“The CAFC acknowledged that the Board’s analysis ‘may not be a model of clarity,’ but added that it doesn’t require ‘perfect explanations’…. “[W]e may affirm the PTAB’s findings ‘if we may reasonably discern that it followed a proper path, even if that path is less than perfectly clear.’”

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) on Tuesday affirmed a Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) ruling that Samsung Electronics had failed to prove certain claims of Dynamics, Inc.’s patent for a magnetic stripe emulator that communicates with credit card readers unpatentable as obvious.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) on Tuesday affirmed a Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) ruling that Samsung Electronics had failed to prove certain claims of Dynamics, Inc.’s patent for a magnetic stripe emulator that communicates with credit card readers unpatentable as obvious.

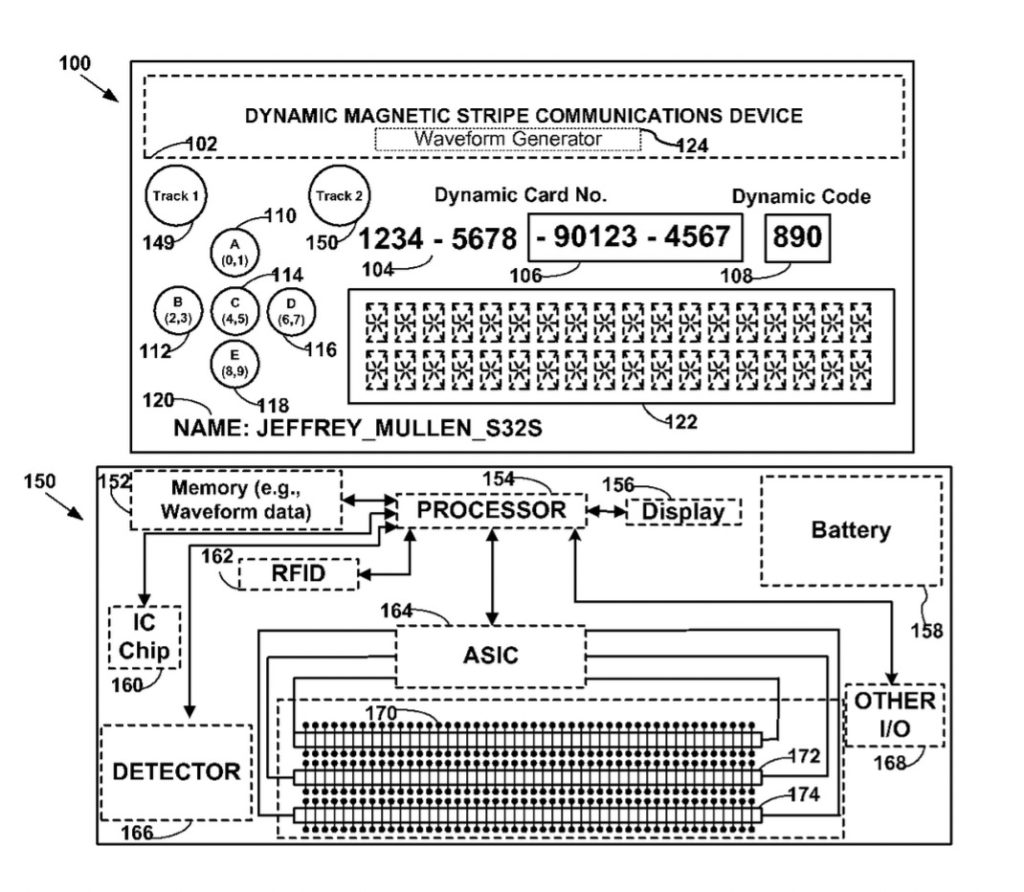

Samsung petitioned the PTAB for inter partes review (IPR) of claims 1 and 5-8 of U.S. Patent No. 8,827,153. The patent is directed to “magnetic stripe emulators” for “generat[ing] electromagnetic fields that directly communicate data to a read-head of a magnetic stripe reader,” such as the magnetic stripes on credit cards. Samsung argued that the claims would have been obvious over U.S. Patent No. 4,868,376 (Lessin) and U.S. Patent No. 7,690,580 (Shoemaker), or alternatively, would have been obvious over U.S. Patent No. 6,206,293 (Gutman) in view of Shoemaker.

Motivation to Combine Arguments Fail

Samsung said the combination of Lessin and Shoemaker disclosed claim 1’s “wherein limitation,” which reads “wherein said device is operable to retrieve said digital representation from a plurality of digital representations of said at least one track of magnetic stripe data.” Specifically, Samsung said that Shoemaker disclosed “a plurality of digital representations of one or more tracks of magnetic stripe data.” On appeal, Samsung argued that the PTAB failed to address the argument that one of the ways in which Shoemaker disclosed this plurality of representations was “by teaching the communication of forward- and reverse-oriented track data depending on the direction its card is swiped (directional representations).” In failing to address this argument Samsung also said the PTAB violated the Administrative Procedures Act (APA).

The CAFC did not agree, saying that Samsung was “simply incorrect” that the Board did not address this argument. “Not only did the Board acknowledge the argument…it expressly found that ‘[d]espite [Samsung’s] . . .argument that Shoemaker discloses a card emulating the same track data regardless of directionality, we find the record does not support [its] contention,’” wrote the CAFC.

During oral argument, Samsung attempted to assert that the PTAB’s decision failed to adequately analyze the directional representations instead, but the CAFC said this argument was forfeited because it was not adequately raised in Samsung’s opening brief. “While Samsung’s opening brief alludes in passing to an alleged lack of clarity in the Board’s analysis, those statements cannot fairly be read in context to have raised any argument in the alternative,” explained the court. That criticism was instead made to support Samsung’s contention that the Board had failed to address the argument concerning Shoemaker’s directional representations.

Ultimately, the PTAB’s finding that Shoemaker does not read on the claim limitation because “when its card determines swipe direction it then represents or encodes the data on the dynamically reconfigurable data interface so that the data stream is always provided in the experienced order irrespective of the swipe direction,” and its subsequent holding that the combination of Lessin and Shoemaker therefore did not demonstrate that a skilled artisan would have been motivated to combine the references, “charts a clearly discernable path.” The CAFC did acknowledge that the Board’s analysis “may not be a model of clarity,” but added that it doesn’t require “perfect explanations,” citing In re Nuvasive, Inc, in which the court held that “we may affirm the PTAB’s findings ‘if we may reasonably discern that it followed a proper path, even if that path is less than perfectly clear.’”

The CAFC next agreed with the PTAB that a skilled artisan would not have been motivated to combine Gutman in view of Shoemaker. Samsung said that the combination of these two references teach the wherein limitation of Claim 1 of Dynamics’ patent, arguing that a person skilled in the art “would have been motivated to modify Gutman to incorporate the directional representations of Shoemaker into Gutman’s memory” in order to improve the technology. But the PTAB, and on appeal, the CAFC, said that Samsung’s argument failed in that it did not make clear how altering either reference from its original would improve functionality or how this combination would be more commercially convenient for customers.

No Legal Error

The court also rejected Samsung’s contention that the PTAB legally erred in “1) requiring Gutman or Shoemaker to provide an express motivation to combine, and (2) the Board erred by reversing Samsung’s proposed obviousness combination, treating Shoemaker as the primary reference to be modified in view of Gutman.” The court said the Board considered Samsung’s proposed motivations to combine, rather than requiring an express motivation to combine, and that its second argument was grounded in a single sentence made by the Board while ignoring the remainder of the decision. “[T]he Board found that Samsung’s proposed modification of Gutman amounted to the combination of ‘disparate parts of the prior art’ without a sufficient explanation as to why a skilled artisan “would have chosen the specific features relied upon by [Samsung] to read on the claim,’” said the court. “That reasoning was not legal error.”

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.