“Rather than rely on a court’s coin flip as to whether the use of the copyrighted work to train LLMs is fair use, it may be better to develop a licensing mechanism that rewards publishers without subjecting AI developers to massive statutory damages.”

ChatGPT and similar generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools rely on large language models (LLMs). LLMs are fed massive amounts of content, such as text, music, photographs and film, which they analyze to discover statistical relationships among these inputs. This process, describe as “training” the LLMs, gives them the ability to generate similar content and to answer questions with seeming authority.

ChatGPT and similar generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools rely on large language models (LLMs). LLMs are fed massive amounts of content, such as text, music, photographs and film, which they analyze to discover statistical relationships among these inputs. This process, describe as “training” the LLMs, gives them the ability to generate similar content and to answer questions with seeming authority.

The business community, and society at large, seems convinced that AI powered by LLMs holds great promise for increases in efficiency. But multiple lawsuits alleging copyright infringement could create a drag on development of LLMs, or worse, tip the competitive balance towards offshore enterprises that enjoy the benefits of legislation authorizing text and data mining. A lot seems to hang on the question of whether LLM training involves copyright infringement or instead is a fair use of copyrighted content.

In just one example of the litigation that this has spawned, the New York Times Company recently sued OpenAI and Microsoft, accusing it of massive copyright infringement in the training of the LLM underlying ChatGPT. This litigation, and other cases like it, may force the courts to decide the question of fair use. If they conclude that LLM training is fair use, then the copyright owners will get nothing from this exploitation of their content. If they don’t find fair use, then the LLM owners may be liable for billions of dollars in statutory damages.

This winner-take-all outcome based upon the subjective question of fair use (see, e.g., the majority and dissenting opinions in Warhol v. Goldsmith) calls into question the adequacy of the current legal regime and whether, in the context of the development of AI, the current copyright system will “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” or will unduly hinder it.

Background

Newspapers must provide their subscribers with digital access to their content in order to remain competitive. The New York Times, in paragraph 45 of its complaint against OpenAI, says that on average about 50 to 100 million users engage with its digital content each week. Of those, nearly 10 million are paid subscribers who receive only the digital version of the Times.

To produce its content, the Times employs about 5,800 people, of whom about 2,600 are directly involved in journalism operations. Complaint at ¶38. The Complaint says that “[t]he Times does deep investigations—which usually take months and sometimes years to report and produce—into complex and important areas of public interest. The Times’s reporters routinely uncover stories that would otherwise never come to light.” Complaint at ¶33.

The best legal protection available to the Times is copyright, which the Times takes seriously, filing copyright registrations of its newspaper daily. Unfortunately for the Times, copyright protects the wording used to describe a news event but not the news itself. As the US Copyright Office has said, “[o]ne fundamental constraint on publisher’s ability to prevent reuse of their news content is that facts and ideas are not copyrightable.”

The Times already makes its content available for license through the Copyright Clearance Center. A CCC license to post a single Times article on a commercial website for a year costs several thousand dollars. Complaint at ¶51. At those prices, LLM owners are likely to avoid licensing the content of the Times, preferring to take their chances in court.

The Use of Times Content to Train ChatGPT.

The Times complaint cites disclosures made by OpenAI regarding the training sets used by early versions of ChatGPT. These disclosures identify the Times as the 5th most significant source used to train ChatGPT. Complaint at ¶85. Proving that this is still the case for the current version, an attachment to the complaint provides 100 examples of ChatGPT 3.5 spitting out exact or nearly exact copies of articles that appeared in the Times. Exhibit J to Complaint.

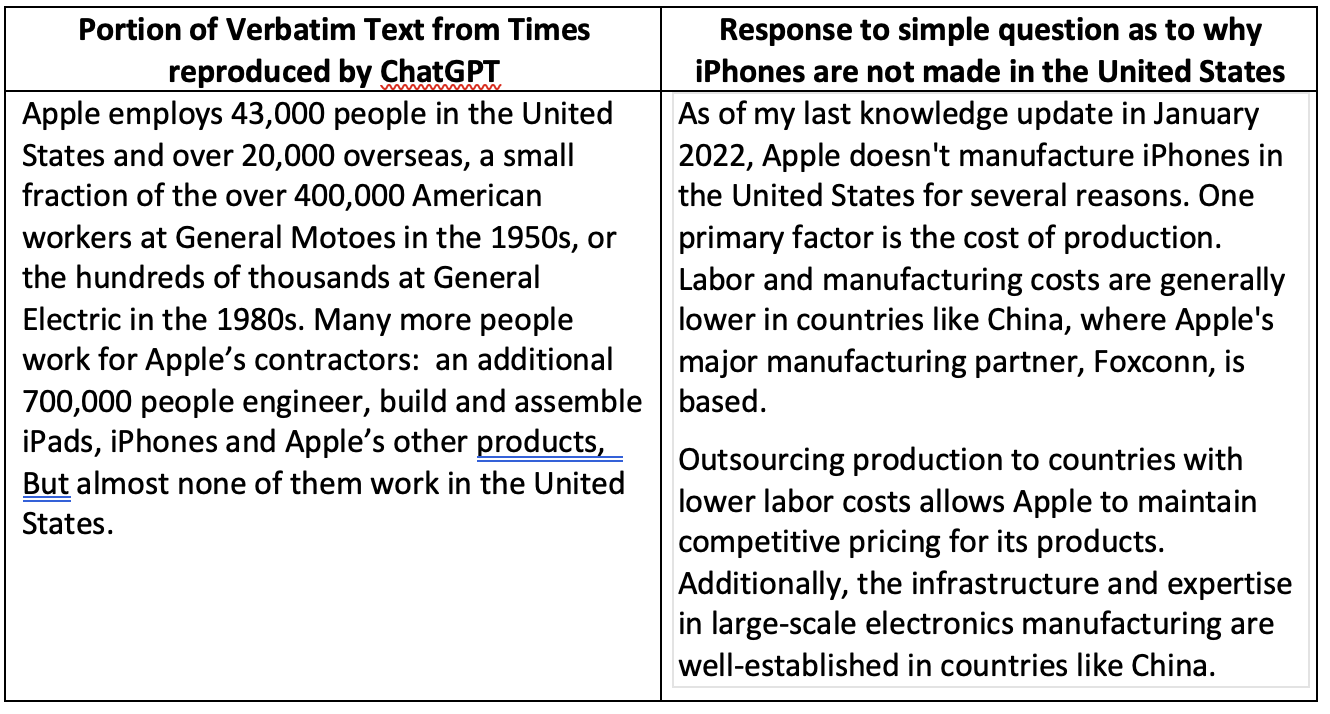

The first example in the Times’s attachment involves an article about a 2012 gathering of Silicon Valley executives at which President Obama asked Steve Jobs what it would take to get Apple to make iPhones in the United States. In order to get ChatGPT to provide a response that clearly involved copying of a Times article, the Times prompted ChatGPT with the first 237 words of the article. ChatGPT’s response included the next 364 words of that same article.

This manner of prompting ChatGPT is not representative of how most people use it. If prompted with the question “Why doesn’t Apple make iPhones in the United States?” ChatGPT provides an entirely different response that does not infringe that 2012 Times article and appears to be a typical example of ChatGPT prose – simple, clinical, well organized with no personality. In other words, what you would expect of a robot.

The Complaint also reports having a user prompt ChatGPT by saying that it was paywalled out of reading a specific article and asking it to type out the first paragraph. ChatGPT cheerfully obliged. When asked for the next paragraph, ChatGPT responded by providing the third paragraph of the article. Complaint at ¶104. One such instance involved an article about the recent Hamas invasion of Israel, not some long-ago archived article. Complaint at ¶112. This poses a real possibility that users could effectively read the Times without visiting its website or using its app.

The Complaint also describes “synthetic search results” in which Bing, powered by AI, returns searches of recent news events that quote large portions of Times articles virtually verbatim. Unlike a traditional search result, the synthetic output does not include a prominent hyperlink that sends users to The Times’s website. Complaint at ¶114.

Is a Statutory License the Answer?

AI developers claim to be on the cusp of a major societal advance. Content owners claim that this is only made possible by the exploitation of their work, exploitation that might or might not be fair use. This situation seems to call for a legal framework that rewards publishers for their efforts but encourages the development of LLMs. Rather than rely on a court’s coin flip as to whether the use of the copyrighted work to train LLMs is fair use, it may be better to develop a licensing mechanism that rewards publishers without subjecting AI developers to massive statutory damages when the primary purposes and uses of the LLM do not involve displacing content owners and their rights.

Regulatory Developments Outside of the United States.

In 2019, the European Parliament and the Council of the EU issued directive 2019/790 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market. That directive authorized research organizations to carry out scientific research using text and data mining (“TDM”) of works to which they have lawful access. It requires those organizations to store the text and data with “appropriate levels of security.” Other organizations were also authorized to engage in TDM, but with the qualification that copyright owners may opt out by, for example, providing a machine-readable notice of reservation of rights in an online publication. Similar laws have been enacted in the UK, Singapore and Japan.

The preference given to research organizations – which are not subject to the opt-out mechanism that applies to commercial organizations engaged in TDM – has given rise to “data cleansing”, in which a non-profit organization engages in TDM and makes its data set available to commercial enterprises. Content owners naturally find this practice to be abusive.

The EU is now developing further guidelines for data mining done to train LLMs. On February 2, 2024, a committee of the European Parliament published a provisional agreement proposing that all AI models in use in the EU “make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used for training the general purpose model.” The summary would list the main data sets that went into training the model and provide a narrative explanation about other data sources used. This falls short of a statutory license regime, however, since copyright owners would then have the ability, under EU directive 2019/790, to opt out of being included in the training set of an LLM.

U.S. Developments

Statutory license schemes already exist in the United States – including one directed to the digital transmission of music. The Librarian of Congress now appoints a three-judge panel, the Copyright Royalty Board, which determines and adjusts royalty rates for such transmissions. See 17 USC §801 at seq. This allows companies to broadcast music without obtaining licenses from each copyright owner. Instead, the broadcaster reports its use of the music to the copyright office and pays the required royalty into a fund that is then distributed to the rights holders of the music that was broadcast. To date, over $10 billion has been distributed in this manner.

A similar mechanism could be established to facilitate the use of data mining of newspaper content for the purpose of training LLMs. Such a system could require the owners of the models to identify the content that was used to train the model and to agree to pay royalties at the rate established by the Copyright Royalty Board, which would then cause the funds to be remitted to the relevant publishers. While such a system would deprive news organizations of the opportunity to negotiate separately for the rights to their content, it could relieve them of the risk that a judicial finding of fair use would deprive them of any revenue from LLMs.

On August 30, 2023, the U.S. Copyright Office asked for comment on several questions involving AI. Among them were questions about copyright licensing:

Should Congress consider establishing a compulsory licensing regime?? … What activities should the license cover, what works would be subject to the license, and would copyright owners have the ability to opt out? How should royalty rates and terms be set, allocated, reported and distributed?

The majority of the comments received have come from content creators or organizations representing them. As you might expect, these comments express opposition to a compulsory license and express with confidence the conclusion that using TDM for LLM training is not fair use. Several comments quote a remark made by Marybeth Peters, then the Register of Copyrights, in 2005: “The Copyright Office has long taken the position that statutory licenses should be enacted only in exceptional cases, when the marketplace is incapable of working.”

However, not all opponents of a statutory license see it the same way. The Computer & Communications Industry Association had this to say: “Congress should not consider establishing a compulsory licensing regime. There is no principled basis for establishing such a regime. Just as a reader does not need to pay for learning from a book, an AI system should not have to pay for learning from content posted on a website.”

In light of the negative reaction to the notion of a statutory license, it seems unlikely that one will emerge unless and until the fair use question is settled in court. However, if the courts find in favor of the AI developers, the tide of opinion will likely shift in favor of statutory reform. That reform could simply exclude training of LLMs from fair use; or it could attempt to bridge the divide between content owners and AI developers by enacting a statutory scheme of compulsory licenses.

Such a system would involve complexities not found in digital music broadcasting, including:

- Hallucinations, or LLM output that that seems realistic but is entirely fabricated. The Times’ Complaint provides examples of “facts” attributed to the Times that it never reported and that are simply untrue

- Revenue loss resulting from lead generation created by AI but originating from a publisher’s content

- Loss of subscription revenue that may arise if AI models displace publishers as sources of information by, for example, reproducing memorized content that is behind paywalls

- The need to require creators of LLMs to disclose the data sets behind their training systems

- Differences between types of content – news, photos and music have different qualities that may require regulatory distinctions.

In short, a statutory license in this realm is not likely soon, but it may become necessary if the courts find that training LLMs on copyrighted material is fair use. By then, guidance from the EU and other jurisdictions considering this issue may be instructive.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: maxkabakov

Image ID: 35878167

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

17 comments so far. Add my comment.

Anon

March 4, 2024 01:51 pm“as that would be unfair to the content owner and would definitely be infringement.”

I laughed. Please read up just a tad on the technology.

Then read up on existing law (Fair Use – see at least the Google cases on scraping and API).

Alex from delevit

March 3, 2024 02:24 pmWell… the comment section is fun!

Here’s my two cents.

Anything that is made publicly available and not opted out from LLM consumption is assumed to be made available to LLMs, to scrape, process and to learn from.

However, the LLMs must not allow the output to be an exact copy of the consumed data or even something that is too similar, as that would be unfair to the content owner and would definitely be infringement. These safeguards will need to be implemented on the LLM side.

The output must be sufficiently different and sufficiently transformed, so as not to be confused in any way with the original content. The output must be nothing more than a derivative work – which falls firmly within fair use.

When LLM users ask for exact content or exact language, the output of the LLM should act as an affiliate advertiser and direct the user to the original content owner’s website. The LLMs that refer new clients should also be paid an affiliate commission for each new subscriber as the owner would pay any other affiliate service.

This would create a win-win-win relationship between AI, content creators/owners and consumers.

Anon

February 28, 2024 12:44 pmPro Say – thank you for your capitulation.

Now it is time to move on.

Pro Say

February 28, 2024 12:21 pm“You HAVE to have more, right?”

My years of comments speak for themselves.

As do yours for you.

Time now to move on.

Anon

February 28, 2024 09:03 amThe breaking of terms of service need not arise to a breaking of any anti-hacking laws.

Don’t be fooled by that misdirection.

Also, don’t be fooled by the Crosby statement – that is a false statement, and only seeks to hide the actions that went into the contrived “evidence” that the New York Times presented to the Court.

If shown as such, that same attorney could be facing sanctions.

I suggest that you do more to inform your position than take one side’s statements as gospel. In your earlier comment you stated that “ I am well-versed in Fair Use.”

What ELSE besides the NYT speaking points backs up this statement of yours?

You HAVE to have more, right?

Pro Say

February 27, 2024 08:25 pmI presume you mean this Anon:

https://www.reuters.com/technology/cybersecurity/openai-says-new-york-times-hacked-chatgpt-build-copyright-lawsuit-2024-02-27/

Yet note this:

“OpenAI . . . did not accuse the newspaper of breaking any anti-hacking laws.”

And this:

“What OpenAI bizarrely mischaracterizes as ‘hacking’ is simply using OpenAI’s products to look for evidence that they stole and reproduced The Times’s copyrighted work,” the newspaper’s attorney Ian Crosby said in a statement on Tuesday.”

But in any case, fun times ahead.

Anon

February 27, 2024 08:15 pmIf you are leaning on the New York Times — for anything — you are hopelessly lost.

That is a Woke piece of propaganda trash on par only with WaPo.

Anon

February 27, 2024 03:03 pmPro Say – did you see the new allegations against NYT?

My oh my.

Heard of shooting yourself in the foot? the NYT shoot off both of their legs.

Pro Say

February 27, 2024 02:58 pmAnon — The New York Times IS my thinking. That you believe them to be wrong does not make it so.

We’ll just have to agree to disagree on this one . . . and see what the courts decide. It’s going to be awhile, though; as this case is going to SCOTUS.

Let’s meet back here in 2 – 3 years or so and see who’s right.

In the meantime, don’t take any wooden nickels.

Anon

February 27, 2024 01:32 pmDirecting to a lawsuit from the Times is NOT going to win the day. I have already shared that the Times is going to lose directly on the point of that front end training BEING Fair Use.

Try again – this time use your own thinking.

Pro Say

February 27, 2024 10:16 am“Perhaps you would care to explain why you think this NOT to be Fair Use (and more than merely an exclamation).”

Here you go my friend:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/27/business/media/new-york-times-open-ai-microsoft-lawsuit.html

Anon

February 26, 2024 03:51 pmIt should not befuddle you if you truly knew the parameters of Fair Use.

Plenty of case law on the point that intake to technical transformation process is not something that is a covered right under Copyright.

Perhaps you would care to explain why you think this NOT to be Fair Use (and more than merely an exclamation).

Pro Say

February 26, 2024 11:27 amMy good friend Anon, I am well-versed in Fair Use.

What these companies are doing is Unfair Use. Unfair. Use.

For someone who, like me, strongly supports IP rights, it frankly befuddles the mind to see you support these IP pirates.

And I’m far from alone, as I’m certain that other, equally well-versed IPW readers are equally befuddled.

Anon

February 26, 2024 10:59 amPro Say – “unfettered, illegal, improper”

You are confused as to what is going on.

Maybe you should pause and do some reading on Fair Use.

Pro Say

February 25, 2024 08:48 pmWhile artificial intelligence is certainly artificial, it’s hardly intelligent.

At least sufficiently intelligent to be trusted and relied on.

Will it get better in the future? Sure; as long as the purveyors of this latest “tech-miracle” have unfettered, illegal, improper access to the intellectual property of everyone who has ever lived and who has yet to be born.

No one should be fooled. The fancy-schamancy techno-babble changes nothing.

This is stealing, plain and simple.

It must be stopped.

Anon

February 25, 2024 02:25 pmAnother point:

This statement is unbelievably false, and betrays a bias:

“ but it may become necessary if the courts find that training LLMs on copyrighted material is fair use.”

Why in the world would such a (proper) finding “[make it] necessary” to invoke what it plainly stated to be a messy, imperfect thing when training itself is perfectly legal and cost free?

Anon

February 25, 2024 02:22 pmOr better yet, we can view the (massively – and of necessity) nature of AI processing to easily see that Fair Use applies.

Not the coin toss as portrayed.

Add Comment