“While there is, of course, always the risk that specifying the definition of a claim in the specification may result in the court adopting a narrower construction than may have been the case if the term was not defined, it is the authors’ view that current trends in multiple areas of patent law favor detailed definitions of claim terms.”

While it is impossible to cover all of the various issues related to claim drafting for biotech, chemical and pharma patent applications, we will highlight some of the most common issues that may come up. Some of these issues were discussed during Debora Plehn-Dujowich’s presentation at the 2022 IP Watchdog Life Sciences Masters conference, which can be viewed here.

While it is impossible to cover all of the various issues related to claim drafting for biotech, chemical and pharma patent applications, we will highlight some of the most common issues that may come up. Some of these issues were discussed during Debora Plehn-Dujowich’s presentation at the 2022 IP Watchdog Life Sciences Masters conference, which can be viewed here.

Claim Construction

The standard for claim construction during U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) examination of a patent application is the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) of the claim. See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005). This is not the standard in the Federal Courts, nor for cases before the International Trade Commission (ITC). Moreover, since November 13, 2018, BRI is no longer the standard for post-grant proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeals Board (PTAB) (i.e., inter partes review (IPR), post-grant review (PGR) or covered business method (CBM) proceedings). See Federal Register, Vol. 83, No. 197, Thursday, October 11, 2018, “Changes to the Claim Construction Standard for Interpreting Claims in Trial Proceedings Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board.” Instead, each of these latter proceedings relies on the ordinary and customary meaning of the claim term, informally referred to as the “Phillips” standard. Both of these standards are viewed in the context of the person of skill in the art (POSITA) at the time of filing. In 2016, the Supreme Court addressed the question of whether the broadest reasonable interpretation standard should apply to IPR proceedings. Cuozzo Speed Technologies. LLC v. Lee, No. 15-446, 119 U.S.P.Q.2d 1065 (Jun. 20, 2016). While the Supreme Court ruled that the USPTO’s now prior application of BRI to IPR proceedings was reasonable and within the Patent Office’s rule making authority, ultimately, the USPTO decided to replace the BRI standard for all post-grant proceedings with the federal court claim construction standard in response to comments from stakeholders and as part of the office’s “continuing efforts to improve AIA proceedings”.

From a strategic point of view, with respect to drafting claims, the differing claim construction strategies between the USPTO examination process and post-grant and court proceedings probably will not change one’s claim drafting strategies because both standards rely on the person of skill in the art at the time of filing, and both standards consider the claims in view of the specification and also allow the patent practitioner to be his or her own lexicographer. With respect to the BRI standard during examination, the MPEP explicitly constrains the standard to be consistent with ordinary and customary meaning and the specification. See MPEP 2111.

Also strategically speaking, a significant practice point is to provide a significantly detailed definition in the specification for claim terms. While thereis, of course, always the risk that specifying the definition of a claim in the specification may result in the court adopting a narrower construction than may have been the case if the term was not defined, it is the authors’ view that current trends in multiple areas of patent law favor detailed definitions of claim terms, as further detailed below. When drafting claims, one should consider whether definitions provided in the specification differ from the plain and ordinary meaning of the term, and whether a fallback position for such plain and ordinary meaning should be provided.

Markush Groups

A Markush-type claim recites alternatives in a format such as “selected from the group consisting of A, B and C.” See Ex parte Markush, 1925 C.D. 126 (Comm’r Pat. 1925). Markush groups are covered in MPEP 803.02. The members of the Markush group ordinarily must belong to a recognized physical or chemical class or to an art-recognized class.

The Examiner must examine all the members of a Markush group in the claim on the merits if the members of the Markush group are sufficiently few in number or so closely related that a search and examination of the entire claim can be made without serious burden. This is the case even if they are directed to independent and distinct inventions. The Examiner should then not require provisional election of a single species. See MPEP 803.02.

In Multilayer Stretch Cling Film Holdings, Inc. v. Berry Plastics Corp., Nos. 2015-1420, 1477 (831 F.3d 1350, Fed. Cir. Aug. 4, 2016), the Federal Circuit looked at the issue of how to interpret Markush Groups. Multilayer Stretch Cling Film Holdings, Inc. (“Multilayer”) brought suit against Berry Plastics Corp. (“Berry”), alleging infringement of at least claim 1 of U.S. Patent No. 6,265,055 (“’055”). The ‘055 patent relates to multilayered plastic cling wrap films. The District Court granted Berry’s motion for summary judgment of non-infringement based on its claim construction.

Claims 1 of the ‘055 patent is reproduced below (claim 28 had similar Markush Groups):

-

- A multi-layer, thermoplastic stretch wrap film containing seven separately identifiable polymeric layers, comprising:

(a) two identifiable outer layers, at least one of which having a cling performance of at least 100 grams/inch, said outer layer being selected from the group consisting of linear low density polyethylene, very low density polyethylene, and ultra low density polyethylene resins, said resins being homopolymers, copolymers, or terpolymers, of ethylene and alpha-olefins; and

(b) five identifiable inner layers, with each layer being selected from the group consisting of linear low density polyethylene, very low density polyethylene, ultra low density polyethylene, and metallocene-catalyzed linear low density polyethylene resins; said resins are homopolymers, copolymers, or terpolymers, of ethylene and C3 to C20 alpha-olefins;

wherein each of said two outer layers and each of said five inner layers have different compositional properties when compared to a neighboring layer. (emphasis added)

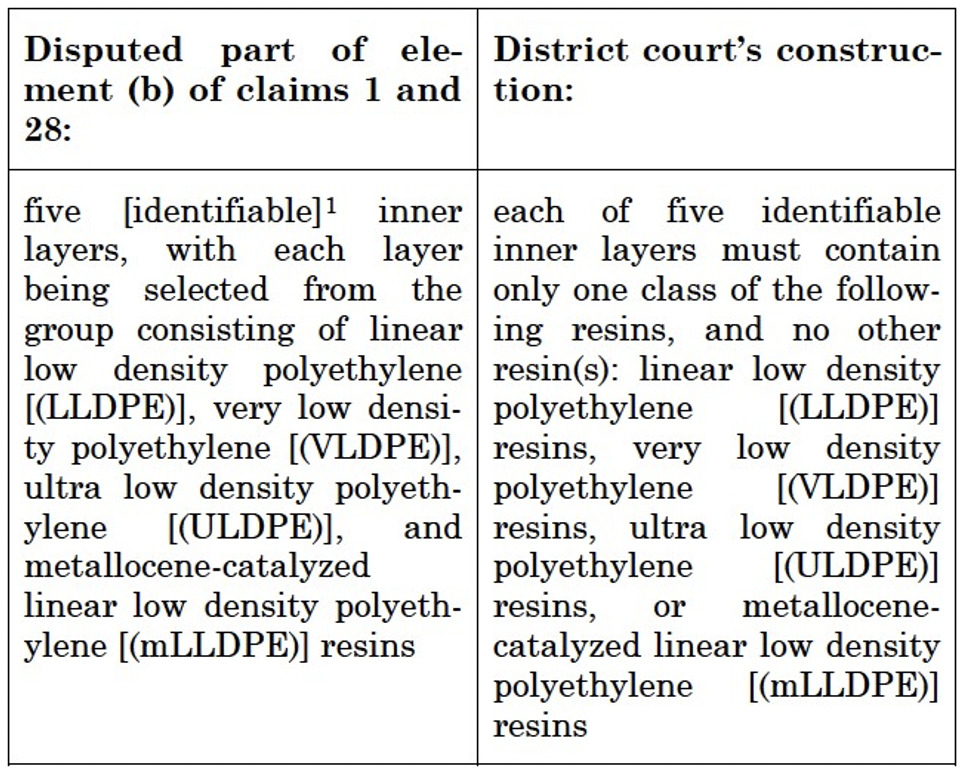

The District Court’s Claim Construction is illustrated in the chart below:

The parties had agreed that “at least one of the inner layers of the Accused Films contains blends of resins from the classes of mLLDPE, ULDPE, and LLDPE—all classes of resins separately specified in claims 1 and 28.” The Markush group in Claim 1(b) was construed by the District Court to be closed. Only one of the resins listed in Claim 1(b) could be used to construct each of the five inner layers. Blends of the listed resins were also excluded. Dependent claim 10 was held invalid under 35 U.S.C. §112(d) because it recited “low density polyethylene homopolymers” which was not recited in the Markush group of claim 1, from which it depends.

The Federal Circuit opinion was written by Judge Dyk. He described Markush groups as follows:

“[a] Markush group lists specified alternatives in a patent claim, typically in the form: a member selected from the group consisting of A, B, and C,” where “[i]t is generally understood that . . . the members of the Markush group . . . are alternatively usable for the purposes of the invention”

The following two claim construction issues were identified:

- Whether the Markush group of element (b) is closed to resins other than the listed four; and

- Whether the Markush group is closed to blends of the four listed resins.

The Federal Circuit held that the Markush group of element (b) was closed to resins other than the listed four. However, the court held that the Markush group was not closed to blends of the four listed resins. The Federal Circuit held that the district court’s grant of summary judgment of non-infringement was predicated on its incorrect construction of claims 1 and 28 as closed to blends of LLDPE, VLDPE, ULDPE, and mLLDPE. The court therefore vacated the grant of summary judgment and remanded for reconsideration of infringement under the correct construction.

Judge Dyk distinguished the case at hand with Abbot Labs v. Baxter Pharm. Prods., Inc., (334 F.3d 1274, Fed. Cir. 2003). The court in Abbott held that if a Markush claim recites “a member selected from the group consisting of A, B, and C,” the claim is presumed to permit the member to be one and only one of A, B, or C, and to exclude mixtures or combinations of A, B, and C.

The Federal Circuit in Multilayer v. Berry looked at the specification of the ‘055 patent for guidance in construing the claims. Judge Dyk noted that the specification repeatedly and consistently referenced blends in describing any and all resins, including the four resins in element (b). He also noted that the specification discussed blending the resins in order to achieve a desired range of physical or mechanical properties. Thus, he concluded that blends were included in the Markush group.

In Shire Development, LLC v. Watson Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (848 F.3d 981, Fed. Cir. 2017), the Federal Circuit also looked at the issue of how to interpret Markush Groups. Shire sued Watson for infringing claims 1 and 3 of Shire’s U.S. Patent No. 6,773,720 (the ‘720 patent).

The District Court found that Watson did infringe. However, the Federal Circuit reversed and found that Watson did not infringe because of its interpretation of a Markush group in the claims.

Claim 1 reads in part:

-

- Controlled-release oral pharmaceutical compositions containing as an active ingredient 5-amino-salicylic acid, comprising:

an inner lipophilic matrix consisting of substances selected from the group consisting of unsaturated and/or hydrogenated fatty acid, salts, esters or amides thereof, fatty acid mono-, di- or triglycerids, waxes, ceramides, and cholesterol derivatives with melting points below 90° C., and wherein the active ingredient is dispersed both in said [sic] the lipophilic matrix and in the hydrophilic matrix;

an outer hydrophilic matrix wherein the lipophilic matrix is dispersed, and said outer hydrophilic matrix consists of compounds selected from the group consisting of polymers or copolymers of acrylic or methacrylic acid, alkylvinyl polymers, hydroxyalkyl celluloses, carboxyalkyl celluloses, polysaccharides, dextrins, pectins, starches and derivatives, alginic acid, and natural or synthetic gums;

optionally other excipients…

Watson’s ANDA formulation contained two matrices, an inner lipophilic matrix, and an “extragranular space” that the D.C. recognized as the outer hydrophilic matrix. This outer matrix contained magnesium stearate as a lubricant. However, magnesium stearate is not a member of the Markush group of claim 1 (b) and is lipophilic rather than hydrophilic. The court therefore held that there was no infringement.

Thus, even though the claim preamble recited “comprising…” the Markush groups in the subsequent claim clauses, each reciting “selected from the group consisting of” were construed as being closed. The Federal Circuit held that use of the term “consisting of” creates a very strong presumption that the claim element is closed and therefore excludes any elements or steps not specified in the claim. Overcoming this presumption requires the specification and prosecution history to unmistakeably manifest an alternative meaning such as when the patentee acts as its own lexicographer.

In Amgen, Inc. v. Amneal Pharmaceuticals, LLC. Nos. 2018-2414, 2019-1086 (2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 245, Fed. Cir. Jan. 7, 2020), the issue of how to interpret Markush Groups was again reviewed by the Federal Circuit, only this time with a different result.

Amgen sued Amneal for infringing claims 1, 2-4, 6, 8-12, and 14-18 of Amgen’s U.S. Patent No. 9,375,405 (the ‘405 patent). The District Court found that Amneal did not infringe. The Federal Circuit reversed and remanded because it found that the District Court interpreted Amneal’s claims incorrectly.

The claim at issue recited:

A pharmaceutical composition comprising:

(a) from about 10% to about 40% by weight of cinacalcet HCl in an amount of from about 20 mg to about 100 mg;

(b) from about 45% to about 85% by weight of a diluent selected from the group consisting of microcrystalline cellulose, starch, dicalcium phosphate, lactose, sorbitol, mannitol, sucrose, methyl dextrins, and mixtures thereof,

(c) from about 1% to about 5% by weight of at least one binder selected from the group consisting of povidone, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, sodium carboxymethylcellulose, and mixtures thereof; and

(d) from about 1% to 10% by weight of at least one disintegrant selected from the group consisting of crospovid[o]ne, sodium starch glycolate, croscarmellose sodium, and mixtures thereof,

wherein the percentage by weight is relative to the total weight of the composition, and wherein the composition is for the treatment of at least one of hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphonia, hypercalcemia, and elevated calcium phosphorus product. (emphasis added)

Amneal’s ANDA states that its product uses “Opadry” as a binder. It was undisputed that Opadry is a composite product comprised of HPMC, polyethylene glycol (“PEG”) 400, and PEG 8000. HPMC is listed in the binder Markush group of claim 1. The Markush group was construed as being open due to the “at least one” claim language.

The court held that “[b]ecause the district court erred in its analysis of the binder in Amneal’s formulation, we vacate its finding that Amneal does not infringe the asserted claims because of the identity of Opadry. On remand, the court should consider whether Amneal’s formulation contains “from about 1% to about 5% by weight” of HPMC, irrespective of the HPMC’s pairing with PEG.”

Practice Points for Markush Groups:

- Take care to include all desired compounds in a Markush group

- Make sure that any compound recited in a dependent claim is also listed in the Markush group of the independent claim

Dependent Claim Invalidation

The court in Multilayer v. Berry also looked at the issue of whether a dependent claim is proper. 35 U.S.C. §112(d) states that:

(d) REFERENCE IN DEPENDENT FORMS.—Subject to subsection (e), a claim in dependent form shall contain a reference to a claim previously set forth and then specify a further limitation of the subject matter claimed. A claim in dependent form shall be construed to incorporate by reference all the limitations of the claim to which it refers.

MPEP 608.01(N) discusses dependent claims and covers rejections under 35 U.S.C. §112(d).

In Multilayer v. Berry, dependent claim 10 of the ‘055 patent was held invalid under 35 U.S.C. §112(d) because it recites low “density polyethylene homopolymers” which was not recited in the Markush group of claim 1, from which it depends.

Another case that looked at the issue of dependent claim invalidation is Pfizer, Inc. v. Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd., 457 F.3d 1284 (Fed. Cir. 2006). The patent at issue (US 5,273,995) was directed to atorvastatin, the active ingredient in Lipitor®. Dependent salt claim 6 was held to be invalid for failing to further limit its base claim; the base claim was not open to salts. The claims can be summarized/simplified as follows:

1. Compound A or Compound B; or pharmaceutically acceptable salt thereof.

2. Compound A.

6. The hemicalcium salt of the compound of claim 2.

Base claim 2 was not open to salts, and therefore dependent claim 6 was an improper dependent claim since it referred to a “salt.” Thus, Section 112, 4th paragraph is an independent ground for holding a patent claim invalid. Care must be taken when drafting a dependent claim, to ensure that the dependent claim specifies a further limitation of the base claim from which it depends.

More to Come

The fields of patent prosecution and patent litigation are ever-evolving, and with every new court decision there are lessons for patent practitioners. In future blog posts we will cover more claim drafting topics of interest, such as indefiniteness, product-by-process claims, means plus function claims and negative claim limitations.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 177220922

Author: microgen

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

6 comments so far.

Anon

December 23, 2022 12:56 pmIt is so – sorry that you may not like it, but you ARE doing the proselytizing that Efficient Infringers want you to be doing.

It’s not perfect, but abandoning the protection of patents is simply a non-starter.

Model 101

December 23, 2022 08:30 amAnon

Say it ain’t so!

Patents just tell your competitors how to do it.

Anon

December 23, 2022 07:40 am…and Model 101 jumps to the message that Efficient Infringers want you to think of.

That’s the way to fight them off.

Now where is my ‘sarcasm’ emoji…?

Model 101

December 22, 2022 03:09 pmGet with it

Claim construction is irrelevant under 101.

Also the Judges will find your patents ineligible for some other 101 reason.

Don’t waste your time or money on a patent.

Don’t be a fool.

Debora Plehn

December 22, 2022 10:47 amThank you Julie for pointing to other relevant MPEP sections that discuss Markush groups.

Julie Burke

December 21, 2022 07:33 pmThank you, Debora and Angie, for beginning this series of timely, practical articles. I am looking forward to your next installment. For this article, I’d like to add, in addition to MPEP 803.02, which covers election of species practice for Markush claims, rejections for non-statutory improper Markush groupings are covered in MPEP 2117 and definiteness/breadth of Markush claims is discussed in MPEP 2173.05(h).