PTAB.

Any action re-opening prosecution after PTAB reversal requires the signature of the Technology Center Group Director or the CRU Group Director. See MPEP 1002.02(c)(1) and 1214.07.

Anon

October 20, 2021 02:00 pmMr. Greve’s “suggestion” (with my emphasis):

“theorizes that a patent that arises out of a Section 145 action is a “gold-plated patent” that is immune to AIA-trial challenges and ex parte reexaminations. Specifically, Greve notes that Kappos v. Hyatt established that, with respect to Section 145 actions, the district court is not merely reviewing a determination of the USPTO, but it is providing its own de novo assessment of the evidence and arguments…”

The view of “But such review after a Section 145 judgment by an Article III court is foreclosed under Plaut on separation of powers grounds.” is quite easily circumvented by changing even one iota of the case (as can easily be done in the post grant arena. ANY difference in evidence and arguments, and that difference nullifies even the ‘theory.’

On top of that, I believe that a re-read of Oil States in in order, as that read may provide that the Office is NOT foreclosed (again, except perhaps in an EXACT match case).

IF not an exact match, then the “nullify” is not actually reached (even though the ENDS may be reached – of which, I think that Mr. Malone may be referring to).

Entertained

October 20, 2021 01:20 pmIt is entertaining to watch the USPTO struggle to deal with the major losses that it had in the § 145 appeals and Judge Moore’s two unanimous U.S. Supreme Court wins. See comment 9 in the October 17, 2021, post in IPWatchdog called An Ax(le) Needs Grinding: Can the Federal Circuit Turn the Wheel? So the next defense of the USPTO is to get the victims to ignore § 145, implying that § 145 is too expense. See comment 11 in that October 17, 2021, post and see comment 1 in this post. See also the amicus brief IEEE (in its ) cited to and linked to in this post.

Of course the USPTO’s comments are ridiculous, but it is the best that the USPTO can do under the circumstances. The reason that USPTO’s comments are ridiculous is that the victims, to get benefits from § 145, do not have to file a civil action against the USPTO and do not have to pay a nickel in litigation costs. These benefits are that § 145 provides important checks on the USPTO and helps kept the USPTO “honest.” This protects all patent applicants. See the section in this post called Does the Existence of Section 145 Challenges Help Preserve Confidence.

The U.S. Supreme Court has twice unanimously told the USPTO that § 145 is here to stay.

We look forward to the response of the USPTO’s commenters, which should be entertaining.

Josh Malone

October 19, 2021 10:20 pmThe cost doesn’t matter, only the reliability of the patent grant.

However, I do not believe that the Federal Circuit will agree with Ms. Gaudry and Mr. Greve. The Federal Circuit will say that the fake judges at the PTAB can nullify the decisions of the Article III courts. They have already done so.

Pro Say

October 19, 2021 08:43 pmSuperb exposition Kate.

Virginia, here we come.

Optimistic

October 19, 2021 08:31 pmThe § 145 story would not be complete without giving credit where credit is due – to Judge Moore and her colleagues who resurrected § 145 with two unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decisions and a Federal Circuit decision. See comment No. 9 in the October 17, 2021, post in IPWatchdog called An Ax(le) Needs Grinding: Can the Federal Circuit Turn the Wheel?

As said before, after establishing § 145 forever with two unanimous wins at the U.S. Supreme Court, how will Judge Moore and her colleagues clarify § 101? We are very optimistic.

Easwaran

October 19, 2021 07:45 pmWow, thought provoking! Great article.

Moderate Centrist Independent

October 19, 2021 03:16 pmGreat information but most clients will not pay for it.

Dr. Gaudry, can you share how much a 141 action cost one or more of your clients? I’d love to hear from others as well regarding how much it cost your clients.