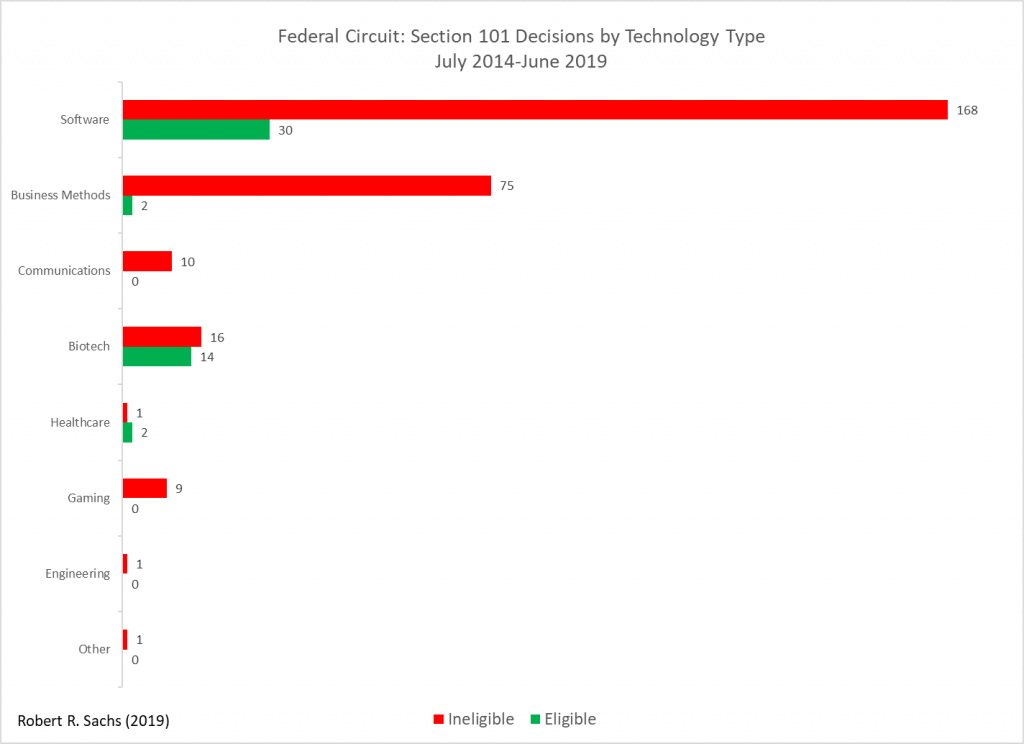

“While the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos made it clear that there is no categorical exclusion of business methods from the Patent Act, the Federal Circuit has more or less behaved otherwise, as it has found only two out of 77 business method patents since Alice to be eligible.”

An older version of this article was originally commissioned for and published in IAM. It features in issue 96 of the magazine, which came out in June 2019 (www.iam-media.com)

In Part I of this analysis, I discussed litigation trends before and after the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice Corp Pty Ltd v. CLS Bank Int’l., which turned five this year. In Part II, I will break down the data further by examining how the court decide Section 101 motions according to the underlying patented technology.

The Technology Breakdown

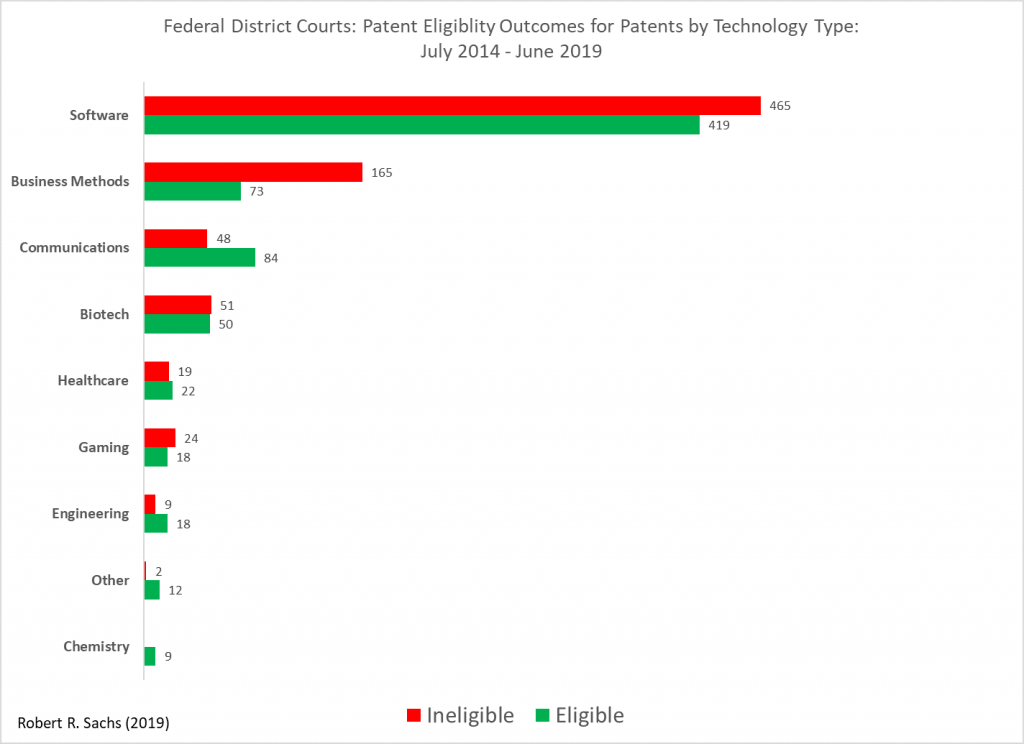

Figure 11 shows the distribution of technology types of patents subject to Section 101 motions for the district courts:

Figure 11

Alice’s regime started with the invalidation of business method patents, as these types of patents tend to draw the most criticism and have the highest rate of ineligibility (69%) at the district courts. However, Figure 11 shows that software patents are by far more frequently attacked than business method patents, and the invalidation rates are slightly in the defendant’s favor (53% ineligible). Overall, biotech patents also have been a coin toss (51% ineligible). Communication patents have fared better overall (36% ineligible).

Figure 12 illustrates the technology breakdown of the patents considered by the Federal Circuit specifically.

Figure 12

The Federal Circuit has shown significantly greater hostility to software patents than the district courts, finding ineligible subject matter in 85% of the litigated software patents. And while the Supreme Court in Bilski v. Kappos made it clear that there is no categorical exclusion of business methods from the Patent Act, the Federal Circuit has more or less behaved otherwise, as it has found only two out of 77 business method patents since Alice to be eligible—both in Trading Technologies v. CQG (2017), though this decision was non-precedential.

PTAB: Queen Alice’s Executioner

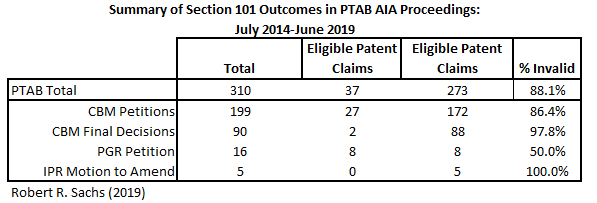

Finally, the PTAB has been the most aggressive enforcer of Queen Alice’s rule. Figure 13 summarizes the outcome of America Invents Act proceedings that raise Section 101 attacks.

Figure 13

In addition, while Section 101 cannot be considered as a basis for an IPR, once the patent owner moves to amend the claims, the PTAB can consider patent eligibility of the amended claims. To date, the PTAB has considered this issue five times, and has found the proposed claims ineligible in each case.

Good for Some, Bad for Many

Your interpretation of these facts depends on your point of view—a suitably post-modern outcome for some, less so for others. If you are a rights holder or licensor who depends on the objective certainty of patent rights, then the numbers are merely a grim confirmation that bad patents and bad science make for bad law. The consistency that Alice brings to litigation is, at best, the epistemic certainty that a patent on just about any kind of technology can be subject to a motion to dismiss for ineligible subject matter—and that nearly 60% of such attacks succeed in the district courts and are then affirmed over 85% of the time on appeal to the Federal Circuit. You agree with the assessment that Alice’s edict is a fancy I-know-it-when-I-see-it shorthand for deciding whether patent claims have so-called “inventive merit”—an approach that Judge Plager described in Interval Licensing v. AOL (2018) as providing “no discernable boundaries for decision-making in specific cases, resulting in an incoherent legal rule that led to arbitrary outcomes.” This observation echoes that of Judge Rich, the author of the 1952 Patent Act, who carefully crafted Section 101 to rationalize the patent eligibility law, stating that: “Nowhere in the entire act is there any reference to a requirement of ‘invention’ and the drafters did this deliberately in an effort to free the law and lawyers from bondage to that old and meaningless term.”

Nonetheless, what Congress taketh away, the Supreme Court sees fit to restore. With Alice, the snipe hunt for an invention is back, only this time it is typically a proxy for invalidating patents for obviousness, lack of written description or enablement without the costly need for the niceties of evidence. As a technology-savvy patent holder you view the Federal Circuit’s decisions as inconsistent at best and based on an arbitrary division between claims using a computer as a tool (generally ineligible) and claims for improving the computer itself (generally eligible). Of course, you know that computers are inherently tools to do something useful, and that Alice‘s mention of “improving a computer” was an example of an eligible transformation, not a requirement of one. Your experience before the USPTO has been similar, and until recently, patent examination of your company’s software and/or biotech inventions have been dominated by Section 101 rejections, increasing your prosecution costs and the time to issuance. The value of your patents has dropped—sometimes to zero—and some licensees have aggressively attempted to renegotiate their agreements.

On the other hand, if you are a company that is a target of patent assertions, then these numbers are cause for celebration: Queen Alice has made the world a better place by reducing your exposure to both the meritless claims of existing patents and—better yet—the possible universe of future patents that could have been used against you. If you have had to forego patent protection of your own by not filing, abandoning a few applications here and there, or just dealing with increased prosecution costs, it has been a small price to pay for the increased likelihood of successful outcomes as a defendant in patent litigation. Queen Alice has been benevolent and wise, and objections to her rules are merely the Talmudic carping of patent maximalists and persnickety patent attorneys. You wholeheartedly endorsed the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s recently abandoned Save Alice campaign, possibly humming “God Save The Queen” to yourself each time you read of potential legislation to abrogate the Supreme Court’s trilogy of Section 101 decisions.

In my view, the five-year reign of Queen Alice is like that of many autocrats—good for some, bad for many, and decidedly painful for a few. With the prospect of Section 101 reform being seriously considered by members of Congress, I’m cautiously hopeful that this reign will end soon.

The statistics in this article were derived in collaboration with my colleagues Christopher King and Cullan Bendig at Fenwick & West, LLP.

Image Source: Deposit PHotos

Photography ID: 48526335

Copyright: TroschaMad

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Artificial-Intelligence-2024-REPLAY-sidebar-700x500-corrected.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

2 comments so far.

Pro Say

September 3, 2019 06:21 pmCouldn’t have said it any better, Software Inventor.

Congress simply must end this pox on American innovation.

Now; this month.

Please.

Software Inventor

September 3, 2019 02:58 pmThanks to the researchers and author of this empirical data that clearly shows the decimation of inventors in this country at the betrayal of the US Congress and USPTO. (I suggest one more data category will be helpful if the author could provide: what percent of the patent applicants/owners were micro and small entity?)

The US Congress allowed the courts to create their own exceptions; bought the “troll” narrative by big tech (their legal and marketing departments created “troll” to defame their infringement plaintiffs to protect their brands, i.e. admit nothing, deny everything, and make counter accusations) to con the Congress into passing AIA; and the USPTO for unleashing their corrupt PTAB IPR APJ hacks onto their product owners decimating inventors and their livelihoods – all the while the Director only recounts pre-eBay inventor profiles in this keynote speeches. The current reality is clearly presented in the data – so let’s start saying so.

The lying and obfuscation by the anti-patent can now stop – and their enablers in Congress can no longer turn a blind eye. The patent system and persecuted inventors must be made whole again, for the benefit of the country and future economy (and servicing our annual deficits and national debt.)