“One reason for Bayh-Dole’s success is that the courts left it alone. The Federal Circuit wasn’t so fortunate.”

I recently visited Egypt as part of a team led by the Departments of State and Agriculture, supported by the good folks at the AUTM Foundation. Egypt, like many countries, is looking at our model for integrating research universities into their economy. I was asked to speak about the Bayh-Dole Act and thought it was important to emphasize that there were many factors required beyond enacting a law to reverse an entrenched national policy.

On returning, I was struck by Gene Quinn’s article, “It May Be Time to Abolish the Federal Circuit.” After leaving the Senate staff, I became Executive Director of the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO). Our highest priority was creating the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) to restore confidence in the U.S. patent system. Framed in my office is a very gracious thank you note from Judge Howard Markey, who inspired this effort and went on to become the first Chief Judge of the new court. Judge Markey was the only person I ever met with an unending supply of funny patent jokes, but that’s another story.

On returning, I was struck by Gene Quinn’s article, “It May Be Time to Abolish the Federal Circuit.” After leaving the Senate staff, I became Executive Director of the Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO). Our highest priority was creating the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) to restore confidence in the U.S. patent system. Framed in my office is a very gracious thank you note from Judge Howard Markey, who inspired this effort and went on to become the first Chief Judge of the new court. Judge Markey was the only person I ever met with an unending supply of funny patent jokes, but that’s another story.

Unlike Bayh-Dole, that effort appears to have gone off track. So why did one change stick and one not?

Ensuring Success

Many countries have enacted Bayh-Dole type laws only to find that a magical transformation doesn’t automatically take place. Implementing a policy changing long established norms is often more difficult than passing the law itself.

There were several critical factors which I discussed with the Egyptians as essential to Bayh-Dole’s success:

- The Supreme Court ruling in Diamond v. Chakrabarty and the creation of the CAFC restored confidence in the U.S. patent system;

- An effective Bayh-Dole oversight office fought off bureaucratic resistance; and

- The law has been implemented consistently so industry has confidence that the rules won’t suddenly change.

Let’s consider each point. The very first lines of the Bayh-Dole Act are: “It is the policy and objective of the Congress to use the patent system to promote the utilization of inventions arising from federally supported research or development….” Because federally supported discoveries are embryonic, they required significant investments of time and money from the private sector to turn them into useful products. The greatest impact of Bayh-Dole is in the life sciences, where these requirements are crucial and the odds against success the highest. Industry will not take these risks without strong, reliable patents.

During the Bayh-Dole hearings, we didn’t have any companies testify about the importance of working with universities. That changed after the Supreme Court held that a live, man-made microorganism could be patented. Stanford University and the University of California had discovered a recombinant DNA process and their patent application had been pending for years at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), which didn’t know what to do before the Supreme Court ruling. The highly effective Stanford licensing strategy for the Cohen-Boyer process put university technology transfer on the map. The U.S. soon seized the lead in biotechnology because of university/industry partnerships, and we’ve never looked back.

Because the Supreme Court then rarely heard patent cases (and now we appreciate how fortunate we were) the federal courts had adopted differing standards. Some circuits were pro and some anti patent. It was to end this uncertainty and to restore confidence in the U.S. patent system that Congress created the CAFC. As Gene chronicled, for many years it functioned as intended.

Leadership and Luck

The passage of Bayh-Dole, the Chakrabarty decision and the creation of the CAFC helped kick start the U.S. economy out of the doldrums of the 1970s. But another critical component was required—strong leadership ensuring that Bayh-Dole wasn’t strangled in its crib.

Senator Bayh was defeated before his law passed in a lame duck session of Congress, as was President Carter. That provided a golden opportunity for some bureaucrats, who resented losing power as Bayh-Dole decentralized technology management out of Washington, to undermine the new law through the implementing regulations. They would have succeeded but for one thing—there was someone overseeing Bayh-Dole who was a both a master of the subject and tough enough to prevail in interagency warfare.

Norman Latker (see “Remembering Norman Latker: The Passing of a Friend”) was the patent counsel at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He recognized in the 1960s that the policy of taking federally funded inventions from their creators and trying to licensing them non-exclusively wasn’t working. When President Johnson criticized NIH for not getting new drugs developed from its research, Latker helped create the Institutional Patent Agreements (IPA) whereby universities with a technology transfer capability could own and license their inventions. Licensing rates went from below 5% to 30% under the IPA. However, the Carter Administration wanted to re-establish micro-management and ended the program. The universities then approached Senators Bayh and Dole to reinstitute the IPA program across all agencies under force of law. This was the genesis of their legislation.

Latker was viewed as a problem in his agency, which tried to fire him. Bayh and Dole intervened, helping to relocate him out of NIH. When Latker moved to the Department of Commerce, Bayh-Dole placed its oversight function there.

The Department of Energy was opposed to decentralizing its tech transfer operations and urged President Carter to veto the new law. When that failed, they tried to control the regulations. Latker was fortunate because the Reagan Administration appointed Dr. Bruce Merrifield and Egils Milbergs, two entrepreneurs, to the Commerce Department leadership. They quickly realized the importance of Bayh-Dole and began building political support within the new Administration. Even so, it took a two-year, line by line battle to save the regulations. That culminated when President Reagan issued a Presidential Memorandum and later an Executive Order making Bayh-Dole the centerpiece of the Administration’s innovation policy.

After leaving IPO, I joined Norm at Commerce. When our office drafted and helped to enact the Federal Technology Transfer Act (Bayh-Dole for federal labs), Dr. Merrifield called us into his office when things were getting particularly sticky. He said: “Do what you need to do to get this passed. I’ve got your back.” He was true to his word and, once again, a critically needed bill got across the finish line.

Our string of luck continued as Deborah Wince-Smith replaced Merrifield when the George H.W. Bush Administration took office. Under her leadership, we were able to fight off efforts by the Department of State to undermine Bayh-Dole in international science and technology agreements (giving away our technology made other countries happy, so agreements were easier to complete). That fight went all the way to the White House, but once again the law came through unscathed.

If Bayh-Dole hadn’t had effective leadership in its early years, it never would have survived. Once it took root, it was strong enough to thrive after Norm and I had left—even when Commerce neglected its oversight duties for decades.

Numbers Don’t Lie

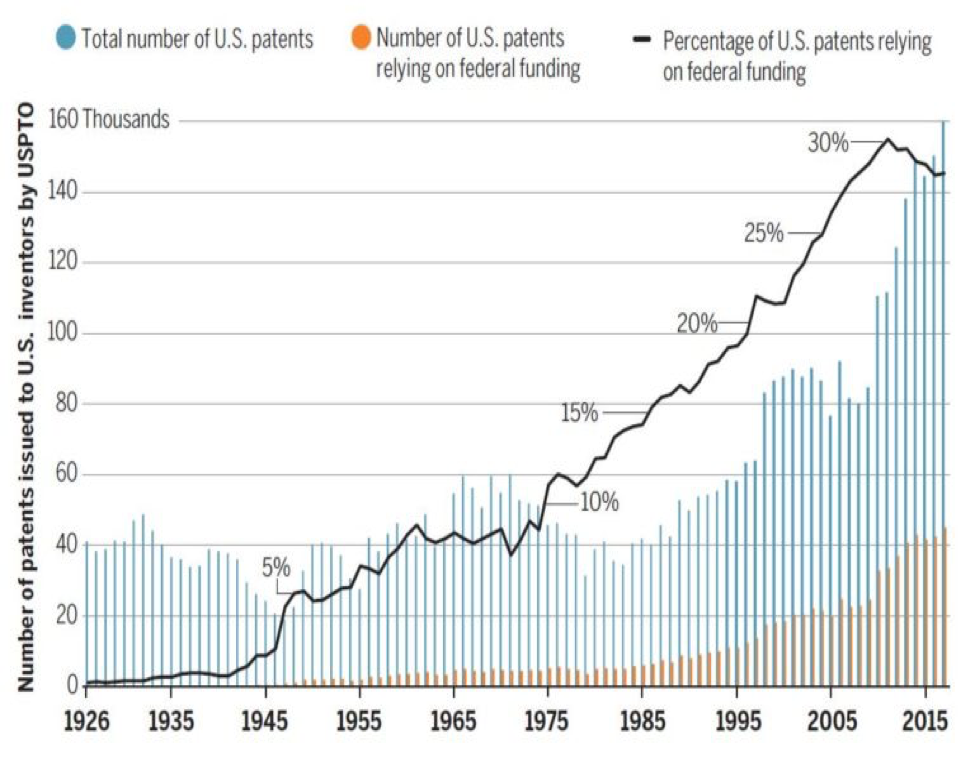

The synergy between Bayh-Dole and the patent system was brought home in a brand-new study titled “Government-funded research increasingly fuels innovation” in Science Magazine. It includes this chart, which I showed the Egyptians:

Before Bayh-Dole, the federal government funded approximately one half of all the R&D in the country. But the number of patents relying on federal funding was less than 10%. There’s a spike with the advent of the IPA program in the late 1960s, but that plunges when the Carter Administration halted it. The curve then takes off when Bayh-Dole passed in 1980. Today, the government only funds about 1/3 of the R&D in the U.S. but the number of inventions related to federal funding has grown to 30%.

One reason for Bayh-Dole’s success is that the courts left it alone. In the only case that rose to the Supreme Court, Stanford University v. Roche—while it’s reasoning wasn’t always clear—the decision left the law intact. The CAFC wasn’t so fortunate.

The Supreme Court issued a string of rulings casting doubt on the reliability and worth of U.S. patents. The CAFC was often overruled. While Bayh-Dole was strengthened by legislative amendments, the America Invents Act was another blow to the patent system. And as Gene chronicled, judges were appointed who seem to rule consistently against patent owners. That the CAFC is not what was originally envisioned shouldn’t be surprising, given its history.

Taking the Right Position

So, effective laws, coupled with effective leadership—and a little luck—makes all the difference. I don’t think Judge Markey would find much amusing about what’s happened to our patent system or to his court. But before we despair, we do have an effective champion at the USPTO under Andrei Iancu. If he’s given the required legislative tools, there is hope we can restore the U.S. patent system and resurrect Judge Markey’s vision for the CAFC. Perhaps we should invite the Egyptians over to remind us why they admire, and want to copy, our system.

P.S.: The pyramids and the Sphinx are well worth seeing. If you go, it’s worthwhile hiring a good guide. They can not only explain the significance of what you’re seeing, they can also position you on the cornerstone of Cheop’s Pyramid so you can get a picture like this:

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID: 169365156

Copyright: BrianAJackson

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Timothy Canter

August 15, 2019 04:02 pmOh, maybe because they are federally funded then your comment applies…

Timothy Canter

August 15, 2019 04:01 pmThank you! I understand your point but don’t believe that to be the case in this instance. The University claimed they were compelled by federal law to own the IP of any invention made during work on a SBIR – that the small business interest had no claim.

Joe Allen

August 15, 2019 03:55 pmTim: Bayh-Dole only applies when the university make an invention as a contractor/grantee with a federal agency. Bayh-Dole also applies to SBIR, assuring small companies they can own inventions the make with government dollars. In the situation you describe, it seem likely that there are other federal dollars on campus involved in the research beyond the SBIR dollars the company brought to the table. in which case universities typically file for title and give the company partner an appropriate license reflecting their investment in the project.

Tim Canter

July 25, 2019 10:47 amI’m begin told by a University that Bayh-Dole requires that they retain patent rights for anything invented at the University (or any other public institution) if the research is federally funded. More to the point, they claim this holds true even if the funding is via SBIR and a small business entity contracts with the University for some part of the research. Your description of Bayh-Dole was great – it helped me understand the importance of the law. However, can you please address my point because it seems either there is a second portion of the law that is less business friendly or I’m being misinformed.

Thank you!

Paul F. Morgan

July 20, 2019 12:27 pmAs noted before, if you had practiced patent law back when it was different in a dozen different circuits you would not be so eager to return to that by hoping to eliminate the Federal Circuit. Not even to mention that patent appeals are only part of its docket, and that most of what patent attorneys complain about is due to Congress or the Sup. Ct.