“If a patent system is structured such that the judicial branch can retroactively presume that one-third of patents protecting the top pharmaceuticals are invalid, inventors and companies may struggle to believe that the quid pro quo provided by the system is not a scam.”

Case law has defined prosecution laches as an affirmative defense against an infringement assertion. Specifically, the case law indicates a patent that is being asserted is unenforceable when the patentee caused an unreasonable and unexplained delay in prosecution of the patent. Symbol Tech v Lemelson Medical, No. 04-1451 (Fed. Cir. 2005). There is relatively little case law on the specifics of laches. However, in 2021, the Federal Circuit said: “we now hold that, in the context of a § 145 action, the PTO must generally prove intervening rights to establish prejudice, but an unreasonable and unexplained prosecution delay of six years or more raises a presumption of prejudice”. Gil Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021). What does this – or might this – mean beyond the Hyatt case?

Case law has defined prosecution laches as an affirmative defense against an infringement assertion. Specifically, the case law indicates a patent that is being asserted is unenforceable when the patentee caused an unreasonable and unexplained delay in prosecution of the patent. Symbol Tech v Lemelson Medical, No. 04-1451 (Fed. Cir. 2005). There is relatively little case law on the specifics of laches. However, in 2021, the Federal Circuit said: “we now hold that, in the context of a § 145 action, the PTO must generally prove intervening rights to establish prejudice, but an unreasonable and unexplained prosecution delay of six years or more raises a presumption of prejudice”. Gil Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021). What does this – or might this – mean beyond the Hyatt case?

The pharmaceutical area may provide an insightful perspective on the potential reach of this dicta, given that pharmaceutical patents are frequently relied upon to at least partly justify billions of dollars of investment for research and development. Therefore, this study investigates patents that were listed in the Orange Book or Purple Book as protecting the top 20 pharmaceuticals, in terms of revenue.

Drilling Down on the Data

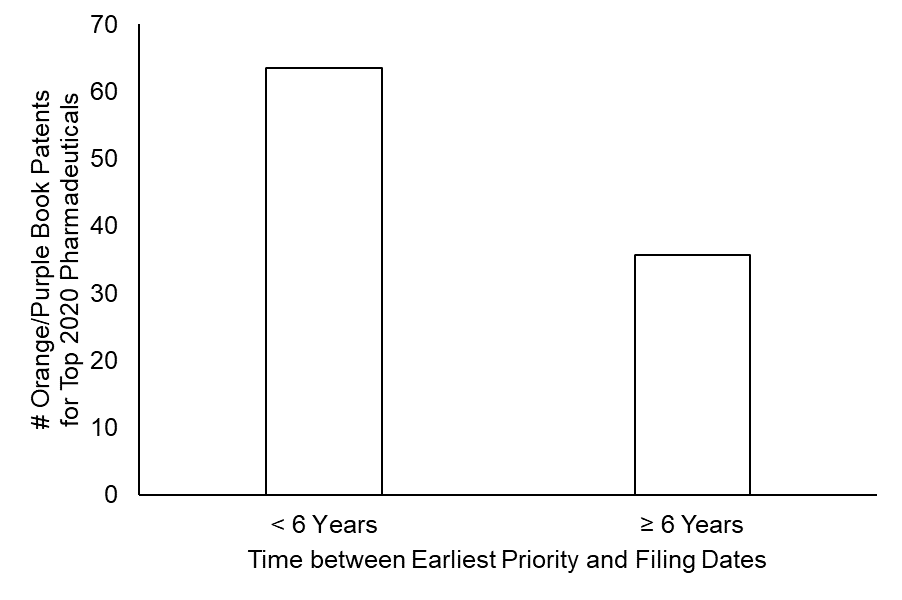

More specifically, the 20 pharmaceuticals with the highest 2020 revenues were studied. For each of these drugs, IPDataLab identified each patent listed in the Orange Book (which includes information about approved small-molecule therapeutics) or the Purple Book (which includes information about approved biologic therapeutics) that had been identified by the pharmaceutical company as protecting the drug. For each patent application, the earliest priority date and the application’s filing data were also identified to determine the time difference between the priority date and the application’s filing date.

As shown in FIG. 1, over one-third of the patents (87 out of 244) that were identified as protecting the top-revenue pharmaceuticals had a delay of over six years between an earliest priority date and the application filing date.

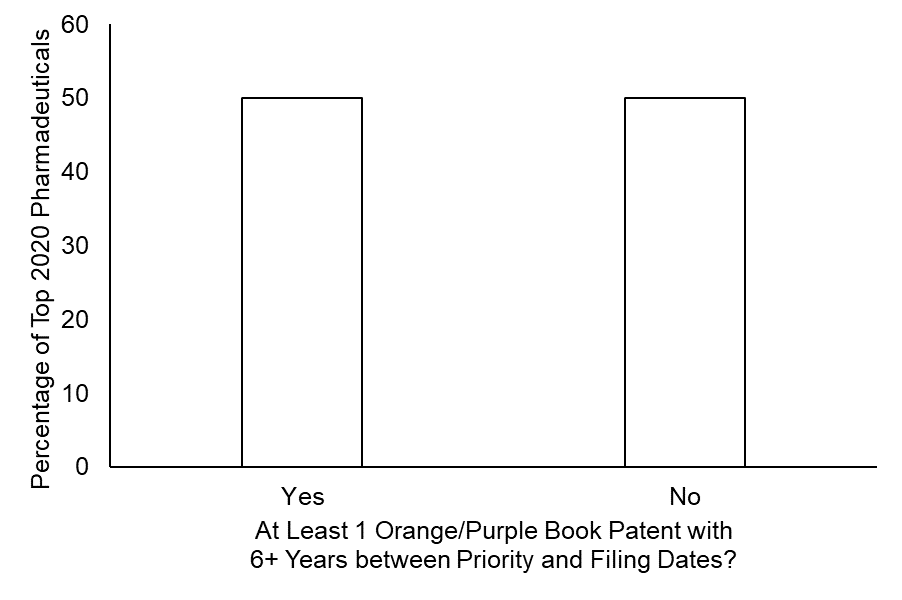

Notably, the size and temporal profile of patent portfolios did vary across these pharmaceuticals. However, of the pharmaceuticals with the highest 2020 revenue, 50% of these top pharmaceuticals had at least one patent listed in the Orange Book or Purple that – according to the dicta in the Hyatt case would be presumed to be invalid. (See FIG. 2.)

Anti-Innovation Implications

Recall that the Federal Circuit’s analysis of laches in Hyatt is tied to a “presumption of prejudice”. This analysis concentrates on whether there would be prejudice against the public, but particularly when an invalidity avenue is being defined by judges and not the legislative branch, it is important to also consider the potential impacts to the patent owner and overall fairness and societal efficiency.

From the patent owner’s perspective, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) fees (and likely attorney fees) were paid with the expectation that – if a patent application is allowed and complies with the statutory patent requirements –it will lead to a valid and enforceable patent. If a patent system is instead structured such that the judicial branch can retroactively presume that one-third of patents protecting the top pharmaceuticals are invalid, inventors and companies may struggle to believe that the quid pro quo provided by the system is not a scam and/or that an investment in researching and developing a product is a sound business decision.

Further, consider the approval timeline for a pharmaceutical. An entity may discover that a particular small- or large-molecule drug shows promise for effectively treating a medical condition, and they may quickly file a patent application. However, then years of clinical trials are performed to ensure that the drug truly does effectively treat the condition, that any side effects are not so severe and/or common to outweigh the drug’s benefit, to identify appropriate patient groups, to identify specific dosages, etc. Subsequently, or in the meantime, the entity may submit and pursue an application to the Food and Drug Administration to request approval of the drug. In the vast majority of instances, a promising pharmaceutical candidate is dropped in response to sub-optimal experimental or trial data. The Federal Circuit’s proposed presumption of prejudice if there is a more than six-year delay between a priority date and a filing date may put the entity in a position of having to choose between initially investing even more money in each pharmaceutical candidate for patent protection (even though the vast majority of drug candidates fail) or potentially being in a position where the patent protection for a highly valuable pharmaceutical is weak. Thus, the laches presumption sets up a situation that promotes even larger investments in research efforts that are statistically very expensive and very likely to fail.

Thus, in sum, the Federal Circuit’s presumption of laches applying with an application that is filed more than six years after a priority date would have a large impact on existing pharmaceutical patents. Judicially creating new invalidity presumptions that apply retroactively is a very risky move, as courtrooms are not set up to ensure that diverse interests are well represented or that the potentially chilling effects are thoroughly considered.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 204633772

Author: Alexis84

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Julie Burke

February 9, 2023 11:34 amDelving deeper, the common denominator between Hyatt’s patent applications and top pharmaceutical patent applications: all were susceptible to being flagged by the USPTO for extra scrutiny under the SAWS program.

The USPTO used the SAWS program to specifically target applications which contained broad claims directed to pioneering inventions. In TC1600, the SAWS memo also instructed examiners and SPEs to target applications directed to drugs and methods of treatments for diseases that USPTO management considered as having no known cure – diseases such as AIDS/HIV, Alzheimers, ALS, certain types of cancers, mental retardation, personalized medicine methods directed to patient’s specific race or ethnicity, the list goes on and on.

Moreover, patent applications whose issuance would result in unwanted* news coverage — a patent on a pioneering cancer treatment! a vaccine for coronaviruses! — were also flagged for SAWS review.

*Patent Office upper management traditionally considers any type of news coverage as unwanted. Kudos, Gene Quinn, for continuing to provide shine that bright flashlight on the USPTO’s shenanigans.

The SAWS flag itself, hidden behind the scenes in the electronic file wrapper, was particularly sticky. It could only be seen, added or removed by a specially designated SAWS POCs who selected specific cases for extra scrutiny. Applicants could not escape SAWS scrutiny by filing a CON or DIV, since these too (and potentially anything filed by a SAWS-flagged inventor) would likely be flagged for SAWS review.

Once an application was flagged for SAWS review, it was removed from the normal prosecution pipeline and subject to additional reviews, typically resulting in further delays and denials. These years-long delays became themselves a catch-22 kiss-of-death since long pendency itself was an additional reason why an application remained on the SAWS list. In essence, under the guise of SAWS, the USPTO created a panel of long delayed (submarine type) patents, including their CONs and DIVs, in the pharmaceutical and other areas and subjected these cases to disparate treatment.

Note that SAWS program delays ran counter to MPEP 707.02, which instruct SPEs to expedite review of patent applications pending five or more years.

If the application survived the SAWS gauntlet and eventually issued, (many did issue with narrower, delayed claims), the long delays could be viewed as beneficial by drug companies resulting in valuable PTA/PTE. Now, relying on Kate Guadry’s cautions above, could the SAWS delays leave a patent owner open to the presumption of laches?

Mr. Hyatt’s cases are unusual in the fact that the USPTO records obtained during discovery proceedings clearly show delays and denials due to the SAWS program. Most patent applicants are not privy to this information.

Mr. Hyatt’s situation should be illuminating to all — via the SAWS program, the USPTO applied homegrown procedural mechanisms they developed and honed for the Hyatt applications to other applications claiming pioneering, news worthy inventions.

Because the USPTO has not disclosed which applications were initially subject to SAWS delays/denials and which resulting CONs and DIVs were additionally flagged, pharmaceutical patent owners and their competitors generally cannot ascertain if a particular patent’s long pendency was ultimately attributable to USPTO’s actions under the SAWS program.

St. John Mountbatten

February 7, 2023 02:51 pmTwo brief responses:

(1) This is a small point, but a finding of prosecution laches renders the patent unenforceable, not invalid. The nice thing about an enforceability defect compared to a validity defect is that some enforceability defects can be cured.

(2) The test for prosecution laches has two prongs: (a) unreasonable delay; and (b) prejudice. In other words, a presumption of prejudice is not ipso facto a presumption of unenforceability. There is a whole other prong of the test that the proponent of unenforceability must prove, even if they rely on the presumption of prejudice.

B

February 7, 2023 11:19 am@ Curious “Only if the Federal Circuit ignores the very fact specific situations (and exceptionally extreme facts) associated with the Hyatt applications and explicitly identified in the decision and ignores them all.”

The Fed Cir ignore facts?

Naw

Curious

February 6, 2023 10:08 pmDoes Hyatt v. Hirshfeld Mean That More than One-Third of Patents on the Top Pharmaceuticals are Presumed Invalid?

Only if the Federal Circuit ignores the very fact specific situations (and exceptionally extreme facts) associated with the Hyatt applications and explicitly identified in the decision and ignores them all.

Hyatt, for better or worse, has attempted to game the system to the nth degree. It was only a matter of time before the USPTO/Federal Circuit was going to push back. I can only hope that they didn’t make bad law in doing so.

A good attorney should be able to distinguish whatever fact pattern they are dealing with from the fact pattern of Hyatt.

Anon

February 6, 2023 05:21 pm“ Further, consider the approval timeline for a pharmaceutical. An entity may discover that a particular small- or large-molecule drug shows promise for effectively treating a medical condition, and they may quickly file a patent application. However, then years of clinical trials are performed to ensure that the drug truly does effectively treat…”

The problem (this problem) has been identified before — by me — and is better phrased under the law at 35 USC 101 in that utility is required to be present AT filing.

Patent filings have never been intended to be “research plans,” and the early filings at even a hint of utility violate the requirement that Actual utility (reflected in the claims) must be present at time of filing.

When this trove (1/3 would seem likely to be a LOW estimate) actually fail later to have that utility, this speaks to a systemic abuse of the patent process.

The excuses of “but this is for human health,” and “but it costs so much” simply are not a part of patent law — which is most all agnostic to the area of innovation.