“A review of the disclosure and claims of the recently issued ‘819 patent and the now several years old ‘715 (Chargepoint) patent offer a valuable drafting lesson in this new age of eligibility uncertainty.”

While perusing the Patent Gazette looking for interesting, recently issued patents to discuss during Intro to Patent Prosecution, I stumbled across U.S. Patent No. 10,668,819, titled Enhanced wireless charging. Issued on June 2, 2020, this patent was filed on May 22, 2017. The reason this particular patent caught my attention as I was looking for software patents and other high-tech patents and claims I could dissect for students was because the invention is to a wireless vehicle charging station. Those familiar with the Federal Circuit’s decision in ChargePoint, Inc. v. SemaConnect, Inc., 920 F.3d 759 (Fed. Cir. 2019), will recall that Chief Judge Prost (joined by Judge Chen) ruled that the claims directed to a wireless vehicle charging station of U.S. Patent No. 8,138,715, were abstract and patent ineligible.

While perusing the Patent Gazette looking for interesting, recently issued patents to discuss during Intro to Patent Prosecution, I stumbled across U.S. Patent No. 10,668,819, titled Enhanced wireless charging. Issued on June 2, 2020, this patent was filed on May 22, 2017. The reason this particular patent caught my attention as I was looking for software patents and other high-tech patents and claims I could dissect for students was because the invention is to a wireless vehicle charging station. Those familiar with the Federal Circuit’s decision in ChargePoint, Inc. v. SemaConnect, Inc., 920 F.3d 759 (Fed. Cir. 2019), will recall that Chief Judge Prost (joined by Judge Chen) ruled that the claims directed to a wireless vehicle charging station of U.S. Patent No. 8,138,715, were abstract and patent ineligible.

It’s All in the Claim

In these types of cases one must be initially reminded of Judge Giles Sutherland Rich’s pithy truism: “[t]he name of the game is the claim.” Giles S. Rich, The Extent of the Protection and Interpretation of Claims-American Perspectives, 21 Int’l Rev. Indus. Prop. & Copyright L., 497, 499 (1990). Perhaps more accurately today, however— the name of the game is the disclosed invention as claimed.

A review of the disclosure and claims of the recently issued ‘819 patent and the now several years old ‘715 patent tell the whole story and offer a valuable drafting lesson in this new age of eligibility uncertainty.

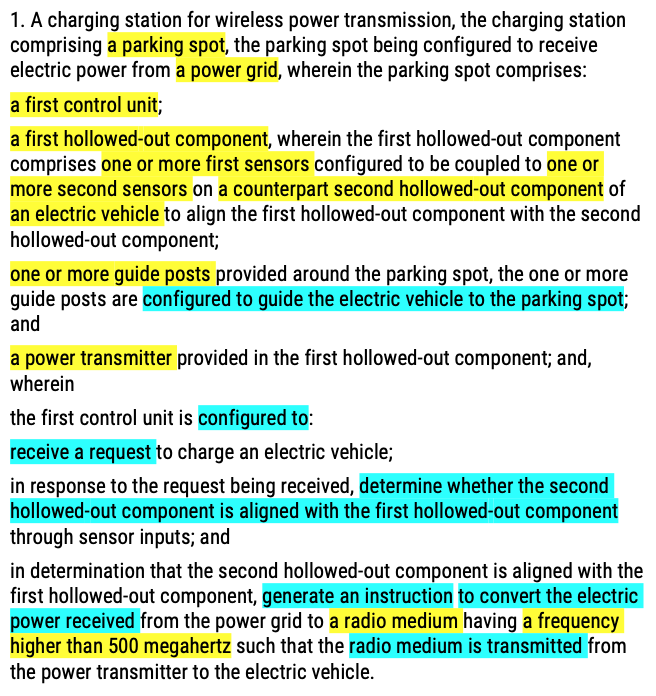

According to the innovation embodied in the ‘819 patent, the claimed invention relates to a vehicle charging station where an electric vehicle is parked in a parking spot configured to receive power from a power grid. There are first and second hollowed out components, which, when aligned, signal that the electric vehicle is in position for the charge to begin. A request is sent to the power grid, received, and then in response to the request, confirmation that the first and second hollowed out components are aligned is made. There is a conversion of the power to a radio medium having a specific frequency of 500 megahertz, with the radio medium with said frequency being transmitted to the electric vehicle for charging.

Below is Claim 1 of the recently issued ‘819 patent, with concrete limitations in yellow and action in blue.

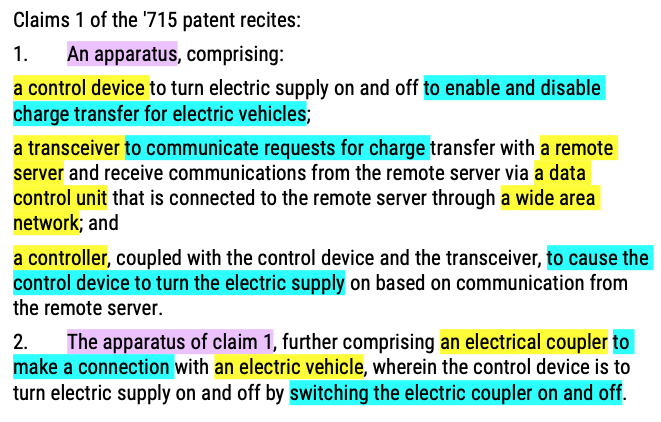

Now compare and contrast this with claims 1 and 2 of the ‘715 patent at issue in ChargePoint: the only two patent claims addressed by the Federal Circuit decision because they were the only two patent claims asserted. In claim 1, the claimed invention is directed to an apparatus with a control device enabled to charge electric vehicles, a transceiver to communicate with a remote service via a wide area network for the purpose of turning the electric supply on. Claim 2 is directed to the same apparatus with an electric coupler that is somehow associated with a control device that supplies an on and off switch. Claim 1 and 2 of the ‘715 patent respectively read, with purple highlight showing the preamble, yellow the concrete limitations, and blue the action:

While the claims of the ‘819 patent are clearly of a more modern vintage than those of the ‘715 patent, let’s begin with what Chief Judge Prost wrote in ChargePoint, saying that it is clear that the claims are both patent ineligible. That is simultaneously both incorrect and correct. It is incorrect under any fair reading of 35 U.S.C. 101, including the admonitions from the Supreme Court, to guard against 101 swallowing all of patent law, and the strict prohibitions in Diamond v. Diehr — which we are continually told are still good law — about not allowing the rest of the statute to do the work for which it is designed. It is, however, sadly a correct statement given the bastardization of patent eligibility by a Federal Circuit that seems afraid to allow 102, 103, or in this case 112, to do the work for which they were designed. Everything must be patent ineligible if there is at all any reason for coming to the conclusion that the claim is abstract without the addition of significantly more, which means significantly different things to different jurists.

But this is the world we live in, a world where Alice has fallen through the looking glass and she can’t get up! So, what are we to do? Learn.

First, the real problem facing the ‘715 patent is that it was filed on March 1, 2011, which means it was prepared, filed and sitting at the Patent Office awaiting prosecution for more than 53 weeks before there even was a Mayo framework, let alone an Alice-Mayo framework, which wouldn’t become a reality until June 2014.

The second major problem facing the ‘715 patent is that it was written at a time just after the Supreme Court said— presumably now in jest— that business methods were still patent eligible. The understanding after Bilski v. Kappos, which will soon celebrate its 10th anniversary on June 28, was that methods describing a process that in part would have money changing hands would not as a matter of law suddenly become patent ineligible. Fast forward to 2020, ten years later, and anyone even vaguely familiar with Federal Circuit decisions involving payment gateways or anything at all financial-related know that even hinting at payment, money, invoices, credit cards or the like is the absolute kiss of death. See e.g. Smart Systems v. Chicago Transit, 873 F. 3d 1364 (Fed. Cir. 2017); Credit Acceptance. v. Westlake Serv., 859 F.3d 1044 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

The claims of the ‘715 patent, which by 2020 standards are quite sparse, did not mention payment, but the specification did violate what has become this absolute rule that must never be violated. The patent reads in part:

“A method of transferring charge between a local power grid and an electric vehicle is disclosed herein. The method comprises the following steps: (1) assembling a user profile, the user profile containing payment information, the user profile being stored on a server; (2) providing an electrical receptacle for transferring charge, the receptacle being connected to the local power grid by an electric power line, charge transfer along the electric power line being controlled by a controller configured to operate a control device on the electric power line; (3) receiving a request to the controller for charge transfer, the request being made from a mobile wireless communication device by an operator of the electric vehicle, the controller being connected to a communication device for communication with the mobile wireless communication device; (4) relaying the request from the controller to the server, the controller being connected to a local area network for communication to the server via a wide area network; (5) validating a payment source for the operator of the electric vehicle based on the user profile corresponding to the operator; (6) enabling charge transfer by communicating from the server to the controller to activate the control device; (7) monitoring the charge transfer using a current measuring device on the electric power line, the controller being configured to monitor the output from the current measuring device and to maintain a running total of charge transferred; (8) detecting completion of the charge transfer; and (9) on detecting completion, sending an invoice to the payment source and disabling charge transfer.”

‘715 patent col. 4 ll. 17-44 (emphasis added).

Obviously, the Federal Circuit knew what the ‘715 patent was all about—it was a a dirty, rotten, filthy, business method.

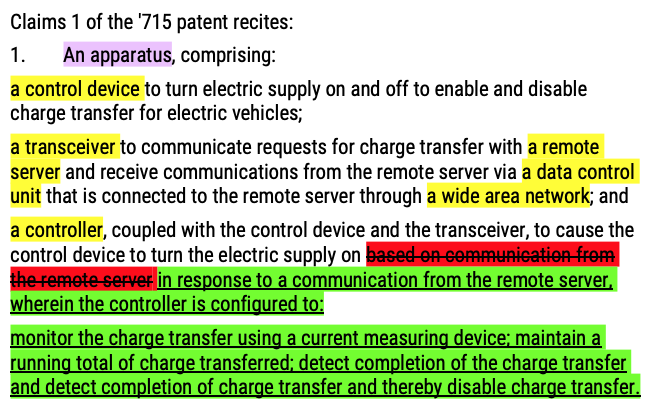

What, if anything, could have been done in hindsight to save the claims of the ‘715 patent? It is unclear, and perhaps unlikely, that there would be anything that could be done by 2020 standards. There is little support from a 112 standpoint, at least based on our understanding as has developed in the Alice/Mayo era. But if the Federal Circuit would not be swayed by disclosure of payment sources and collecting payment disclosed in the specification, here is what could have been attempted.

The Devil is in the (Technical) Details

What follows is a hypothetical re-writing of claim 1 of the ‘715 patent, attempting to stay as true as possible to the specification of the ‘715 patent. In this image, purple represents the preamble, yellow highlight is the concrete limitations, the red is what I’ve removed, and the green is what I propose to add to the claim.

Would this be enough? In a fair world, it would be enough to overcome 101, but this is not a fair world. Regardless, the patent would still likely have issues under 112 because how the monitoring of the charge transfer is accomplished is not described in any real technical detail. Neither is how the detection of a complete transfer is made, for example.

When drafting a patent like this in 2020, you need a thick technical disclosure. What are the technical problems that will be encountered and what are the solutions? For example, how does the system ensure that the battery is not over-charged? Obviously, you must focus the technical description on the point of novelty, otherwise you wind up with an excellent discussion of the prior art. Ultimately, a thick technical description of the prior art is as unhelpful as a cursory description without any technical detail. In the former you lose under 102, in the latter you lose under 101. So, make sure you focus the technical description on what is unique, but engage the inventor in discussion to find out where that unique nugget lies. It will make all the difference.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Copyright: kasto

Image ID: 94325330

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/UnitedLex-May-2-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

16 comments so far.

Reply to “Concerned”

August 6, 2020 02:55 pm@ Concerned: Remember that in order to be patentable, your inventive process must involve more than simply improving the efficiency of an existing process without an unexpected result or synergy of some kind. You’d need to have documented that your invention does more than solve an unmet need using a combination of conventional steps, particularly if it’s a business method.

B

June 28, 2020 07:16 pm@ Concerned “The second examiner admits a long standing problem was solved, but states it was a business problem that was solved.”

And THAT is precisely the issue that the cowardly CAFC refuses to address.

The Examiner has the proper view per the CAFC’s case law. It’s the CAFC that’s retarded.

B

June 28, 2020 05:24 pm@ Jam “While a brick might be patentable, as soon as you add modern technology to the brick (e.g., a processor and memory to track the location of the brick, or perhaps even the price of the brick, such as with an RFID tag), the brick suddenly becomes an abstract idea.”

That may be the best summary of the CAFC’s Alice Corp jurisprudence ever voiced.

B

June 27, 2020 02:23 pmFWIW, Judge Chen isn’t the brightest or most honest legal mind in the business.

Put the new claims in front of Judge Chen and you’ll see the same stupidity that killed Chargepoint.

Jam

June 26, 2020 07:38 pmA significant problem with the ‘715 patent is that it landed on the desks of Judges Prost and Chen. Further, based on the treatment of the ‘715 patent, the ‘819 patent would likely receive the same treatment at the hands of Prost and Chen and have the meaning of the words of the claim be deliberately obscured, disguised, distorted, and reversed to reject the patent.

While a brick might be patentable, as soon as you add modern technology to the brick (e.g., a processor and memory to track the location of the brick, or perhaps even the price of the brick, such as with an RFID tag), the brick suddenly becomes an abstract idea. This is an example of Orwellian doublespeak, where an abstract idea can stub your toe or smash a window.

Jam

June 26, 2020 12:55 pmI was recently reminded of the term “doublespeak” for George Orwell’s 1984. Modern 101 jurisprudence is little more than Orwellian doublespeak. Most opinions rejecting under 101 do little more than use “language that deliberately obscures, disguises, distorts, or reverses the meaning of words”. What would have been a machine in the past is nothing more than an abstract idea today.

TFCFM

June 26, 2020 10:46 amTernary@4: “For anyone who believes: “I don’t think that “power grid” in ‘819 claim 1 is a “concrete limitation” ” I recommend not to stick a metal object into an outlet connected to the “power grid” lest one finds out that the power grid is not an abstract idea at all.”

Although I appreciate the attempted humor, the issue of whether or not a power grid is “abstract” has no bearing on whether it is a concrete limitation of the claim.

Although “the parking spot being configured to receive electric power from a power grid” imposes some limitation on the parking spot, that limitation seems to amount to nothing more than a requirement have a wire or socket somewhere nearby (or at least space to accommodate one of these). The specification perhaps provides better guidance for what this recitation really entails.

Kevin R.

June 25, 2020 10:03 am“Such a result would make the determination of patent eligibility ‘depend simply on the drafts- man’s art.’” Alice citing Flook.

Ternary

June 24, 2020 05:26 pm@4. For anyone who believes: “I don’t think that “power grid” in ‘819 claim 1 is a “concrete limitation” ” I recommend not to stick a metal object into an outlet connected to the “power grid” lest one finds out that the power grid is not an abstract idea at all.

MaxDrei

June 24, 2020 01:29 pmI had always thought that it was not possible for drafters to reconcile the constraints imposed by the US courts with those imposed at top level by the PCT and, subsidiary to that, the regional and national patent laws everywhere else in the world, outside the USA.

But then I read Gene’s final paragraph above, his recommendation to dwell in the specification on problems and solutions, and now start to wonder how much convergence is being driven by the current case law of the US courts.

Thoughts anybody?

Ternary

June 24, 2020 11:59 amFrom an engineering point this article shows how deep we have actually sunk.

A good effort to improve the claims in the ‘715 patent. However, as long as Courts produce nonsense b.s. arguments such as ““[i]t is clear from the language of claim 1 that the claim involves an abstract idea—namely, the abstract idea of communicating requests to a remote server and receiving communications from that server, i.e., communication over a network.” ” we are pretty much screwed and no efforts of any attorney or applicant can foresee or forestall these arbitrary decisions.

I agree that it is wise to at least try not to hand the Courts obvious reasons to apply Alice, if one continues with pursuing a patent. I mean, these guys are nutty enough to come up with unreasonable arguments against reasonable facts. You really don’t have to just hand it to them.

In that sense I was truly surprised to see the ‘819 patent claim a “radio medium.” What the heck is that? It seems to mean e.m. radiation. But a radio medium can also be considered to be the “aether.” The spec does not further explain “radio medium”. It only repeats the claims in the summary, but no explanation of “radio medium” is provided in the spec. But who knows, perhaps judges are still fully convinced there is an aether.

I reviewed the case history on that in Public Pair. But the Examiner seems not to care about “radio medium.” I am pretty sure the Courts will eventually.

To my further surprise, the original (and later amended) independent claim in the ‘819 is not really about “charging” but about the inventive use of a “vacuum generator” which in the issued patent has completely disappeared. The “radio medium” is ancillary to the claim (and possibly included as such to circumvent Nuijten issues) but may eventually sink the patent.

Andrew Berks

June 24, 2020 10:31 amThe problem with the original ‘715 claim is there is no problem solved at the end. An electric supply is turned on, but so what? What does the electric supply do? If there was a concrete action like “and thereby charge a vehicle” that might solve the problem. The ‘819 claim provides such an action step. Claims should accomplish something. Turning an electric supply on is insufficient without being explicit on what the electric supply is for.

TFCFM

June 24, 2020 10:21 amTwo observations:

1) The mere fact that the ‘819 patent issued does not, of course, mean that its claims are valid (even if a court must initially presume that they are) or that its claims are fully compliant with the requirement of the patent statute.

2) I am skeptical that the ‘revised’ claim 1 of the ‘715 would be considered any less abstract than the original claim. Like the original, it still recites a mere combination of a generic “control device,” a generic “transceiver” (coupled by the preposition “to” to a mere intended function), and a generic “controller.” The added recitation that the controller is “configured to” perform certain function perhaps slightly lessens the generic-ness of that component, but surely not of the claim overall. The claim continues to recite merely the combination of i) anything that performs the intended functions of a “control device,” anything that performs the intended function of a “transceiver,” and anything that performs the intended function of a “controller.” Another name for this assembly is, of course, “anything that works to perform the functions I have listed.” That is probably as close to a definition of “generic” as I have seen.

Claim 1 of the ‘819 patent includes this generic-ness fault in its “first control unit” element, but that is “forgiveable” (eligibility-wise) because the claim recites other non-generic structure (first and second hollowed-out components, first and second sensors, guide post(s), parking spot, and power transmitter) sufficient to make the claimed charging station more than a mere collection of intended functions.

2 1/2) I question whether any of the “remote server,” the “data control unit” , and the “wide area network” are “concrete limitations” (as the article suggests), either in the original ‘715 claim or the revised version. The element that is recited is a “transceiver to communicate…with… and receive… from” those items. This appears to me to be a statement of the intended function (or, at best, required functional capacity) of the “transceiver,” rather than components of the claimed “apparatus.” (FWIW, I don’t think that “power grid” in ‘819 claim 1 is a “concrete limitation” for the same reason.)

Mark Nowotarski

June 24, 2020 10:18 amAnother important step is to file continuing applications. That way you can adapt to the changing 101 landscape. ChargePoint had the good sense to file continuing applications of which two are still pending. I suspect their pending claims are being drafted in light of the guidance of their CAFC decision.

Concerned

June 24, 2020 07:13 amMy patent application has 14 limitations and only 3 have ever been addressed in the prosecution.

When the first examiner cannot offer a reasonable rejection, a new examiner is mysteriously assigned. The first examiner did admit in a phone interview 3 times the application is patentable, upstairs was the problem.

The second examiner admits a long standing problem was solved, but states it was a business problem that was solved. Of course this alleged business problem has working professionals, experts, attorneys across the nation, a vast computer network and universities that have failed for six decades to solve the problem. All fully documented in the official record.

The second examiner also makes numerous unsubstantiated statements to include the solution only automates a manual process. What manual process, none was offered by the examiner and I am not aware of one after 44 years experience?

The inventative concept is clearly in the specs and the claims, both examiners never offered even one example in any field of commence where the inventative concept is used, let alone an example in my field of commence.

I am hoping, in the possibility of intrigrity, the first examiner told upstairs to find someone else to carry their water, then here comes examiner number 2. That would be a small consolidation to me.

Accordingly I feel that certain applications are going to be rejected regardless of what is in the specs and claims, no matter what problem the “new and useful” solution is solving.

Big Tech seems to get all kinds of patents approved. Therefore, I submit, the name of the game is the claim, unless you’re in the desert with a horse with no name.

Pro Say

June 23, 2020 09:23 pm“At the same time, we tread carefully in construing this exclusionary principle lest it swallow all of patent law. Mayo, 566 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 2)”

Careful treading?

Nowhere to be seen.

Nowhere to be found.

No one to enforce.