“As practitioners, we can settle into patterns of what we do, and we are not always in tune with whether that’s the most effective approach. While this data is not airtight…we can still gather insights from it to guide our practice.”

Lawyers should always be trying to look at things from new and different angles to gain an edge. We owe it to our clients, and honestly, we should do it for ourselves, because it makes practicing more fulfilling. In an effort to spice up my patent law life, I have become especially interested in patent analytics over the past few years—that’s right, I just used “patent analytics” and “spice up” in the same sentence.

Lawyers should always be trying to look at things from new and different angles to gain an edge. We owe it to our clients, and honestly, we should do it for ourselves, because it makes practicing more fulfilling. In an effort to spice up my patent law life, I have become especially interested in patent analytics over the past few years—that’s right, I just used “patent analytics” and “spice up” in the same sentence.

Language (Might) Matter

Due to this curiosity, I’ve spent a considerable amount of time playing around with patent analytics, using LexisNexis PatentAdvisor, over the last couple of years. I started by taking a look at Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) decisions for ex parte appeals through the lens of case law citations. Mainly, this was with respect to common arguments to rebut obviousness rejections. For one example, I’ve run reports regarding how often PTAB decisions mentioning “teach away” or “teaches away” led directly to a Notice of Allowance (only 18%). In another example, I tried the same with “non-analogous art” or “analogous art” and it did not fare much better (only 26%).

I then decided it would be interesting to take a look at language used in responses to Office Actions and tried to test out some conventional knowledge. Many patent attorneys have heard throughout their careers that using strong language in a response with an examiner is unhelpful. This led me to analyze responses that used the language “the Examiner asserts” in comparison to “the Office Action states.” Interestingly, conventional knowledge prevailed, and applications using the less argumentative language of “the Office Action states” in at least one response resulted in a 3.1% (81.1% v. 78.0%) higher allowance rate than “the Examiner asserts.”

It is, of coursenot possible to prove causation by these numbers alone, and there are certainly other factors involved. But, knowing this, is there any reason to use “the Examiner asserts”? In my opinion, there is really no downside to switching to “the Office Action states,” although it would seem not to be a factor in most patent applications

The ‘Prima Facie Case of Obviousness’ Debate

This made me wonder whether advantages of a less combative approach extended to other aspects of responses. Obviousness, which is often the determinative issue for patentability, is inherently subjective. However, case law and the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) have plenty of guardrails to limit hindsight bias analysis and to ensure there is an adequate reason to combine references. Prosecuting patent applications at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), I have commonly attacked rejections by stating the requisite burden examiners must meet to establish a prima facie case of obviousness and arguing that the Examiner has not met this burden.

Patent attorneys have differing opinions regarding whether examiners should be called out if an Office Action is deficient in providing a factual basis establishing obviousness, or if the reasoning lacks a rational underpinning. In my practice, I am often aggressive in addressing such deficiencies, but I try to balance this based on my clients’ preferred strategy and will often interview with the examiner if the circumstances suggest it would be beneficial.

As practitioners, we can settle into patterns of what we do, and we are not always in tune with whether that’s the most effective approach. With this in mind, I wondered if attacking a rejection from this perspective was generally hurting or helping my clients, taken as a whole. To analyze this, I used PatentAdvisor’s File Wrapper search and searched responses to Office Action filed with the USPTO that used the language “prima facie case of obviousness.” I assumed that if this language was mentioned, the applicant was arguing that the examiner had not established a prima facie case of obviousness. Patent lawyers do not use this language to congratulate the examiner for establishing a prima facie case of obviousness. No examiner has ever read, for example, “[i]t is respectfully submitted that the Examiner has eloquently established a prima facie case of obviousness.”

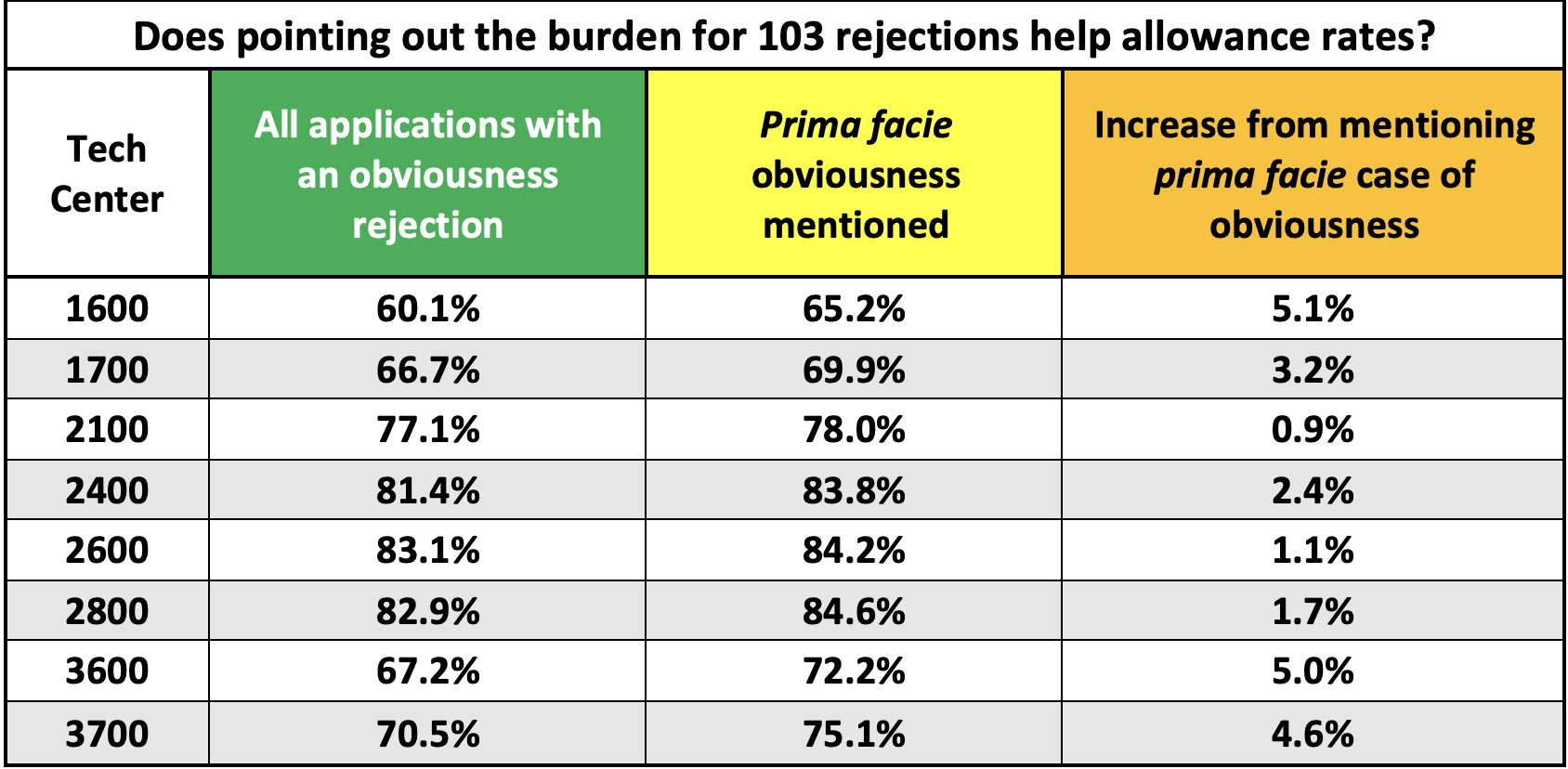

After obtaining the results for “prima facie case of obviousness,” I then narrowed the results to applications disposed (patented or abandoned) since 2019 and sorted by technology center for allowance rates and Office Actions per patent and compared these results to the average allowance rates in each technology center for disposed applications during this same time period that included an obviousness rejection.

The results show that arguing the Examiner has not established a prima facie case of obviousness is not detrimental in any of the technology centers in terms of allowance rate. In fact, it is beneficial for increasing allowance rates, especially in technology centers having the lowest allowance rates.

Technology centers 1600, 1700, 3600 and 3700 are the most difficult tech centers at the USPTO and arguing that the Examiner has not established a prima facie case of obviousness results in the biggest jumps in allowance rates in these art units. In contrast, in the easier technology centers, 2100, 2400, 2600 and 2800, bringing up a prima facie case of obviousness still appears to have a minor benefit, but not as much as the more difficult art units.

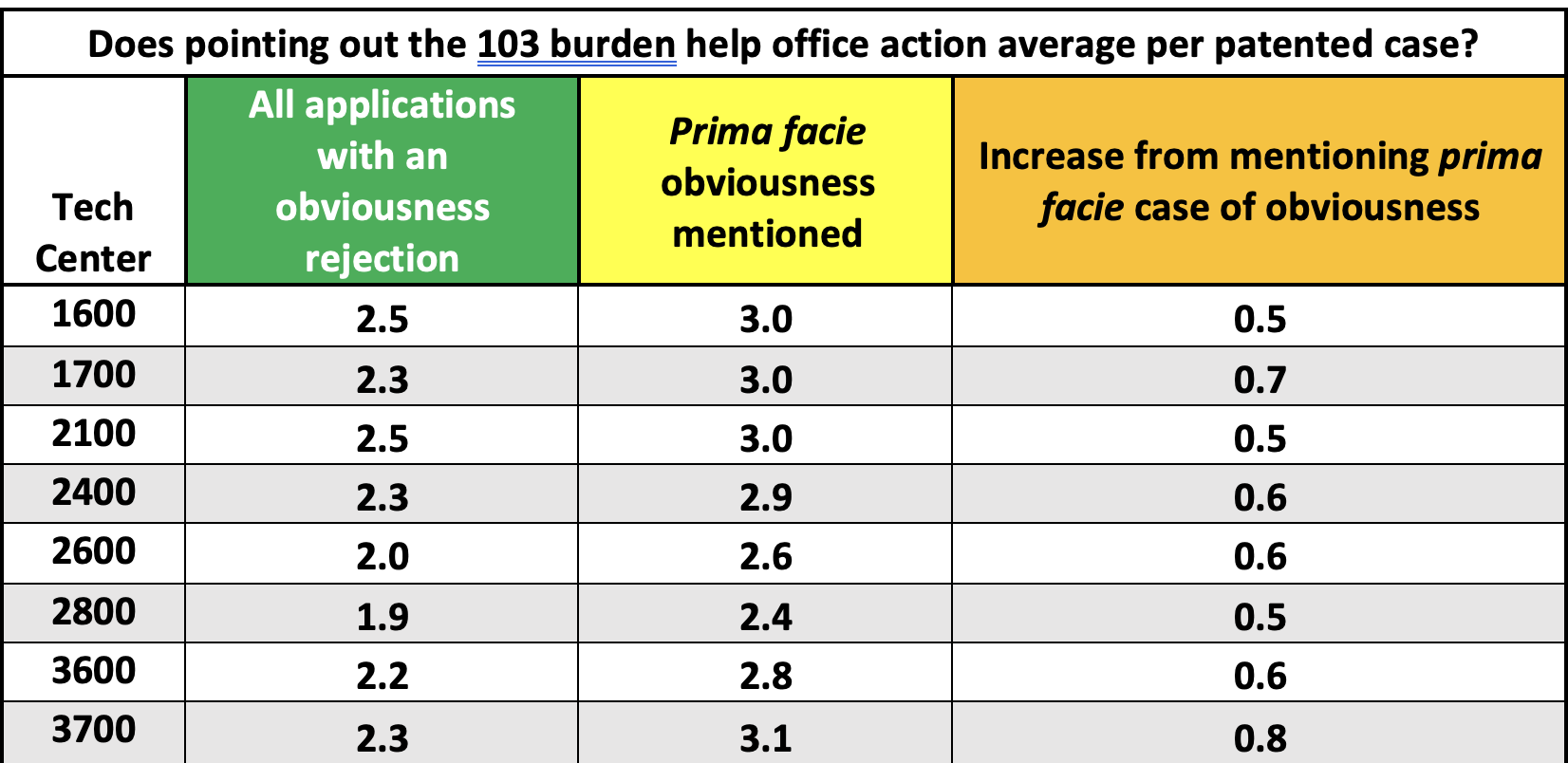

However, analytically speaking, there are downsides to arguing that the Examiner has not established a prima facie case of obviousness. In particular, as shown below, on average, challenging the Examiner in a such a manner can lengthen prosecution to a degree. For cases including responses that mentioned “prima facie case of obviousness” there was a higher number of Office Actions issued by patented case. In particular, there was an increase of between 0.5 and 0.8 Office Actions per patent, depending on the art unit.

This is certainly only a small glimpse of data (I hope that we soon all have much more data within our grasps), but it implies to a degree that arguing the Examiner has not established a prima facie case of obviousness can increase the number of Office Action responses filed.

However, it says nothing about claim scope or other arguments presented. I would presume that arguing the examiner has not established a prima facie case of obviousness results in less narrowing amendments than the average response. It shows a resistant response, and resistance logically correlates to arguing a rejection without amending the claims. In other words, it shows an applicant who genuinely believes the examiner is wrong and is not going to narrow the scope of protection to appease the Examiner.

If the subject matter of a patent application is important, it certainly makes sense to spend extra resources fighting tooth and nail for claim scope. That’s a no brainer. But if an application is less important, a more deferential approach can be helpful. I’ve always thought that one of the most unique aspects of patent prosecution is the ability to pull out your aggressive lawyer approach selectively, balanced with a technical mind for problem solving and wordsmithing claim scope to thread the needle.

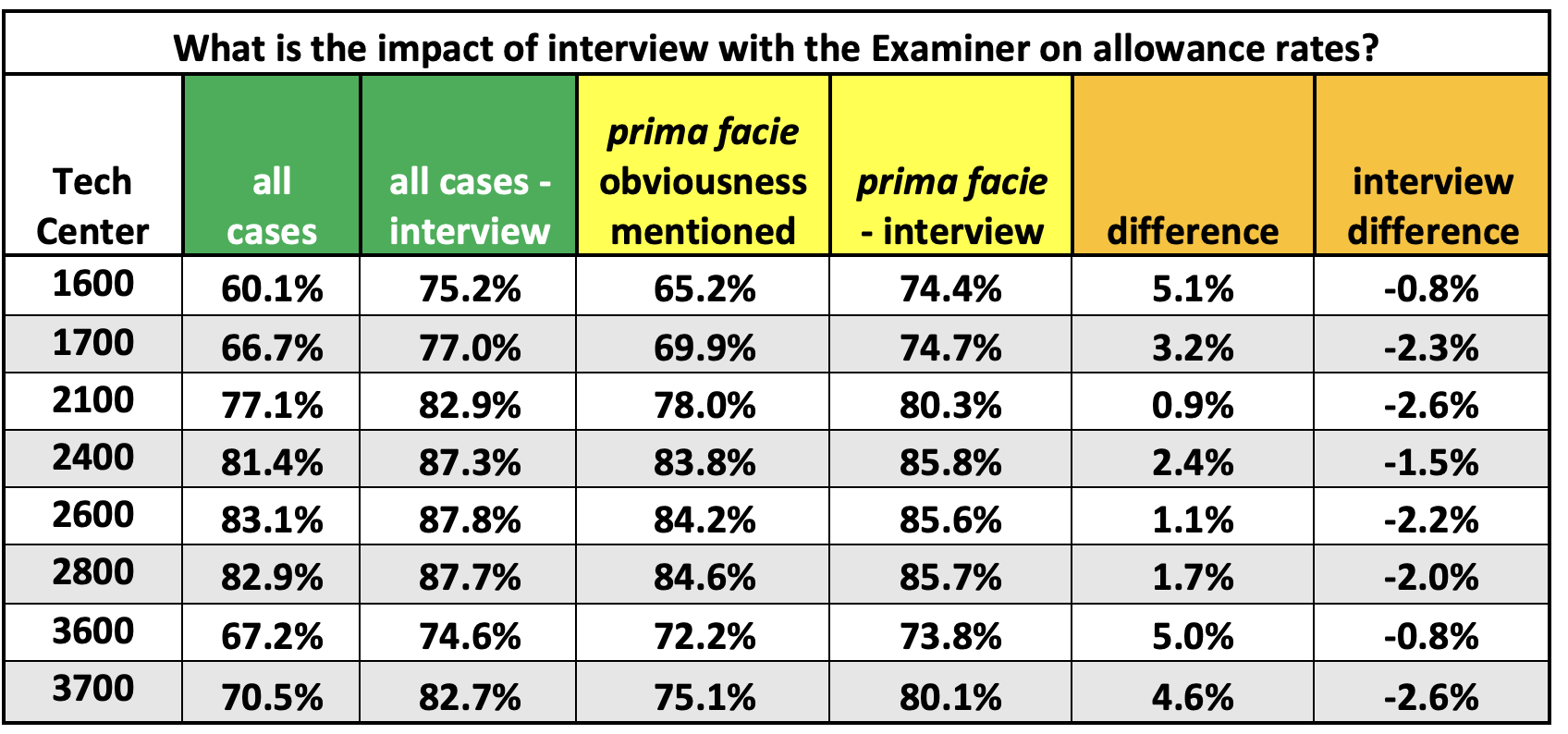

When in Doubt, Interview

But a different look at the data, as shown below, illustrates that interviews will bump your allowance rate up further. Regardless of whether or not you are arguing burden, it will pump up the allowance rate. This data also shows that there is place for calling out the examiner for not meeting the Section 103 burden AND reaching out to the examiner in a deferential manner. They are skills we all have to balance as patent attorneys. We need to figure out the limits of what the examiner will allow with a combination of technical and legal dialogue. We cannot settle for scope that is unhelpful to our clients but we also cannot waste a client’s money by unnecessarily fighting over trivial language.

Consider All the Angles

While this data is not airtight and could certainly be picked apart by a statistician, we can still gather insights from it to guide our practice. First, fighting back against difficult and/or inexperienced examiners is not without value. Second, fighting back in the wrong cases can be unhelpful. Third, always try to interview if you think there is any chance of reaching an agreement with the examiner.

Most importantly, thinking about prosecution from different angles is bound to pay off in the long run.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image Author: Rawpixel

Image ID: 126977324

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

3 comments so far.

Peter Kramer

October 6, 2022 11:00 pmWhat kills me is when an examiner retorts in an Advisory Action that the rejection was based on prima facie evidence despite that my rebuttal, which never stated the rejection lacked prima facie evidence, and further with the examiner never responding to my arguments made in rebuttal.

Julie Burke

October 5, 2022 09:35 pmThank you, Clint, for sharing this fascinating approach, delving into the intersection of carefully curated text searches combined with quantitative examiner analytics. Your article is thought provoking.

Chris H

October 5, 2022 10:54 amClint,

I love what you are doing with using analytics as a tool to “Moneyball” patent prosecution strategies.

The topic of using prima facie language in responses makes me wonder about correlation vs. causation. For example, does adding the prima facie language really result in higher allowance rates or are these cases where the Examiner did a poor job initially in rejecting the claims because prior art does not exist (or the search costs of finding prior art is too high), which are the cause of the higher allowance rates? Also, if an Examiner did a poor job rejecting claims by not providing adequate prior art or not addressing all of the claim limitations, does it not follow that prosecution would lengthen as a result of the Examiner needing another Office Action to correct their error? I believe you began allude to all of this when talking about amendment scope.

Also, I know of practitioners that use the term “prima facie” in boilerplate language at the beginning of their §103 rejections. I was wondering if these responses were filtered out. And it would also be interesting to see how the numbers change for Final vs. Non-Final as well as if the Examiner is a Primary Examiner.

Keep up the awesome work.