“The Federal Circuit held that the USPTO sufficiently fulfilled its burden of proof and that the burden now shifts to Hyatt to show that he had not engaged in unreasonable and unexplainable delay…. The author believes that it will be important for subsequent decisions in this family to be handled carefully so as to not inadvertently risk the potential for this defense to be applicable to common situations.”

Gilbert Hyatt

Gilbert Hyatt was one of many applicants who filed many patent applications shortly before the June 8, 1995 transition point, where patent terms transitioned from being defined based on 17 years from issuance to 20 years from filing. However, he was quite unique in that he was an independent inventor who filed 400 patent applications before this transition point. The vast majority of these applications are still pending – decades after filing. Hyatt asserts that the long pendency is due to bad-faith behavior of the USPTO, while the USPTO asserts that the extended pendency is due to inaction by Hyatt and the complexity of the applications.

At this point, there are multiple ongoing litigations between Hyatt and the USPTO. The Federal Circuit issued a decision for one of these litigations on June 1, 2021: Gil Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021). Hyatt had filed the underlying complaint under 35 U.S.C. 145, in response to decisions issued by the Patent and Trial Appeal Board (PTAB) against four particular patent applications. Summary judgment was denied.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) had then moved to dismiss the actions for prosecution laches. Specifically, the USPTO asserted that the patent applicant’s “conduct in … [prosecuting his applications was] unreasonable, inexcusable, and warrants dismissal of his pending claims under the equitable doctrine of prosecution laches”. The USPTO contended that the priority chains (that claimed priority to many applications, some of which were filed decades earlier), shifting claim scopes, duplicity across claims, the length of the applications, and a lack of having a “master plan” for amending all of his patent applications (which had only 11 unique specifications) supported their position.

Meanwhile, Hyatt has pointed to his timely filing of responses and to USPTO delays as exemplifying why he believes that the USPTO is to blame for the extended prosecution of his patent applications. For example, the district court made note of 80 of Hyatt’s applications that were “held by PTO in a proverbial Never-Never Land” between 2003 and 2012, where Examiners’ Answers were never filed [after Appeal Briefs had been filed]. Thus, the appeals and examination were both completely stalled.

Prosecution Laches

Rarely do patent attorneys need to think about “prosecution laches”. Prosecution laches “applies only in egregious cases of unreasonable and unexplained delay in prosecution”, though “there are no firm guidelines for determining when prosecution laches is triggered”. Laches does not apply in response merely to passage of an extended period of time (e.g., even 24 years between applicant filing and patent issuance). In cases where patent laches is deemed to have applied, the patent is invalid.

The USPTO had never before asserted a prosecution laches defense in a district court case; that defense instead had been solely used to invalidate issued patents (not to preclude issuance of patent applications). Nonetheless, the Federal Circuit held that the USPTO has the right to assert the defense of prosecution laches in a civil action to obtain a patent under 35 U.S.C. 145. The court reasoned that this conclusion was consistent with the agency’s ability to use prosecution laches to reject a patent application and further is in the interest of the public by providing consistent standards across examination and validity processes.

Importantly, the USPTO and Hyatt took different positions as to what types of conduct were relevant to determining whether prosecution laches applies. Specifically, the Federal Circuit has held that the totality of circumstances (including conduct identified in the prosecution of related patents and overall delay) may trigger patent laches. The USPTO contended that this means that Hyatt’s actions, as they pertain to his entire portfolio, should be considered when determining whether prosecution laches applies. Hyatt asserted that his conduct during prosecution of the four applications at issue in the subject case is all that is pertinent and that prosecution actions across his portfolio are not legally relevant in terms of whether prosecution laches should apply to the cases at hand. For example, Hyatt notes that an alternative approach would lead to needing to consider prosecution actions that post-date even the initiation of the subject litigation.

Prosecution of the Four Applications at Issue

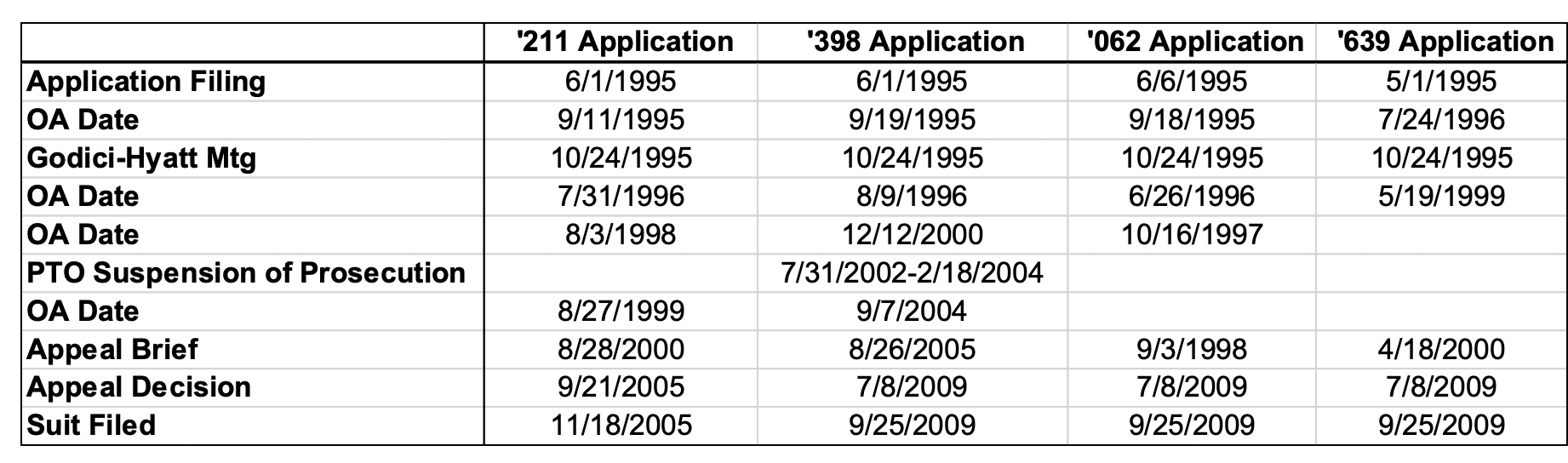

The Table below shows significant prosecution dates for the four patent applications pertaining to the Complaint underlying the Gil Hyatt v. Hirshfeld (Fed. Cir. 2021) decision. Hyatt contends that the only unreasonable delays were those of the USPTO.

In general, the prosecution dates may seem unremarkable before the 2002 USPTO suspension of prosecution. However, the October 24, 1995 meeting between the applicant USPTO Group Director (Nicholas Godici) is atypical. During the (informal) meeting, Hyatt agreed to “focus” the claims in his applications to better distinguish the applications, though he later admitted that he did not have a “master plan” for any such claim amendments. Neither party memorialized the meeting, and substantive examination of Hyatt’s patent applications proceeded despite the lack of Hyatt not having and not implementing any master plan.

District Court Decision

The district court held that the record did not show any unreasonable delay by Hyatt in prosecuting the four patent applications. Further, the district court concluded that any non?action of Hyatt responsive to this meeting was insufficient to qualify for prosecution laches. Rather, it was held that although Hyatt “‘could have’ been more helpful …, there is no abstract requirement for a citizen to tailor his conduct in pursuit of his constitutional right to a patent, to conform to what is ‘feasible’ for the agency”. Finally, the district court rejected arguments by the USPTO that Hyatt’s conduct in prosecuting other applications in his portfolio be considered when determining whether patent laches apply to the civil action under 35 U.S.C. 145 that pertained to four specific applications.

Where to Look – the Specific Applications or the Portfolio?

The Federal Circuit held that the district court refused or discounted evidence that was relevant to assess the totality of circumstances that inform whether prosecution laches apply. Specifically, the Federal Circuit held that it was improper for the district court to have discounted or not considered:

- Hyatt’s alleged “pattern of rewriting or shifting claims midway through prosecution in applications other than the four at issue … because the claim shifting ‘long postdated the close of prosecution’ of the four applications at issue here.” (Emphasis added.)

- Hyatt’s “pattern of prosecution conduct after 2012”, explaining that these prosecution history following the onset of litigation in these matters and that the prosecution histories of the applications at issue ended in 2002.

- Hyatt’s informal agreement with Director Godici.

- The fact that the USPTO has spent more than $10 million administering Hyatt’s applications, while Hyatt has spent only approximately $7 million in fees.

- The fact that four claims of Hyatt’s have lost in interference proceeding in view of the fact that Hyatt’s portfolio included approximately 115,000 claims.

The Federal Circuit thus held that the district court failed to consider evidence that had the potential to show a “pattern of conduct across an enormous body of similar applications”.

Who to Look At – Both Parties or Only the Patent Applicant?

Delay caused by the USPTO does not excuse a patent applicant’s delay for the purposes of prosecution laches. The Federal Circuit held that the district court “gave lip service to this principle [but] effectively used the ‘totality of the circumstances’ standard as a vehicle for blaming the PTO for the prosecution delays”. The Federal Circuit noted that the district court faulted the USPTO for the way that the agency examined Hyatt’s applications and for its suspensions of action and that the district court also emphasized that applicant have broad latitude in prosecuting their applications.

Meanwhile, the Federal Circuit held that the patent statutes and regulations are not the only limit on how an applicant cannot prosecute patent applications. Rather, the Federal Circuit held that prosecution laches require that the applicant prosecute applications in “an equitable way that avoids unreasonable, unexplained delay that prejudices others”.

While the Federal Circuit reemphasized its holding from Bogese, 303 F.3d at 1362 that any USPTO delay (while it can be considered in the totality of circumstances) cannot excuse an applicant’s delay. Interestingly, the Federal Circuit reasoned: “Indeed, the patent statute already deals with delay by the PTO when it provides for patent term adjustment to account for that delay. See 35 U.S.C. § 154(b) …. The PTO’s delay therefore provides a weak reason to negate prosecution laches.” (The author finds this analysis to be faulty, in that patent term adjustment does not apply to pre-GATT filings.)

Thus, while the “totality of circumstances” approach for assessing prosecution laches can result in considering the actions of the USPTO, it held that the district court overemphasized the USPTO’s actions and inactions and excused Hyatt’s prosecution conduct.

Burden Shift to Hyatt to Explain “Delays”

The Federal Circuit turned to the specific facts of the record to assess whether the evidence and arguments were sufficient to shift the burden to Hyatt (to demonstrate that there was not unreasonable and inexplicable applicant delay). The Federal Circuit made note of the following circumstances:

- Hyatt filed hundreds of applications in 1995. Each application included one of eleven specifications from an earlier parent application. Each application include “a small set of claims, many of which were identical to each other”. The Federal Circuit characterized these applications as “placeholders”. Since filing, Hyatt has expanded the claim sets to include an average of 300 per application. Because many of the parent applications for these filing dates that were in the 1970s and 1980s, the Federal Circuit held that the “magnitude of Hyatt’s delay in presenting his claims for prosecution suffices to invoke prosecution laches”.

- Many of the applications claim priority to a large number of applications, which “frustrated the examiners’ ability to take the preliminary step of identifying the relevant body of prior art”.

- The patent applications were characterized as being long and complex.

- Hyatt amended claim sets to include hundreds of claims. (The author is unsure as to whether these hundreds of claims were filed before or after examination commenced.) Many claims were characterized as being “identical or patentably indistinct claims across industries”.

- Hyatt engaged “in a pattern of rewriting claims entirely or in significant part midway through prosecution, thereby, again, restarting examination”.

The Federal Circuit concluded that Hyatt’s prosecution techniques were “unique” and “overwhelmed the PTO”. Thus, the Federal Circuit held that the USPTO sufficiently fulfilled its burden of proof and that the burden now shifts to Hyatt to show that he had not engaged in unreasonable and unexplainable delay.

Prejudice – New Threshold for Section 145 Actions and Laches

The existing case law required that prejudice be shown for prosecution laches to apply. The Federal Circuit decision stated: “we now hold that, in the context of a § 145 action, the PTO must generally prove intervening rights to establish prejudice, but an unreasonable and unexplained prosecution delay of six years or more raises a presumption of prejudice”. Thus, the court concluded that the USPTO sufficiently demonstrated prejudice and the burden shifts to Hyatt to prove lack of prejudice.

Remand

The Federal Circuit remanded the case to the district court for the presentation of evidence pertaining to prosecution laches. The Federal Circuit made a note that merely meeting statutory requirements – without more – is insufficient to demonstrate that Hyatt’s delay was unreasonable and unexplained. Rather, the Federal Circuit is requiring Hyatt to demonstrate a legitimate, affirmative reason that would “excuse [him] from responsibility for the sizable undue administrative burden that his applications have placed on the PTO”. The Federal Circuit more specifically required that any justification for Hyatt to have “ignore[d] Director Godici’s instruction to demarcate his applications in 1995; justify his decision to adopt the specific prosecution approach that he did—unique in its scope and nature—as detailed in the PTO’s Requirements; and justify his failure to develop a plan for demarcating his applications over at least the 20 year period from 1995 to 2015”.

Author’s Final Thoughts

Hyatt’s patent portfolio and prosecution experience are certainly unique (though the author has not reviewed any of Hyatt’s prosecution records). However, prosecution laches has a very extreme consequence of patent invalidity. The author believes that it will be important for subsequent decisions in this family to be handled carefully so as to not inadvertently risk the potential for this defense to be applicable to common situations, such as those where:

- an applicant files a placeholder continuation;

- many of an applicant’s applications are filed in a short time period;

- an application (or portfolio) is deemed to be long or complex;

- an applicant adds new independent claims during prosecution;

- an applicant does not abide with a request from a USPTO official that does not have a regulatory or statutory basis and is not memorialized; or

- a circumstance arises where the USPTO ends up spending more money examining an applicant’s application (or portfolio) than was paid in USPTO fees by the applicant.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

13 comments so far.

xtian

June 9, 2021 01:01 pmIBM in 2020 >9,000 issued patents https://harrityllp.com/patent300/ Even if each application spawned two patents, that means IBM filed over 4,500 patents each year on average.

If the USPTO bar is Hyatt’s filing of 400 applications, then why aren’t more articles written about IBM’s abuse of the USPTO?

We really need to crack down on IBM.

/sarc off/

(just in case)

Paul Morinville

June 7, 2021 04:27 pmGeorge, The USPTO has lost ALL moral authority when they put Hyatt’s patents into SAWS, a secret program designed to ensure that nothing gets allowed. The USPTO, as an agency of our government, has a high bar of honest and fair treatment as well as transparency owed to Americans in general and applicants specifically.

They utterly failed in that regard, and as such, ALL complaints made by the USPTO are tarnished by their own dishonest and corrupt behavior.

Therefore the accusation that Hyatt was trying to overwhelm the examiners is bunk. BS may be a better word.

George

June 7, 2021 04:14 pmThe SAWS program needs to be fully exposed and all those who got ‘trapped’ in it need to be notified. Hyatt was not treated properly by the PTO regardless of what he was trying to do (which was clearly to overwhelm Examiners in the hopes of getting easier allowance). These problems should have been brought before Administrative judges immediately, where Hyatt could have been ‘ordered’ to remedy those problems or have his applications rejected. Their decision to stall and attempt to block his applications, instead, was not the proper action to take.

George

June 7, 2021 12:34 pm@Anon

Great articles! Will read both again & keep copies of them! Don’t even disagree with anything in them. But you can’t stop science, technology & ‘progress’. It’s never been possible before and most of what comes from science and technology is ‘good’ not evil. Just think of the COVID vaccines that wouldn’t have even been possible a decade ago (because of mRNA)!

If new ‘stuff’ doesn’t work, or doesn’t work well, it won’t be used! That’s how this works. If AI doesn’t work, then it won’t be used! It’s as simple as that. But what these articles seem to be more worried about is what might happen if they ‘do’ work as claimed! Will many people become ‘obsolete’ and irrelevant? Unfortunately the answer could be yes, UNLESS they find things to do that computers can’t do well and may never do very well (like play the violin, or take care of other people).

As time goes on we’ll also have to introduce a basic minimum income for people, whether they work or not. Also the kinds of work people will do will be much more creative in nature – not rote. They will work much more on improving the environment, climate and on plant and animal conservation.

Computers won’t completely replace humans for a long time. They will mostly just become very useful ‘partners’. Whether or not society accepts that remains to be seen. As long as things get better and not worse, I think they will. As long as everyone can have food and shelter and freedom to think and speak, I think they’ll accept the change that’s coming. They definitely will in China (even without many of those freedoms).

George

June 7, 2021 12:07 pm@Anon

Since when are ’emotions’ involved in IP? Since when is facial recognition a part of IP??? Stay on track for once! Already forgot about self-driving cars? Computers that guide rockets to the Moon and back? Computers that can read X-rays more accurately than humans (with 10+ years training & experience)?! Computers that can ‘fold proteins’ which humans can’t?! Computers that can solve mathematical equations better than humans? Computers that can beat ANY human at chess, GO, and even Jeopardy? And 100 other things they can do BETTER than humans, especially search for ‘non-patent’ prior art! Want to spend 100’s of hours doing that (and bill clients $10,000’s to do it – correctly & thoroughly)?

Accept the 21st century for Pete’s sake and get with the program! I’m a lot more worried about ‘evil’ humans, than evil computers! Also much more worried about incompetent and unethical lawyers (and don’t make me start naming names).

Computers will be coming for the jobs of many lawyers and it will happen sooner than you think or like. Better to accept that sooner than later, especially since it could be a lot more lucrative too! Stocks in companies that will provide such computerized solutions and tools will see their value skyrocket! We’ll be ready and waiting for that to happen and we’ll bet big-time on AI for law, especially patent law!

So, let’s see who fares better in 20 years, OK? And let’s see how many lawyers will be left in the U.S. after that happens. My guess is less than 30% (or much more comparable to other countries). Cost will dictate what happens (as always). You think young people will want to keep paying $500/hr for ‘boilerplate’? No way! They’ll get on their ‘AI powered’ phones for legal advice and use their AI-powered patent apps (eventually for free). By the way, those ‘apps’ won’t be patented either (probably just kept trade secret). Google, IBM and maybe Microsoft will have some of the first ones (and so the USPTO will certainly listen to them and ‘adopt what they come up with’, just as they have PDF & now DOCX). If the U.S. doesn’t automate much of patent law, the Chinese will! They are not ‘stupid’ (like we are) – they are intent on beating us at everything. If we finally ‘get’ smart, we won’t let them! We need to have legal software systems – in place and used – before they do!

Anon

June 7, 2021 06:30 amAnd an older story that just popped up on my newsfeed…

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/10/yuval-noah-harari-technology-tyranny/568330/?utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR3FDQnxP5GP1AX43MI5O5FABjchWxVJ_Fb7qicEZlWIKQHjxAO5Kj2q6_g

Anon

June 7, 2021 05:55 amTo the entreaty that “None of this would have even phased a computer!”…

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/04/artificial-intelligence-misreading-human-emotion/618696/?utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&fbclid=IwAR2ATaK6isTTcCcLwt2oM8gwBOWagX1mNLzw4Tzg9ddyKaGEGlmD18yJ6Sg

ipguy

June 7, 2021 05:20 amThe entire house will come crumbling down if someone is able to show that Hyatt committed inequitable conduct during prosecution of an application 30 years ago.

Pro Say

June 6, 2021 11:20 pm+1 mike and Josh.

The quick and easy answer: Issue the darn patents.

If and when Gil asserts (any of) them, let the infringers spend their own millions to try to invalidate ’em.

Between the ocean of new IPRs . . . and new court cases . . . and new appeals . . . and ocean of billable hours . . .

What’s not to like?

mike

June 6, 2021 05:53 pman applicant files a placeholder continuation;

Whoever may find this as a concern should check themselves on the purpose an inventor seeks a patent—to get a placeholder on one’s invention. If one cannot see that, then everything is lost.

many of an applicant’s applications are filed in a short time period;

And why would this be an issue? If there are many claims an inventor wishes to seek in order to protect their intellectual property, then let them file. I fail to see how this is an issue.

an application (or portfolio) is deemed to be long or complex;

Deemed long or complex? Wow. Just wow. Perhaps the USPTO should get some sharper minds who can hold and bear comprehensive thought.

an applicant adds new independent claims during prosecution;

And what is the problem here? It is the right of an inventor to claim what needs to be claimed during prosecution.

an applicant does not abide with a request from a USPTO official that does not have a regulatory or statutory basis and is not memorialized;

I was unaware that satisfying a non-regulatory and non-statutory request from a person in the executive branch could be held against a citizen. How far shall we go? What if the request is to commit murder, and one fails to abide by that request. Would a person failing to do that render himself culpable in that instance?

a circumstance arises where the USPTO ends up spending more money examining an applicant’s application (or portfolio) than was paid in USPTO fees by the applicant.

I was unaware that the USPTO was in the business of turning a profit. They have a budget. They set their fees. So the onus is on them to balance that out.

The government seems to be grasping for straws. If they spend all this time and money and still cannot figure out how to deny the patent application, the legal remedy is simple: execute the law and issue the patent. If Congress doesn’t like the consequences with they laws they pass, then they have the power to fix it.

USPTO, your job is to execute the law on the books. So if you can’t deny, then you must comply.

Josh Malone

June 6, 2021 05:15 pmWe got the message. Patents are for big corporations, not for inventors.

George

June 6, 2021 03:13 pm“The Federal Circuit concluded that Hyatt’s prosecution techniques were “unique” and “overwhelmed the PTO”.”

None of this would have even phased a computer! All these matters could have been made ‘crystal clear’ by a properly trained computer/AI system, at least to the extent that it could have made the job of examiners and judges much, much, easier (and even have automatically created visual organization, prior art, and dependency charts, to make matters easier)!

A computerized system could have thoroughly examined all 400 applications, found all relevant prior art (including ALL relevant ‘non-patent’ prior art) in less than maybe an hours time! So the problem here is just that our patent system is now completely ‘antiquated’ and still TOTALLY DEPENDENT on extremely time consuming human labor, which is no longer necessary and which only hinders progress! A computer system could have done most of the analysis required for the ‘proper’ handling of all 400 applications – FOR FREE (in an hour) – NOT $10,000,000 and DECADES! Which is better?! If there really are ‘aliens’ visiting our planet, they’d laugh their heads off at our stupidity and ‘fantastic waste of time’!

Time to join the rest of the 21st century’s ‘computer savvy’ world and save everyone 1000’s of hours of unnecessary, wasteful, SUPER-EXPENSIVE and frankly very boring ‘nonsense’. It’s all totally unproductive and completely destroys the incentive to create anything new!

Inventors want to be able to ‘make a living’ inventing (hopefully) new and (hopefully) useful things, they don’t want to spend ‘waste’ their entire ‘precious’ and potentially very valuable lives in court, fighting to be able to do that. What other ‘profession’ wants that? What other ‘profession’ WOULD TOLERATE having to do that – all the time?!

It’s up to the USPTO and Congress to ‘get their act together’ and finally start HELPING inventors, invent – not continually finding ‘new ways’ to hinder them from doing so!

Computers can now solve 95%+ of all these problems! They can also create a system that (at least) will be 100% consistent! A far cry from what we have now – which is simply an UNMITIGATED MESS, having no consistency at all and rife with both bias and subjectivity (as clearly evidenced above)! Even the courts can’t agree with each other!

Paul Morinville

June 6, 2021 02:30 pmThe USPTO has only admitted that two inventors are in the SAWS program. Gil is one. I am the other.

As long as they have Gil in a secret program intended to clock out the inventor and never issue the patent, the USPTO has no right to claim laches.

The USPTO is corrupt to the bone on any inventions that have a large effect on the market. Gil’s are those type of invention.