“As the USPTO bound itself to treat requests for Director’s review under the rehearing regulations, it is bound to treat requests for Director’s review of decisions on institution just as it treats such requests for reviewing Final Written Decisions.”

Scott R. Boalick, Chief Administrative Patent Judge speaking at the USPTO Boardside Chat on the Director Review process in July 2021.

Since the Supreme Court decision in United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021), there has been much discussion about the Court’s ruling mandating an option for users to request that the Director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) review Final Written Decisions of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) rendered in trials under the America Invents Act (AIA) on the validity of issued patents. But there has been little or no discussion on such Director’s review of PTAB decisions on institution of AIA trials.

The AIA assigned the decision whether to institute Inter Partes Reviews, (IPR)—the most common type of AIA trials—to the Director, not to the PTAB. See 35 U.S.C. § 314(a) (“The Director…authorize[s] an IPR to be instituted”); § 314(b) (“The Director shall determine whether to institute an [IPR]…”); § 314(d) (referring to “[t]he determination by the Director whether to institute an [IPR]” as being “final and nonappealable.”). In § 314(d), Congress vested substantial and exclusive power with the Director by precluding judicial review of the Director’s decision on institution in any Article III court. The Supreme Court found “‘clear and convincing’ indications … that Congress intended to bar review.” Cuozzo Speed Techs., LLC v. Lee, 279 136 S.Ct. 2131, 2140 (2016) (quoting Block v. Community Nutrition Institute, 467 U.S. 340, 349–350 (1984)); Thryv, Inc. v. Click-To-Call Techs., 140 S. Ct. 1367, 1372 (2020) (same).

A nonappealable decision on institution of an AIA trial is a final decision binding the Executive Branch, as the Director “has arrived at a definitive position on the issue that inflicts an actual, concrete injury.” Darby v. Cisneros, 509 U.S. 137, 144 (1993). Whether or not the decision on institution is correct, it is irreversible and there is “actual, concrete injury” to the losing party in the decision on institution. First, to the patent owner, a decision to institute results in the high expense of the proceeding and the loss of the presumption of patent validity under 35 U.S.C. § 282. See e. g., Vtech Comm. Inc. et al. v. Shperix Inc., IPR2014-01432, Paper 47 at 10 (PTAB, Feb. 3, 2016) (“[T]here is no presumption of validity in an [IPR], and, therefore, we will not be applying a rule of construction with an aim to preserve the validity of claims.”). As such, the patent owner loses quiet title as the patent becomes unenforceable against any other party. Upon assertion of the patent in district court, such party could initiate an IPR by identically copying the successfully-instituted IPR petition against that patent and seek a stay. Courts grant a stay in about four out of five cases in which a patent is subject to an IPR. Second, to the petitioner challenging the patent, the Director’s decision to deny institution is the end of the road at the PTAB, foreclosing on any possible relief at the PTAB for cancelling invalid patent claims.

As a final agency decision unreviewable by the courts that concretely affects property rights, the Director’s decision whether to institute an AIA trial is quintessentially one to be made by a principal officer—a person who is Presidentially-appointed, and Senate-confirmed. In United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021), the Supreme Court held that “the unreviewable authority wielded by [administrative patent judges] APJs during [IPR] is incompatible with their appointment by the Secretary to an inferior office. . . . Only an officer properly appointed to a principal office may issue a final decision binding the Executive Branch in the proceeding before us.” Id., at 1985. Accordingly, as the Arthrex Court held, a Director’s review of PTAB decisions must be available, Id., at 1988, including for decisions on institution.

A search in the PTAB database for AIA trials reveals that there were 84 IPRs subject to requests for Director’s review following Arthrex in which orders were entered as of December 8, 2021. All were requests for review of the Final Written Decisions (82 denials were summarily denied using an identical single terse sentence without giving any reason or explanation for denying the review and only two requests were granted with explanation and remand to the Board). Perplexingly, none requested Director’s review of Board decisions on institution. Nevertheless, I explain here why such Director reviews should be available immediately after PTAB decisions on institution of AIA trials.

1) The law enunciated in Arthrex compels the availability of Director’s review of PTAB decisions on institution.

The USPTO Director delegated by regulation to the Board the authority to decide whether to institute AIA trials. 37 C.F.R. § 42.4 (“The Board institutes the trial on behalf of the Director.”). Although the Director delegated the pertinent duty of performance to the Board, the Director necessarily retains the non-delegable duty of supervision and control over such Board decisions. See Restatement (3rd), Agency, §§ 7.06, 7.07 (under common law, a principal that has a duty to protect others continues to hold that duty, even if performance is delegated to an agent). For example, the Director has a non-delegable duty to provide “management supervision for the Office” and ensure Board action in a “fair, impartial, and equitable manner.” 35 U.S.C. § 3(a)(2)(A). Indeed, the Supreme Court in Arthrex held that “the exercise of executive power by inferior officers must at some level be subject to the direction and supervision of an officer nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate.” Arthrex, 141 S. Ct. at 1988. Therefore, Arthrex compels the availability of the Director review of the Board decisions on institution just as it does for the Board’s Final Written Decisions.

That the Arthrex decision text arguably subsumes within its scope, and certainly does not exclude, the Board decisions on petitions to institute AIA trials, is also manifest in the Court’s choice of the word “petition:” “The appropriate remedy,” the majority opinion explained, “is a remand to the Acting Director to decide whether to rehear the petition filed by Smith & Nephew.” Id. at 1987 (emphasis added). The term “petition” in the IPR statute is used only in connection with institution: “a person who is not the owner of a patent may file with the Office a petition to institute an [IPR],” 35 U.S.C. § 311(a); § 311(d) (“The Director shall determine whether to institute an [IPR] pursuant to a petition.”) (Emphasis added). Under the statute, the “petition” is clearly directed and structured only for institution of an AIA trial, as the petition’s content must show only “a reasonable likelihood that the petitioner would prevail,” § 314(a), whereas once an IPR is instituted, “discovery of relevant evidence” is included, § 316(a)(5), and “the petitioner shall have the [higher] burden of proving a proposition of unpatentability by a preponderance of the evidence,” § 316(e), to prevail in the Final Written Decision. There is no petition directed to issuing “a final written decision with respect to the patentability.” § 318(a).

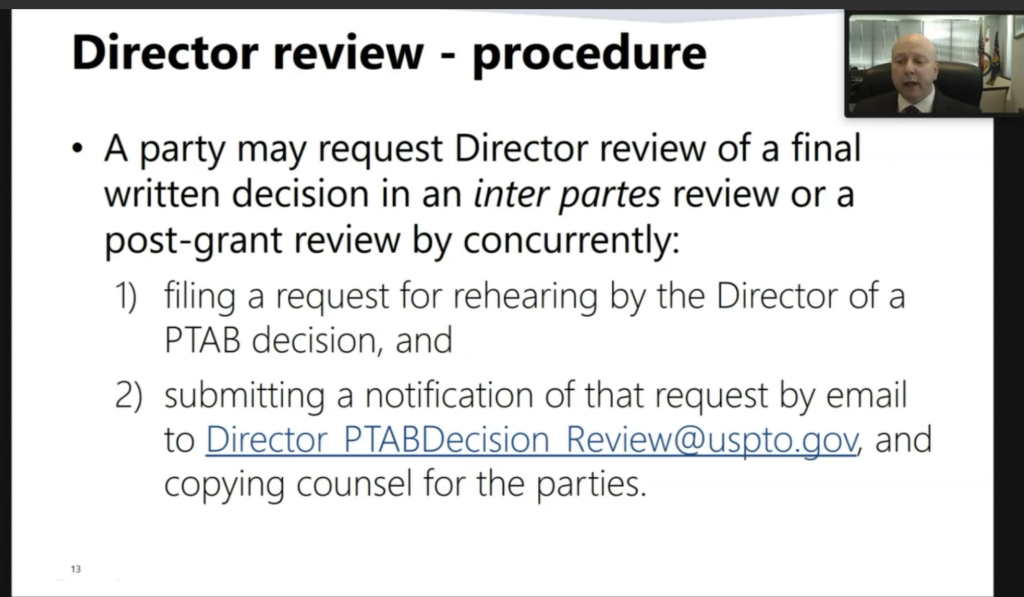

2) The USPTO adopted regulations governing Director’s review that expressly authorize review of Board decisions on institution.

The USPTO declined to promulgate (even emergency) regulations to govern requests for Director’s review of Board decisions. Instead, as “interim Arthrex procedures,” the USPTO adopted for that purpose its existing regulations—those in “the current rehearing procedures under 37 C.F.R. 42.71(d),” wherein “[t]he filed Request for Rehearing by the Director must satisfy the timing requirements of 37 C.F.R. 42.71(d),” and wherein a “timely Request for Rehearing by the Director will be considered a request for rehearing under 37 C.F.R. 90.3(b).” Arthrex Q&As No. A2 (updated July 20, 2021). These existing rehearing regulations apply equally to Board decisions on institution of an IPR and on Final Written Decisions on patentability. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.71(d), subparagraphs (1) (Requests must be filed within 14 days of the entry of a non-final decision or a decision to institute a trial); or (2) (Within 30 days of the entry of a final decision or a decision not to institute a trial).

The USPTO’s rule of procedure thus reasonably interprets the Director’s review requirement in Arthrex as applicable to both Board decisions on institution and to Final Written Decisions. As the USPTO bound itself to treat requests for Director’s review under the rehearing regulations, it is bound to treat requests for Director’s review of decisions on institution just as it treats such requests for reviewing Final Written Decisions—as these rehearing regulations require. “[I]t is elementary that an agency must adhere to its own rules and regulations. Ad hoc departures from those rules, even to achieve laudable aims, cannot be sanctioned, for therein lie the seeds of destruction of the orderliness and predictability which are the hallmarks of lawful administrative action.” Reuters v. FCC, 781 F.2d 946, 950-51 (D.C. Cir. 1986). Although the PTO’s Arthrex Q&As on the internet only mention Final Written Decisions, they do not set any exception, nor do the underlying regulations permit the PTO to disparately reject requests for Director’s review of decisions on institution. Roberts v. Vance, 343 F.2d 236, 239 (D.C. Cir. 1964) (any exception to agency’s own procedural regulations must exist as an explicit writing, by an official having sufficient authority to do so).

3) Standards of Review

Under the USPTO’s interim Arthrex procedures, Director review of a Board decision is properly sought to evaluate, among other things, “material errors of fact or law,” “matters that the Board misapprehended or overlooked,” “issues on which Board panel decisions are split,” or “novel issues of law or policy.” Arthrex Q&As No. D2 (updated July 20, 2021). The Director is to review the Board decision “for an abuse of discretion,” 37 C.F.R. §42.71(c), wherein the review is de novo. Arthrex Q&As No. A1 (“Director’s review may address any issue, including issues of fact and issues of law, and will be de novo.”) Finally, the Director’s review must be in writing and cannot be an unreasoned summary dismissal or denial with no support or explanation. See details in the answer to Question #1: Can the Director summarily dismiss requests for review, analogously to FRAP 36?.

Acceptance of the Request is Not an Option

Because the availability of Director’s review of PTAB decisions on institution is compelled by Arthrex, and is expressly provided for by USPTO regulations, the Director must accept requests for review of decisions on institution.

This article was last updated on December 17, 2021.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

4 comments so far.

Ron Katznelson

January 29, 2022 06:27 am“Patent Rule,”

Your use of the term “final agency action” is a red herring when it comes to “finality” of a discrete agency action, as your analysis ignores the Supreme Court’s case law I cite. You construct a strawman fallacy, saying: “[a] decision to institute (or not to institute) does not resolve any issue, dispose of any property right, or otherwise affect the parties in any way the law recognizes.”

First, a PTAB decision on institution actually “resolves an issue” –- the important and tangible issue of whether or not a trial on the merits will commence, with all its consequential effects on both parties. Second, “dispos[al] of any property right” is not, and cannot be, the criterion for finality. Rather, “concrete injury” of any type is the criterion cognizable under the law: “the finality requirement is concerned with whether the initial decisionmaker has arrived at a definitive position on the issue that inflicts an actual, concrete injury.” Darby v. Cisneros, 509 U.S. 137, 144 (1993). And contrary to your contention, a decision that “inflicts an actual, concrete injury” would actually “affect the parties in [a] way the law recognizes.”

The “concrete injury” often inflicted on patent owners immediately after a PTAB decision to institute is real. Post-institution loss of clear title and the presumption of validity is often manifested by:

(i) Loss of commercial opportunities, identifiable disruption of regular business, or forced reorganization;

(ii) Licensee stopping payments, or holding off negotiations;

(iii) Infringers avoiding response or refusing to negotiate;

(iv) Forcing a patent owner’s decision to hold-off on patent enforcement;

(v) Losing potential investors’ interest; or

(vi) Losing strategic partners’ or product distributors’ interest.

See descriptions of post-institution “concrete injuries” suffered by some of the inventors whose stories are reported at http://usinventor.org/inventors. As explained above, and contrary to Patent Rule’s flawed legal argument, upon a showing of actual “concrete injury,” the courts would likely compel the USPTO to accept requests for Director review of PTAB decisions on institutions.

Patent Rules

January 20, 2022 08:16 amI think the strength of your argument turns on whether an institution decision is a “final agency action.” Rather than address that question you merely presuppose its answer in the fourth paragraph of your essay. A decision to institute (or not to institute) does not resolve any issue, dispose of any property right, or otherwise affect the parties in any way the law recognizes. It does not even prevent the petitioner from filing another petition. An institution decision does not appear, to me, to bear any hallmark of a final agency action. Thus I see no basis to compel extension of Arthrex to institution decisions.

Ron Katznelson

December 15, 2021 02:17 amAnon,

I agree with your take. It does not matter what type of property or tangible interests are to be protected — Arthrex holds that taking those away irreversibly requires at least supervision and control of a Presidentially-appointed Senate-confirmed officer.

Anon

December 14, 2021 05:16 pmInteresting views on Agency.

I would also call into that same sphere of thought the notion that must inure from the Oil States decision: if indeed patents are going to be treated as a form of personal property known as “Public Franchises,” then Agency/Franchise considerations must also come into play, including those duties owed by a FranchisOR to a FranchisEE.