“The question [in American Axle] begged by Judge Dyk’s requirement of enablement by the claims as written, and Judge Chen’s invalidation of claims that offer ‘nothing more’ than invocation of a law of nature, is why any of this matters when deciding whether claimed subject matter is a ‘process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or new and useful improvement thereof.’”

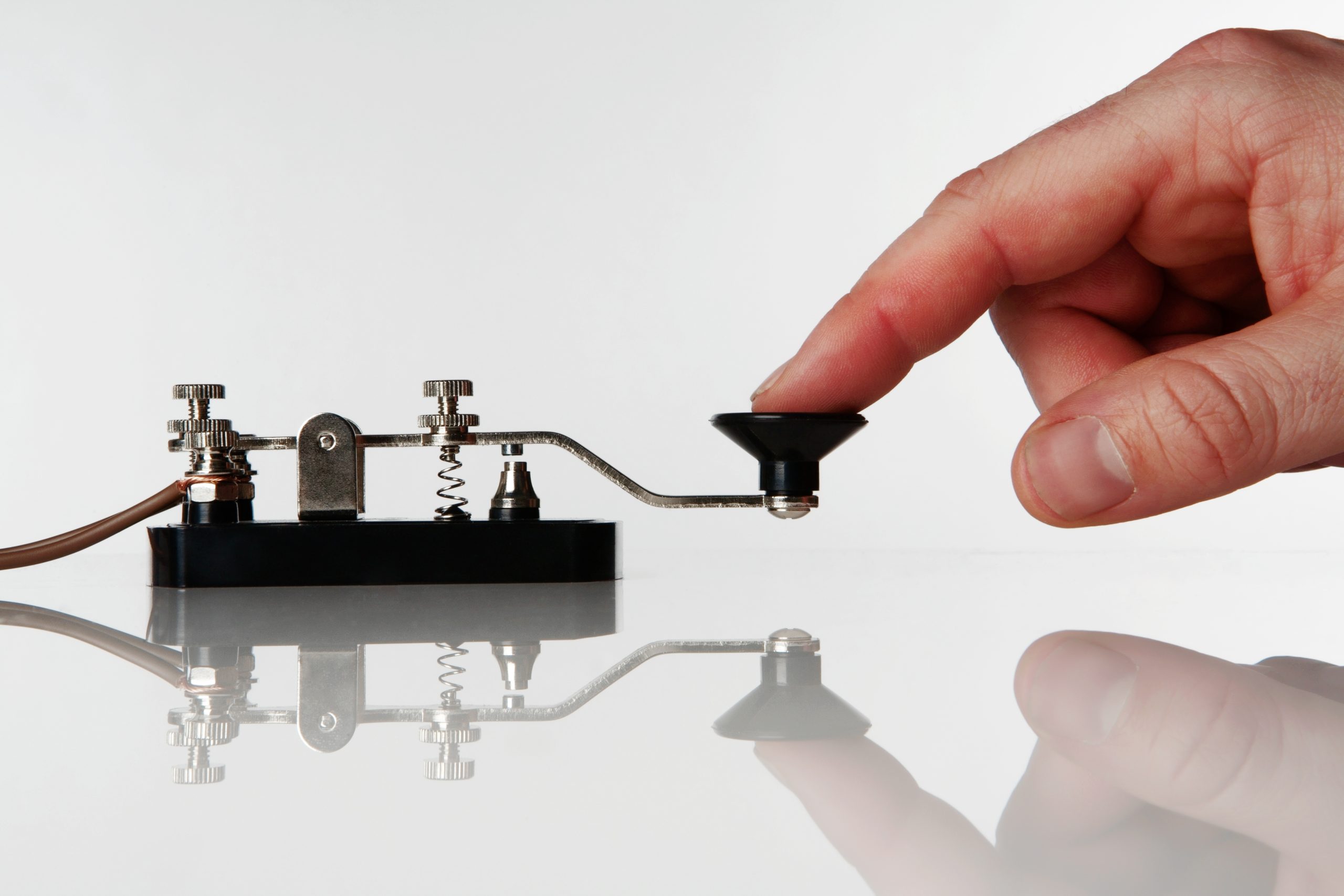

It may seem surprising that the patent eligibility of making an axle for a motor vehicle could be so divisive among judges of a court tasked by design with the most difficult questions of patent law. And this internal division might appear particularly surprising given that the roots of the views expressed among the judges in the split decision by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in American Axle & Mfg., Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC et al., Case No. 2018-1763, slip op. (Fed. Cir., July 31, 2020) pre-date a famous 170-year old Supreme Court decision involving Samuel F. B. Morse’s telegraphy method, which was featured by the concurring opinions in the denial of the petition to rehear the case en banc. When viewed in a larger context, however, the most significant realization might be a unifying and constructive underlying message from the Federal Circuit bench.

It may seem surprising that the patent eligibility of making an axle for a motor vehicle could be so divisive among judges of a court tasked by design with the most difficult questions of patent law. And this internal division might appear particularly surprising given that the roots of the views expressed among the judges in the split decision by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in American Axle & Mfg., Inc. v. Neapco Holdings LLC et al., Case No. 2018-1763, slip op. (Fed. Cir., July 31, 2020) pre-date a famous 170-year old Supreme Court decision involving Samuel F. B. Morse’s telegraphy method, which was featured by the concurring opinions in the denial of the petition to rehear the case en banc. When viewed in a larger context, however, the most significant realization might be a unifying and constructive underlying message from the Federal Circuit bench.

Why O’Reilly v. Morse?

The facts and history of the case are straightforward. A patent owned by American Axle Manufacturing, Inc. (AAM), U.S. Patent No. 7,774,911 (“the ‘911 patent”), was asserted against Neapco Holdings LLC and Neapco Drivelines LLC (“Neapco”). Independent claims 1 and 22 of the ‘911 patent were directed to “a method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system” for a motor vehicle, and both claims were held by the district court to be invalid as claiming subject matter ineligible for patent protection under 35 U.S.C. § 101. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the decision of the district court. A petition to rehear the case en banc was denied with an evenly divided court, and the earlier opinion of the Federal Circuit was modified, remanding claim 1 to the district court and reaffirming the ineligibility of claim 22.

Significantly, a famous case that was given only cursory mention in the first opinion issued by the Federal Circuit, O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. (15 How.) 62 (1853), became pivotal in the concurring opinions of the denial of rehearing en banc and in the modified opinion. Judge Dyk in his concurring opinion to the denial stated that the method of claim 22 of the ‘911 patent was ineligible for patent protection because it “contains no further identification of specific means for achieving …[reduced vibrations in a shaft assembly]…, but merely invokes the natural law that defines the relation between stiffness, mass, and vibration frequency….” Like the eighth claim at issue in O’Reilly v. Morse, which limited an exclusive right to “printing intelligible characters…at any distances” only to use of electromagnetism, Judge Dyk found that the “omission of needed specifics in the claim was the problem, not a reason to find eligibility.”

In a separate concurring opinion, Judge Chen also compared claim 22 of the ‘911 patent to Morse’s eighth claim, but did so by stating that both claims call for “nothing more” than the use of a natural law. Two distinctions were made by Judge Chen between the first and eighth claims of Morse, and claims 1 and 22 of the ‘911 patent. The first was a limitation in the first claim of Morse’s patent to means “substantially as set forth in the foregoing description of the first principal part of my invention.” The eighth claim, by way of contrast, lacked this limitation. The second distinction raised by Judge Chen was “tuning” in claim 22 of mass and stiffness of a liner to be incorporated into the shaft assembly constructed by the method of the invention. According to Judge Chen, varying mass and stiffness necessarily invoked Hooke’s law as limitation of the claimed method, just as if that law of nature had been explicitly called out. Claim 1 of the ‘911 patent, by way of contrast, did not recite either mass or stiffness and, therefore, “cannot properly be read to expressly invoke the Hook’s law relationship between mass, stiffness, and frequency.” For Judge Chen, “[i]f claim 22 had omitted any reference to mass and stiffness, such that the claim simply recited ‘tuning to match the relevant frequency or frequencies,’ there would be no basis to say that the claim invokes Hooke’s law.”

Judge Chen found that narrowing the subject matter of the eighth claim of Morse to the embodiments of the specification saved the first claim, despite the fact that both claims recited magnetism, or electromagnetism, as the motive force. He also held that removal of reference to variables of a law of nature could save a claim if, by doing so, the claim was no longer limited to any particular law of nature. In essence, the parallel drawn between O’Reilly v. Morse and AAM v. Neapco by Judge Chen, of deliberate confinement to the specification on one hand, and removal of reference to laws of nature, naturally-occurring phenomena, and abstract ideas (where there is an alternative) on the other, put these cases on two sides of the same coin of patent eligibility, and so O’Reilly v. Morse was instructive precedent.

The Greater Question

The question begged by Judge Dyk’s requirement of enablement by the claims as written, and Judge Chen’s invalidation of claims that offer “nothing more” than invocation of a law of nature, is why any of this matters when deciding whether claimed subject matter is a “process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or new and useful improvement thereof.” This is a classic case of failure to recognize that the Emperor is lacking clothes. For Judge Dyk, “a contrary result would deny a true inventor (an inventor who determined a specific means to achieve the claimed result) the fruits of his or her invention.” This presumption was also asserted in O’Reilly v. Morse, and is likely the reason this case has endured, despite all the changes that have taken place in patent law since it was decided in 1853. The Court there said that granting an “exclusive right to every improvement where the motive power is the electric or galvanic current, and the result is the marking or printing intelligible characters, signs, or letters at a distance” effectively “shuts the door against inventions of other persons, [while] the patentee would be able to avail himself of new discoveries in the properties and powers of electro-magnetism which scientific men might bring to light.” In both Judge Dyk’s reasoning and that of the majority in O’Reilly v. Morse, a patentee thereby secures “every new discovery and development of the science,” for which “the public must apply to him,” including any “manner or process which he has not described and indeed had not invented, and therefore could not describe when he obtained his patent.” The Court in O’Reilly v. Morse specifically called out such a claim as “too broad, and not warranted by law.”

At the time O’Reilly v. Morse was decided, just as today, patent protection was not limited to improvements that were free of the scope of the exclusive rights of prior or subsequent inventors. As stated by Justice Story in 1813 (Woodcock v. Parker, 30 F. Cas. 491 (C.C.D. Mass. 1813) (No. 17,971), a “subsequent inventor cannot, by obtaining a patent therefore, oust the first inventor of his right, or maintain an action against him for the use of his own invention.” This logic extends to embodiments of claimed inventions based on later-developed technology; a chair held together by a later-developed and improved glue will still infringe a claim that reads on the chair, even if that chair, as improved by the later-developed glue, is itself patentable. Likewise, the inventor of the earlier-claimed chair would infringe the claim of the subsequent patentee if he employed the improved glue. If the majority in O’Reilly v. Morse was not proscribing claims to subject matter that would be infringed by the practice of subject matter subsequently invented, then the exclusive rights expressed by that Court must be limited to claimed inventions as disclosed in the patent, regardless of whether all embodiments of that disclosed subject matter were enabled at the time of the invention. To hold otherwise would fundamentally cripple essentially all patents by limiting them to technology available at the time of their filing.

This presents an apparent paradox because, while claims are readable on later-developed and even patentably-distinct embodiments, the scope of patent protection is limited to the invention of the subject matter claimed, and the specification must, by virtue of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) “contain a written description of the invention…as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains…to make and use the same.” This paradox is present in O’Reilly v. Morse and AAM v. Neapco in that the lack of limitation to the invention described in their respective specifications was the basis for distinguishing the eighth claim from the first claim in O’Reilly v. Morse, just as, conversely, preemptive invocation of a law of nature was the basis for distinguishing claim 22 from claim 1 of the ‘911 patent. This paradox is resolved by the presence of invention in all valid patent claims that are readable on improvements within their scope, and limitation of claimed subject matter to what has been “invented.” The presence of invention is, under current law, the fundamental concept separating subject matter that is eligible for patent protection from the judicial exceptions to patent eligibility of “laws of nature, naturally-occurring phenomena, and abstract ideas.”

Application of Principle as the Foundation for Patent Protection

The notion of “invention” as the limit to the scope of patent protection and the threshold for patentable distinction historically also have been viewed as two sides of a coin. Both have their origin in the nature of patentable subject matter relative to unpatentable laws of nature, naturally-occurring phenomena and abstract ideas. Assessment of patent eligibility against a background of ineligible “principles” was first and most famously expressed in the late eighteenth-century English cases of Boulton and Watt v. Bull (1795) and Hornblower and Mayberly v. Boulton and Watt (1799). In those cases, the Court of Common Pleas and the Court of the King’s bench, respectively, wrestled with the validity of patent protection for a new method of use of a known steam engine expressed in terms of “principles” under the Statute of Monopolies, which only provided for protection of “manufactures.” Ultimately it was decided that, while “principles” themselves were not subject to patent protection, their application could be. For the purpose of deciding patent eligibility, methods were equivalent to “manufactures” under the Statute of Monopolies, and the basis for this equivalency was that both were viewed as embodiments of principle. Stated another way, “mere principles” were not patentable until they are “embodied and reduced into practice,” but the mode of that application was less important than the presence of principle in whatever form the application took, and so principle became the link between manufactures and methods that allowed for grant of an exclusive right to a new use of a known device, and to a novel device that could be put to a beneficial use.

Far from constituting exceptions to eligibility for patent protection, new application of “principles,” namely laws of nature, naturally-occurring phenomena, and abstract ideas, were the foundation for patent protection and the basis for finding patentable distinction relative to known manufactures and their methods of use. The Patent Act of 1793 limited patent protection to “any person, who shall have discovered an improvement in the principle of a machine, or in the process of any composition of matter.” Conversely, and by the same Act, “simply changing the form or the proportions of any machine, or composition of matter, in any degree, shall not be deemed a discovery,” meaning that novelty, in and of itself, in the absence of any new application of principle, was insufficient, regardless of utility or importance. In short, a new and useful application of a law of nature, naturally occurring phenomenon, or abstract idea was the foundation for patentable “invention.”

In Part II of this article we will look more closely at the seemingly disparate opinions in AAM v. Neapco against this backdrop of historical approaches to eligibility. Ultimately, we will see that they bring us full circle to suggest a unifying message that—while perhaps troubling—can guide us going forward.

Further reading on AAM v. Neapco on IPWatchdog:

New Enablement-Like Requirements for 101 Eligibility: AAM v. Neapco Takes the Case Law Out of Context, and Too Far – Part I

AAM v. Neapco Misreads Federal Circuit Precedent to Create a New Section 101 Enablement-like Legal Requirement – Part II

The Re-Written American Axle Opinion Does Not Bring Peace of Mind for Section 101 Stakeholders

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

9 comments so far.

Anon

September 22, 2020 01:52 pm“brake on progress delivered by the restraint on trade caused by the issue of a bad (over-broad) patent.”

And what exactly is this thing that you refer to?

Is this the legendary Supreme Court “MAY impede?”

“One consequence of recent US case law on eligibility is that it will bring more businesspeople to a realisation of the value of top quality claim drafting, and thereby lead to higher patent drafting standards. And I’m not here alluding to mere scrivening.”

What you allude to is nothing more than a mirage – and you would know this had you paid any real attention to the mess created by the US Courts. High ranking members of each of the three branches of our government have panned the very US case law that you would seek to celebrate.

This post of yours, while sounding all ‘good and noble’ is nothing but dross. You want to talk about scrivining, look at your own contributions here.

TFCFM

September 22, 2020 10:07 amNSP: “In both Judge Dyk’s reasoning and that of the majority in O’Reilly v. Morse, a patentee thereby secures ‘every new discovery and development of the science,’ for which ‘the public must apply to him,’ including any ‘manner or process which he has not described and indeed had not invented, and therefore could not describe when he obtained his patent.’ ”

There is your answer. Patentees may not claim that which they have not invented, and claims which attempt to encompass all instrumentalities and methods which will achieve a desired result (without disclosing them) are ineligibly abstract — as well as being both not-possibly fully described and not-possibly fully enabled.

It isn’t that difficult to understand, as soon as one dispenses with the laughable proposition that including the word “process” (or “method”) or reciting at least one tangible item in a claim MaGiCkAliShLy transforms an abstract sentiment into a patent-eligible invention (and that this remains equally so even if the one has also described one or a few actual embodiments of the realized sentiment, be it a “tuned” axle or characters printed at a distance “using electromagnetism”).

Hopefully, the Federal Circuit (or the Supreme Court, if necessary) will express this truism in a form likely to defeat even the most double-talking, hand-waving-ish patent applicant and his/her advocates.

One can potentially patent what one invents — not what one merely wishes one had invented.

Anon

September 22, 2020 08:29 amMr. Morinville,

This op ed may resonate with you:

https://youtu.be/9bZl_0XczWg

(in a ‘bread and circus’ manner)

MaxDrei

September 22, 2020 08:11 amI read all this stuff about patents for underlying principles and for improvements, scratch my head and look forward to Part II, in which I hope to read how, for the next 20 years, the USA will balance i) the incentive patents deliver, to promote the progress, with ii) the brake on progress delivered by the restraint on trade caused by the issue of a bad (over-broad) patent.

Europe has had since 1978 a pan-European criterion of patentability, namely, that the scope of the claim must be “commensurate” with the “contribution” that the invention makes to the art in which it is located. Any claim with a scope wider than that is not valid. Any claim you draft which is narrower than that is short-changing the client. It can’t get any simpler or more equitable than that.

In consequence, the EPO routinely grants not only improvement patents but also patents on what one might term a “new principle”. Means plus function claim language at the point of novelty is routine, uncontroversial, albeit largely confined to those inventions that reach the level of a new principle.

I love drafting patents, that set out the contribution accurately and persuasively and thereby maximise the defensible scope of protection which my client shall, for the next 20 years, enjoy. For me, patent claim drafting is the apex of the skillset of a patent attorney, the highest expression of the talent and aptitude of a patent practitioner. One consequence of recent US case law on eligibility is that it will bring more businesspeople to a realisation of the value of top quality claim drafting, and thereby lead to higher patent drafting standards. And I’m not here alluding to mere scrivening. Substance is more important than form.

Part II? Bring it on.

concerned

September 21, 2020 09:19 pm@1: “However, what is particularly reprehensible is when judges simply make sh_t up to justify a decision.”

Also happens at the USPTO and/or a second examiner is sent in close the “rejection” deal.

Pro Say

September 21, 2020 08:01 pmYet more CAFC:

Hocus Pocus

Mumbo Jumbo

Voodoo

(pick one)

Paul Morinville

September 21, 2020 07:54 pmIt looks like the CAFC is implementing the 112f language that failed to pass congress last year into case law. This is a gross violation of the public trust.. Judges are not legislators. Legislation that failed to pass in Congress failed because the people did not want it to be law. Judges have no right to pass it anyway.

Water the tree of liberty

Anon

September 21, 2020 11:42 amThe asserted paradox is an illusion.

The vast majority of patents are improvement patents – that by their very nature improve upon a pre-existing item.

The very essence of ANY improvement patent would — according to the fallacy of the mirage — necessarily mean that the item being improved was improvidently granted.

ONLY a fully developed and not-possible-to-contain-any improvement patent would survive such a ‘philosophy,’ and you might as well simply not have a patent system at all.

Curious

September 21, 2020 11:33 amIn a separate concurring opinion, Judge Chen also compared claim 22 of the ‘911 patent to Morse’s eighth claim, but did so by stating that both claims call for “nothing more” than the use of a natural law.

It would have been comparable only if the claim recited something to the effect of “being the use of reducing vibration using Hooke’s law.” However, unlike the theory of electro-magnetism, which was just being developed in the mid-1800s, which was something,” the reduction of vibration (in propeller shafts) had been going on for at least a century, and any reduction in vibration necessarily involves Hooke’s law.

The second distinction raised by Judge Chen was “tuning” in claim 22 of mass and stiffness of a liner to be incorporated into the shaft assembly constructed by the method of the invention. According to Judge Chen, varying mass and stiffness necessarily invoked Hooke’s law as limitation of the claimed method, just as if that law of nature had been explicitly called out.

The (il)logic behind this observation is that laws of physics are necessarily involved in any invention that invokes physical structure. The Wright Brother’s inventive airplane necessarily invoked Newton’s Third Law. All airplanes invoke Newton’s Third Law — that does not make them unpatentable subject matter.

This is a classic situation where judges muck up the law (and the facts) in order to arrive at some pre-ordained decision. This is also how we got Benson from the Supreme Court, which was also wrong on the facts. Unfortunately, the Courts are able to get away with it because one needs a finer understanding of the technology to recognize how badly the Court screwed up the facts.

It is understandable that judges can disagree based upon philosophical differences. However, what is particularly reprehensible is when judges simply make sh_t up to justify a decision. Not only is the patent holder harmed (by having what should be patentable deemed unpatentable), the judiciary and the patent system itself is harmed as it calls into question the impartiality and both the legal/technical competence of the judiciary.