“In essence, [since eBay], patent law remedies are no longer ‘blind’ to the characteristics of the participants, but instead those features control.”

In the inaugural installment of this regular IPWatchdog guest column, “Rader’s Ruminations,” Judge Randall Rader, former Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), will share some of the insight he has gleaned from his 35 years of experience as a law school professor, as well as his time as a CAFC judge, in hopes of shedding light on the path to a brighter future for patent law.

The most striking (and embarrassing) mistake of law in modern patent law history occurred in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, 347 U.S. 388 (2006). This mistake led to an alarmingly incorrect outcome and a monumental disruption of U.S. innovation policy.

The most striking (and embarrassing) mistake of law in modern patent law history occurred in the case of eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, 347 U.S. 388 (2006). This mistake led to an alarmingly incorrect outcome and a monumental disruption of U.S. innovation policy.

Before exploring the blatant mistake (which most patent lawyers do not grasp), consider the nature of property rights. Title 35 defines a patent as a right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing an invention. 35 U.S.C. 154 (a)(1). When someone trespasses on a property right (camps in your backyard or presumes to use your invention), the general — not automatic — remedy is to remove the trespasser. Thus, the traditional and longstanding remedy for trespass on a patent property right is a permanent injunction. By making removal of an established infringer/trespasser optional in eBay, the Supreme Court vastly undercut and devalued every patent’s exclusive right. This erroneous outcome is a cataclysmic policy error, but that policy miscarriage is not itself the embarrassing error of law.

The Embarrassment

The embarrassing error of law is the Supreme Court’s failure to do one of its most fundamental jobs — reconciling apparently conflicting provisions in the same statute. The damaging result in eBay occurred because the Supreme Court did not even attempt to reconcile 35 U.S.C. 283 (“courts . . . may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent violation of any right”) with 35 U.S.C. 154 (a) (1) (the basic right to exclude) and 35 U.S.C. 261 (“patents shall have the attributes of personal property”). Instead, the Court emphasized that Section 283 used the conditional term “may” and, with shockingly abbreviated reasoning, imported a conditional injunction that today means a right to exclude is rarely a right to exclude at all!

If the Supreme Court had undertaken to do its job, it would have discovered that Section 283 itself sets forth the reconciling principle, namely equity. The “principles of equity” recited in section 283 themselves show the reason that Title 35 necessarily had to use “may” to ensure that injunctions were a “general” rule, not an “automatic” rule. The “principles of equity” include at least the four factors specified in eBay: irreparable harm, an inadequate legal remedy (damages), a balancing of hardships, and the public interest (in health and safety). (Actually, the Court’s four-part listing is also an error because equity involves at least seven factors, but an excellent law review details this mistake. The Supreme Court’s Accidental Revolution? The Test for Permanent Injunctions, 112 Colum. L. Rev. 203 (March 2012).). The pivotal principle of equity, which would reconcile the “may” in section 283 with sections 154 and 261, is the public interest in health and safety.

The Real Reasons for ‘May’

This reconciling principle comes into focus in light of some simple factual scenarios. If an infringed patent covered a wastewater treatment plant, the district court could not automatically shut down the infringing plant without endangering public safety. Recognizing that an exclusive right could implicate public health, title 35 used the term “may” in section 283 to ensure that district courts could exercise a narrow discretion to preserve public safety.

Incidentally, this factual scenario is not a hypothetical, but the actual case of City of Milwaukee v. Activated Sludge, Inc., 69 F. 2d 577 (7th Cir., 1934). In that case, the 7th Circuit vacated a permanent injunction on infringement to ensure that the city did not dump its waste into Lake Michigan. Another example might be a heart pacemaker. The statute ensures that the district court does not have a mandatory duty to shut off a life-saving device even if it has been proven to infringe. As an aside, the same principle applies to real or personal property (as again suggested by title 35); for example, a court would not shut off a right of access to a hospital regardless of the established ownership of the egress corridor.

Thus, the principles of equity themselves reveal the reason that the statute uses the conditional “may” in section 283, namely, to protect the public interest in health and safety. If the Supreme Court had done its job and sought a reconciling principle in title 35, it would have found it within the language of section 283 itself (“in accordance with principles of equity”). As Patent Law In a Nutshell succinctly states: “The ‘may’ was necessarily present in the statute to guard against the rare instance when enforcing a patent could endanger public health and safety.” Id. Nutshell, 4th Ed. at 472.

The Lower Courts Had It Right

Tragically, the eBay record shows that the Supreme Court could have reconciled the apparent inconsistencies and preserved the right to exclude in another, perhaps even easier, way. The lower court jurisprudence had already done the reconciling work by articulating a correct rule. Under the correct rule before eBay, the courts followed a “general rule that courts will issue permanent injunctions against patent infringement absent exceptional circumstances.” See, 401 F. 3d 1323, 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2005)(emphasis supplied). The Supreme Court read this rule as “a rule that an injunction automatically follows.” eBay at 390 (emphasis supplied). If the Court had simply evaluated the axiomatic difference between a “general” and an “automatic” rule, the inquiry itself would have given proper weight to the “absent exceptional circumstances” reference. Without doubt, those “exceptional circumstances” invoke with certainty the equitable health and safety interests. Instead, the Supreme Court misconstrued and then reversed the correct general rule.

Collateral Damage

This brief article details the Supreme Court’s embarrassing legal mistakes in eBay. The policy implications of this mistake are wide-ranging and harmful to patent law and innovation policy in general. One of those policy flaws deserves more attention. With gratitude to the Greco-Macedonian roots of modern jurisprudence, legal decisions find their resolution in the law and the facts, not the irrelevant characteristics of the parties. To state it more directly, our laws promise to govern without respect to race, creed, ethnicity, gender, politics, size, corporate status, or other characteristics of the parties.

Yet, under the eBay regime, party attributes generally control the injunction decision. To win a permanent injunction, the property owner (who has already proven validity and infringement) must now show a powerful case of “irreparable harm” under the eBay factors. With an infringer offering to pay a minimal royalty (“minimal” because an injunction is not likely in play) and with hardships for both the infringer and the patent owner, the controlling eBay factor is the showing of harm. A court will invariably require a loss of market share to prove this “irreparable harm.” Thus, only a patent owner with a presence in the market can even attempt to prove entitlement to an injunction. Universities, research clinics, professors, or other non-corporate inventors need not even apply; they cannot qualify. In essence, patent law remedies are no longer “blind” to the characteristics of the participants, but instead those features control.

A Confounding Concurrence

Any doubts about the way the system works disappear with a reading of the concurrence of Justice Kennedy and three other Justices, which identifies a segment of the patent “industry” that only uses patents as “leverage.” This reference to proverbial “non-practicing entities” overlooks that the characteristic of producing goods is not an enforcing or even relevant principle of validity, infringement or other statutory patent doctrines. Moreover, it is a characteristic that excludes a vast segment of the inventor population. After all, what is a patent if it is not “leverage” to exclude?

In sum, the Supreme Court’s most embarrassing mistake in patent law cases occurs in eBay. The Court simply does not do its job. It does not even attempt to reconcile the provisions of title 35. Chief Justice Roberts (and two of his colleagues) seem to sense the inconsistencies and faults of eBay. Their concurrence invokes Holmes’ wisdom that “a page of history is worth a volume of logic.” See eBay at 392. This passing (and unfollowed) advice seems to credit the historical “general rule” that eBay categorically rejects. Rather than upholding the long history of removing the trespasser, this irrelevant concurrence only supplies a further hint at the internal inconsistency of the Court’s most striking patent law error.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: alexmillos

Image ID: 32690747

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

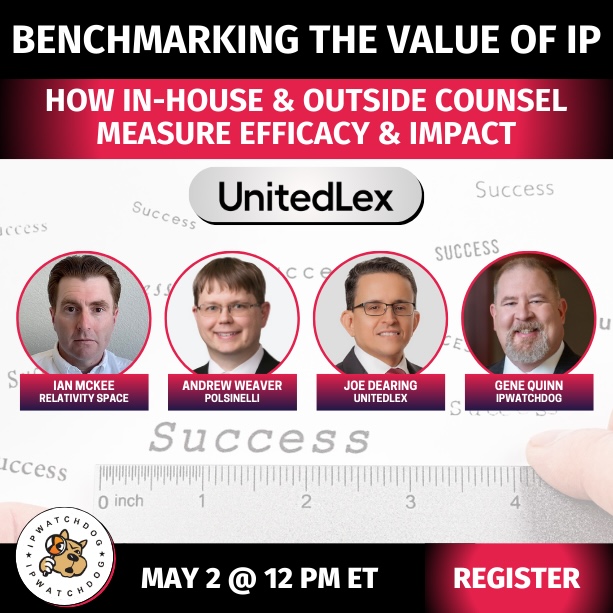

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

28 comments so far. Add my comment.

Anon

February 29, 2024 05:03 pmpatent investor – my post most likely was not up when you made your post – read through it – the reference is to a known thought experiment from psychology.

patent investor

February 29, 2024 08:58 amS,

I’m not sure Anon was guilty of making an ad hominem attack there, just of being overly descriptive. He should have just stuck with “simians” and left out the “stuck in cages being sprayed with a fire hose” descriptor. Maybe clarifying with “mental simians” or “moral simians”, but not ad hominem.

Anon

February 29, 2024 08:49 amS – no problem on the timing and thank you for circling back.

As to my point on ad hominem – you misunderstand. Ad hominem IS a proper rhetorical tool. My point instead was its use as being the ONLY rhetorical tool being used. There is a massive difference between the two (and my own use is often in cases in which the barb is on point and strikes deep TO THE MARK).

For example, the barb of “Didn’t Anon call the Federal Circuit judges simians stuck in cages being sprayed with a fire hose in this very thread?” follows from the repeated BEATINGS that the Federal Circuit judges have taken at the hands of the Supreme Court, and the wrong lessons learned from those beatings.

The simians in a cage scenario exhibits the thought experiment that conditional behavior can be employed, with the conditioning evident long after the original tie between stimulus and reaction has been instigated.

As such, it is the very opposite of MINDLESS ad hominem.

S

February 28, 2024 09:31 pmAnon,

Sorry, work has been crazy recently. I do district court work but not really the PTAB or prosecution if that’s what you mean. I have a science degree but by NO MEANS am I an inventor, hahaha.

And, I’m sorry but Anon and PatentEsq, since when did you two start having issues with ad hominem attacks? Didn’t Anon call the Federal Circuit judges simians stuck in cages being sprayed with a fire hose in this very thread? I don’t think it’s relevant how Rader was removed from the court, but come on…

PatentEsq

February 27, 2024 04:23 pmYes, if you have to resort to ad hominem attacks on the author to distract from the substance of the argument, you might have a problem.

Anon

February 27, 2024 03:01 pmBrother Anon – please do not sully the pseudonym.

Any such ‘disgrace’ has ZERO to do with views on patent law, now doesn’t it?

(hint: that’s called ad hominem – you have not shown yourself worthy enough to wield that – unlike me, of course)

Anon

February 27, 2024 01:29 pmIf disgraced former Chief Judge Rader is your hero, you might have a problem

Anon

February 27, 2024 09:15 amS,

Was I correct?

Alan

February 26, 2024 09:50 amAs always, thank you RRR for your insights. You have a unique view of the fallout of eBay from the appellate court and how this bad decision as adversely affected so many patent holders. eBay is the classical example of a bad case (bad facts) making bad case law. The problem wasn’t the outcome as to eBay and MercExchange (at least I think it would have been wrong to permanently enjoin eBay on the facts – to entirely shutdown eBay for infringing a patent asserted to cover the “But it Now” feature that I imagine today would fail 101 under Alice). However, the SCOTUS judges couldn’t help themselves and expanded non-enjoinment way beyond what it should have been with their four-factor test.

Anon

February 23, 2024 09:19 amap,

To your point of, “but that discretion is surely informed by what the applicant wants to enjoin and what right the applicant is trying to enforce.” the ‘being informed by’ MUST include the following (all of which I have noted many times in the blogosphere):

1) The nature of strict construction when one branch of the government shares its Constitutionally allocated authority with another branch.

This is traditionally a Strict Scrutiny analysis, and to my understanding has NEVER been properly addressed by the Supreme Court.

2) From 1), it follows that the words of the statute must be read in their entirety and no shortcuts are permitted.

Let’s look at all of those words in their entirety – its but a single sentence (with my emphasis added):

35 U.S.C. 283 Injunction.

The several courts having jurisdiction of cases under this title may grant injunctions in accordance with the principles of equity to prevent the violation of any right secured by patent, on such terms as the court deems reasonable.

Even the power TO use is constrained for a single purpose. ANY OTHER USE beyond that purpose is ultra vires.

3) The nature of BOTH “principles of equity” (see 3B), AND “rights secured by patents” (see 3A) must be understood in context.

3A) Critically, patents, and more precisely, the rights secured by patents MSUT BE UNDERSTOOD to NOT be a “must make” actual physical goods thing. Thus, there need not be AT ALL any actual manufacture of anything for the transgression of rights to have occurred.

3B) With the understanding of 3A, the principles of equity MUST take this into context, and the ‘default’ principles of equity, such as for example that “Injunction is the atom bomb of remedies” cannot apply.

The very first principle of equity – bar none – is that a remedy that makes the transgressed as whole as possible IS the best remedy.

Certainly, often “money” is an EASY remedy.

That though is decidedly NOT the best remedy.

What is the best remedy in the patent context? What makes whole the transgressed closest to the ACTUAL RIGHT of excluding others?

That should be extremely easy to see.

The extreme ease though has made the judiciary LAZY and that has been a problem.

Let me be very clear: ALL FOUR FACTORS must be analyzed, and No such thing as “automatic” should apply.

This though is just not the same that in ALMOST EVERY SINGLE CASE the principles of equity FOR the given purpose of the sharing of authority from the Legislative Branch to the Judicial Branch will be that best remedy of injunction.

Anon

February 23, 2024 09:02 amS,

Thank you – by the way that you phrased that, I am going to presume that you do NOT have a USPTO registration number (or, if you do, you have never had meaningful experience either in engineering in the field, or in working to obtain patent protection.

Would this be correct?

anonymous practitioner

February 22, 2024 11:02 pmI look forward to more Rader ruminations. I’ve enjoyed his writing ever since law school. I have a few quibbles with Judge Rader’s criticisms but mostly agree eBay was wrong. The decision itself is very short, and available here. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4819344338954570996

The error, I think, is eBay giving short shrift to the point that patents are property rights to exclude others. As Judge Rader says, the ordinary, “general” remedy for an ongoing trespass is to evict the trespasser. That’s not a “major departure from the long tradition of equity practice” (as the Supreme Court suggests); it’s a correct observation about how certain types of cases play out in practice. It’s true that an injunction is a discretionary remedy, but that discretion is surely informed by what the applicant wants to enjoin and what right the applicant is trying to enforce. The respondent’s brief in eBay (2006 WL 622506 for those with Westlaw access) is excellent on this point, and to this day I can’t understand why the Supreme Court didn’t affirm, dismiss as improvidently granted, or adopt the Roberts concurrence as the majority.

My quibbles with Judge Rader’s analysis:

1. The public interest in health and safety is A good reason to deny an injunction. That doesn’t mean it’s the ONLY reason or “the real reason”. The post seems to leap from one to the other, which I’m not sure is right.

2. The word “automatic” appears only once in eBay. The full sentence is: “And as in our decision today, this Court has consistently rejected invitations to replace traditional equitable considerations with a rule that an injunction automatically follows a determination that a copyright has been infringed.” Elsewhere in the opinion, when describing what the Federal Circuit actually did—several times—the opinion refers to a “general rule” and quotes the Federal Circuit’s reference to “rare instances… to protect the public interest” as a reason not to grant an injunction. I’m not sure that it’s fair to say that the Supreme Court read the Federal Circuit as applying an “automatic rule” rather than a “general” one.

Even so–Judge Rader might respond that even if the Supreme Court mouthed the words, its description of the Federal Circuit as “depart[ing] from the long tradition of equity practice” shows that the Court bought some misleading arguments.

3. eBay DID try to “reconcile” section 283 with 154(a)(1) and 261. The reasoning is terse, but it’s there at page 392:

-begin quote–

To be sure, the Patent Act also declares that “patents shall have the attributes of personal property,” § 261, including “the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention,” § 154(a)(1). According to the Court of Appeals, this statutory right to exclude alone justifies its general rule in favor of permanent injunctive relief. 401 F. 3d, at 1338. But the creation of a right is distinct from the provision of remedies for violations of that right. Indeed, the Patent Act itself indicates that patents shall have the attributes of personal property “[s]ubject to the provisions of this title,” 35 U. S. C. § 261, including, presumably, the provision that injunctive relief “may” issue only “in accordance with the principles of equity,” § 283.

-end quote-

Nonetheless, I agree with Judge Rader’s bottom line that eBay was wrong. It’s possible that my quibbles are just semantic.

I appreciate this post and look forward to reading future installments.

S

February 22, 2024 06:07 pmAnon,

I am a practicing attorney in patent law. Although I’ll decline to be more specific so as not to “out” myself.

Max Drei, apologies I’ll conceed some hyperbole in my comment. It’s definitely difficult but it also definitely happens.

Max Drei

February 22, 2024 04:42 pmS tells us that the post-Ebay reality of patent litigation in the USA today is that injunctive relief from infringing acts is “almost never” granted?

I had no idea. Is that really so?

Anon

February 22, 2024 04:35 pmS,

If I may ask (with no intention of ‘outing’ you), what is your profession and relation to patent law?

S

February 22, 2024 03:47 pmThis article misses the mark just slightly for me. I concur with the piece’s reference to the cited law review article. The Supreme Court simply did not include all of the equity factors when issuing this earthshattering opinion. And I think that is the root of the current issue in courts of almost never granting injunctions.

But I am less convinced by the universal sanctity of exclusions proposed by the Author and many commenters. There should be room to consider the equity interests of the patent holder, infringer, and the public, even beyond life-saving patents. What good does it do us to pretend that an NPE is not made whole by a royalties penalty? That equity demands that a product be pulled from the market for the benefit of another which does not exist?

Simply put, there is room in the middle between an automatic injunction (which is what it was, we were all there) and the post-eBay precedent of almost never issuing an injunction.

PatentEsq

February 22, 2024 01:42 pmMax Drei,

First of all, Judge Rader’s comments were on the legal mistake by the Supreme Court. Your comment does not contradict that.

Also, you assume that there is a public interest in keeping to a minimum the degree of restraint of trade that the patent system generates. But this is not true. The patent system creates a reward for inventors, which spurs further innovation and disclosure of inventions by those inventors and others. Without that reward, there is little motivation to innovate and disclose inventions, especially if the innovation is costly and difficult. If you keep the restraint on trade to a minimum, you also keep the reward to a minimum, and you keep the motivation to innovate and disclose inventions to a minimum. Indeed, the way to minimize the restraint on trade would be to get rid of patents, but by so doing you would get rid of a lot of motivation to innovate. In truth, you need to find the right balance. Congress struck a balance in the patent statute back in the 1950’s, and the Supreme Court should have properly construed the statute that Congress wrote, rather than just assuming that restraints on trade should be minimized.

Anon

February 22, 2024 01:37 pmMaxDrei – the public interest is fully vetted with the Quid Pro Quo in granting the patent.

I do wish that you would retain some understanding of the US Sovereign choices on patent law, given how much time you spend on US Patent Law blogs.

PeteMoss

February 22, 2024 01:15 pmA problem with many of the FC judges & the Supremes is that they never had to meet a monthly manufacturing payroll. Many are just political creatures. Rodney Dangerfield’s Back to School economic class scene should be required viewing by all IP judges. There is theory, and then there is reality.

Max Drei

February 22, 2024 12:36 pmDo I see this right? An injunction is general as opposed to automatic relief from the harm that the patent owner is suffering from ongoing infringing acts. Considerations of equity can frustrate the patent owner’s demand for injunctive relief (notwithstanding that the USPTO granted the applicant for patent a statutory right to exclude).

Considerations of equity include taking into acount what we call “the public interest”. Patents are inherently restraints of trade, so why have a patent system at all? The public has an interest in setting up a patent system but there is also a public interest in keeping to a minimum the degree of restraint of trade that the patent system generates

Why then was it so wrong of the eBay court to take “the public interest” into account when considering whether to grant injunctive relief? It’s a matter of judgement in each case, isn’t it?

PatentEsq

February 22, 2024 11:59 amAs usual, well said Judge Rader. Not only is it the most striking and embarrassing legal mistake, it is also arguably the most harmful legal mistake in modern patent law. And that is saying something.

BWL

February 22, 2024 11:48 amCogent analysis and clear articulation make for an article worth reading and remembering. Looking forward to the next Rumination. Thank you Gene, Alex, and Judge Rader!

patent investor

February 22, 2024 11:08 amI wonder when he gets to the mistake of “chasing me out the door so the power-hungry Prost followed by the power-hungry Moore could take my place”. (I know he wouldn’t have stayed Chief judge that long, but still).

SpudEsq

February 22, 2024 10:46 amSee also –

“To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;”

What is an “exclusive Right,” if not the right to exclude?

Anon

February 22, 2024 09:14 amconcerned – your point about “SCOTUS will still just rewrite the new law.” is handled by my suggestion of Congress employing their Constitutional power of jurisdiction stripping from the Supreme Court matters of non-original jurisdiction.

Of course, I also suggest that Congress clean out the fire-hosed Simian cage of the current CAFC and restock an Article III Court (to maintain the holding of Marbury with NEW (and capable) judges – would like to add that in the mold of Judge Newman and Judge Rich.

Lost In Norway

February 22, 2024 05:34 amThank you for the analysis of the case. I knew Ebay was bad, but at the time I didn’t fully appreciate it. Thank you for clearing this up for me.

concerned

February 22, 2024 04:12 amI personally was told who writes the laws in this land. The courts WROTE I met the law as written by Congress; however, I did not meet THEIR case law.

And what am I going to do about it? What is Congress going to do about it? Absolutely nothing to both questions. Even if Congress does something, SCOTUS will still just rewrite the new law. Rinse and repeat again and again.

Sad thing, everyone knows it. Recent proposed legislation even has a shout out to SCOTUS to keep their hands off. Embarrassing to even have to write such a prohibition but it will not stop SCOTUS.

Pro Say

February 21, 2024 02:10 pmJudge Rader gets it right yet again.

For their unconstitutional eBay decision, SCOTUS took off their robes, snuck out of their chambers, quietly tip-toed by Congress, and set up offices in the Capitol building.

Doing the same thing with their also unconstitutional Alice and Mayo decision.

(Keep those Rader Ruminations coming.)

Add Comment