“Judge Moore’s dissent poignantly identifies that ‘[t]he majority’s true concern with these claims is not that they are directed to Hooke’s Law…, but rather the patentee has not claimed precisely how to tune a liner to dampen both bending and shell mode vibrations.’ Judge Moore is exactly correct.”

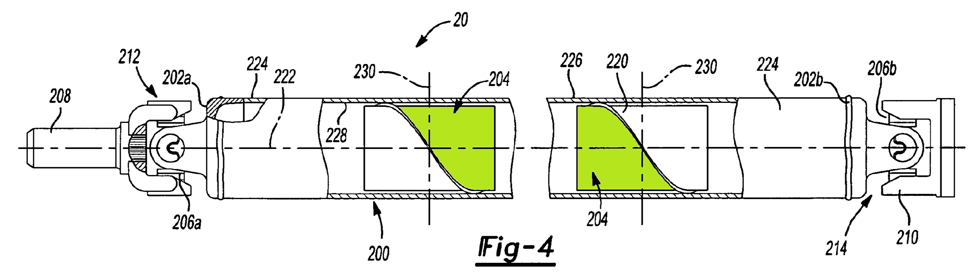

As I write this, the United States Supreme Court is deciding whether to grant certiorari in the American Axle case, setting the stage for another sea change in patent eligibility law. In 2020, the Federal Circuit issued a puzzling opinion penned by Judge Dyk finding American Axle’s method of manufacturing drive shaft assemblies (U.S. Pat. No. 7,774,911) to be a patent in-eligible law of nature. Specifically, claim 22 of the ‘911 patent recites “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner” and inserting the liner into a drive shaft such that it damps certain vibrational modes. Fig. 4 shows the liner (204) at the center of the dispute in green.

As I write this, the United States Supreme Court is deciding whether to grant certiorari in the American Axle case, setting the stage for another sea change in patent eligibility law. In 2020, the Federal Circuit issued a puzzling opinion penned by Judge Dyk finding American Axle’s method of manufacturing drive shaft assemblies (U.S. Pat. No. 7,774,911) to be a patent in-eligible law of nature. Specifically, claim 22 of the ‘911 patent recites “tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner” and inserting the liner into a drive shaft such that it damps certain vibrational modes. Fig. 4 shows the liner (204) at the center of the dispute in green.

“22. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising:

providing a hollow shaft member;

tuning a mass and a stiffness of at least one liner, and

inserting the at least one liner into the shaft member;

wherein the at least one liner is a tuned resistive absorber for attenuating shell mode vibrations and wherein the at least one liner is a tuned reactive absorber for attenuating bending mode vibrations.”

According to the Federal Circuit, claim 22 is “directed to a natural law because it clearly invokes a natural law, and nothing more, to accomplish a desired result”. Thus, claim 22 was held invalid.

In its petition for certiorari, American Axle argued that the “Federal Circuit has pushed Section 101 well beyond its gatekeeping function,” comparing its case to Diamond v. Diehr’s holding that an industrial process for rubber curing is patent eligible despite the claims “reciting and making direct use of the Arrhenius equation.” American Axle calls on the Court to clarify “what it means for a claim to be ‘directed to’ an ineligible concept in step one of the Alice test.”

Impossibly Vague

Since the Alice test was first promulgated by the Supreme Court in 2014, it has been a continuing source of confusion over how to apply the test’s vague directives. In Alice Step One, the question is whether the claim is “directed to” one of the judicial exceptions to patent eligibility, namely, a law of nature, natural phenomenon, or an abstract idea. If the answer to Alice Step One is “yes, the claim is directed to a judicial exception”, then the analysis proceeds to Alice Step Two to determine whether the claim is nonetheless patent eligible. The question in Step Two is whether any other elements of the claim transform the judicial exception into a patent eligible application. This step was referred to by the Court as a “search for an inventive concept”.

In American Axle, the Federal Circuit found that a claim to a manufacturing process is “directed to” a law of nature (Hooke’s Law) merely because it invokes a law of nature, without due regard to the other elements of the claim. This kind of judicial acrobatics has been a recurring problem since the Court first issued the Alice opinion because there is no established method for determining what it means to be “directed to” a judicial exception. In some cases, a claim is directed to a judicial exception simply because it invokes a law of nature. In other cases, the courts have looked to the “focus of the claimed advance over the prior art”. The United States Patent and Trademark Office itself, in trying to make sense of law, has issued guidance memoranda to the examining corps that sets forth a litany of fact-specific applications of the test, which it has had to revise periodically as new decisions are rendered. A litany is necessary because the Alice test does not admit of a concise general definition. It is impossibly vague.

Sidestepping the Real Problem

Ironically, all the Federal Circuit’s talk in American Axle of whether the claims are “directed to” a law of nature distracts from a more disturbing problem. Judge Moore’s dissent poignantly identifies that “[t]he majority’s true concern with these claims is not that they are directed to Hooke’s Law…, but rather the patentee has not claimed precisely how to tune a liner to dampen both bending and shell mode vibrations.” Judge Moore is exactly correct. This is not a Section 101 patent eligibility problem. This is a Section 112 problem. Either the specification (112(a)) or the claims (112(b)) are lacking in detail. Section 112 requires that the specification teach the person of ordinary skill in the art how to make and use the invention, and that the claims clearly set forth the metes and bounds of the property right. The Federal Circuit took issue with the claimed act of tuning, suggesting that the patentee improperly omitted necessary description of the tuning step in the claims. This, of course, is a requirement of the specification rather than the claims. Looking to the specification, we can see that the patentee explains what it means to tune a liner in terms of its effect but does not specifically state steps illustrating how to do so. The next logical question is whether it is necessary to specifically state steps to tune a liner, or can that be left to the skill in the art? If the steps are necessary, then the claim is invalid under Section 112(a) for lack of enabling disclosure in the specification. This is the question that the court should have asked. It can be answered without resorting to novel theories of Section 101 patent eligibility. Turning this into a patent eligibility question is wholly inappropriate, unnecessary, and further muddies already murky waters.

The Court Must Fix This

Until American Axle, the patent eligibility problem has been largely confined to biotech and software cases. Many practitioners presumed that claims to tangible products and their manufacture were safe. How could a tangible thing be a law of nature or an abstract idea? When courts can find that a method of manufacturing is nothing more than a law of nature, patent law has ceased to serve its Constitutional mandate to promote science and the useful arts. The Federal Circuit’s American Axle decision is a stark illustration of how broken and unworkable patent eligibility law has become. We hope that the U.S. Supreme Court takes this opportunity to breathe life and meaning into the Alice test.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Image ID:6628628

Copyright:lisafx

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

34 comments so far.

MaxDrei

June 21, 2021 05:05 pmCry? Surely not. AAA, just so you know, the patent owner’s process and my erstwhile client’s processes both remain trade secrets. Don’t make the mistake of supposing that the specification of the competitor’s parameter claim patent reveals their own process details. The point of their patent is to get to issue a claim that reads on to the products of the competitors.

But when opposition blows away those spurious claims, all the costs of getting and defending those claims are wasted. Filing and prosecuting all those oppositions is also costly, but hey, that’s these days just one of the costs of “doing business” I suppose. Nice work for patent attorneys, if they can get it.

But I’m a charitable individual. You may well be right, that the named inventors truly believed that they had made an inventive contribution to the art. It’s just that something got lost along the way, between writing the Invention Disclosure Statement, and the duly issued claim. You surely know that age-old sequence of cartoons that begins with a swing under a tree branch and the legend “What the inventor invented” all the way through to some absurd and non-functional combination of ropes and motor tyres depicting “What the issued claim recites”.

Anon

June 21, 2021 11:51 amMaxDrei,

You keep on SAYING “spurious,” but you ONLY have your emotions to back that up.

That just does not make it.

AAA JJ

June 21, 2021 11:15 amYour “those magic setting steps, that got the patent application to issue, are spurious” are the patentees “hey, we think we invented something, let’s file a patent application.”

Your insistence that the patentee is acting in bad faith is complete speculation on your part.

They filed. Your client didn’t. They ran the risk of keeping their process a trade secret. It blew up in their face. TFB.

Cry more.

Sheesh.

MaxDrei

June 21, 2021 10:20 amWell yes, of course the process is exhaustively documented, but if the claim recites various parameter ratios and steps of actively selecting parameters to satisfy those several ratios, the documentation won’t run to that, because those magic setting steps, that got the patent application to issue, are spurious. But nevertheless, the client uses a starting material that the claim reads on to and the client makes a product with the mechanical properties that the claim specifies so the patent owner can invite a court to draw the inference that we must be using their precious process.

And yes, indeed, on obviousness? There are of course countless ways to do it wrong. Ex post facto, with impermissible hindsight, is the most egregious though.

Anon

June 21, 2021 09:16 amMore of that “mind unwilling to learn” from you, MaxDrei.

These comments are NOT compliments.

You are NOT “saver” standing at the edge of the field of rye.

It is NOT “higher criticism” that you engender. You really seem clueless that your posts denigrate that which you seem to want to ‘promote.’

AAA JJ

June 21, 2021 08:22 amIf you have a trade secret it should be well documented. The steps. The characteristics/properties of the material used in the process. The characteristics/properties of the product of the process. If you can’t make a reasonable determination if you’re infringing the claim from that information then maybe you need to do some more analysis of this “trade secret.”

As for the “strong presumption of validity” that concerns you, in an IPR the presumption isn’t that strong. Especially when you consider that all of the APJ’s have super powerful hindsight goggles that make every 3, 4, 5+ combination of references look really convincing.

MaxDrei

June 21, 2021 07:42 amSo, my posts are “highly suspect”, are they? Super! I want them to raise suspicions, for that alone might prompt further enquiry, thoughtful reflection, and higher quality criticism in future.

The criticism I value most is from patent attorneys who counsel manufacturers on their patent interests in both the USA and Europe. For that though, I need to get active on blogs other than this one.

Anon

June 20, 2021 08:24 pmMaxDrie,

If you now want to assert that you succeed on the obviousness aspect, you can no longer claim a lack of prior art.

Overall, your posts on this topic are highly suspect, filled with emotion rather than substance and quite frankly, simply not believable.

Your “impede” is nothing but bluster.

MaxDrei

June 20, 2021 03:54 pmYou ask, how does one prevail at opposition proceedings at the EPO. You are quite right: neither good looks nor charming delivery will do the trick.

The answer is: usually with the obviousness provision of the EPC. That’s the difference between disputed proceedings at the EPO and cases such as American Axle, or Apple vs Yu in the US courts, in which the claims are knocked out 101-style for failure to get to the benchmark eligibility standard. As Gene observes in his newest posting, which has just appeared, this is pure Alice in Wonderland dysfunctionality in patent litigation. Presumably, you agree with Gene.

You seem to think that there is no cost, no harm, no victim, when these spurious parameter claims slip through to issue, and then are asserted. As I said, from where you’re standing, you would see it that way. But for manufacturers, and those who are asked for clearance opinions, the victim is the progress of useful arts.

Good patents ought to be swiftly enforced but bad patents impede technical progress and so need to be, just as swiftly, extinguished. Every commentator on the Axle case laments the ineligibility finding, observing that the claims would likely not survive obviousness attacks. I agree.

Curious

June 20, 2021 09:35 amWhat I mean is that the tricks that can get through to issue a method of manufacture claim don’t work with claims to products, so in the end all they can get to issue are the claims to the “method” of making the shaft.

Not familiar with manufacturing, are you? When it comes to “old” products (e.g., shafts) much of the innovation comes in the manufacturing. Being able to make the same thing but quicker, cheaper, better, etc. can make a huge difference.

Do they work in the USA when the defence relies on the output of a production plant in, say, China? Or, for that matter, somewhere in Europe? Or is it a prerequisite that the prior use of the method was within the USA?

What are you worrying about US patents for products made in China or Europe? Just don’t ship them to the US and you are good.

My client holds to the maxim that “Cheats don’t prosper” and , in Europe, at opposition proceedings at the EPO, that maxim usually holds true

Did they still the intellectual property? If they didn’t, then they weren’t cheating. Also, if prior existence of these parameters are so hard to prove because “there is no record whatsoever of our having adhered to them in our production process,” how does one prevail at opposition proceedings at the EPO? It certainly isn’t because of your good lucks and charm.

Oppose at the EPO and blow the cr3p patent away, for example.

See above. How does one successfully oppose without evidence of prior art?

the view in Europe is [blah, blah, blah]

You’ve been pumping your Europe is great spiel for how long on patent blogs? 15 years? Longer? It really gets tiresome.

The oppositions succeed and the flow of cr3p parameter applications seems to have dwindled. All a bit embarrassing for the owner of those spurious claims.

Seems to have dwindled? That is pretty wishy-washy statement if I ever heard of one.

I’m no longer serving this client

I wonder why. My guess is that patent prosecution is a lot cheaper than opposition proceedings, and opposition proceedings could have been avoided if there was better publication documentation of so-called spurious parameters.

MaxDrei

June 20, 2021 06:08 amWhat do I mean, when I point out that Axle failed to claim their driveshaft, as such? What I mean is that the tricks that can get through to issue a method of manufacture claim don’t work with claims to products, so in the end all they can get to issue are the claims to the “method” of making the shaft.

Yes, of course prior user defences are available, but (as every patent attorney knows) they are limited. You tell me, Curious, if you’re such a fan of them: Do they work in the USA when the defence relies on the output of a production plant in, say, China? Or, for that matter, somewhere in Europe? Or is it a prerequisite that the prior use of the method was within the USA?

Why doesn’t my client write spurious parameter patent applications? My client holds to the maxim that “Cheats don’t prosper” and , in Europe, at opposition proceedings at the EPO, that maxim usually holds true. Besides, the client has a reputation with its customers to protect. As far as I know, it remains market leader, its products delivering the highest quality.

You say that the spurious parameter patents put my client at a severe disadvantage. Well, you would, wouldn’t you, with your investment in patent applications to nurture. Manufacturers have a different viewpoint, however.

The best we’ve done is to whine and whinge, you venture? No, actually, quite a bit more than that. Oppose at the EPO and blow the cr3p patent away, for example. Much more satisfying, but it does require vigilance and hard work. Mind you, the view in Europe is that if you don’t look after your own interests, don’t expect anybody else to do it for you. The same in the USA, right?

I’m no longer serving this client so I don’t need to worry any longer about malpractice suits, thank you. But their strategy seems to be working. The oppositions succeed and the flow of cr3p parameter applications seems to have dwindled. All a bit embarrassing for the owner of those spurious claims.

Let’s see how embarrassing it all turns out to be, for the owners of the Axle patent.

Curious

June 19, 2021 09:14 pmFor many years I have acted for a client, let’s call it USALCO, that makes coiled strip for sale to industrial end users.

Do they have malpractice in Europe? It seems to me that you’ve been doing your client a great disservice.

Because these ratios are spurious, there is no record whatsoever of our having adhered to them in our production process. Needless to say, nowhere to be found elsewhere in the prior art is any teaching to pay attention to these ratios. Proving the claim to be invalid is, I repeat, not an easy proposition. Nevertheless, the claim reads on to most every competing product.

Instead of being proactive and patenting and/or at least disclosing some of these so-called “spurious” parameters, you are letting your client’s competitor beat your client to the punch. This has put your client at a severe disadvantage vis-à-vis their competitor. You’ve known about this for years, and the best you’ve done is complain about “spurious” parameters on some patent blog?

Are you saying that the way to defeat the spurious patent being asserted is to disclose my complete process details to my competitor?

You don’t have to disclose the “complete” process — but you certainly need to being doing more than what you have been doing.

Why didn’t Axle claim their driveshaft as such? If the USPTO is anything like the EPO, it is very often possible to drive a method claim through to issue where the product claim is untenable.

What do you mean? American Axle claimed a method.

BTW, are you aware of the prior use defense in 35 USC 273?

MaxDrei

June 19, 2021 05:40 pmAAA, thanks. I have a complete record of what I am doing. What I do NOT have a record of is what I am NOT doing, namely selecting the parameters of my process in accordance with the spurious teachings of this spurious patent.

The patent instructs to select various numerical values in accordance with various stated ratios, and I have “no record” that I did this when setting up my production process. Nevertheless, says the patent owner, you must have done, see, because your product has the same composition as in the claim and the same good performance attributes promised by the patent. Therefore, prima facie, it must have been made with the patented method.

Are you saying that the way to defeat the spurious patent being asserted is to disclose my complete process details to my competitor?

Why didn’t Axle claim their driveshaft as such? If the USPTO is anything like the EPO, it is very often possible to drive a method claim through to issue where the product claim is untenable. One reason is because the Examiners can find art to demonstrate that the claimed product is old but finding evidence that the claimed method of making it is old is a lot more challenging.

AAA JJ

June 19, 2021 04:58 pmHow is your process a trade secret if you have no record(s) of what you’re actually doing?

Anon

June 19, 2021 02:58 pmMaxDrei,

You are the poster child of a person with a mind unwilling to learn.

MaxDrei

June 19, 2021 08:16 amThanks for all the reactions. In reply the following further comments will, I hope, provide further food for reflection.

For many years I have acted for a client, let’s call it USALCO, that makes coiled strip for sale to industrial end users. I have a competitor (GERAL). Their strip is inferior because my production process (a trade secret) delivers superior results. Nevertheless GERAL writes patent applications full of spurious parameters that bamboozle the Patent Office, go to issue, and read on to my product. A typical claim includes number ranges of ratios of alloying element contents, casting process steps, rolling pass thickness reductions, and ratios of physical, chemical and electrical properties of the finished product at different temperatures. Because these ratios are spurious, there is no record whatsoever of our having adhered to them in our production process. Needless to say, nowhere to be found elsewhere in the prior art is any teaching to pay attention to these ratios. Proving the claim to be invalid is, I repeat, not an easy proposition. Nevertheless, the claim reads on to most every competing product.

Now you may say that USALCO enjoys a right of continued use of their old process. That may be, but that right does not cover improvements in the old process, which we are making all the time, with the spurious claim inevitably still reading on to the improved product.

Tell me, what are your personal experiences, as a manufacturer, of being confronted with a mischievous, spurious, clever parameter method claim?

Curious

June 18, 2021 03:15 pmSo, the parameters here are classic spurious ones. They purport to be an inventive selection but in fact amount to a claim covering everything that “works”. In a nutshell, there’s the mischief, with this sort of scrivening.

Since you are clueless about the technology, any assertion by you that these are “spurious” parameters is pure speculation on your part.

There are patents involving the tuning of shafts that go back 100 years. If these parameters were something that were known in the art, one would think that they would have been described somewhere in some kind of literature. In the absence of this evidence — you are doing what you’ve been doing for over a decade now (in this forum and elsewhere) which is speaking out of an orifice intended for other things aside from speaking.

I avoid being crass with my interactions with others on such a public forum. However, I do make exceptions for a rare few, like yourself, who have made it abundantly clear that they are not deserving of being treated with basic civility. Trust me, your place on that list is well-deserved.

B

June 18, 2021 02:44 pmMaxDrei “So, the parameters here are classic spurious ones.”

I believe that the 2% threshold is to eliminate de minimus changes of vibrations that an examiner might assert as an improvement due to almost anything, such as stuffing a driveshaft with paper.

This is a valid approach.

“They purport to be an inventive selection but in fact amount to a claim covering everything that “works”. In a nutshell, there’s the mischief, with this sort of scrivening.”

Which, if true, leads to an easy 102 or 103 rejection, right?

“For a PTO Examiner armed with only the resources the PTO makes available, it’s hard, even impossible to prove with evidence that the combination of numerical ranges is indeed part of the prior art methods.”

Which is why defendants are allowed to present evidence while observing that it’s easier in theory to prove something is known as opposed to whether that something is well-known, routine, and conventional.

Of course, post-Alice most of the CAFC judges don’t count to 102 or 103. I mean, why bother when you can wipe a case off the docket with spurious assertions and meaningless platitudes?

AAA JJ

June 18, 2021 02:08 pm“The classic way to bamboozle the PTO into issuing a claim is to stack that claim with several parameters and argue that the art fails to disclose that combination of numerical ranges.

Here, Applicant’s position is that there is nothing new in tuning, as such, or tuned driveshafts, as such. See, it doesn’t even claim the shaft as such. It is the particular method of tuning as claimed, which Applicant has as being new and inventive. The parameters you cite are there to establish the alleged non-obviousness of that claimed method.

But tuning by its very nature involves matching vibration frequencies. And if the “tuning” fails to attenuate vibration by 2% then it isn’t tuning at all.

So, the parameters here are classic spurious ones. They purport to be an inventive selection but in fact amount to a claim covering everything that “works”. In a nutshell, there’s the mischief, with this sort of scrivening.

For a PTO Examiner armed with only the resources the PTO makes available, it’s hard, even impossible to prove with evidence that the combination of numerical ranges is indeed part of the prior art methods.

So the claim issues, with a strong presumption of validity, even though, for the skilled and experienced driveshaft designer, it is laughably lacking in anything new or inventive.”

This is the classic, “It’s so old and well known that nobody ever bothered to write it down!!!!” argument.

Not buying it.

Anon

June 18, 2021 07:21 amMaxDrie,

You continue to be rude here.

You have not answered Curious’s question with any substance, but instead merely reiterated your feelings.

If indeed “laughable” or “spurious,” then submit the evidence that makes it so.

Otherwise, kindly STFU.

(Also, that you seem to espouse “shortcuts” in law, yet assert that you practice in law for decades, shows an alarming lack of ethical appreciation of how law must be constrained in that Ends cannot justify the means)

MaxDrei

June 18, 2021 04:24 amDear Curious (by the way, I do like your name and hope that it is a true reflection of your personality), The USPTO is there to issue patents unless the claims embrace something that is old, obvious or offends some other provision of the statute. Just because the PTO issues a claim does not prove it to be valid.

The classic way to bamboozle the PTO into issuing a claim is to stack that claim with several parameters and argue that the art fails to disclose that combination of numerical ranges.

Here, Applicant’s position is that there is nothing new in tuning, as such, or tuned driveshafts, as such. See, it doesn’t even claim the shaft as such. It is the particular method of tuning as claimed, which Applicant has as being new and inventive. The parameters you cite are there to establish the alleged non-obviousness of that claimed method.

But tuning by its very nature involves matching vibration frequencies. And if the “tuning” fails to attenuate vibration by 2% then it isn’t tuning at all.

So, the parameters here are classic spurious ones. They purport to be an inventive selection but in fact amount to a claim covering everything that “works”. In a nutshell, there’s the mischief, with this sort of scrivening.

For a PTO Examiner armed with only the resources the PTO makes available, it’s hard, even impossible to prove with evidence that the combination of numerical ranges is indeed part of the prior art methods.

So the claim issues, with a strong presumption of validity, even though, for the skilled and experienced driveshaft designer, it is laughably lacking in anything new or inventive.

It seems to me that judges are using 101 as a judicial shortcut, whenever they see a claim that is a clear FAIL on the substantive provisions of patentability. The solution to that problem, the way to put them off taking that attractive shortcut, is childishly simple: higher quality patent drafting.

Curious

June 17, 2021 06:59 pmSorry though. I have no idea what parameters you allude to.

That doesn’t surprise me as you have a propensity to opine on things you know little about.

Claim 1 of USP 7774911 recites “such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about .+-.20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system.”

Parameter 1: “configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%.”

Parameter 2: “tuned to within about .+-.20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly.”

Dependent claims 2-4 and 7-11 also recite parameters.

Are you asserting that there is anything new (let alone not obvious) in such stipulations?

The claimed invention, AS A WHOLE, is both new and not obvious. This is what was determined by the USPTO and I’m not here to doubt the presumption of its validity. Also, as far as I am aware, no one has presented any evidence that it is not. Do you have evidence otherwise?

TR3

June 17, 2021 04:48 pmIPGuy: “Section 101 needs far more than a tune-up.”

No doubt. I would prefer a legislative fix. The Tillis-Coons bill would have been my preference, but this is the opportunity we have right now. At this point, I’ll take what I can get. All we are likely to see from a SCOTUS decision is a “tune-up”. Meanwhile, the CAFC has gone Through the Looking Glass.

Dominic Frisina

June 17, 2021 04:40 pmB: “An excellent article, BUT will the SCOTUS accept the AA case?”

Thank you. One can only hope.

Anon

June 17, 2021 04:24 pmMaxDrei,

Do you recognize that your own follow-up questions (“are you asserting… new (let alone not obvious)…”) actually make the point that this is NOT being decided correctly under our Sovereign’s eligibility law?

If you are seeking answers under a different section of law, what does that tell you?

ipguy,

I entirely agree,

ipguy

June 17, 2021 03:45 pm“Tune-Up”

I appreciate the motor vehicle analogy in the title but Section 101 jurisprudence needs far more than a judicial “tune-up” since “tune-up” implies something is working but just needs some minor adjustment to get it back to peak operation. Section 101 needs far more than a tune-up.

MaxDrei

June 17, 2021 02:20 pmCurious, you say:

“What was disclosed in American Axle was certain parameters to which the shafts should be tuned”

as if this settles the issue.

Sorry though. I have no idea what parameters you allude to.

Perhaps the stipulation that the “tuning” must attenuate vibration by an amount of at least 2% (or some other Catch-all charade of a “limiting” range)?

Or perhaps the stipulation that to “tune” the shaft one is to vary the “mass” and/or the “stiffness” of a shaft component.

Are you asserting that there is anything new (let alone not obvious) in such stipulations?

B

June 17, 2021 01:11 pm“As I write this, the United States Supreme Court is deciding whether to grant certiorari in the American Axle case, setting the stage for another sea change in patent eligibility law.”

An excellent article, BUT will the SCOTUS accept the AA case?

My ONE criticism. “Impossibly vague” doesn’t quite describe how bad the CAFC’s jurisprudence is on the issue.

Curious

June 17, 2021 12:13 pmMany practitioners presumed that claims to tangible products and their manufacture were safe.

Only those practitioners that weren’t reading the case law but instead were just looking at case notes. The law being “developed” at the Federal Circuit wasn’t going to limit itself to just “biotech and software cases.” Just look at Yu v. Apple.

The Federal Circuit took issue with the claimed act of tuning, suggesting that the patentee improperly omitted necessary description of the tuning step in the claims. This, of course, is a requirement of the specification rather than the claims. Looking to the specification, we can see that the patentee explains what it means to tune a liner in terms of its effect but does not specifically state steps illustrating how to do so. The next logical question is whether it is necessary to specifically state steps to tune a liner, or can that be left to the skill in the art? If the steps are necessary, then the claim is invalid under Section 112(a) for lack of enabling disclosure in the specification. This is the question that the court should have asked.

The first statement is accurate — and is a point I’ve made time and time again. The claims aren’t intended to describe/explain/enable the invention. That’s NOT their purpose. Rather, the claims distinguish the invention over the prior art.

As for the tuning aspect, which is another thing I’ve opined on before, the tuning of shafts has been done for well over a century. What was disclosed in American Axle was certain parameters to which the shafts should be tuned — how they are tuned to arrive at those parameters is well within the knowledge of those skilled in the art.

MaxDrei

June 17, 2021 07:23 amWhich is the better vehicle for SCOTUS to drive through a clarification of 101 law? As I see it, the difference between the two cases is that Yu has loads of detail in the specification whereas Axle has none.

Consider axle’s parallel case at the EPO. There, Applicant informs the EPO that there is no need for the specification to provide any teaching on how to “tune” a driveshaft because for the skilled person that is well-known, conventional and routine. The invention is the flash of recognition that, with just one cardboard liner, you can tune out two or more modes of vibration. How you do it is up to you.

For me, Axle is a super case for the Supreme Court, if only because its subject matter is something they can relate to (and not burdened by the sheer incomprehensibility of inventions in, say, AI and DNA).

Anon

June 17, 2021 06:49 amWell Anonymous, you alight upon one of the two shears that make up the Kavanaugh Scissors – were those two to be joined (possibly with ACB as a pivot), the Gordian Knot could be cut by the Court itself.

But I do think that you may be correct in that it will take Congress waking up to realize another Branch has usurped its power to finally put an end to the mischief. This path has been put on the table as well, as I have well noted that Congress has within its Constitutional power to employ jurisdiction stripping of items of non-original jurisdiction from the Supreme Court (and to comply with Marbury, and to clean up the indoctrinated mess at the CAFC), couple with a reformulation of an Article III body NOT subject to brow beating from the Supreme Court.

Anonymous

June 17, 2021 01:00 amBreathe life and meaning into Alice? No. Congress needs to end the mess immediately. Only Congress.

Yu v. Apple is a good candidate for cert, showing that the judiciary has no constitutional authority to conjure its own exceptions to statute. The mess we’re in is the exact reason why judges shouldn’t legislate.

Question presented: May the court skip the statutory definition of patent eligibility under 35 USC 101 and instead apply only the court’s patent eligibility standard involving “judicial exceptions,” or, in the mutually exclusive alternative, is it true that the Supreme Court “may not engraft its own exceptions onto the statutory text,” per Henry Schein, Inc. v. Archer & White, Inc., 139 S.Ct. 524 (2019)?

Pro Say

June 16, 2021 10:03 pmCrikey! Next thing you know the CAFC will invalidate . . . oh, I don’t know . . . camera patents!

Nah. Just kidding. That would never happen.

Right?

Concerned

June 16, 2021 05:47 pmFrankly the USPTO and courts do whatever they want. Solve this problem, other reasons will be given to reject.

My application has no 102, 103 or 112 issues. USPTO and PTAB say it solved a long term problem and met the 101 as written by Congress, however, PTAB alleges the application does not meet their (undefined) judical definition.

USPTO and PTAB argue well understood, routine and conventional, yet cannot provide one example where the inventive concept is used in any commerce or my commerce.

A person does not need to be an attorney to realize 102 and 103 are put in code for a reason and that reason is not to reject everything under 101.

The whole patent system should be abolished. At least an inventor will know there is no official patent system instead of being led to believe there is a legitimate one.