“The Second Amended Complaint reflects a substantial intersection of copyright and constitutional laws on issues that are far from settled, foreshadowing that, barring litigation settlement, we may someday see an Allen v. Cooper II Supreme Court decision.”

In Allen v. Cooper, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act of 1990 (CRCA) (codified at 17 U.S.C. §§ 501(a) & 511) did not abrogate a state’s sovereign immunity from copyright infringement liability. A casual reading of that decision might have led one to reasonably believe that it ended the plaintiffs’ copyright case. After all, the Supreme Court indicated that it affirmed a holding that the CRCA was “invalid.”

In Allen v. Cooper, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Copyright Remedy Clarification Act of 1990 (CRCA) (codified at 17 U.S.C. §§ 501(a) & 511) did not abrogate a state’s sovereign immunity from copyright infringement liability. A casual reading of that decision might have led one to reasonably believe that it ended the plaintiffs’ copyright case. After all, the Supreme Court indicated that it affirmed a holding that the CRCA was “invalid.”

But, as with so many other issues encountered in the legal realm, much lies below the surface.

The aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision cast light on the realization that the Court addressed only “prophylactic” abrogation, which seeks to deter constitutional harm before it occurs. On remand, the plaintiffs convinced the district court to consider whether the state’s sovereign immunity could be negated via a “case by case” type of abrogation, which requires actual violation of both a federal statute and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The district court thus reconsidered a previous dismissal of various claims and permitted the plaintiffs to amend their complaint “to buttress their allegations of ‘a modern form of piracy.’”

The plaintiffs did a whole lot of buttressing. Whereas their first amended complaint spanned only 24 pages listing five counts, their second amended complaint, served on February 8, 2023, spans 40 pages and asserts 10 counts. Their newest complaint thus basically doubles the length and the number of claims. It reflects a substantial intersection of copyright and constitutional laws on issues that are far from settled, foreshadowing that, barring litigation settlement, we may someday see an Allen v. Cooper II Supreme Court decision.

Recap of Pre-Remand Facts and Procedural History

The facts and Supreme Court decision in Allen v. Cooper have received thorough discussion in previous IPWatchdog articles, but a brief recap of the facts and procedural history provides context for understanding the latest developments.

In 1996, marine salvage company Intersal, Inc. discovered, off the North Carolina coast, a shipwreck of Queen Anne’s Revenge, the flagship of the most famous pirate in history: Edwin Teach, a/k/a Blackbeard. North Carolina contracted with Intersal to coordinate recovery activities. Intersal, in turn, retained Frederick Allen, a local videographer, to document the operation. Over the span of approximately 15 years, Allen created videos and photos of divers’ efforts to salvage artifacts and other remains of Queen Anne’s Revenge. Allen registered copyrights in those works.

Allen later discovered that North Carolina made unauthorized online postings of some of his videos and one of his photographs. In October 2013, Intersal, North Carolina’s Department of Natural and Cultural Resources (DNCR), and Allen (both individually and through his company Nautilus Productions, LLC (Nautilus)) entered into a Settlement Agreement to try to resolve various issues.

Allen characterized the Settlement Agreement as DNCR’s promise to not again use any of Allen’s footage for any commercial or promotional purposes without express permission. Shortly afterwards, North Carolina had what Allen called “buyer’s remorse,” which led to not only resumed unauthorized copying by the DNCR, but also to passage of a statute, namely, N.C. Gen. Stat. § 121-25(b), which Allen derisively coined “Blackbeard’s Law.” The statute proclaims that “photographs, video recordings, or other documentary materials” of shipwreck recovery efforts “shall be a public record.”

Allen and Nautilus (collectively, Allen) sued North Carolina, the DNCR, and various public officials (collectively, the State) in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina (EDNC), asserting in a First Amended Complaint (FAC) a declaratory judgment of unconstitutionality of Blackbeard’s Law, copyright infringement, a 42 U.S.C. § 1983 claim against the State for unconstitutional taking, unfair trade practices, and civil conspiracy. The State moved for dismissal on the ground of lack of standing as to the declaratory judgment action, and on certain immunities as to Allen’s remaining claims. In a 2017 order, citing abrogation of immunity by the CRCA, the EDNC refused to dismiss Allen’s copyright claim. It also refused to dismiss Allen’s declaratory judgment action, but it dismissed Allen’s remaining claims on various immunity grounds. The State then filed an interlocutory appeal.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed, indicating that it was bound by Supreme Court precedent on immunity as to patent infringement (Florida Prepaid) to rule that the CRCA was invalid. The Fourth Circuit remanded, instructing the EDNC to dismiss all claims without prejudice to the extent that Allen’s claims sued the State in their official capacities, and to dismiss with prejudice all claims against state officials in their individual capacities. The EDNC complied in an August 2018 order, and Allen obtained Supreme Court review, but only as to the CRCA abrogation issue.

In its March 2020 decision, the Supreme Court affirmed. It deemed Florida Prepaid dispositive in concluding that the Intellectual Property Clause (Art. I, § 8, cl. 8) did not constitutionally support the CRCA. The Court held that § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment also failed to provide constitutional support. Despite acknowledging that § 5 “allows Congress to ‘enact[ ] reasonably prophylactic legislation’ to deter constitutional harm,” the Court held that because legislative evidence did not demonstrate “a congruence and proportionality between the injury to be prevented or remedied and the means adopted to that end,” § 5 could not justify the CRCA.

The EDNC Revives Allen’s Constitutional Claims

In September 2020, on remand to the EDNC, Allen moved for reconsideration of the EDNC’s dismissal of his claim against the State under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for an unconstitutional taking. Allen argued that: (1) the Supreme Court only disallowed “prophylactic” abrogation by the CRCA, and did not decide whether sovereign immunity could still be abrogated by a “case by case” type of abrogation under United States v. Georgia, which permits abrogation upon establishing a violation of both a federal statute and the Fourteenth Amendment; and (2) due to an intervening 2019 Supreme Court decision (Knick v. Township of Scott), Allen was no longer required to first pursue a state law remedy as a prerequisite to lodging his § 1983 claim in federal court.

Agreeing with both points, the EDNC granted Allen’s motion in an August 2021 decision, held that the CRCA was still valid for “case by case” abrogation, ruling that Allen’s “takings claim and constitutional claims under Georgia are no longer dismissed,” and allowing Allen to amend the FAC.

The State appealed the EDNC’s order to the Fourth Circuit, and the EDNC stayed its proceedings pending that appeal. In October 2022, however, the Fourth Circuit dismissed the appeal for not being directed to a final order.

In an Order entered on January 18, 2023, the EDNC lifted the stay and ordered Allen to file an amended complaint within 21 days from the date of that order.

Allen’s Second Amended Complaint

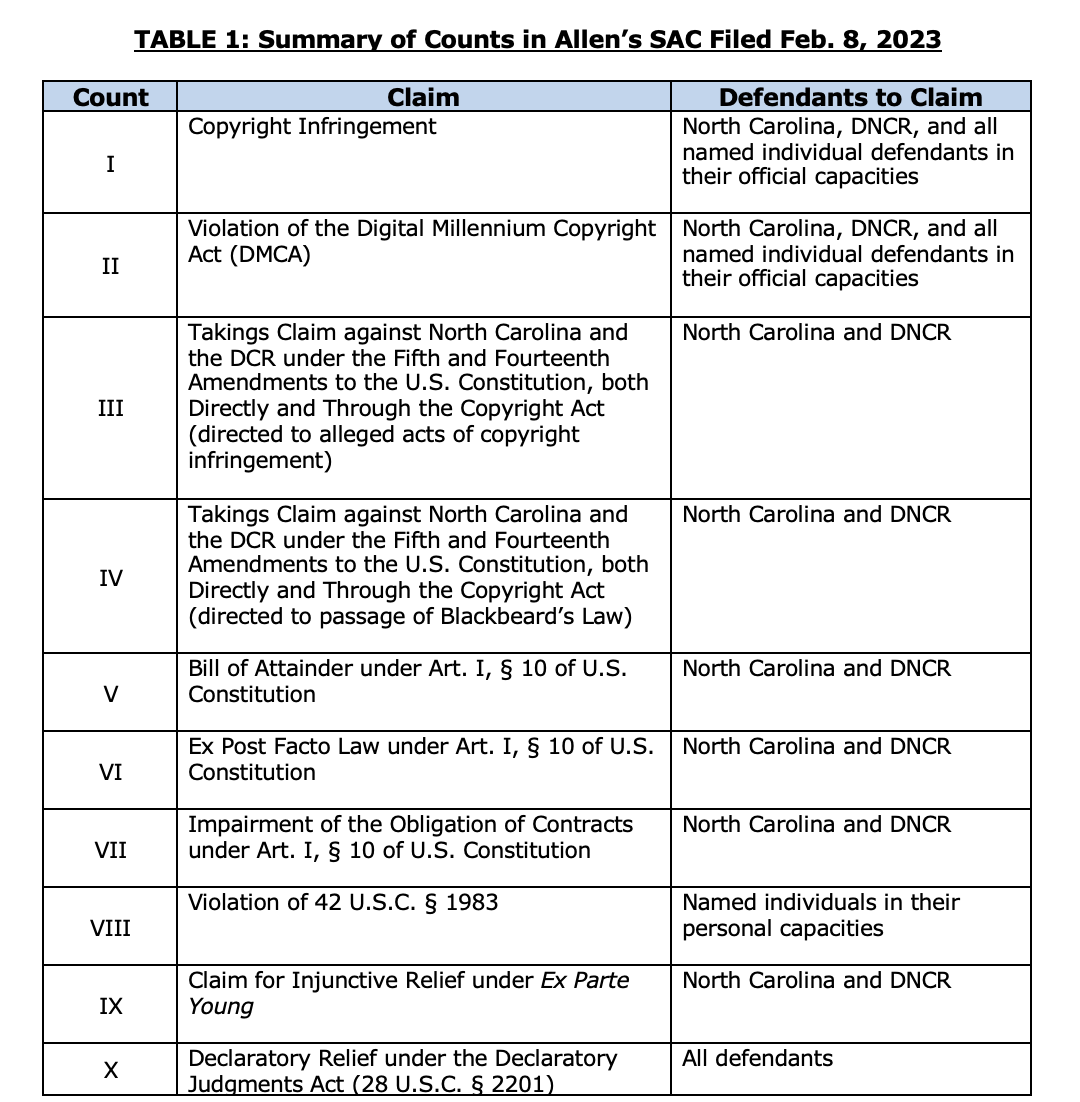

On February 8, 2023, Allen filed his Second Amended Complaint (SAC), significantly amplifying his allegations and reciting ten counts, summarized in Table 1 below.

Count I of the SAC adds 22 alleged instances of copyright infringement that occurred after passage of Blackbeard’s Law, eight of which are alleged to still be ongoing. Included among those were alleged showings of unauthorized copies of some of Allen’s videos in North Carolina’s Maritime Museum in Beaufort.

The newly-added Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) claim (Count II) alleges that the defendants removed copyright management information from their unauthorized copies of Allen’s works in the course of committing the accused acts of copyright infringement.

Counts III and IV independently assert claims under the Takings Clause, representing another change from the FAC, which only mentioned a takings claim in conjunction with the § 1983 count. In an August 2021 report titled Copyright and State Sovereign Immunity (at pp. 65-66), the Copyright Office observed that a Takings Clause theory addressing copyright infringement by a state “has rarely been tested, and the viability of such a claim remains uncertain. Copyright owners who have sought to bring takings claims have encountered difficulty establishing their basic elements.” On one hand, the Fifth Circuit observed that the Supreme Court has not yet recognized copyrights as a form of property protected by the Takings Clause. Can. Hockey v. Tex. A&M Univ. Ath. Dep’t, No. 20-20503, 2021 U.S. App. LEXIS 27012, at *22-*23 (5th Cir. Sept. 8, 2021) (nonprecedential). On the other hand, § 201(e) of the Copyright Act provides that, absent a prior transfer or bankruptcy, “no action by any governmental body or other official or organization purporting to seize, expropriate, transfer, or exercise rights of ownership with respect to the copyright, or any of the exclusive rights under a copyright, shall be given effect under this title.” In its 2021 Jim Olive Photography decision, the Supreme Court of Texas cited § 201(e) and stated: “The copyright owner thus retains the key legal rights that constitute property for purposes of a per se takings analysis, despite the government’s interference.”

Regarding Count V, also new to the case, ¶ 190 of the SAC states: “A bill of attainder is a statute or legislative act that inflicts punishment on specific individuals. See Nixon v. Adm’r of Gen. Servs., 433 U.S. 425, 473-74 (1977).” Count V then charges that Blackbeard’s Law is punitive and was specifically aimed at Allen, and requests revocation of Blackbeard’s Law, just compensation, and injunctive relief enjoining North Carolina from treating Allen’s works as public records.

New Count VI alleges that Blackbeard’s Law is an ex post facto law, prohibited by the Constitution, because it sought to punish Allen for conduct that predated the passage of Blackbeard’s Law. Count VI requests the same relief as in Count V.

New Count VII alleges that Blackbeard’s Law impaired the Settlement Agreement, in violation of Article I, § 10 of the Constitution, which reads in relevant part: “No State shall . . . pass any . . . Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts[.]”

Count VIII of the SAC reasserts the § 1983 claim previously pled as Count III of the FAC. However, Count VIII of the SAC provides more detail and specifically names state officials who purportedly personally participated in the acts that Allen characterizes as unconstitutional takings.

Count IX, also new to the case, seeks solely injunctive relief pursuant to Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908). As the Fourth Circuit’s Allen v. Cooper opinion stated: “Under Ex parte Young, private citizens may sue state officials in their official capacities in federal court to obtain prospective relief from ongoing violations of federal law.” Following its precedent, however, the Fourth Circuit held that Ex parte Young relief is only available where a party defendant has some connection with enforcement of the challenged law. It will remain to be seen whether Count IX will overcome that Fourth Circuit rule.

Count X is a recast declaratory judgment claim that originally appeared as Count I of the FAC. Count X now is not limited to Blackbeard’s Law but asks for declarations that the defendants are liable for the acts pled in the preceding counts of the SAC.

What Now Lies Ahead?

The EDNC granted the defendants an extension of time to answer the SAC, through March 23, 2023. It will be interesting to see how they respond to Allen’s amplified allegations and how the resurrected Allen v. Cooper litigation then progresses. The SAC raises issues that could very well chart a return voyage of Allen v. Cooper to the Supreme Court. The bench and bar would certainly treasure a meaningful review of those issues.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.