“Over the decades of intense promotional activity, [Plaintiff] has advertised its products using many different themes, but never did it advertise that consumers should look for any of the things it now claims constitute protectable trade dress as source-identifiers.” – E.D. of VA in TBL Licensing

Brand owners frequently encounter significant challenges in obtaining federal trade dress registration. The recent ruling in the Eastern District of Virginia confirmed that TBL Licensing, LLC, the brand owner of Timberland boots, was not an exception to this struggle.

Brand owners frequently encounter significant challenges in obtaining federal trade dress registration. The recent ruling in the Eastern District of Virginia confirmed that TBL Licensing, LLC, the brand owner of Timberland boots, was not an exception to this struggle.

Unlike a word mark, a product design can never be inherently distinctive as a matter of law because consumers are aware that such designs are intended to render the goods more useful or appealing rather than identifying their source. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 212-213 (2000). In order to obtain a federal trademark registration for a product design, the applicant must establish secondary meaning. In addition to the regular requirements to show secondary meaning involving word marks (i.e., evidence of long-term use, advertising and sales expenditures, examples of advertising, affidavits and declarations of consumers and customer surveys), “Look for” advertising is an important step to establishing the secondary meaning required for a federal trade dress registration. As far as product design cases are concerned, “Look for” advertising can be the most effective evidence provided by an applicant, as other forms of evidence may carry less weight.

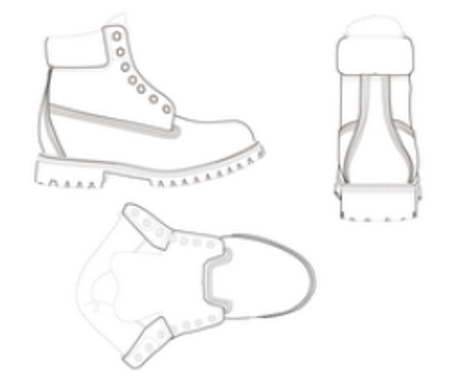

For example, in TBL Licensing, LLC v. Vidal, No 1:21-cv-00681, 2022 WL 17573906 (E.D. Va. Dec. 8, 2022), TBL Licensing, LLC (“Timberland”) argued that its sales and advertising of boots with the claimed features were so substantial that trademark rights must be attached.

The court acknowledged that the figures were “impressive,” but similar numbers that would have established secondary meaning in a word mark failed to do so for a product design. In assessing sales numbers in product design cases, a product’s market success more accurately reflects the desirability of the product configuration rather than the source-designating capacity of its features. The court observed that Timberland’s efforts to utilize large advertising expenditures as evidence of secondary meaning encountered the same issue since the significant expenses did not prove that the advertising effectively created secondary meaning concerning the product. Ultimately, despite large sums and over 50 years of advertising, Timberland had not produced any evidence that it had engaged in “look for” advertising. Without “look for” advertising, Timberland failed to link its large sales and advertising numbers with “the one thing it needs to prove: that amidst a sea of similar-looking boots, consumers nevertheless can identify Timberland’s product just by the eight specified product features irrespective of any other marks used on or with the product.” The court explained:

“The advertising evidence that [Plaintiff] offers in this case is notable for the lack of ‘look for’ advertising. Over the decades of intense promotional activity, [Plaintiff] has advertised its products using many different themes, but never did it advertise that consumers should look for any of the things it now claims constitute protectable trade dress as source-identifiers, such as eyelets, lug soles, the collar, and so on, let alone all the elements together.”

Ineffective Look-For Advertising

According to the court in TBL, customers will not typically see a design as indicating a unique source of goods. Instead, an applicant must teach customers to “look for” whatever design feature is intended to be a source identifier. And the applicant must do so in a way that doesn’t emphasize function over source-identification. The court noted that whenever Timberland’s advertisements did mention the applied-for features, the advertisements discussed the functional benefits of those features, such as waterproofing and durability. Because functional designs cannot function as trademarks, this sort of advertising fails to establish distinctiveness as a matter of law. “Look for” advertisements also fail if the advertisements cause consumers to look for traditional trademarks, such as words or logos.

In TBL, the submitted advertisements showed various advertisements and in-store displays featuring large-scale depictions of the registered TIMBERLAND word mark and Timberland’s registered tree logo to identify the products as Timberland’s. Customers would see the traditional marks “long before” they get close enough to determine whether the product contains the claimed product design.

Effective Look-For Advertising

“Look for the unique earpiece design” in an advertisement depicting a headpiece with the applied-for design was considered to be effective “look for” advertising in In re HM Electronics, Inc., 2015 WL 12722655 (TTAB Nov. 17, 2005). Along with evidence of extensive sales and advertising expenditures, the applicant engaged in “look for” advertising in print advertising, bill stuffers, electronically delivered advertising and a page on the applicant’s website that directed consumers to “Look for the unique earpiece design.”

In addition to its “look for” advertising, the applicant submitted photographs of products from other manufacturers that were different than the claimed design. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) noted that the “look for” advertising was particularly effective where the applicant also established that it is common for manufacturers in the industry to design headsets with unique looks.

In addition to its “look for” advertising, the applicant submitted photographs of products from other manufacturers that were different than the claimed design. The Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) noted that the “look for” advertising was particularly effective where the applicant also established that it is common for manufacturers in the industry to design headsets with unique looks.

Brand owners can enhance the effectiveness of their “look for” advertising by incorporating fun and catchy elements that capture the public’s attention towards their applied-for design. Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp. used clever taglines such as “Put your house in the pink” and “Think pink” to refer to their use of the color pink, and even the “Pink Panther” cartoon character as a not-so-subtle way to promote their arbitrary use of pink for fiberglass insulation. In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116, 227 USPQ 417, 423-24 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

Develop a Plan

Applicants can consider incorporating “look for” advertising in their social media, websites, or even traditional media, such as print. These advertisements should focus on drawing the public’s attention to the product design that the applicant is seeking to protect, rather than any functional aspects or other source identifying indicia, such as word marks. If applicable, “look for” advertising can be particularly effective where the industry traditionally creates unique designs. “Look for” advertising is a potent tool and often the only practical way to establish secondary meaning if applicants can commence this marketing strategy right away.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Addy

April 27, 2023 10:02 amGood practical guidance – thank you