“The court clearly drew the line on use of the utility patents at whether the trade dress elements were claimed in those patents or not.”

On June 12, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit decided Bodum USA, Inc. v. A Top New Casting Inc., No. 18-3030, 2019 (7th Cir. June 12, 2019). The case was based on Bodum’s allegation that A Top infringed Bodum’s unregistered trade dress in its Chambord® French press coffee maker design and squarely addressed the doctrine of “functionality” of trade dress. The court addressed two important issues related to functionality: (1) what type of evidence is necessary to prove functionality of a particular design and (2) under what circumstances are utility patents relevant to that analysis?

In Bodum, there was no dispute that the designs were similar (as shown below with the Bodum design on the left and the A Top French press on the right):

Evidence presented at trial established that Bodum has a long history of protecting the design of its Chambord® French press and advertising its distinctive features, namely, its metal cage, metal pillars ending in curved feet, C-shaped handle and domed lid topped with a spherical knob.

Evidence presented at trial established that Bodum has a long history of protecting the design of its Chambord® French press and advertising its distinctive features, namely, its metal cage, metal pillars ending in curved feet, C-shaped handle and domed lid topped with a spherical knob.

Trade Dress and Functionality

Trade dress, which is a variety of trademark protection, refers to a particular design or configuration (including packaging or the design of the product itself) that is so distinctive that consumers immediately recognize it as associated with a unique source. Trademark law is based on consumer protection laws. Thus, if a company markets a particular good or service (such as a French press coffee maker) in a way that confuses a consumer into believing that the good or service is that of someone else, such actions constitute unfair competition, and the action is one for trademark infringement. For any trademark infringement claim, a trademark owner needs to prove that it has a valid trademark (that is, that the mark is distinctive enough that consumers associate it with a single source), and that the accused mark is likely to cause confusion as to source. When the trademark is trade dress, there is an additional requirement to show infringement. Because trade dress applies to the configurations (e.g., shape) of a product, there is an additional requirement on the trade dress owner to prove that the trade dress is not “functional.” A trade dress is “functional” if it confers an unfair advantage in terms of cost or quality or would exclude others from competing for the same type of product. The distinction is necessary because functional innovations (i.e., what things do and how they work) can be protected only through the grant of a utility patent. Obtaining a utility patent requires the overcoming of significant hurdles, including proving that the functional innovation is both new (nobody has done it before) and not obvious (even if new, it would not have been obvious to do). If a person could obtain trade dress protection for functional designs, that person could obtain the equivalent of utility patent protection without meeting the stringent requirements for entitlement to a utility patent.

The tension between utility patent protection and trade dress protection is exemplified by the U.S. Supreme Court’s case, TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 28–29 (2001). In that case, the Court held that there is a rebuttable presumption that features of a design patent (which is very similar to trade dress protection in that it protects ornamental, nonfunctional designs) that are claimed in a utility patent are functional. Because of the close similarity between design patent protection and trade dress protection, the Seventh Circuit extended that same presumption to trade dress protection. Georgia-Pacific Cons. Prods., LP v. Kimberly-Clark Corp., 647 F.3d 723, 727–28 (7th Cir. 2011). Those cases were important aspects of the district court litigation between Bodum and A Top.

Establishing Infringement

To prove infringement in the case at hand, Bodum had to establish three elements: (1) it owned a valid trade dress in the Chambord® French press product, (2) the designs of the Chambord® French press and the A Top product were likely to cause confusion among consumers and (3) the trade dress of the Chambord® French press was not functional.

Bodum prided itself on the design of its products, including the French press coffeemaker trademarked as the Chambord ®. The Chambord ® French press was originally designed by a French designer, who took his inspiration from the tops of the towers of the Chateau Chambord, located in the Loire Valley in France. In 1991, Bodum purchased Martin SA, which owned the Chambord ® design. Since that time, Bodum alleged that it has grown the design into an icon and has been working to vigorously enforce its intellectual property “trade dress.” At trial, Bodum introduced the numerous design awards the Chambord ® has received, as well as the Chambord ®’s recognition by the Museum of Modern Art and multiple design publications (such as Phaidon Design Classics and Red Dot Design Yearbook) as “classic,” “legendary” and “timeless.”

Consequently, A Top did not contest likelihood of confusion or Bodum’s ownership of the trade dress. Instead, it contested only the functionality of the design.

A jury returned a verdict for Bodum, awarding $2 million in damages, which the district court doubled to $4 million for willfulness. On appeal, A Top made two arguments. It argued first that Bodum had not met its burden of proving non-functionality, and second that the district court had erred by excluding from evidence certain utility patents that would have established functionality.

The Seventh Circuit Steps In

The Seventh Circuit affirmed. On the burden issue, the Seventh Circuit faulted A Top for painting its functionality picture too broadly, focusing on the functionality of the elements themselves instead of the functionality of the actual designs. As the Seventh Circuit noted (with its emphasis):

Bodum does not claim that any French press coffeemaker with a handle, a domed top, or metal around the carafe infringes on its trade dress. Rather, it is the overall appearance of A Top’s SterlingPro, which has the same shaped handle, the same domed lid, the same shaped feet, the same rounded knob, and the same shaped metal frame as the Chambord, that Bodum objects to. Thus, to establish it has a valid trade dress, Bodum did not have to prove that something like a handle does not serve any function. It merely needed to prove that preventing competitors from copying the Chambord’s particular design would not significantly disadvantage them from producing a competitive and cost-efficient French press coffeemaker.

The court went on to cite the testimony of both parties’ experts that the particular elements of the Chambord® French press were not necessary to the design, or that alternatives would work just as well (if not better). The court also noted the testimony that the trade dress design did not confer an unfair advantage in terms of cost or quality (one way of determining whether a trade dress is functional). In fact, Bodum’s use of metal components and particularly shaped handle made the design more expensive than alternative French presses with feet, a cage, a handle and a domed lid. In other words, Bodum’s Chambord® design did not confer an unfair competitive advantage on Bodum, since other equally functional French press designs remained available, including ones at a lower cost.

The court next addressed A Top’s argument that the district court had erred by excluding utility patents that would have shown the trade dress to be functional. At trial, Bodum’s expert was asked whether certain utility patents disclosed the elements of Bodum’s trade dress. However, only portions of the patents were shown to the witness, consisting largely of pictures taken from those patents. The witness testified that he could not tell what were disclosed as important functional elements in the patents solely from pictures. What a utility patent actually protects as the functionality of the innovation is described in the claims and not in pictures. Because he understood the claims to be critical to the question of what aspects of those patents were functional, and he had been presented with pictures and not the patents’ actual claims, Bodum’s expert could not make an assessment of any functionality based on the patents A Top’s attorneys presented to him.

Upon objection, the district court excluded the patents as potentially confusing to a jury under Federal Rule of Evidence 403, which states: “The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice, confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.” The district court, recognizing that a utility patent can create a presumption of functionality, nevertheless limited that presumption to circumstances in which the utility patent claims the trade dress features in some “significant way.” The district court found that features at issue in the case were not claimed in the subject patents, elaborating as follows:

[T]here is a massive potential for jury confusion here if these things are used in the way, frankly, that they were used during the cross-examination of the [ ] expert. You put a picture up there, that’s got a handle, it’s got a knob, it’s got a plunger, it’s cylindrical like yours, that’s not what the inquiry is. The inquiry isn’t whether somebody has drawn this picture before. The inquiry is whether … the features are claimed in a patent in a way that shows that they have some sort of a function.

(quoting the district court).

In framing its analysis, the Seventh Circuit pointed out that the “patents A Top sought to introduce do not claim any of the features that comprise the claimed Chambord trade dress.” See TrafFix Devices, 532 U.S. at 29 (utility patents are evidence ‘that the features therein claimed are functional’ (emphasis added)).” The court further stated that the particular patents, which at least appeared to show “French presses with handles, domed lids, or knobs; are irrelevant to the legal question of functionality because the patents do not claim any of those features as part of the patented invention. Permitting the jury to view and consider the patents would cause confusion as to the appropriate inquiry for functionality.” (emphasis added). Finally, the court distinguished the case below (in which the district court properly excluded utility patents that did not claim the trade dress elements) from a prior case in which the court had reversed a district court that had determined on summary judgment that the feature claimed in the patent was not functional, saying that the matter of whether the claimed feature was part of the functionality or just “incidental” was a matter for the jury.

Impact for Future Trade Dress Cases

The case is most interesting because of the way the court handled the utility patent evidence. The decision indicates that the court clearly drew the line on use of the utility patents at whether the trade dress elements were claimed in those patents or not. Its language supporting the district court’s decision repeatedly made reference to the fact that the utility patents did not claim the particular elements of Bodum’s trade dress. Further, the court distinguished an earlier case in which utility patents were required to be considered by a jury based on the fact that the feature at issue there was in the claims. The court’s decision not only limits the applicability of utility patents in trade dress cases, it suggests that such patents may not even be admissible unless the party introducing those patents into evidence can point to the trade dress elements in the claims.

Editor’s Note: The author is an employee of Vedder Price, the firm that represented Bodum in this case.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

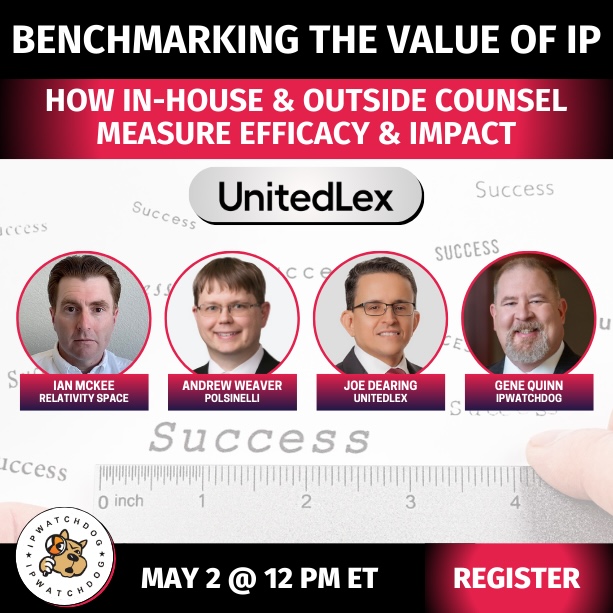

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Quartz-IP-May-9-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Daniel Shulman

August 8, 2019 02:24 pmJay, that’s literally what the Seventh Circuit says. Like you, I find the proposition a bit dubious since the claim defines the novel elements, but unclaimed subject matter can still be functional without meeting the novel and non-obvious threshold. Still, the court’s decision is the court’s decision, and at the very least it sets up the next dispute when a case comes along with a utility patent that’s more on point than the ones used here, i.e., when the actual item being litigated is covered by its own utility patent.

Jay Wells

August 8, 2019 09:01 amSeems merely to follow Traffix vis-a-vis claim language. Suppose the benefit of an element of the design is discussed in the patent specification, but is not claimed. Is the patent inadmissible as evidence?