“While this case may be disheartening for those who would seek to broaden the scope of protection obtainable via a design patent to surface ornamentation separable from an article of manufacture, it should be useful to those facing Section 102 rejections over non-analogous art in design cases.”

Source: CAFC opinion

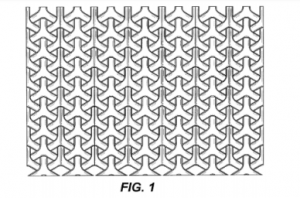

In Curver Luxembourg SARL v. Home Expressions, Inc. (CAFC, Sept. 12, 2019)—which already has become a rather infamous design patent case—the claims at issue recited an “ornamental design for a pattern for a chair,” while the figures illustrated only the fabric pattern, not associated with any article of manufacture. The alleged infringing article was a basket, and the Federal Circuit held “because we agree with the district court that the claim language “ornamental design for a pattern for a chair” limits the scope of the claimed design in this case, we affirm.”

Prosecution History and District Court

Source: CAFC opinion

Curver had originally titled their application “FURNITURE (PART OF-)’, though no figures illustrated any piece of furniture, or portion thereof, instead showing only a portion of a fabric structure. The examiner required amendment, citing 37 CFR 1.153 and MPEP 1503(i) both of which require the title to designate a “particular article” for the design, and holding that reference to a “part of” a piece of furniture rendered the title vague. The examiner suggested amendment to “Pattern for a Chair” and further suggested that the same language be adopted through the specification. Curver complied.

The district court applied a two-step infringement analysis—first construing the scope of the patent to be limited to the pattern illustrated, applied to a chair, offering the explanation that “the scope of a design patent is limited to the article of manufacture…listed in the patent.” The district court proceeded to find that an ordinary observer would not mistakenly purchase Home Expressions’ basket believing it to be a chair bearing the same pattern. Curver appealed.

First Impressions and Claim Limitations

On appeal, Curver argued that the district court’s focus on the language of the title “Pattern for a Chair” was unduly limiting, as the Figures did not illustrate a chair. The Federal Circuit responded to this argument as follows:

Given that the figures fail to illustrate any particular article of manufacture, Curver’s argument effectively collapses to a request for a patent on a surface ornamentation design per se. As Curver itself acknowledges, our law has never sanctioned granting a design patent for a surface ornamentation in the abstract such that the patent’s scope encompasses every possible article of manufacture to which the surface ornamentation is applied. Curver slip opinion, pages 6-7.

Curver did present the argument that the portion of the fabric structure shown in the figures represented an “article of manufacture” as the portion shown was a component of a product in the same way a component of a multicomponent smart phone is the required article of manufacture. The Court first held the argument waived as being presented for the first time on appeal, but also differentiated the two:

…the components covered by Apple’s design patents were parts of a concrete multicomponent smartphone product, not a surface ornamentation disembodied from any identifiable product, as here. Slip opinion, footnote 1.

The Court went on to classify the case as one of first impression, “where all of the drawings fail to depict an article of manufacture for the ornamental design,” and “whether claim language specifying an article of manufacture can limit the scope of a design patent, even if that article of manufacture is not actually illustrated in the figures.” The Court then held:

Given that long-standing precedent, unchallenged regulation, and agency practice all consistently support the view that design patents are granted only for a design applied to an article of manufacture, and not a design per se, we hold that claim language can limit the scope of a design patent where the claim language supplies the only instance of an article of manufacture that appears nowhere in the figures.

The Court continued to address Curver’s arguments in turn, first dispensing of Curver’s argument that the district court had improperly applied prosecution history estoppel to limit their claim, with the statement:

Because the “pattern for a chair” amendments were made pursuant to 1.153 requiring the designation of a particular article of manufacture, and this requirement was necessary to secure the patent, we hold that the scope of the ‘946 patent is limited by those amendments, notwithstanding the applicant’s failure to update the figures to reflect those limiting amendments.

With respect to Curver’s attempted reliance on In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447, 450 (CCPA 1956) for the proposition that an article of manufacture can be anticipated by a non-analogous article bearing the same surface ornamentation, the Court held:

Contrary to Curver’s assertion, Glavas’s [sic] dictum did not state that a design patent disclosing a surface ornamentation applied to a given article…can be anticipated by an unrelated article having a very different physical appearance and form…Here, there is no dispute that a basket embodying a particular ornamental pattern is not substantially similar in appearance to a chair embodying that same pattern such that the former would infringe a design patent covering the latter.

Disheartening for Some, Useful for Others

While this case may thus be disheartening for those who would seek to broaden the scope of protection obtainable via a design patent to surface ornamentation separable from an article of manufacture (which the Court takes care to say is within the sole purview of copyright protection), what the Court takes on one hand, it gives on another.

After stating that even if the “dictum” of Glavas allowed anticipation by an article of manufacture that looked completely different than the claimed article, that dictum would be controlled by Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc.. The Court continued:

Because we use the same test for determining infringement and anticipation, the ordinary observer test is now the sole controlling test for determining anticipation of design patents too…Under this ordinary observer test, Curver does not dispute that the district court correctly dismissed Curver’s claim of infringement, for no “ordinary observer” could be deceived into purchasing Home Expressions’s [sic] baskets believing they were the same as the patterned chairs claimed in Curver’s patent.

This holding should thus be useful to those facing Section 102 rejections over non-analogous art in design cases.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Anon

September 18, 2019 11:53 amI have to question ANY “usefulness” under 102 in light of any (actual applied) 103.