“A reviewing court is unable to adequately, reliably, or fairly give deferential review to a district court’s incomplete likelihood of confusion analysis that does not explain its factual findings and legal analysis of all relevant factors.” – Kroger petition

Relish Labs LLC and the Kroger Company (who own the “Home Chef” brand and mark) petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court this week, asking the Justices to review a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit that held Home Chef had not proven consumers were likely to confuse their marks with Grubhub and Takeaway.com’s logo.

Relish Labs LLC and the Kroger Company (who own the “Home Chef” brand and mark) petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court this week, asking the Justices to review a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit that held Home Chef had not proven consumers were likely to confuse their marks with Grubhub and Takeaway.com’s logo.

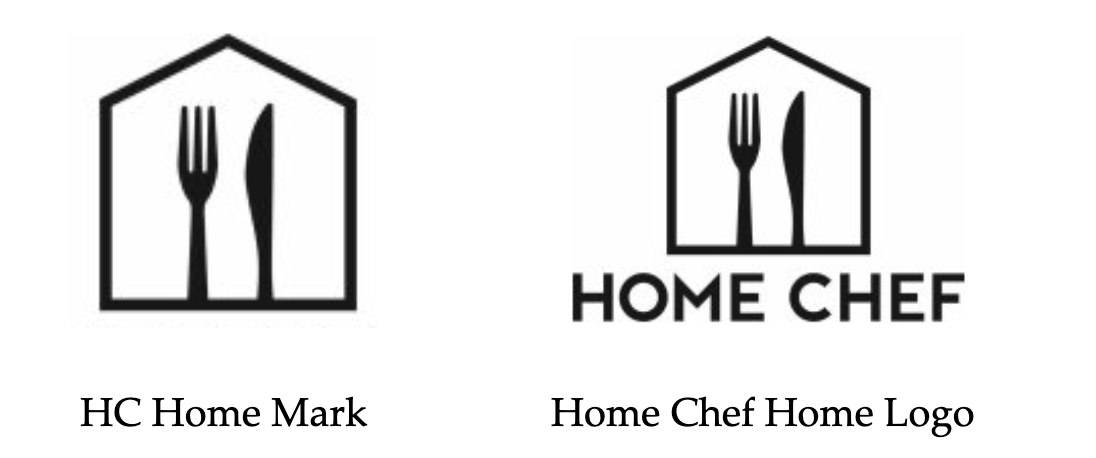

Home Chef is a meal kit company that merged with Kroger in 2018. Kroger operates more than 2,700 supermarkets throughout the United States and offers the Home Chef products in stores, online and through services such as DoorDash and Instacart. Home Chef began using the HC Home Marks in 2014.

Online food delivery company Grubhub was acquired by Just Eat Takeaway (JET) in 2021. JET owns numerous food delivery brands worldwide and combines the Jet House Mark with local brands when conducting business.

Online food delivery company Grubhub was acquired by Just Eat Takeaway (JET) in 2021. JET owns numerous food delivery brands worldwide and combines the Jet House Mark with local brands when conducting business.

When JET filed an international trademark application in 2020, designating the United States as one of the countries it was seeking protection for, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejected the application in a non-final office action, “finding, among other things, that the JET House Mark is ‘highly similar; and ‘confusingly similar’ to the HC Home Mark and Home Chef Home Logo.” The application became abandoned after JET failed to respond to the merits of the non-final office action and then withdrew its application in 2021.

Nonetheless, JET began using the pictured marks following the acquisition of Grubhub in 2021. Home Chef sent a cease-and-desist letter demanding Grubhub stop using any form of the marks and Grubhub subsequently brought suit seeking declaratory judgment that its marks did not infringe. Home Chef then filed a motion for preliminary injunction.

A magistrate judge eventually issued a Report and Recommendation (R&R) finding that the district court should grant the injunction. But the district court rejected the R&R and denied the preliminary injunction, providing an analysis of only three of the likelihood of confusion factors.

A magistrate judge eventually issued a Report and Recommendation (R&R) finding that the district court should grant the injunction. But the district court rejected the R&R and denied the preliminary injunction, providing an analysis of only three of the likelihood of confusion factors.

In its opinion on appeal, the Seventh Circuit reviewed the district court’s judgment for clear error, but addressed one of the likelihood of confusion factors de novo, and concluded overall that it could not say the court clearly erred in its reasoning.

Home Chef’s Supreme Court petition presents the following two questions:

1) Whether the determination of a likelihood of confusion for trademark infringement is a factual finding, reviewable for clear error, or a legal conclusion, reviewable de novo, or a combination?

2) Whether a court should disclose its analysis of all the factors in a multifactor likelihood of confusion balancing determination for trademark infringement?

The petition argues that the district court failed to provide a full analysis of the seven likelihood of confusion factors under Helene Curtis Industries v. Church & Dwight Co., 560 F.2d 1325, 1330 (7th Cir. 1977), addressing only three and relegating the rest to a footnote. The Seventh Circuit then found the district court erred in its analysis of the final factor, intent, but de novo analyzed the “strength of the mark” factor, although the district court had not considered it and the parties had not briefed on it. These differing standards are creating confusion and uncertainty for trademark owners, the petition argues:

“The likelihood of confusion factors are interrelated because the analysis of one can affect another factor’s analysis and weight, which is why a multifactored balancing test was originally deployed…. Due to the factors being interrelated and each bearing on the ultimate question, courts have admonished that each factor should be considered, that all of the factors should be balanced in totality, and that no one factor is dispositive.”

While Home Chef described the magistrate judge’s R&R as providing a “thorough, reasoned analysis,” it is the district court’s decision and not the magistrate’s report, that matter, explains the petition. “A reviewing court is unable to adequately, reliably, or fairly give deferential review to a district court’s incomplete likelihood of confusion analysis that does not explain its factual findings and legal analysis of all relevant factors,” it adds. “It is a subjective, unpredictable, and untenable process.”

Additionally, B & B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc., 575 U.S. 138, 154 (2015) held that, despite the varying multifactor tests used by different circuit courts, the application of the factors must apply the same statutory legal standard for a likelihood of confusion. But the petition cites an empirical analysis of 331 trademark decisions (287 dispositive) from 2006 that concluded “judges employ fast and frugal heuristics to short circuit the multifactor test.” This lack of analysis leads to inconsistency. “Judges assessing consumer confusion from the bench should not stampede over factors which are not even considered,” says the petition.

Furthermore, there is a clear circuit split as to the legal standard used for review of likelihood of confusion cases. The Second Circuit and the Federal Circuit review each factor’s analysis and the overall finding of confusion de novo; the Sixth Circuit reviews each factor’s analysis under the clearly erroneous standard, but the ultimate finding of a likelihood of confusion de novo; the Fourth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits review the analysis of each factor and the ultimate finding under a clearly erroneous standard of review; and the First, Third, Fifth, Eighth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits use the clearly erroneous standard, but analyze the underlying legal principles de novo.

This split leads to unpredictability, as demonstrated in Kroger’s/ Home Chef’s case, where “three sequential decisions analyzed differing combinations of factors and evidence, applying different legal standards,” the petition adds, concluding: “This is the only court which can correct these timeworn inconsistencies.”

Images taken from Seventh Circuit opinion.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Anon

January 15, 2024 01:08 pmThanks IP Nerd for that different perspective.

I would hesitate though on the choice of “that food is practically a universal right,” as US Trademark law is most likely better served without delving into any such context over which a trademark MAY be applied, and stick more to the originating reasons why trademark law was introduced in the first instance.

IP Nerd

January 15, 2024 09:36 amThe GrubHub use of distinctly different color combination, rounded instead of sharp edges on the silverware, and more vivid house design over 5 point geometry like technical design swayed my opinion to let consumers enjoy the benefits of competition. The ultimate deciding factor IMHO is that food is practically a universal right and TM rights infringing of dietary options seems heavy handle for USTPO protection.

Anon

January 13, 2024 11:44 amAs Trademarks are not my forte, a question for those more proficient:

Are not variations such as color, more rounded appearances, and the addition of a chimney the types of typical differentiations on ordinary marks?

I do not believe that the Home Chef folks have any of the special niceties of a Famous Mark designation.