“One could argue that a set reproduction limit would encourage artists to share their material and assist in the development of non-copyright infringing AI image generators.”

From SAG-AFTRA strikes to the class action lawsuit of McKernan against Stability AI, Stability Diffusion and Midjourney, the creative industries are concerned with the ability of AI systems to produce outputs in the likeness of their original works.

From SAG-AFTRA strikes to the class action lawsuit of McKernan against Stability AI, Stability Diffusion and Midjourney, the creative industries are concerned with the ability of AI systems to produce outputs in the likeness of their original works.

Earlier this year, a class action lawsuit against popular generative AI developers Stability AI, Midjourney, and DeviantArt was filed in the United States alleging copyright infringement. McKernan and others claimed that generative AI outputs have reproduced a significant portion of their original work.

Judge Orrick in the Northern District of California has dismissed a class of claimants that do not have copyright registrations on their work – a prerequisite for cases within the United States. Albeit an American case which has now been struck, the claim of copyright infringement against AI systems would have merit within the UK. It pushes us to consider the injunction request filed by Getty Images in a London court against Stability AI on the grounds that outputs resemble the collection of images originally owned by Getty.

Let us ask the big question: Are generative AI developers infringing upon the copyright of visual artists through their outputs? Do we need ad hoc regulations that have the capacity to prevent infringement alongside new laws that are triggered after infringement has taken place? Would users be liable for copyright infringement of AI systems?

Big Questions, Short Answers

We know that AI developers do in fact train their systems using original human-generated work. A study by Somepalli et al has found that approximately 1.88% of random generations based on a sample of the famous ‘LAION (Large-scale Artificial Intelligence Open Network) Aesthetics’ on a Stable Diffusion model were highly similar to the original training material. This leads us to conclude that, in theory, it is possible for outputs to be highly similar to the original training data used to develop generative AI systems.

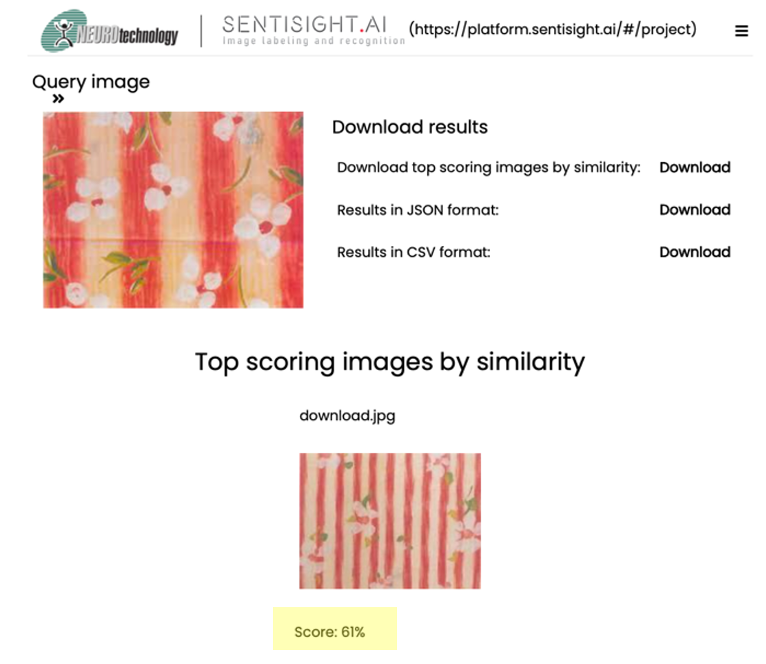

AI and its use of data mining has increased the scope and scale of generating outputs at the drop of a hat. It is accessible to millions of users all over the world. If we do not specify exactly how much copying would count as infringement within the phrase “substantial similarity,” we could see an increase in claims following the unclear scope of the standard. After all, developers do need to use original images to train their systems. Unlike human copying, we could stipulate the extent of copying with machines. You could also monitor the similarity of outcomes to the original images used to train these systems using AI copy detection models.

As a test, I ran the wallpaper patterns compared in the famous Designer Guild case to identify the degree of reproduction. Much like facial recognition systems, the platform was able to identify a numerical degree of similarity. This sample gives us a glimpse into the advantages of relying on AI to solve AI based problems.

Examining One Solution

With large-scale copy detection models now accessible to developers, one could argue that a set reproduction limit would encourage artists to share their material and assist in the development of non-copyright infringing AI image generators. This would also provide developers with the confidence and legal certainty to engage in development activities.

The cases filed by Getty and the class action lawsuit filed by McKernan have pushed governments to realize that smaller victims of infringement in an age of AI do not have the financial resources to file and contest claims of copyright infringement. A much more effective solution would be a clarification of what is allowed to reduce the incidents of infringement.

When considering the impact of infringement on users of such systems (you and me) it is worth noting that users would qualify as owners of rights in computer-generated images (s9(3) of the CDPA 1988). This would mean that if AI outputs reproduce a significant portion of original work used as training data, users would be unassuming perpetrators of copyright infringement. Since copyright infringement does not look at intent, users would automatically qualify as primary infringers.

How could we prevent this? A reproduction limitation for generative image developers (a percentage?) could be the solution. A quantitative reproduction limit is not unheard of and is a policy adopted by Germany within their copyright regime . This exception was created for scientific research in line with with the specific intention of creating an innovation-friendly system which is easier for developers to understand and apply.

I would argue that the main difficulty in introducing a policy would be ensuring that it does not discriminate between AI and human outputs. For now, we must wait and watch AI copyright cases trickle through court systems before jumping the gun.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Author: Iurii

Image ID: 8775301

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Anon

December 19, 2023 03:31 pm..for example, the stated assumption of users of AI AS BEING INFRINGERS does not stand (as of yet), here in the US, and the notion of “preventative measures” is not one our side of the pond would likely embrace (at all).

Anon

December 19, 2023 03:29 pmI have to wonder just how applicable any of the underlying reasoning (from a UK Sovereign vantage point) is actually amenable to a discussion under the Rule of Law for the US Sovereign.

Not only are our intellectual property laws different, but we have different Constitutional drivers (chief among them our First Amendment).

Without more, I am afraid that this article provides me no takeaway for my legal practice here in the States.