“Since 2016, Rule 12(b)(6) and 12(c) motions are more likely to target infringement claims, defenses and remedies.”

Today, district courts evaluate whether patent infringement complaints satisfy the plausibility standard under Fed. R. Civ. P. 8 and the Supreme Court’s Iqbal–Twombly standard. Five years after abrogation of Form 18 (a sample patent infringement complaint that was said to be plaintiff-friendly) and nearly 15 years after Twombly, jurisdictional analyses have diverged. Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) and 12(c) motions have developed into a targeted, widely-used tactic. Both motions provide defendants with a low-risk, high-reward opportunity. As plaintiff or defendant, start by evaluating the possible-to-plausible pleading spectrum.

Abrogation of Form 18

The Complaint–Form 18 combo came to life on February 26, 1983. Fed. R. Civ. P. Amendments Act of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-462, § 3, 96 Stat. 2527, 2527, 2529-30 (Jan. 12, 1983). For direct infringement, Form 18’s minimalistic pleading requirements included an allegation of jurisdiction, a demand for relief, and statements that plaintiff owned the patent, defendant infringes the patent, and plaintiff provided defendant notice of its infringement. In re Bill of Lading Transmission & Processing Sys. Patent Litig., 681 F.3d 1323, 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2012). Notice was similarly satisfied by Form 18, which included: (i) allegation of patent ownership; (ii) defendant name(s); (iii) patent infringed; (iv) means by which defendant infringes; and (v) sections of patent law invoked.

On December 5, 2015, the Supreme Court and Judicial Conference of the United States voted to abrogate the Form and reference thereto. Today, federal district courts evaluate the adequacy of patent infringement complaints under Fed. R. Civ. P. (“Rule”) 8, (see Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(a) (requiring “(1) a short and plain statement of the grounds for the court’s jurisdiction . . . ; (2) a short and plain statement of the claim showing that the pleader is entitled to relief; and (3) a demand for the relief sought”)) and the Supreme Court’s Iqbal–Twombly standard. Together, the plausibility standard requires a context- and fact-specific assessment of the pleadings: whether the factual allegations conceivably support a claim for relief; collectively, whether the pleading plausibly states a claim for relief. Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 570 (2007); Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 663-64 (2009) (citing Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556).

The Rising Tide of Motions to Dismiss

Opportunities to summarily dismiss pleadings at an early stage are directed towards the substance of the infringement pleadings and are fashioned as Rule 12(b)(6), (see Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) (“failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted”)) and 12(c), (see Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c) (“judgment on the pleadings”)) motions. The court’s review of either is strictly limited to the contents of the parties’ pleadings, documents attached thereto, and judicially noticed facts that inform the plausibility of the pleading(s).

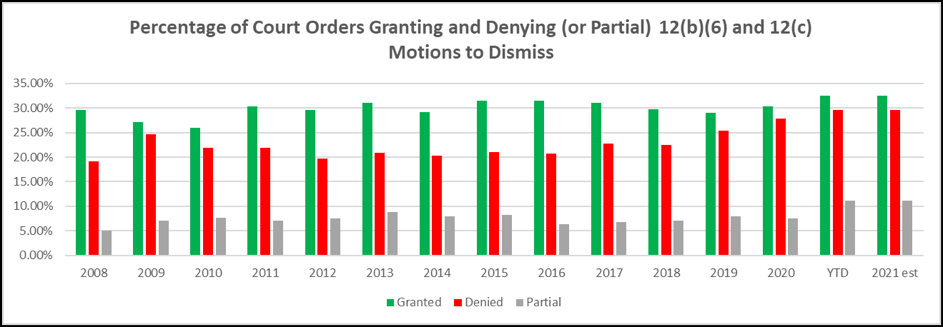

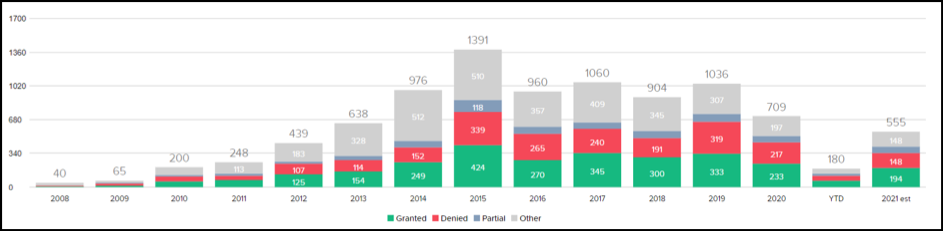

At first glance, Form 18 seems to have had the recent effect of closing the gap in Rule 12(b)(6) and 12(c) grants and denials.

Fig 1: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Success Rate for Contested Motions to Dismiss Patent Infringement Claims, Defenses, and Remedies

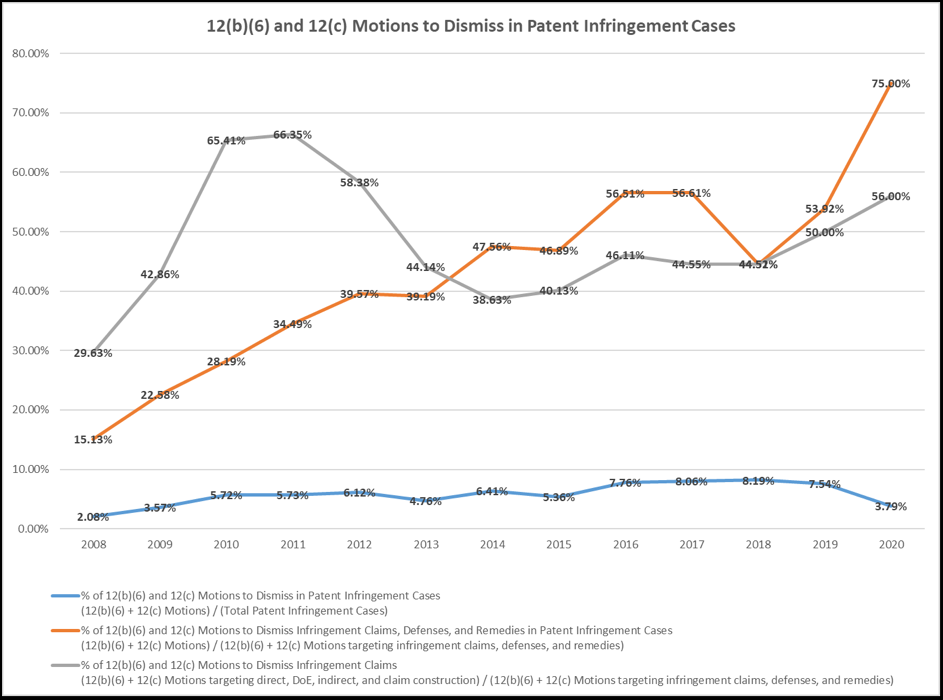

Calculated from the data in Figs. 3-5 below, the percentage of patent infringement cases with 12(b)(6) and 12(c) motions has hovered around the 8% mark since 2016 (excluding 2020). However, since 2016, Rule 12(b)(6) and 12(c) motions are more likely to target infringement claims, defenses and remedies. Even more specifically, and as identified by Fig. 2, parties whom file such motions are more-and-more likely to raise issue with pleadings that target direct infringement, indirect infringement, infringement by doctrine of equivalents, and claim construction-related disputes.

Fig 2: Comparison of 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Motion to Dismiss Prevalence in Patent Infringement Cases

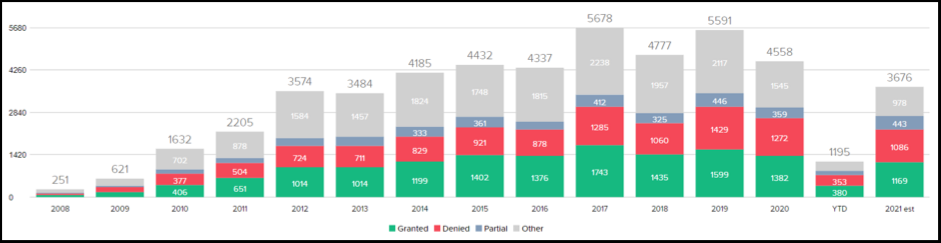

Fig 3: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Motion to Dismiss Infringement Claims (Direct, Indirect, DOE, Claim Construction) and Infringement Defenses (Invalidity, Unenforceability, Non-Infringement)

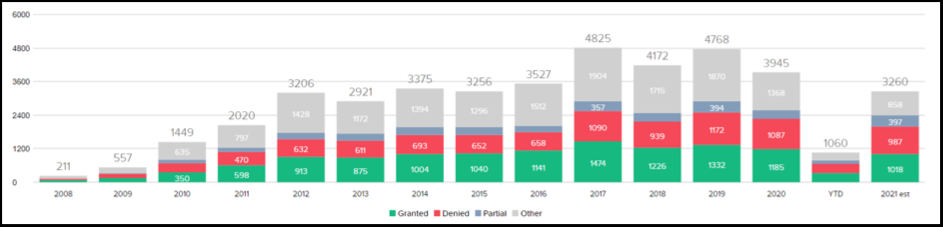

Fig 4: 12(b)(6) Motion to Dismiss Infringement Claims (Direct, Indirect, DOE, Claim Construction) and Infringement Defenses (Invalidity, Unenforceability, Non-Infringement)

Fig 5: 12(c) Motion to Dismiss Infringement Claims (Direct, Indirect, DOE, Claim Construction) and Infringement Defenses (Invalidity, Unenforceability, Non-Infringement)

The Spectrum of Pleading Infringement

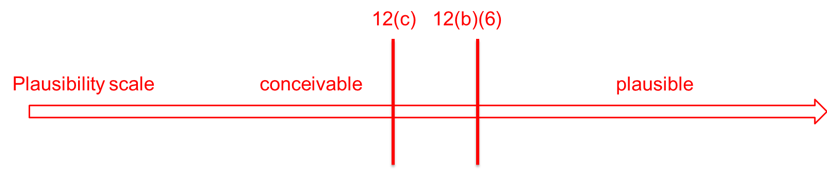

There is a sliding plausibility scale for each infringement claim. Courts inherently develop a scale to assess whether the pleading satisfies the jurisdiction’s interpretation of the plausibility standard and comports with fair notice.

Fig 6: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Motion to Dismiss Plausibility Scale

When constructing the pleadings, consider 12(c) a more fundamental requirement. The pleadings must meet some lower threshold, beyond “implausible” or “merely conceivable.” If pleadings satisfy 12(c), they may not satisfy 12(b)(6); on the other hand, if the pleadings fail to satisfy 12(c), they cannot satisfy 12(b)(6). As 12(c) is a more fundamental requirement, there are demonstrably fewer 12(c) motions filed in any district court. Interestingly, since 2016, the denial rate for Rule 12(c) motions has consistently trended higher than 12(b)(6) motions. See infra Fig. 4, 5 (approximately 4% higher). Also since 2016, the Rule 12(b)(6) motion grant rate has fluctuated more than the 12(c) motion grant rate. See id.

After constructing the foundational pleading(s), recognize that “[t]he plausibility standard ‘does not impose a probability requirement at the pleading stage; it simply calls for enough facts to raise a reasonable expectation that discovery will reveal evidence’ to support the plaintiff’s allegations.” Nalco Co. v. Chem-Mod, LLC, 883 F.3d 1337, 1350 (Fed. Cir. Feb. 27, 2018) (quoting Twombly, 550 U.S. at 556). When conducting the plausibility analysis, the court will assess whether the pleading surpasses or satisfies this threshold, which is “a context-specific task that requires the reviewing court to draw on its judicial experience and common sense.” Iqbal, 556 U.S. at 679. The Court will take the pleadings and exhibit(s) together, and construe any disputes in plaintiff’s favor.

In Disc Disease Sols., Inc. v. VGH Sols., Inc., 888 F.3d 1256 (Fed. Cir. 2018), the Court assessed the simplicity of the accused device and patent, and found a conclusory allegation of infringement to be sufficient. 888 F.3d at 1250-60, 1260 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 2018). The complaint in Disc Disease alleged in conclusory fashion: “each and every element of at least one claim” is infringed by the accused product. Id. at 1258, 1260. The Federal Circuit held that the allegations in Disc Disease were “enough to provide [defendant] fair notice” where the Plaintiff attached copies of the asserted patents, “photos of the product packaging” and the case “involve[d] a simple technology.” Id. While pictures were capable of sufficiently informing the pleadings in Disc Disease, a detailed and substantive claim chart attached to the complaint were insufficient for more complex technology in Golden. Compare Golden v. Apple Inc., 819 Fed. Appx. 930, 931 (Fed. Cir. 2020) (“vague generalities” and “cryptically identified structures”) with Disc Disease, 888 F.3d at 1260 (“simple technology” identified “by name and by . . . photo[]” satisfy “fair notice”).

Numerous district courts continue to engage in the simple-complex technology assessment. See, e.g., Belair Elecs. v. Carved, 2021 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 64449, at *9-10 (N.D. Ind. Apr. 2, 2021); Liqui-Box Corp. v. Scholle IPN Corp., 449 F. Supp. 3d 790, 798 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 27, 2020); Signify N. Am. Corp. v. Axis Lighting, Inc., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 37899, at *4-5 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 4, 2020); Super Interconnect Techs. LLC v. Sony Corp., 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 164814, at *6 n.1 (D. Del. Sept. 26, 2019); Larson v. SoundSkins Glob., 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 138219, at *7-9 (D. Minn. Aug. 15, 2019); Election Sys. & Software, LLC v. Smartmatic U.S. Corp., 2019 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 34738, at *5 n.3 (D. Del. Mar. 5, 2019); Inhale, Inc. v. Gravitron, LLC, 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 223241, at *5 (W.D. Tex. Dec. 10, 2018); KOM Software Inc. v. NetApp, Inc., 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 199388, at *5 (D. Del. Nov. 26, 2018); Gamevice, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 221777, at *9-12 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 6, 2018); CLM Analogs, LLC v. James R. Glidewell Dental Ceramics, Inc., 2018 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 225319, at *7-9 (C.D. Cal. June 19, 2018).

Direct Infringement

Often, defendant is requesting the court find the pleading fails to plausibly allege a term’s construction or plausibly support a claim of infringement as a matter of law. Because defendants request the court bypass a two-step construction and comparison process, see Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1203 (Fed. Cir. 2005), plaintiff is tasked with convincing the court that further discovery or construction is required.

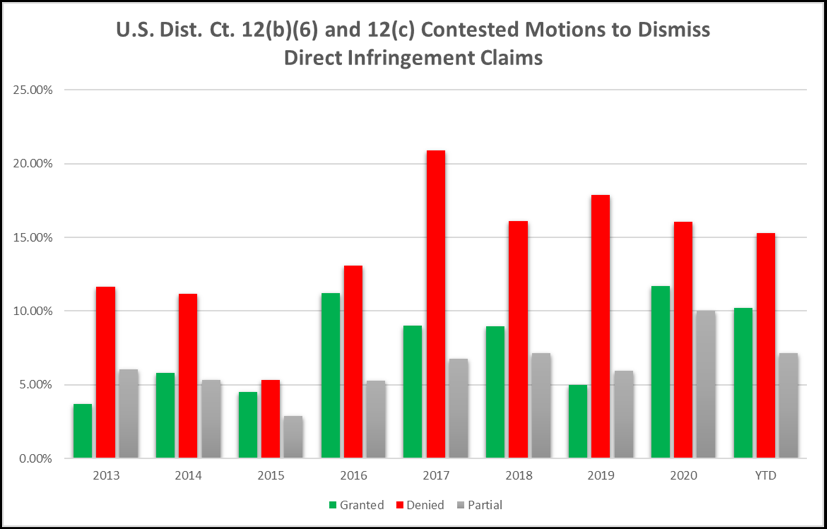

The direct infringement data, below, was parsed to only include acts of infringement and comparison of claims to the accused product or process; denials are decreasing, and grants are on the rise and likely to continue.

Fig 7: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Contested Motions to Dismiss Direct Infringement Claims for Failure to Plead: (i) acts of infringement, and/or (ii) comparison of claim(s) with accused product/service/process (excluding Hatch-Waxman and Biologics cases)

Direct Infringement by DOE

Direct infringement by doctrine of equivalency is properly pled when claim limitations are not literally present in the accused product or process, but are present by equivalency. At the pleading stage, plaintiff must merely state that the infringement satisfies the limitation by equivalency. For instance, in Nalco, Plaintiff satisfied the “injecting” claim element by pleading the accused device achieves the same function as the claim in substantially the same manner. 883 F.3d at 1354.

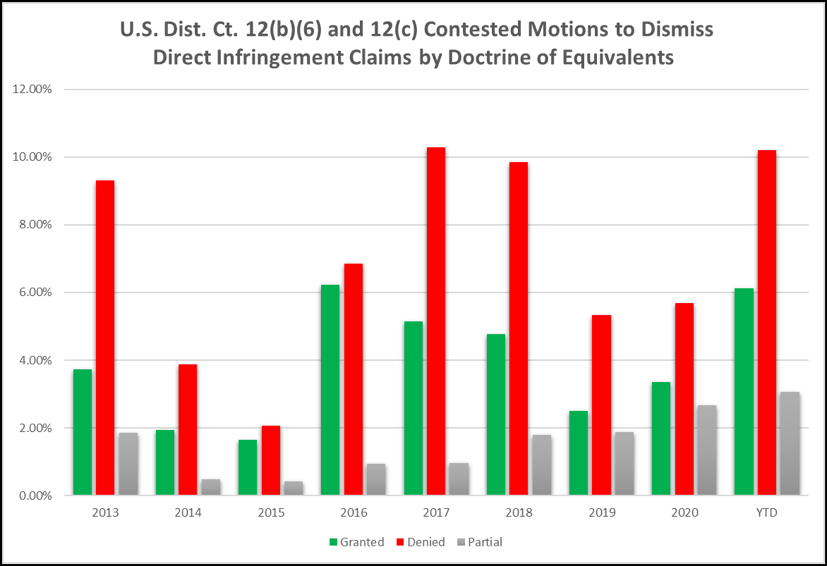

The direct infringement by doctrine of equivalency data, below, was parsed to only include all elements rule, function-way-result test, insubstantial differences, and scope of equivalents; grants are returning to 2016 levels but with more denials—likely a representation of the ease with which a party may properly plead infringement by equivalency.

Fig 8: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Contested Motions to Dismiss Direct Infringement Claims for Failure to Plead Direct Infringement by DOE

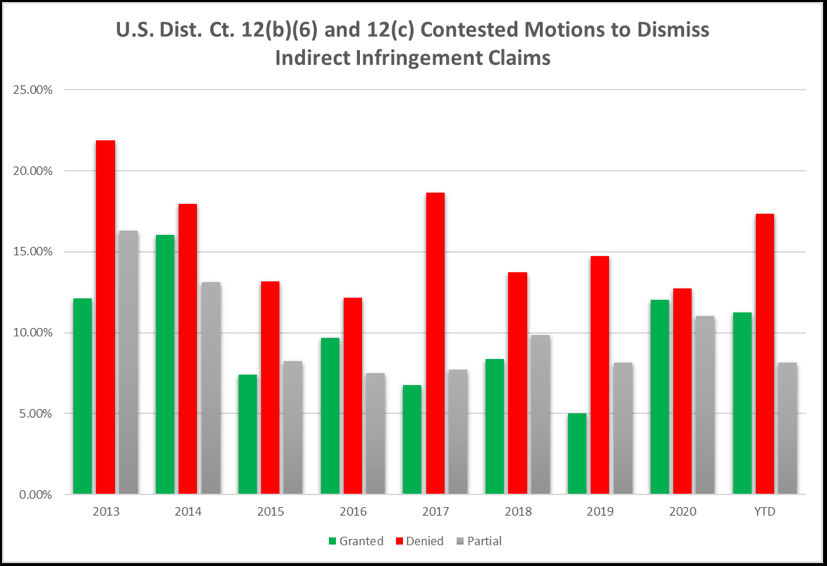

Indirect Infringement

Prior to abrogation of Form 18, there was no form complaint for claims of indirect infringement (i.e., induced or contributory); abrogation of the Rules should not have changed the pleading standards for indirect infringement claims. In re Bill of Lading, 681 F.3d at 1336-37. However, the data below shows grants are increasing and realistically capable of reaching a new, high-water mark in 2021 or 2022. Interestingly, there are approximately double the number of motions to dismiss induced infringement claims as contributory infringement claims, mostly which are failure to plead intent to induce infringement. Evidentially, defendants see an opportunity that was not discernable in 2016—we are likely trending toward a phase where courts deny fewer motions to dismiss or, are less-and-less likely to grant dismissal than deny dismissal.

Fig 9: 12(b)(6) and 12(c) Contested Motions to Dismiss Indirect Infringement Claims for Failure to Plead: (i) induced infringement, (ii) contributory infringement, and/or (iii) underlying direct infringement claim(s)

Thoughts for Plaintiff

As Plaintiff, consider the limits and breadth to your infringement claims; and as a bare-minimum, plead sufficient facts to avoid dismissal with prejudice. Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178, 182 (1962); see Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a)(1)(B); Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(a)(2). Make sure to always:

- identify the accused product(s) or process(es) as clearly as possible; then,

- gauge the simplicity vs. complexity dichotomy (e.g., regional circuit case law and any federal district court experience with the patented or accused technology); and

- plead key claim elements or limitations that are plausibly infringed, either literally or by doctrine of equivalents.

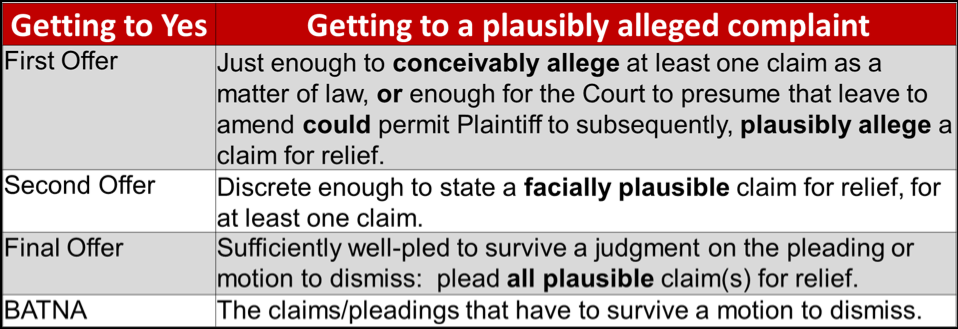

If Defendant chooses to frame a dispute with the adequacy of the pleadings, Plaintiff should leverage the well-established principle that courts generally grant leave to amend the complaint. As such, Plaintiff should opportunistically build its infringement claim(s) in accordance with a “Getting to Yes” negotiation strategy, by gauging the comfort-level of the court and gaining the greatest breadth or scope for your infringement claim:

Table 1: Negotiating the Breadth of Infringement Pleadings: Analogy to Fisher, Ury, and Patton, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (1991)

Thoughts for Defendant

As Defendant, consider the value of your potential 12(b)(6) or 12(c) motion:

- whether leave to amend will be granted;

- whether the motion will merely cause delay and expense; and

- whether Defendant risks providing Plaintiff a ‘second bite’ (i.e., an opportunity to correct deficiencies or increase Defendant’s risk, damages, or liability).

Indeed, Defendant may have a greater chance of success by moving for judgment on the pleadings at a later stage. Alternatively, Defendant may have an opportunity to seek transfer to a venue with more stringent pleading requirements or more likely to grant dismissal.

Diverging Analyses Require Careful Strategies

Five years after abrogation of Form 18 and nearly 15 years after Twombly, jurisdictional analyses have diverged. As plaintiff, ensure sufficiently pled facts support the foundation for a broad, yet plausibly-pled claim. As defendant, gauge the risk-reward opportunity to timely dismiss plaintiff’s key infringement claim(s).

The figures above incorporate data generated by Docket Navigator. Docket Navigator Analytics collects and generates data from all U.S. district court patent cases with electronically accessible dockets, indexed backed to January 2008.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Anon

June 3, 2021 08:33 pmwith post 1, now I am curious as to the Author’s reaction.

Pro Say

June 3, 2021 04:35 pmCurious: “With evidence yet to be presented, how can there be clear and convincing evidence?”

But of course, there cannot be . . .

“But, but, but . . . yaz mean that “C & C” isn’t some type of drink?!”

Doh!

— The CAFC

Curious

June 3, 2021 02:07 pmA huge discussion on 12b6 and not a single mention of 101. Big opportunity missed. Many (perhaps all?) Circuits don’t require plaintiffs to plead facts to preemptively anticipate or overcome affirmative defenses, yet the Federal Circuit continues to bless the use of a 12b6 motion in conjunction with the defense of patent ineligibility under 101.

Under Iqbal/Twombly, the standard is whether the pleading articulates “enough facts to state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face.” In instances of patent infringement, the “claim” is whether the defendant infringes the patent. Nothing about this standard requires the plaintiff to articulate facts to anticipate or overcome the affirmative defense of patent ineligibility.

The issue is whether the defendant was given fair notice of what the claims is (i.e., patent infringement) and the ground upon which the claims rests. Remember, a 12b6 motion is one that alleges failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted. Once the pleader articulates facts for a plausible claim of patent infringement, that should be the end of it. Again, nothing about that requires the pleader to anticipate or overcome an affirmative defense.

Under 35 USC 282, a patent is presumed valid. Under i4i, claims can only be invalidated by clear and convincing evidence. Moreover, in a motion to dismiss, all factual allegations are construed in a light most favorable to the non-movant (i.e., patentee in a matter involving patent infringement). How can a patent be invalidated for clear and convincing evidence when all factual allegations are construed in a light most favorable to a non-movant? Additionally, in the context of 12b6, this is prior to discovery phase, which means that evidence has yet to be presented. With evidence yet to be presented, how can there be clear and convincing evidence?

I suspect that when you look further at the number of situations in which a motion to dismiss was granted, a very large percentage of those were based upon 101. This is a huge oversight on your part.