“According to the Court, Rogers plus Twentieth Century Fox means that ‘trademarks registered for arguably artistic products and services are not worth the paper that the trademark registration is printed upon.’”

On May 8, the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado granted National Geographic’s Motion to Dismiss Stouffer’s amended complaint in Stouffer v. National Geographic Partners, LLC. Stouffer sued National Geographic for trademark infringement, unfair competition, and deceptive trade practices. In response, National Geographic asserted that Stouffer’s claims were trademark-based and must be dismissed in order to protect National Geographic’s First Amendment interests. The Court addressed the question of what protections the First Amendment provides to those accused of trademark infringement and ultimately granted National Geographic’s motion to dismiss with prejudice.

In a previous Rule 12(b)(6) motion practice (the Prior Order), the Court evaluated the Rogers test, as set forth in Rogers v. Grimaldi, and concluded that the test “did not strike the appropriate balance between trademark rights and First Amendment rights.” The Court introduced a six-factor genuine artistic motive test and gave Stouffer an opportunity to re-plead its claim. National Geographic was also given an opportunity to again move to dismiss. Thus, Stouffer filed an amended complaint and National Geographic filed a Rule 12(b)(6) Motion to Dismiss Plaintiff’s Amended Complaint.

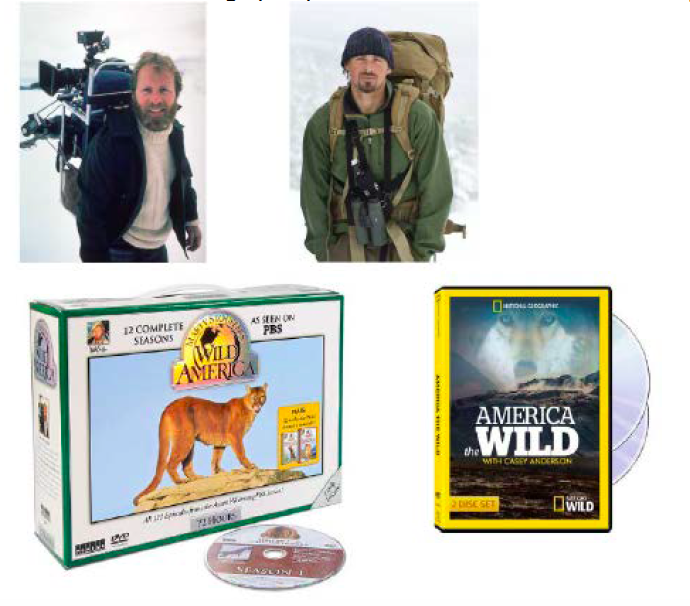

Stouffer’s “Wild America” and National Geographic’s Accused Series

From 1982-1996, a nature documentary series, Wild America, was produced by Marty Stouffer Productions and televised on the Public Broadcasting Service (“PBS”). Throughout the time the series was televised, Stouffer developed a “unique filming style for the show, which utilized slow motion, close-ups, and time lapses to give viewers a more immersive experience than other nature and wildlife documentary programming.” Further, the series was known for a unique image of two bighorn rams butting heads.

The hosts interacting with rams, supposedly “invoking the imagery from Wild America’s introductory scene, in which two rams butt heads dramatically”:

In 2001 and 2010, National Geographic launched two television stations featuring nature documentary programming. National Geographic engaged in discussions with Stouffer regarding potentially licensing or purchasing the Wild America film library. However, National Geographic declined to purchase the film library. In 2010, a National Geographic executive contacted Stouffer requesting permission to use the title “Wild Americas” or “Wildest Americas.” Stouffer declined and responded that “Wild America” was protected by trademark and the proposed titles are too close to the trademarked name. Thus, National Geographic named its series “Untamed Americas” within the United States and “Wild America” outside the United States.

Over the next several years National Geographic released additional TV series that Stouffer alleged were very closely titled to Wild America, “replicat[ed] the most minute details of Wild America” and included “many iconic images from Wild America, including, among others, the image of two big horn sheep head-butting one another.” In total, four National Geographic TV series were at issue, Untamed Americas, America the Wild, Surviving Wild America, and America’s Wild Frontier, hereinafter referred to as the “Accused Series.”

District Court Review of Rogers Test

In reviewing Stouffer’s amended complaint, the Court noted that the only issue to address was whether National Geographic’s First Amendment interests required the Court to dismiss Stouffer’s complaint. The Court explained that trademark claims are normally evaluated according to the likelihood of confusion test, but the First Amendment requires some tolerance when it comes to expressive works. The Court noted that a two part test arose from the Second Circuit decision in Rogers v. Grimaldi, which questioned: 1.) whether a title has “some artistic relevance” to the underlying work, and 2.) whether the title “explicitly misleads” as to the source or content of the work. However, the Court noted that “courts [have struggled] to assimilate unanticipated factual patterns into the Rogers test—factual patterns that raise legitimate concerns about whether Rogers tilts too far in favor of the junior user’s First Amendment interests.” In the Prior Order, the Court proposed a six-factor test to assist in answering the question, “Did the junior user have a genuine artistic motive for using the senior user’s mark or other Lanham Act-protected property right?”

Although National Geographic asserted that Rogers should be the governing test, the Court declined to revert to the Rogers test for several reasons. Initially, the Court noted that Rogers is not designed to “dismiss cases before discovery”. Further, the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Twentieth Century Fox TV v. Empire Distribution, Inc. interpreted Rogers “explicitly misleading” prong to mean “the junior user much make ‘overt claims or explicit references’ to association with the senior user.” The Court noted, “the use of a mark alone is not enough to satisfy this prong of the Rogers test.” According to the Court, Rogers plus Twentieth Century Fox means that “trademarks registered for arguably artistic products and services are not worth the paper that the trademark registration is printed upon.” The Court explained that under Rogers and Twentieth Century Fox, a junior user can market the same product or service under the same mark as the senior user as long as the junior user makes no overt claims to association with the senior user. The Court concluded that the Rogers test is “needlessly rigid and fails to account for the realities of each situation.”

Genuine Artistic Motive Test

The Court turned to the six-factor genuine artistic motive test set forth in the Prior Order. The Court evaluated each of the six factors:

- Do the senior and junior users use the mark to identify the same kind, or a similar kind, of goods or services?

- To what extent has the junior user added his or her own expressive content to the work beyond the mark itself?

- Does the timing of the junior user’s use in any way suggest a motive to capitalize on popularity of the senior user’s mark?

- In what way is the mark artistically related to the underlying work, service, or product?

- Has the junior user made any statement to the public, or engaged in any conduct known to the public, that suggests a non-artistic motive?

- Has the junior user made any statement in private, or engaged in any conduct in private, that suggests a non-artistic motive?

Following a brief analysis of each factor, the Court noted that there was some evidence, such as National Geographic’s use of “Wild America” outside of the United States, that pointed towards a subjectively unartistic motive. However, the Court also pointed out that National Geographic’s use of titles that describe the content of the Accused series weighed heavily in National Geographic’s favor. The Court further explained that National Geographic’s selected titles, which correspond closely to nature documentary programming, led to a strong “objective inference … that its motive was genuinely artistic.” Further, nothing in the amended complaint suggested that National Geographic was attempting to “ride Stouffer’s wave.” Finally, the amended complaint provided only generic accusations that the Accused Series was not National Geographic’s original expressive content. Thus, the Court concluded that the objective facts established that National Geographic’s titles for the Accused Series deserved First Amendment Protection, regardless of whether Stouffer could prove likelihood of confusion. The Court thus dismissed Stouffer’s claims with prejudice.

Images taken from court order

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Anon

May 14, 2020 08:47 amnothing in the amended complaint suggested that National Geographic was attempting to “ride Stouffer’s wave.”

This appears to the dagger.

As to the amended test, it seems to be much more ‘friendly’ to protecting an artist’s first use and ties to the purposes of TM.

Of course, TM is not my usual playground, so I am open to be persuaded otherwise.