“The right-to-repair movement isn’t based on a preexisting right; it’s instead asking lawmakers to create a new right at the expense of the existing rights of IP owners.” – Devlin Hartline

The House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet met today to hear from a number of witnesses about the intersection of intellectual property rights and consumers’ right to repair products they own.

The House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet met today to hear from a number of witnesses about the intersection of intellectual property rights and consumers’ right to repair products they own.

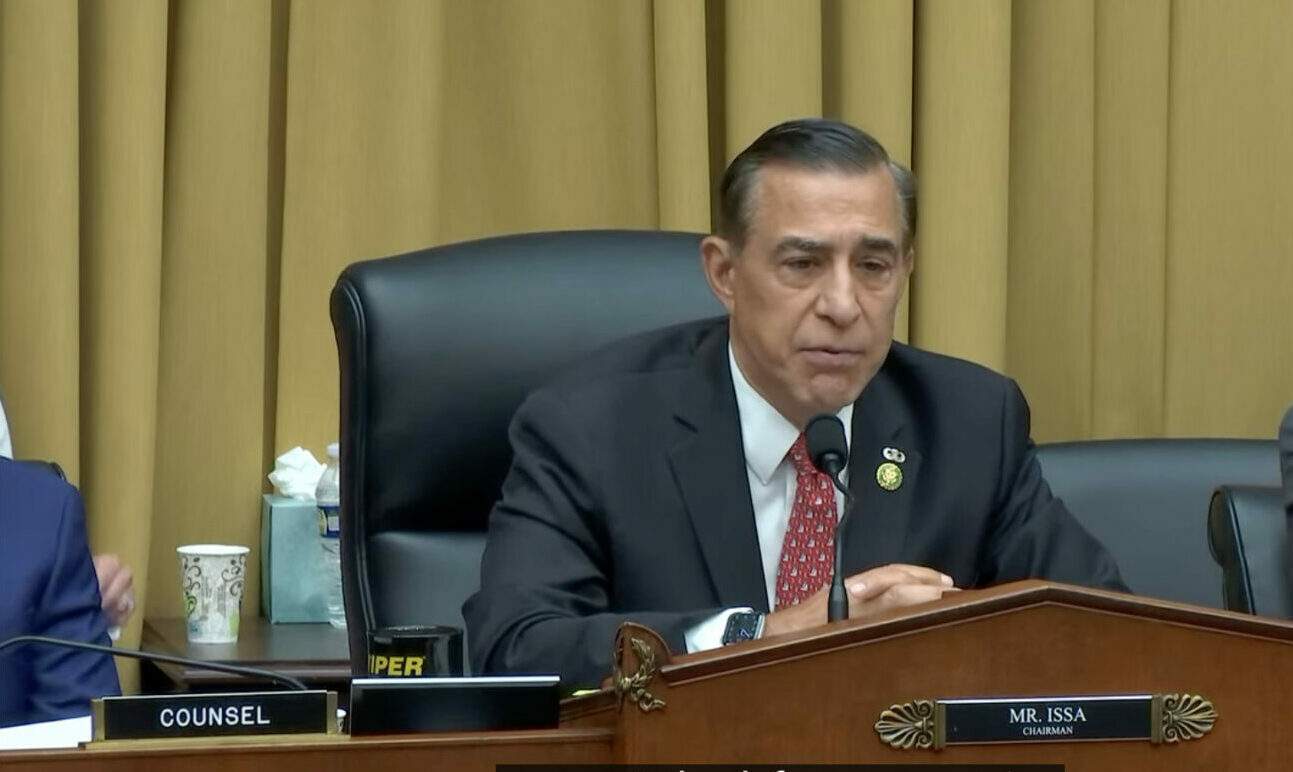

The concerns voiced by witnesses and congress members today centered around harm and cost to consumers as a result of technological protection measures (TPMs) and increased use of IP tools such as design patents to thwart competition for after-market parts. Subcommittee Chair Darrell Issa (R-CA) floated the idea of a “standard essential copyright” regime that would require companies to make the proprietary information necessary for repairs available for use, presumably via compulsory licensing schemes and/or under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

Issa introduced The SMART Act in March, which proposes amending U.S. design patent law to reduce from 14 years to 2.5 years the time car manufacturers can enforce design patents on collision repair parts, such as fenders, quarter panels and doors, against alternative parts suppliers. A bipartisan group of five other congress members joined him as cosponsors.

Harm to Consumers

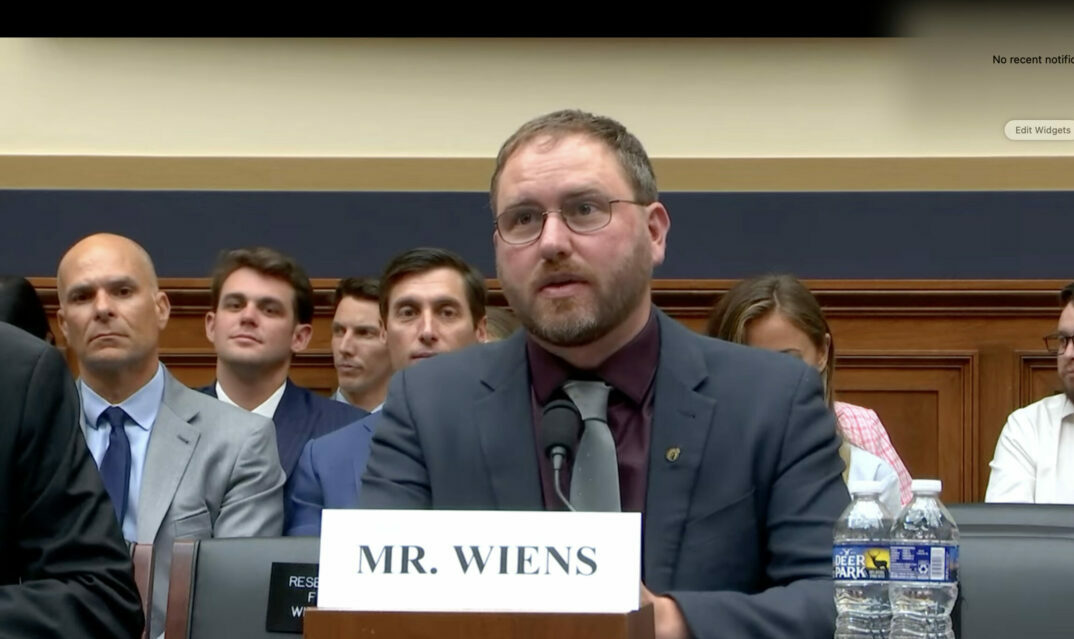

Kyle Wiens, Co-founder and CEO of iFixit, shared the perspective of consumers in today’s hearing, who he said are being stymied from repairing their own property by large companies that are using legal mechanisms to drive up costs. In some cases, said Wiens, these tactics are creating problems that could have a broader impact, such as in the agricultural sector. Wiens said he has a friend whose John Deere tractor he can’t fix, for instance, because it requires a part Wiens is not legally allowed to make or repair. As a result, the farmer had to rent an expensive tractor for a week while he waited for the repair. If this happened in the growing season, it could have much broader implications, another witness commented later in the hearing.

Kyle Wiens, Co-founder and CEO of iFixit, shared the perspective of consumers in today’s hearing, who he said are being stymied from repairing their own property by large companies that are using legal mechanisms to drive up costs. In some cases, said Wiens, these tactics are creating problems that could have a broader impact, such as in the agricultural sector. Wiens said he has a friend whose John Deere tractor he can’t fix, for instance, because it requires a part Wiens is not legally allowed to make or repair. As a result, the farmer had to rent an expensive tractor for a week while he waited for the repair. If this happened in the growing season, it could have much broader implications, another witness commented later in the hearing.

Wiens said he got started in his career by attempting to fix his own computer, only to find the user manual didn’t exist online because Apple had sent DMCA takedown requests to every website that posted it. Issa and others later in the panel questioned whether user manuals should even be copyrightable.

There is No Right-to-Repair

The sole pro-IP perspective on the witness panel was Devlin Hartline, Legal Fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Forum for Intellectual Property. Hartline said there simply isn’t a right to repair in existing law, and that it is IP rights that ultimately protect the public good.

“The right-to-repair movement isn’t based on a preexisting right; it’s instead asking lawmakers to create a new right at the expense of the existing rights of IP owners,” Hartline explained.

He said Issa’s bill, as well as the Freedom to Repair Act, would simply rewrite the Copyright or Patent Act, while other bills (the REPAIR Act and Fair Repair Act) take the approach of defining “the normal exercise of IP rights as an unfair or deceptive practice to be enforced by the [Federal Trade Commission] FTC.” However, the FTC already has this authority, Hartline said, and has failed to bring any such enforcement actions. The reason for that is because IP owners are merely exercising their IP rights and it is not an anti-competitive practice, he claimed, adding: “As tempting as it may be to take away or limit IP rights so others can copy and then call that competition, I would urge the members to think about whether that truly represents sound economic policy.”

Security Concerns and Unintended Consequences

While those in favor of right-to-repair changes, including Issa, conceded that safety concerns about after-market parts, particularly in sectors such as automobiles and medical devices, have to be factored in, some downplayed those concerns, noting that authorized manufacturers often fail when it comes to safety as well. Aaron Perzanowski, Thomas W. Lacchia Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School, cited a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report that he said showed independent repair of medical devices was safe and effective. Perzanowski said that IP law isn’t the right tool to ensure safety in any case, and at the end of the day, the bad actors already have the tools in question.

While those in favor of right-to-repair changes, including Issa, conceded that safety concerns about after-market parts, particularly in sectors such as automobiles and medical devices, have to be factored in, some downplayed those concerns, noting that authorized manufacturers often fail when it comes to safety as well. Aaron Perzanowski, Thomas W. Lacchia Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School, cited a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report that he said showed independent repair of medical devices was safe and effective. Perzanowski said that IP law isn’t the right tool to ensure safety in any case, and at the end of the day, the bad actors already have the tools in question.

Pressed by Rep. Ben Cline (R-VA) about risks such as China gaining access to this information if opened up, Perzanowski said they already have it. “We’re trying to get very targeted tools in the hands of consumers to fix the gifts they buy their kids for Christmas,” Perzanowski said.

Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), who took part in the negotiations to pass the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), said “the process didn’t really work as we intended,” as Congress didn’t create the DMCA provisions barring circumvention of TPMs “so monopolies could control products.”

Lofgren explained that TPMs were enacted to protect against hacks of copyrighted content but that there was no consensus about what exceptions there should be, so the compromise was to have the Copyright Office regularly revisit and assess appropriate exemptions via rulemaking. Section 1201(a)(1) of the DMCA thus requires the Librarian of Congress, via rulemaking, “to exempt any class from the [TPM] prohibition for a three-year period if she has determined that noninfringing uses by persons who are users of copyrighted works in that class are, or are likely to be, adversely affected by the prohibition against circumvention during that period.”

While the Office has said in these rules that engaging in circumvention for purposes of repair is perfectly lawful for consumers, there are often additional tools needed to make a repair that are not covered by the exemptions.

Paul Roberts, Founder, SecuRepairs.org; Founder and Editor-in-Chief, the Security Ledger, also testified that “fair right-to-repair laws don’t threaten cybersecurity.” Roberts said there is no evidence that the types of information covered by right-to-repair pose any cybersecurity threat beyond the security weaknesses that are already inherent to internet of things (IoT) devices. Roberts called IoT security weakness “an epidemic,” citing statistics that show 68% of IoT devices contained high risk or high vulnerability. In one example, web hackers exposed wide ranging and exploitable flaws in vehicle telematics systems from 16 different auto makers that allowed researchers full access to a company-wide administration panel that allowed them to send arbitrary commands to 15.5 million vehicles, including first responder vehicles. “Hacks like this take place without any access to repair materials,” Roberts said.

Industry Solutions

This year, two memorandums of understanding (MOUs) were signed regarding the right-to-repair debate. John Deere and the American Farm Bureau signed an agreement in January and this month several trade organizations struck a deal with the auto industry. But many right-to-repair activists say such deals don’t go far enough. However, Scott Benavidez, Chairman, Automotive Service Association and Owner, Mr. B’s Paint & Body Shop, testified that the auto MOU has solved their problems for now, though concerns for the future remain as technology continues to evolve and become more complex.

What is Copyright, Even?

At the close of the hearing, Issa challenged Hartline on the very premise of copyright law. Issa said: “Copyright is not a right to exclude, as you know; for the most part with copyright you get a reasonable fee or license; if I have a piece of music, I don’t inherently have the ability to stop people from performing and the like.” Hartline disagreed, responding that “copyright is a right to exclude.”

At the close of the hearing, Issa challenged Hartline on the very premise of copyright law. Issa said: “Copyright is not a right to exclude, as you know; for the most part with copyright you get a reasonable fee or license; if I have a piece of music, I don’t inherently have the ability to stop people from performing and the like.” Hartline disagreed, responding that “copyright is a right to exclude.”

In response to another question from Issa asking how Hartline would reconcile an example in which IBM buys its own used parts back, but opposes allowing the same company to sell to other companies, Hartline said, while not familiar with the IBM story, “it sounds like you have someone who has IP protection.” He added:

“And what do they get, a right to exclude. They can use that right to create business relationships and increase profits, which they in turn use on R&D, and we in turn get more innovation.”

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Anon

July 19, 2023 06:10 pmI would add to Mr. Hodges’ comment in that “right” is in fact one of the inalienable rights of “property” as reflected in the doctrines of exhaustion.

This (sadly) is more than a little bit reflected in the Sprint Left (and Uber elitist Rules for Thee) notions of “you will own nothing and like it.”

Bob Hodges

July 19, 2023 02:26 pmThe right to repair inherently existed for all time before copyright law, and for the entire time toward the present, until (1) technology became sufficiently complex to allow locking purchasers out the ability to repair and (2) lawyers starting to think up ways to pervert copyright law to make it a violation of copyright to get or use the information, tools. and parts needed to repair the a consumer’s property.

So, right to repair co-existed with copyright until very recently.

Anon

July 18, 2023 06:31 pmOnly caught bits and pieces.

Thank you for the summary.