“There are at least some that believe the Federal Circuit is maybe over-interpreting Mayo not in line with some of the Supreme Court decisions.” – June Cohan, USPTO

June Cohan

June Cohan, Senior Legal Advisor in the Office of Patent Legal Administration at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) today explained to attendees of an event about the Office’s patent eligibility guidance that there are no plans to revise the guidance in light of the denial of certiorari in American Axle. She also acknowledged several areas of “divergence,” or “outlier cases,” between the USPTO and the U.S. Court of Appeals for Federal Circuit (CAFC) approaches to determining patent eligibility which the Office has no plans for revising, despite the fact that the CAFC is the reviewing court for the USPTO.

Bad Odds

Cohan told attendees that, since 2012, following the Mayo decision, the CAFC has issued over 190 written decisions on patent eligibility and only about 20% of those have saved at least one claim. Life sciences patents have fared better, with about 30% of decisions in that area finding at least one claim eligible. Lab methods, cryopreservation, methods of making a pharmaceutical and methods of treatment have all been treated well, with seven cases identifying eligible claims. Device claims have odds of about 50-50, while claims involving detecting or diagnosis have terrible odds—the CAFC has struck down all such claims that it’s seen since Mayo, Cohan said.

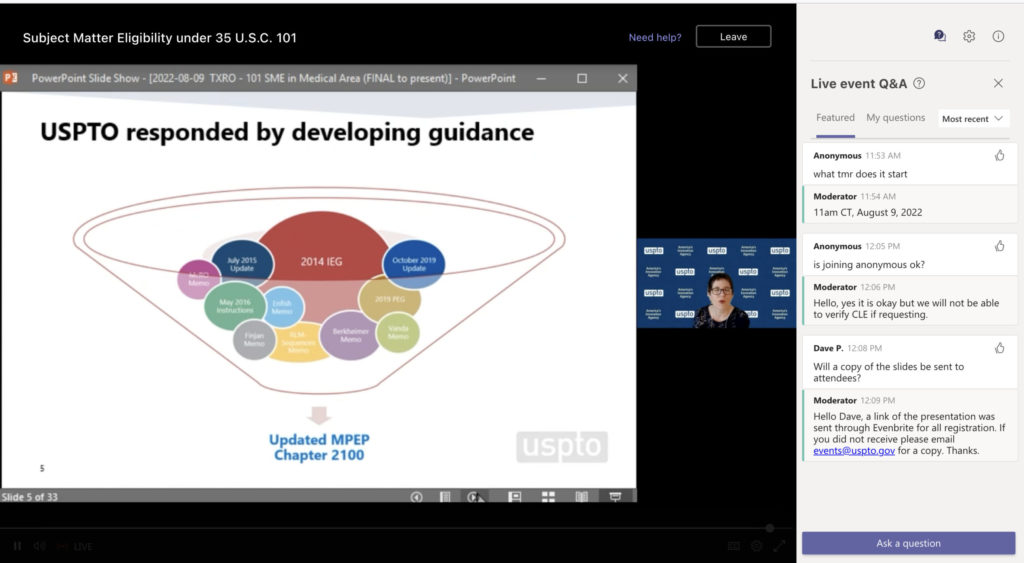

While the Supreme Court’s decisions in Bilski, Myriad, Alice and Mayo fundamentally changed the way the Office examines patent applications, patent owners are still more likely to have luck at the USPTO. Following those decisions, the Office worked on guidance with stakeholders and examiners and ultimately arrived at the present eligibility guidance, now codified in MPEP Chapter 2100. The guidance differs from the CAFC’s approach in a few ways, such as the determination of what qualifies as a law of nature, for example, which “has gotten a lot of flak from the courts,” Cohan said. She explained:

We created this by going back to Supreme Court cases like Mayo, studying very carefully the type of claim language that the Court identified as being a law of nature and then we wrote claims that didn’t include that type of language, and then we issued patents in accordance with this guidance, to stakeholders including Cleveland Clinic and Stanford University. But when those patents subsequently got reviewed by the CAFC, the court declined to follow the guidance and held some of them ineligible.

Cohan pointed to Cleveland Clinic Foundation v. True Health Diagnostics and CareDx, Inc. v. Natera, Inc. as examples of this discrepancy. In the Cleveland Clinic case, the Federal Circuit commented on the USPTO’s guidance, explaining:

“While we greatly respect the PTO’s expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to natural laws and those directed to patent-eligible applications of those laws, we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.”

However, as this was only a comment, the USPTO did not consider it necessary to revise its guidance in any way to comport with the Federal Circuit. “We follow the same body of precedent, but certain cases do appear to be outliers,” added Cohan. “There are at least some that believe the Federal Circuit is maybe over-interpreting Mayo not in line with some of the Supreme Court decisions.”

Cohan also noted that the Office’s addition of a prong 2 in the Step 2A analysis in 2019 also differs from Federal Circuit precedent. Following public feedback and internal studies, there seemed to be too much emphasis on the role of conventionality in the eligibility analysis, and so the Office went back to the Supreme Court cases and came up with the additional prong, which Cohan calls a “diet Step 2B,” as it uses all the same considerations as Step 2B except for “well understood, routine and conventional,” which she said makes a big difference. Cohan added that this prong has greatly improved consistency in rejections, taking the Office from a 25% rejection rate on eligibility in 2018 to about 8% today, and has also improved allowance rates in certain areas hard hit by the four big Supreme Court eligibility decisions. “We’re in a stronger place with an improved allowance rate as a result,” she said.

No Need for Change Following American Axle

When asked about whether the Office planned to update its eligibility guidance somehow in response to the denial of cert in American Axle, Cohan said that, while the Office supported granting cert and diverged from the Federal Circuit’s approach there as well, the most recent iteration of the guidance came out after the decision issued and “the denial doesn’t really add anything to it.” Three of the four seminal cases on eligibility were unanimous, and since the court still has a majority from the Mayo and Alice cases, “they probably haven’t changed position,” she noted. But Cohan said that the Office’s views were outlined fully in the Solicitor General’s brief in the American Axle case and implied that the writing is on the wall as far as whether the Office thinks the court should change its tune. She concluded:

We issued those patents, they’re presumed to be valid, we did not change our guidance in response to the decision in 2019, so I think that gives you an indication….We are obligated to follow the body of precedent form the Federal Circuit but there are outlier cases, and American Axle might be one of those.

However, USPTO Director Kathi Vidal did announce last month that the Office is soliciting comments on the current eligibility guidance through September 15, 2022, in anticipation of potentially revising the 2019 guidance.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

9 comments so far.

Loozap

August 12, 2022 04:59 amI agree with her with American Axe

concerned

August 11, 2022 02:41 pmAnon:

As you well know, not only does the examiner show no evidence to support their rejection, the examiner will not look at the inventor’s evidence that proves the process is not routine, not conventional or not well understood.

Of course no penalty to the examiner for doing whatever, yet the inventor has to continue to fight and spend money for the examiner’s lack of evidence and failure to acknowledge evidence on record.

Anon

August 11, 2022 12:50 pmAs to:

“Cohan also noted that the Office’s addition of a prong 2 in the Step 2A analysis in 2019 also differs from Federal Circuit precedent. Following public feedback and internal studies, there seemed to be too much emphasis on the role of conventionality in the eligibility analysis, and so the Office went back to the Supreme Court cases and came up with the additional prong, which Cohan calls a “diet Step 2B,” as it uses all the same considerations as Step 2B except for “well understood, routine and conventional,” which she said makes a big difference.”

Cohan should most likely have been reigned in on this “spin,” as this it nothing more than a “saving grace” for examiner’s in view of the Berkheimer case, and the fact of the matter that showing – to a required APA level – “conventionality” at both a single item, but more importantly as an ordered combination IS well above the capabilities of most all examiners.

As a reminder: this requires MORE than any mere prior art showing under either of 102 or 103, and requires the Office to show (with evidence) that the both single and ordered combinations are in well-known use in the industry.

Granted, this “wrinkle” was created by the courts (who will engage more latitude in their hand-waving). Regardless though of what the courts may or may not do, the Office does NOT have that same latitude.

Anon

August 11, 2022 11:16 amNice point mike – and so very true that our form of government is set up such that ALL THREE BRANCHES are below the Constitution.

Way too often, people (and oddly, attorneys, who really should take a better look at their state oath) tend to treat the Supreme Court as if it were above the Constitution (and that there were no checks and balances that could apply).

mike

August 11, 2022 07:37 amthe PTO — like all government agencies — owes its fealty to SCOTUS.

False. The PTO and all government agencies owe their fealty to the Constitution and the People.

Anon

August 10, 2022 11:12 amHmm,

A MAJOR point here that has been missed is that the USPTO cannot create guidance for its examiners that would deal with the divergence from the CAFC

because the CAFC is divergent from itself.

And this is directly due to the Supreme Court being divergent from itself.

By this, I mean the well-known Gordian Knot created and now massively rolled up in that decisions simply contradict other decisions.

The (easy!) solution (that is not so easy to implement) is to CUT the Gordian Knot.

Hence, my prior offerings of the Kavanaugh Scissors (recently augmented with the Barret pivot).

Night Writer

August 10, 2022 04:42 amI agree with her with American Axel. We know that the Scotus is getting closer to looking at 101 again but that’s all we know from the denial of cert.

I generally agree with this that I take to mean that the CAFC case law is so inconsistent that we don’t really know what 101 means anymore.

concerned

August 10, 2022 03:46 amPro Say:

I have to disagree in part.

There is no explanation for some of the behavior I have witnessed from the USPTO.

I see no evidence that SCOTUS said routine, well understood and conventional to mean nobody on Earth has ever used the process. There is no legal reason to compel the USPTO to write or imply the same.

I see no legal reason from the USPTO to discard evidence. The USPTO own MPEP states I have a right to establish a prima facie case. Curious is 100% correct when he states the USPTO does not use evidence, the USPTO uses analysis. Yet Alice relied on evidence going back to the 1890s. What SCOTUS decision said evidence is irrelevant?

My first IPWatchdog article back in 2018 stated that official USPTO memos only seemed to serve some kind of official capacity. Those official memos were not applied to my prosecution.

Whether a person agrees that a patent should be granted, certain principles should be readily apparent in all legal settings. Both my attorneys have argued that those principles have not been applied to my application. In fact, my current attorney B is arguing that the USPTO and its Board had no authority to ignore SCOTUS guidance.

I am so thankful that I am a “one and done” inventor. Fortunately I do not have the brains to come up with a second invention to even be tempted to file another patent application.

Pro Say

August 9, 2022 09:34 pmThe bottom line is this:

While it is of course true that the CAFC is the PTO’s reviewing court, the PTO — like all government agencies — owes its fealty to SCOTUS.

It’s called Supreme for a reason.

That some of the CAFC judges refuse to accept and abide by SCOTUS’ very narrow, cabined limits on eligibility (creating an incomprehensible morass of legal and factual gobbledygook in the process) is, in the final analysis, of no matter.

The Patent Office is correct to look to SCOTUS for its eligibility guidance.

Even though SCOTUS usurped the exclusive Constitutional authority of Congress in the process.