“In typical antibody patents, an antibody derivative or bispecific antibody as a form of antibody is often described in the specification, not in the dependent claims.”

An antibody can take various forms, including the following: a monoclonal, polyclonal, mouse, human, humanized, monospecific, bispecific, glycosylated (sugar chain-modified), Fc-modified, or ADC (antibody-drug conjugate) antibody; an antibody fragment (e.g., Fab, scFv, diabody, sdAb, tandem scFv); or an antibody of different class or subclass (e.g., IgG (e.g., IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4), IgM, IgE, IgA).

An antibody can take various forms, including the following: a monoclonal, polyclonal, mouse, human, humanized, monospecific, bispecific, glycosylated (sugar chain-modified), Fc-modified, or ADC (antibody-drug conjugate) antibody; an antibody fragment (e.g., Fab, scFv, diabody, sdAb, tandem scFv); or an antibody of different class or subclass (e.g., IgG (e.g., IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4), IgM, IgE, IgA).

If claim 1 recites an “antibody”, whether or not the antibody includes each of the above forms can be an issue in an infringement lawsuit.

In Baxalta Inc. v. Genentech, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2020), Baxalta alleged that Genentech’s Hemlibra® (emicizumb-kxwh) product infringed its U.S. Patent No. 7,033,590 (’590 patent). In this lawsuit, the issue was whether or not the “antibody or antibody fragment thereof” in claim 1 of the ‘590 patent should comprise a bispecific antibody (the form of Hemlibra).

Here, claims 1 and 4 of the ‘590 patent are as follows:

1.An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

4. The antibody or antibody fragment according to claim 1, wherein said antibody or antibody fragment is selected from the group consisting of a monoclonal antibody, a chimeric antibody, a humanized antibody, a single chain antibody, a bispecific antibody, a diabody, and di-, oligo- or multimers thereof.

The United States District Court for the District of Delaware (the district court) adopted Genentech’s narrow claim construction (i.e., in the interpretation, the claim failed to include the bispecific antibody), and judged that Genentech did not infringe the ‘590 patent. However, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) vacated the district court’s judgment of non-infringement and remanded because the district court had erred in construing the terms “antibody” and “antibody fragment”. The CAFC’s grounds for negating the district court’s narrow construction involved the following:

(1) Claims

The dependent claim 4 recites “said antibody or antibody fragment (of claim 1) is selected from the group consisting of …, a bispecific antibody, …”. The district court suggested that the proper result here is “invalidation of the inconsistent claims rather than an expansion of the independent claims”. The CAFC, however, cited Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. T-Mobile USA, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2018) and rejected the district court’s construction, which rendered the dependent claims invalid.

(2) Specification

Column 5 of the specification contains sentences explaining the term “antibodies” in a narrow manner (i.e., in this construction, any bispecific antibody is not included), as follows:

Column 5 of the ‘590 patent

Antibodies are immunoglobulin molecules having a specific amino acid sequence which only bind to antigens that induce their synthesis (or its immunogen, respectively) or to antigens (or immunogens) which are very similar to the former. Each immunoglobulin molecule consists of two types of polypeptide chains. Each molecule consists of large, identical heavy chains (H chains) and two light, also identical chains (L chains).

The district court used this column 5 as the basis for interpreting that the “antibody or antibody fragment” does not include a bispecific antibody. The CAFC cited Budde v. Harley-Davidson, Inc. (Fed. Cir. 2001) and pointed out that “claim construction requires that we ‘consider the specification as a whole, and read all portions of the written description, if possible, in a manner that renders the patent internally consistent.’”.

(3) Prosecution History

In response to the Office Action regarding enablement rejection during examination, the “antibody or antibody derivative” of claim 1 was amended to read as “antibody or antibody fragment”. The district court’s judgement was that this amendment amounted to a disclaimer and the “antibody or antibody fragment” failed to include any bispecific antibody. In this regard, however, CAFC stated that there are no clear statements in the prosecution history regarding what scope, if any, was given up when the patentee substituted “antibody fragment” for “antibody derivative”.

According to the CAFC’s opinion, the description of the bispecific antibody in the dependent claim worked in patentee’s favor. Meanwhile, the term “antibody derivative” can encompass various forms of antibody, but an enablement rejection may be issued. Note that examples of the ‘590 patent describe the experimental results of derivatives (e.g., a chimeric antibody, antibody fragment) from a monospecific antibody, but no experimental results using any bispecific antibody are disclosed.

In view of such situations, this article shows the results of patent search from the following two aspects and discusses them while providing useful reference information for future patent practice:

(a) Is there any case (how many?) where an antibody derivative is allowed?

(b) Whether or not a bispecific antibody (or multispecific antibody) is recited in dependent claims of typical types of antibody patents (e.g., a patent based on the experimental results of monospecific antibody).

Search

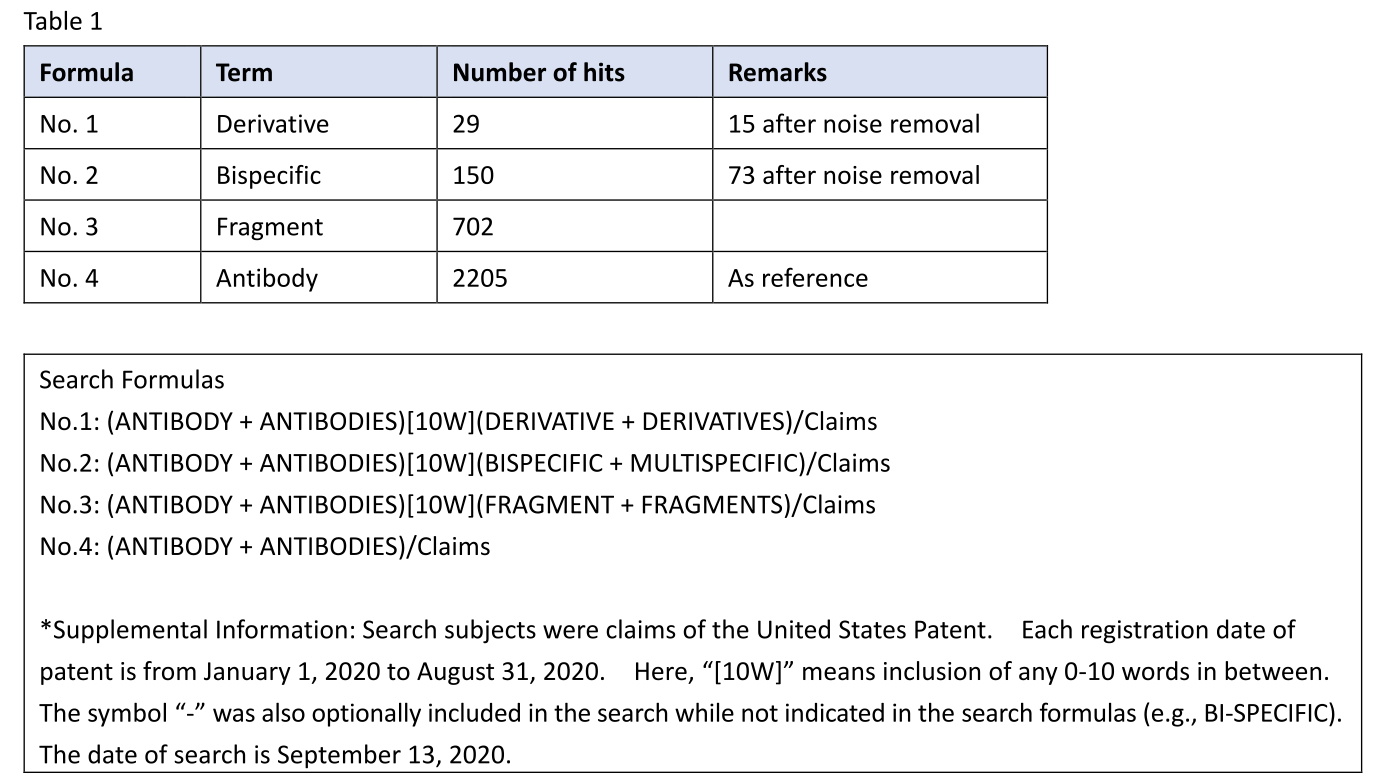

Claim Search

I retrieved U.S. antibody patents including an antibody derivative (No. 1) in claims and having a registration date from January 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020. Likewise, I also retrieved U.S. antibody patents including a bispecific antibody (No. 2) or an antibody fragment (No. 3) in claims. Because the antibody fragment often comes with the original antibody, as in the case of claim 1 of the ‘590 patent, the search term “fragment” was used as a reference term.

Table 1

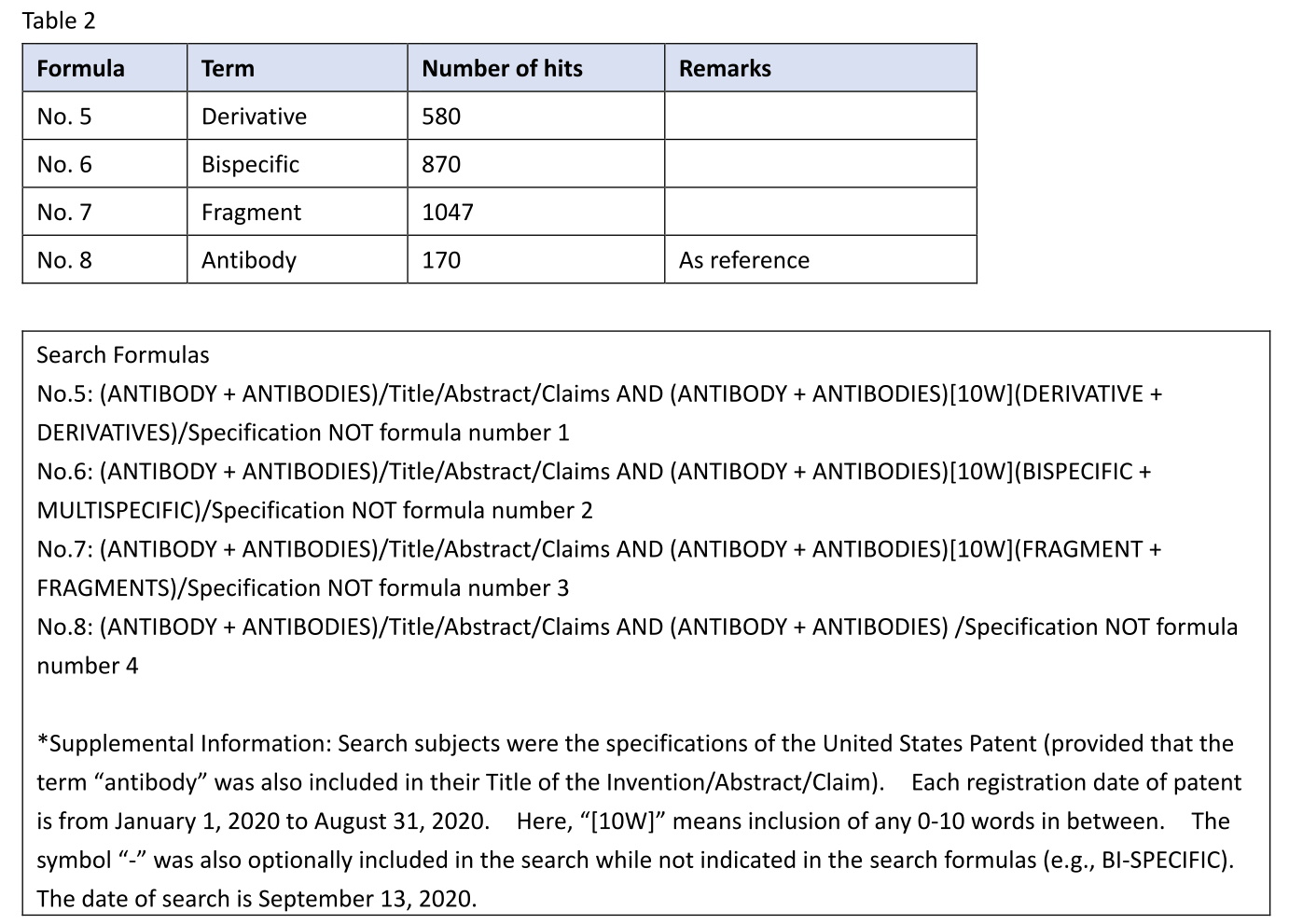

Specification Search

I retrieved U.S. antibody patents including an antibody derivative (No. 5) in the specification and having a registration date from January 1, 2020 to August 31, 2020. Likewise, I also retrieved U.S. antibody patents including a bispecific antibody (No. 6) or an antibody fragment (No. 7) in the specification. Note that the patents hit in the search of Table 1 were excluded from the results of this search. For example, in No. 5, the patents hit have no recitation of any antibody derivative in claims, but have a description in the specification.

Table 2

Additional Search

To check whether the tendency of the above search results was observed for another period, the corresponding patents were likewise retrieved while the registration date was changed to the period from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2019. As a result, there is a tendency similar to that of Tables 1 and 2 (the details are herein omitted).

In addition, the same search was repeated for patents in Japan or Europe, indicating that the total number of relevant patents is smaller than in the United States while there is also a similar tendency (the details are herein omitted).

Discussion

Antibody Derivative

For the term “antibody derivative”, 29 patents were hit by the claim search. The retrieved patents were individually reviewed, and 10 patents of patent search noise (e.g., a protein derivative) were found to be included. This may be because the term “derivative” is not specific to an antibody. In addition, 4 patents involve (are restricted to) a specific form of the derivative, such as a fragment or scFv. After these patents were excluded, the total number of patents having an antibody derivative in claims was reduced to 15 (e.g., U.S. 10,722,580, U.S. 10,556,950, U.S. 10,533,227). This number is about 1/47 of the number of patents having a fragment in claims. Thus, there are some cases where an antibody derivative has been patented, but the number is very low.

I also conducted, using the same search formulas and the same period of the registration date, another search of whether there was any patent in which an antibody derivative was recited in a patent application publication but not in the corresponding patent. As a result, 26 patent application publications (after noise removal) were hit and retrieved. The file wrappers of some of these patents were investigated. Then, 3 cases (U.S. 10,670,608, U.S. 10,648,984, and U.S. 10,570,196) were found to have an Office Action where a rejection (35 U.S.C. §112) with respect to the antibody derivative was issued.

Meanwhile, Japanese patents were likewise searched. The results have revealed 1 case (JP 6,639,392) of allowance (after the above noise removal) and 6 cases (JP 6,742,237, JP 6,732,041, JP 6,728,047, JP 6,685,225, JP 6,666,257, and JP 6,639,233) where a notice of rejection (Japanese Patent Law Section 36) was issued. Since there were only a few cases of allowance, I further searched for relevant patents registered in 2019. As a result, 9 patents (after noise removal) were found. Thus, there are some cases where an antibody derivative has been patented even in Japan, but the number is again very low.

Note that the JP patent (JP 4,313,531; the registration date: May 22, 2009) corresponding to the ‘590 patent includes an antibody derivative in claim 1. In Japan, a trial for infringement of the corresponding Japanese ‘531 patent by Hemlibra was instituted. However, the Intellectual Property High Courts in Japan rendered a decision of no infringement because Hemlibra “cannot be said to be understood or put into practice, based on the description of the present specification, by those skilled in the art” (October 3, 2019). At that time, the Intellectual Property High Courts in Japan stated that “a bispecific antibody should be construed to be included as a form of antibody derivative”.

By the way, in the specification search, 580 patents having an antibody derivative in the specification were hit and retrieved (e.g., U.S. 10,752,703, U.S. 10,738,123, U.S. 10,723,799). This number is about 1/1.8 of the number of patents having a fragment in the specification. This shows that, unlike in the case of claims, the term “antibody derivative” is often described in the specification.

Bispecific Antibody

For the term “bispecific antibody”, 150 patents were hit by the claim search. Each patent was briefly reviewed, and no search noise was found. This may be because the term “bispecific” is specific to an antibody. Among the 150 patents are 77 patents characterized by the structure or properties of bispecific antibody (i.e., a patent in which claim 1 sets forth a bispecific antibody, but not a monospecific antibody; a patent in which claim 1 sets forth two different antigens for one antibody; a patent in which the specification discloses the experimental results of bispecific antibody) (e.g., U.S. 10,544,187, U.S. 10,538,579). These patents are out of the scope of patent search subjects of interest, namely, “typical type of antibody patents” (see the above (b)), and are thus excluded. As a result, the number of relevant patents reached 73 (e.g., U.S. 10,544,226, U.S. 10,611,827, U.S. 10,745,470). This number is about 1/10 of the number of patents having a fragment in claims. In view of the above, among the patents based on the experimental results of monospecific antibody, it seems that there are relatively few cases in which a bispecific antibody is described in dependent claims.

I also conducted, using the same search formulas and the same period of the registration date, another search of whether there was any patent in which a bispecific antibody was recited in a patent application publication but not in the corresponding patent. As a result, 26 patents (after noise removal) were hit and retrieved. The file wrappers of some of these patents were investigated. Then, no cases were found to have an Office Action where a rejection (35 U.S.C. §112) with respect to the bispecific antibody was issued.

By the way, in the specification search, 870 patents having a bispecific antibody in the specification were hit and retrieved (e.g., U.S. 10,662,246, U.S. 10,654,929, U.S. 10,626,184). This number is about 1/1.2 of the number of patents having a fragment in the specification.

This shows that, unlike in the case of claims, the term “bispecific antibody” is often described in the specification. Note that the specification of each of the above 3 patents is described such that an antibody includes a bispecific antibody.

Antibody Fragment

For the term “antibody fragment”, 702 patents were hit by the claim search. The term “fragment” has thus been very often recited in claims. Except for cases where an antibody fragment is inapplicable to the invention (e.g., the invention in which the full-length antibody needs to be detected in blood), the applicant should consider setting forth a fragment in claims.

Describe in the Specification

The above search results suggest that, in typical types of antibody patents, an antibody derivative or bispecific antibody as a form of antibody is often described in the specification, not in the dependent claims.

As suggested by Baxalta v. Genentech, it was advantageous to set forth an antibody form of interest in a dependent claim. Meanwhile, patents in which an antibody derivative or bispecific antibody is set forth in a dependent claim are a minority among the patents searched in this case study. One of the reasons may involve avoiding a risk of rejection during examination.

As noted in the above point No. 2 relating to Baxalta v. Genentech, the CAFC considered the content of the specification for interpretation of claims. Accordingly, the disclosure in the specification is certainly important for construction of claims. In the results of this study, many patents have been found in which an antibody derivative or bispecific antibody is described in the specification. With respect to a form of antibody that an applicant wants to include in the scope of a patent, the applicant should consider describing in the specification that an antibody of interest includes the form of antibody.

Image source: Deposit Photos

Author exty

Image ID: 37242555

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.