“Religious marks have historically failed to register if manipulated or contextually made to be disparaging, or when their use is merely descriptive. Tam and Brunetti may have upended the former limitation. If religious marks might register in a manipulated manner or generally, that registration could – if heavily policed – effectively stifle religious freedom.”

Editor’s Note: The following article is authored by the pro bono counsel for cancellation petitioner, Elevated Faith LLC.

A case that is currently before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), Proceeding No. 92071980, is no run-of-the-mill cancellation petition. Elevated Faith LLC v. GODISGHL, LLC, concerns the right to register religious symbols and exposes critical flaws in trademark examination; in some ways it might be considered a progeny of Matal v. Tam and Iancu v. Brunetti. Naturally, it also involves a celebrity.

On August 8, 2013, the musician Nick Jonas posted on Instagram the following symbols in the form of a tattoo, with the statement “God is greater than the highs and lows.”

(I’m not sure what inspired the tattoo; I’ve tried contacting Nick but he seems to have better things to do than to discuss his social media history with me.) The post received over 180,000 likes, but also led to countless copycat tattoos and opportunistic retailers. A Google image search of the phrase “God is greater than the highs and lows” shows a significant online marketplace of the symbols linked with the phrase and with the biblical chapter Romans 8. (I submitted 700 such examples in a recent brief following only a few hours of searching.)

Nearly two years later, the brothers Jeremy and Joseph Guindi applied for trademark registration of the symbols. (The Guindi brothers would eventually formalize as GODISGHL, LLC.) They described the mark as containing the literal elements G and V, and made no mention in their application of the symbolic phrasing or reference to Romans 8. (Later, their website and social media accounts would prominently feature the headline “God Is Greater Than The Highs And Lows,” followed by “Romans 8:39.”)

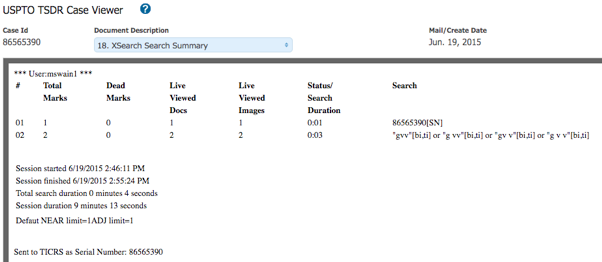

The GODISGHL application file, Serial No. 86565390, shows that the trademark examiner spent only a few minutes searching “gvv” in the database. There is no evidence that the examiner searched outside the X-Search database, and the mark was published in the Official Gazette accompanied by “Mark Literal(s): G V V.” The mark registered on April 18, 2017, in Class 25 for various forms of apparel.

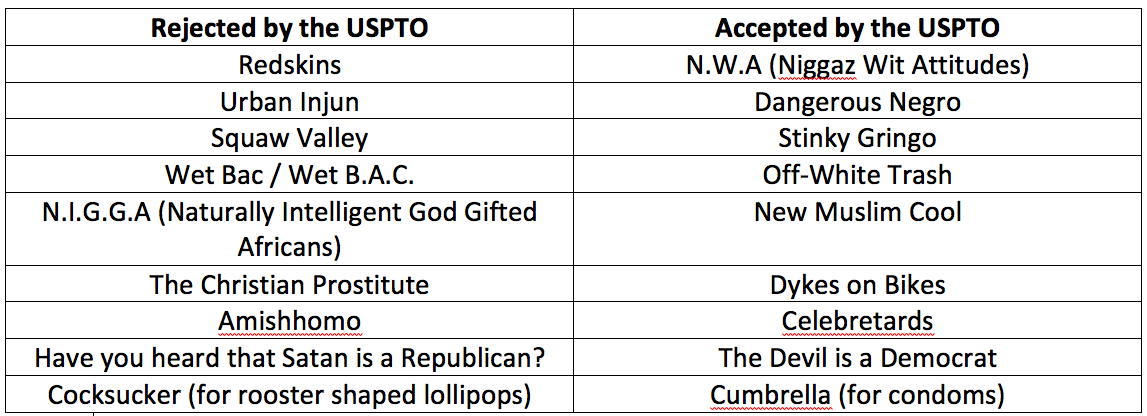

What does this have to do with Tam and Brunetti? These cases have limited the Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)’s ability to bar registration on obscene (think FUCT) and offensive (think swastikas) marks. As partial justification for its decisions in these cases, the Supreme Court was critical of the USPTO’s arbitrary decisions on what marks should be limited by Lanham Act § 2(A):

No trademark by which the goods of the applicant may be distinguished from the goods of others shall be refused registration on the principal register on account of its nature unless it…[c]onsists of or comprises…

matter which may disparage…persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, or bring them to contempt, or disrepute…

Immoral…or scandalous matter.”

Prior to the Tam decision, the USPTO applied the Act in suspect ways:

As Justice Alito wrote in Tam, “The admitted vagueness of the disparagement test and the huge volume of applications have produced a haphazard record of enforcement. (Even today, the principal register is replete with marks that many would regard as disparaging to racial and ethnic groups.)” Haphazard enforcement also extends to examination of religious marks.

On March 2, 2019, a Chinese manufacturer applied for registration of the mark “God is Greater Than The Highs and Lows.” An Office Action was issued against this Serial No. 88322995, claiming that the phrase is a “commonly used religious inspirational message,” and therefore the mark could not register under Sections 1, 2, 3, and 45 of the Lanham Act. Each exhibit that the trademark examiner used as a basis for this Office Action featured the symbols registered in the GODISGHL mark / Jonas tattoo. The symbols are inseparable from the phrase, but in one case the USPTO has determined that they are registrable and in another case that they are not.

The Problem with Registering Religious Symbols

Religious marks have historically failed to register if manipulated or contextually made to be disparaging, or when their use is merely descriptive under TMEP § 1202.17(e)(iv). Tam and Brunetti may have upended the former limitation. If religious marks might register in a manipulated manner or generally, that registration could – if heavily policed – effectively stifle religious freedom.

The G>^V symbols may be historical; they are just as likely a product of the social media era, in which an image is rapidly associated with an idea and upon a million shares becomes axiomatic. In either case, trademark registration of the symbols should be barred because the symbols and phrasing cannot serve as true source identifiers. (Even my babysitter obtained a tattoo of the symbols as biblical code for Romans 8 with no knowledge of the viral Jonas post or the registration holder.)

The Supreme Court decided that the Section 2(A) disparagement clause of the Lanham Act inappropriately impinged upon freedom of speech. In another constitutional scenario with a twist, unchecked registration of religious symbols could impinge upon the free exercise of religion. If, for instance, an e-commerce company is allowed to obtain trademark registrations on biblical phrases, or symbolic shorthands for phrases, then it could prevent other retailers from selling goods with those religious references to the exclusion and detriment of consumers who want to freely purchase such goods in furtherance of their religious practices. Worse, with registrations in hand, the effective monopoly holder of such religious references could alter their meanings through product orientation and message association.

Is it a crazy assertion that trademark registration could stifle religion? Maybe on its face. But as Professor Mara Einstein writes in Brands of Faith:

[O]ur interactions with advertising have led us to expect certain things from marketers, specifically convenience and entertainment. These expectations have migrated to the realm of spiritual practice. Religion is no longer tied to tame and place; it can be practiced any time of the day or night via the media without going to a sacred space. So traditional religious institutions have to compete not only with brick and mortar churches, but also with religion presented in other forms. Religion is increasingly moving from pew to pixel.

Or as Chris Stokel-Walker wrote in a 2017 BBC article entitled How Smartphone and Social Media are Changing Christianity:

Story Time Jesus…became a viral meme in 2012 and has remained popular since. Others include Bunny Christ and Republican Jesus. Many of these memes may have started as jokes, but they are being used to spread religious ideas, too.

People are less interested in the religion espoused by their local house of worship in favor of what’s on their social media feeds. At the same time, Christian apparel sales are booming, particularly in younger demographics where consumers evangelize their faith and values via Instagram posts. As Kerusso founder Vic Kennet has put it, “That’s what it’s all about – turning people’s attention toward God and our Savior. Plant a seed, start a conversation and let God do the rest.”

Since the initiation of this TTAB case, the G>^V registration holder has filed new applications around the symbols, seeking to monopolize multiple markets. As online sellers of merchandise featuring the G>^V symbols begin to receive nastygrams and takedown notices, and the thousands of people who have the G>^V tattoos realize that they’ve permanently inked themselves with a company’s trademark, I’m waiting to find out, What Would Jonas Do?

John Sommer, general counsel for Stussy and attorney before the Supreme Court in Iancu v. Brunetti, is counsel for GODISGHL, LLC in the TTAB case.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

#God’sNotAnonymous

August 27, 2020 05:33 pmAnd in comes in the mighty catch all “failure to function” clause! Da da da DAAA!

Let’s take a moment to remember that trademarks, in their most basic form, are meant to serve the purpose of identifying a source. I see a “swoosh,” I think Nike. I see four interwoven silver circles on a car, I think—well, I’m not a car person, but I know this is a good quality car sold by a single manufacturer even if I don’t recall who exactly sells it.

BUT when I see G>^v, which is sold by hundreds of vendors on Etsy alone, I don’t think “some company.” If anything, I think, “Hey! That’s the Jonas tattoo!”

It’s sad that a Christian retailer has sunk so low as to falsely claim ownership of a symbol that was viral way before it’s business was even formed. Even worse, it’s attempting to

prevent other Christian retailers from selling goods under its *cough* fraudulently obtained *cough* mark.

Maybe I’ll file a trademark application for 1Tim.6:10. . .

Anon

August 27, 2020 10:55 amI was very disappointed with this piece.

First, it seemed like nothing more than clickbait, as the sense of sensationalism outweighs any semblance of legal content.

But then I noticed the Editor’s note about who the author is, and my view of the piece was lowered further.

“If religious marks might register in a manipulated manner or generally, that registration could – if heavily policed – effectively stifle religious freedom.””

(my emphasis)

This statement is utter hogwash.

Religious Freedom cannot be stifled by a mark serving a notification of origin for items in commerce.

What would be ‘stifled’ would be competing commerce – and that is a far cry different than the notion of Religious Freedom.