“The Panel’s claim construction so substantially changed the rules of the game as to subvert not only the legitimate investment-backed expectations of petitioner but also the delicate balance between inventors who rely on the law and the public domain.” – Salazar petition

The U.S. Supreme Court today denied a petition that asked it to consider whether the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s (CAFC’s) “construction of petitioner’s patent claim was unforeseeable and unjustifiable under the circuit’s prior decisions,” thereby constituting a judicial taking of property in violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause.

The U.S. Supreme Court today denied a petition that asked it to consider whether the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit’s (CAFC’s) “construction of petitioner’s patent claim was unforeseeable and unjustifiable under the circuit’s prior decisions,” thereby constituting a judicial taking of property in violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause.

The petition was an appeal from the CAFC’s April decision affirming a district court’s judgment that AT&T Mobility LLC did not infringe an inventor’s wireless communications technology patent but also holding that AT&T had forfeited its chance to prove the patent invalid on appeal.

Joe Salazar’s U.S. Patent No. 5,802,467 is titled, “Wireless and Wired Communications, Command, Control and Sensing System for Sound And/or Data Transmission and Reception.” After unsuccessfully suing HTC Corp. for infringement in 2016, Salazar sued HTC’s customers, AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon, in 2019, alleging certain phones sold by the companies infringed his patent. A jury ultimately found that the companies did not infringe but that the patent was not invalid as anticipated.

On appeal, Salazar argued that the district court’s claim construction was erroneous, and he was therefore entitled to a new jury trial. Specifically, Salazar said that the court’s construction of “a” microprocessor and “said” microprocessor was incorrect and that the claim terms should have been interpreted “to require one or more microprocessors, any one of which may be capable of performing each of the ‘generating,’ ‘creating,’ and ‘retrieving’ functions recited in the claims.” The district court had construed the claim to mean that, while “the term ‘a microprocessor’ does not require there be only one microprocessor, the subsequent limitations referring back to ‘said microprocessor’ require that at least one microprocessor be capable of performing each of the claimed functions.” The CAFC agreed.

Citing cases such as Baldwin Graphic Sys., Inc. v. Siebert, Inc.; Harari v. Lee; Convolve, Inc. v. Compaq Computer Corp.; and In re Varma, the CAFC explained that its precedent supports this reading of the claim terms. “Like the claim language in Convolve and Varma, the claim language here requires a singular element—’a microprocessor’—to be capable of performing all of the recited functionality,” wrote the appellate court.

In his September petition to the Supreme Court, Salazar said this decision was a misapplication of “well-settled rules of claim construction, resulting in a drastic, unforeseeable narrowing of petitioner’s patent claims, such that petitioner’s ‘present invention’ as described in the patent falls outside the scope of the patent’s protection.” Specifically, “…petitioner had a reasonable expectation that his patent claims would be interpreted to include one or more microprocessors, any one of which could perform any of the recited functionality,” said the petition. Both the “present invention” description and embodiments of the ‘467 patent refer to multiple microprocessors, said Salazar. And since he could not have anticipated the decision based on prior CAFC case law, the ruling represents a judicial taking, said the petition.

Ultimately, the petition argued that the risk of upsetting the delicate balance between inventors and the public with respect to patent law warranted review:

“The Panel’s claim construction so substantially changed the rules of the game as to subvert not only the legitimate investment-backed expectations of petitioner but also the delicate balance between inventors who rely on the law and the public domain. And this erroneous claim construction constitutes grounds for granting a partial new trial on infringement. Network-1 Techs., Inc. v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 981 F.3d 1015, 1022 (Fed. Cir. 2020).”

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

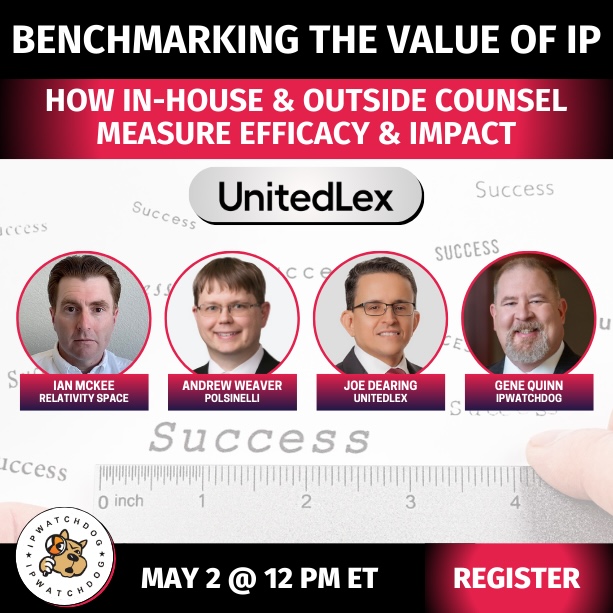

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Alan

November 23, 2023 03:23 pmUnder the facts of this case, this is not a judicial taking on any level. The ‘467 patent refers to the microprocessor over 200 times (if you include the claims) and does not disclose any embodiment in which more than one microprocessor is used. There is no statement that one or more (micro)processors can be used in the patent. There is no statement that “a” means one or more.

At one level, Salazar got a generous claim construction where “a” processor could mean one or more processors (when such is not disclosed in the patent or drawings). To complain that a claim to “a” processor and “said” processor should cover multiple processors doing individual functions when there is not anything remotely close to this disclosed in the patent is simply wrong. The district court correctly ruled against Salazar and the CAFC correctly affirmed.

There are many, many cases the CAFC gets wrong, but this is not one of them.

Anon

November 21, 2023 11:55 amYet another indicator that Congress should seriously consider exercising its Constitutional authority of jurisdiction stripping of non-original jurisdiction of patent cases away from the Supreme Court (along with my usual caveats that AN Article III Court must still be involved to satisfy Marbury AND that the current Article III Court of the CAFC must be reset from its current simian-firehosed-in-a-cage anti-patent tendencies.