“Another emerging (and perhaps troubling) theme since Octane Fitness is that certain conduct by parties, even if ‘obnoxious, and arguably unethical’ may not be found exceptional, particularly where it had no significant impact on the outcome or did not lead to any material activity in the litigation.”

Five years ago, on April 29, 2014, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Octane Fitness LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., empowering district courts to award attorneys’ fees in those patent case that “stand out from others.” Last year, we crunched the numbers and explored several notable trends that have emerged post-Octane Fitness. For that article, we looked at nearly 420 decisions spanning nearly four years. In the last 14 months, district courts have been asked to declare patent cases exceptional another 165 times. Below, this article revisits the statistics and takes a deeper look at the line between zealous advocacy and litigation misconduct that can serve as the basis of an exceptional case determination.

Five years ago, on April 29, 2014, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Octane Fitness LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., empowering district courts to award attorneys’ fees in those patent case that “stand out from others.” Last year, we crunched the numbers and explored several notable trends that have emerged post-Octane Fitness. For that article, we looked at nearly 420 decisions spanning nearly four years. In the last 14 months, district courts have been asked to declare patent cases exceptional another 165 times. Below, this article revisits the statistics and takes a deeper look at the line between zealous advocacy and litigation misconduct that can serve as the basis of an exceptional case determination.

Checking in on the Numbers

Overall

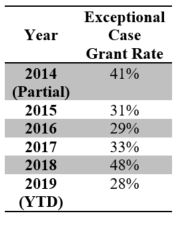

The last 14 months saw an uptick in the number of exceptional case decisions issued by district courts. In 2017, there was an average of 8.5 decisions per month. For the last 14 months, the rate is closer to 10.5 decisions per month. By February last year, there were already signs that 2018 may yield a higher grant-rate than previous years. That proved to be true, with courts declaring cases exceptional nearly 50% of the time in 2018. In the first four months of 2019, the grant rate has dropped back to 28%. And the overall grant-rate post-Octane Fitness remains steady at 33%.

The last 14 months saw an uptick in the number of exceptional case decisions issued by district courts. In 2017, there was an average of 8.5 decisions per month. For the last 14 months, the rate is closer to 10.5 decisions per month. By February last year, there were already signs that 2018 may yield a higher grant-rate than previous years. That proved to be true, with courts declaring cases exceptional nearly 50% of the time in 2018. In the first four months of 2019, the grant rate has dropped back to 28%. And the overall grant-rate post-Octane Fitness remains steady at 33%.

Patent Owners vs. Accused Infringers

Accused infringers continued to file more exceptional case motions than patent owners over the last 14 months, but by not nearly as wide a margin. From April 2014 through the beginning of 2018, the vast majority of exceptional case motions—over 75%—were filed by the accused infringers. Over the past 14 months, however, there was more balance between motions filed by patent owners and accused infringers. Since February 2018, accused infringers filed just over 55% of exceptional case motions.

The near parity between motions filed by patent owners and accused infringers provides at least some basis for the uptick in the grant rate in 2018. Patent owners are generally more successful than accused infringers in convincing courts to declare cases exceptional. Over the last 14 months, accused infringers succeeded in only 25% of the motions filed; whereas, patent holders were successful nearly 46% of the time. Of the decisions on patent holders’ motions, 19 involved defaults, where the grant rate was significantly higher at 84%. Removing the cases where defendant defaulted, patent holder still prevailed approximately 32% of the time. These numbers are consistent with the trends observed last year.

Location, Location, Location

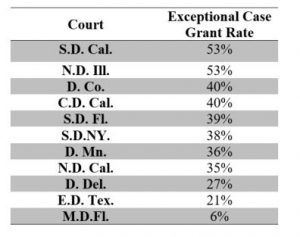

Once again, nearly half of the most recent decisions came from five of the most patent-intensive dockets: the Eastern District of Texas, Central District of California, Northern District of California, District of Delaware, and Southern District of New York. Additionally, overall grant rates within districts have remained relatively steady, although the Central District of California and Northern District of California saw jumps with grant rates over the last 14 months of 44% and 56%, respectively, and the Southern District of New York, Eastern District of Texas, and District of Delaware saw declines in overall grant rate—29%, 12%, and 12% respectively. An updated table accounting for all decisions through April 15, 2019 is set forth in the chart (right).

Zealous Advocacy or Litigation Misconduct?

Courts often are asked to grapple with the question of whether a losing side’s litigation tactics are “exceptional” enough to warrant an award of attorneys’ fees. In Octane Fitness, the Supreme Court instructed that “sanctionable conduct is not the appropriate benchmark” for a district court to award attorneys’ fees; rather, “a district court may award fees in the rare case in which a party’s unreasonable conduct—while not necessarily independently sanctionable—is nonetheless so ‘exceptional’ as to justify an award of fees.” In practice and application, district courts evaluate the tactics employed in the case at issue to those tactics district courts perceive to be ordinary or typical in patent litigation.

What Is Not Exceptional Conduct in Patent Litigation?

District courts consider a wide range of litigation conduct to be unexceptional in patent cases. At the outset, courts recognize that aggressive litigation strategies are inherent in patent litigation. One court explained that although the litigation was “hotly contested” and “marked by a tremendous number of disputes,” this was a typical reality of high-stakes competitor patent litigation. As other courts put it, certain tactics are “not unusual for a case of this size and complexity” and are typical of “hard fought patent litigation between competitors.” Another emerging (and perhaps troubling) theme is that certain conduct by parties, even if “obnoxious, and arguably unethical” may not be found exceptional, particularly where it had no significant impact on the outcome or did not lead to any material activity in the litigation. To this end, a court may not deem aggressive litigation conduct “exceptional,” even if it is potentially “worthy of condemnations and sanctions,” where there is no real impact stemming from the conduct.

In the same spirit, discovery disputes and motions to compel are viewed by courts as common in nearly all patent cases and alone do not amount to inappropriate or unreasonable conduct by a party. Vague allegations of a lack of transparency in discovery likely will not suffice. As one court put it, “bitter discovery disputes” are simply “par for the course.” Similarly, one court found with respect to a motion for reconsideration rearguing points that a party had already made that this approach “is common, not exceptional” and that it denied nine of ten motions to reconsider on that basis.

Courts also tend to be understanding of parties’ settlement strategies. As a general rule, evidence of low—even unreasonable—settlement offers alone are not grounds for fees. One court reasoned that parties often have very different views about the value of a case. Where unreasonably low settlement offers evidence a nuisance case, however, courts remain more likely to grant the motion. As one court put it, “it is axiomatic that a plaintiff should want a case to be heard on its merits” and where patent holder did not and instead “was fishing for settlements,” a fee award was appropriate. In another decision, a court noted that the number of actions combined with the “nuisance-value settlements right before a merits determination” supported the award of attorneys’ fees.

It bears mentioning here that the totality of the circumstances and both parties’ conduct will be considered by district courts. In at least one instance in the past year, a court found that the accused infringer’s own bad acts and unreasonable conduct prevented an award of attorneys’ fees, as the movant must have “clean hands.” In another case, the court pointed to the fact that both parties had engaged in “excessive motion practice, dilatory tactics, and histrionic argumentation,” and attributed fault to both for the length of the litigation.

Defining Exceptional Conduct

Courts have shown a willingness to find that litigation misconduct merits a fee award in situations where conduct has led to prolonged and unnecessary litigation, driven up costs, and wasted judicial resources. For example, one court based its award of fees on a finding that the “overall strategy” of the party was to force the other to “expend large amounts of money in a lengthy and protracted litigation.” Another found that a party “unnecessarily complicated the proceedings and needlessly increased costs” where it repeatedly argued positions that had been rejected, purposefully ignored court orders during discovery, and disclosed a “completely unreasonable” number of obviousness combinations in its contentions.

In addition, there is certain conduct that is more likely to contribute to a finding of attorneys’ fees. For example, refusing to comply with court orders, failing to appear in court, and habitually submitting untimely or procedurally non-compliant papers; excessive motion practice that seems to have “no legitimate purpose” other than burden and delay; producing inaccurate records and making misrepresentations; intentional stalling tactics; deceptive acts such as purposefully redacting discovery to conceal material information from the other side. One of the more interesting decisions regarding party misconduct involved a situation where defendant hired the former firm of the judge overseeing the case to prompt his recusal. The court viewed the hiring of the firm to prompt the judge’s recusal as an attempt to avoid an adverse finding, and while it noted that the conduct may not have been sanctionable, it was exceptional for the purpose of a fee inquiry.

A lack of good faith cooperation and gamesmanship may be deemed misconduct sufficient for a fee award. For example, courts awarded fees in the following situations: where a party filed a notice of dismissal, covenant not to sue, and motion to dismiss without first notifying defendant’s counsel on the same day pretrial submissions were due; where a party, among other things, failed to explore settlement before or after the outcome of a pending inter partes review; where a party prematurely filed a summary judgment motion and then waited to withdraw a declaration until after the opposing party had incurred significant expense in filing its opposition; and where a party changed its infringement theories but did not amend its contentions. In one notable example of a grant of fees in a case arising under the Hatch-Waxman Act—where fee awards are rare—the District of Delaware found in Cosmo Technologies Ltd. et al. v. Actavis Laboratories FL, Inc. that where the patent holder maintained 35 asserted patent claims until two weeks before trial and dropped two patents without warning two business days before trial “the timing and circumstances . . . was unreasonable, prejudicial to Defendants, and reflective of the substantive weaknesses” of patent holder’s case.

A Steady But High Bar

On the fifth-year anniversary of Octane Fitness, grant rates remain relatively steady, and district courts continue to engage in a case-specific, flexible inquiry that permits litigants opportunity to recover fees when faced with baseless claims or unreasonable conduct by the opposing party. Litigants should bear in mind, however, that when it comes to litigation misconduct, recovery is most likely where there is a pattern that is outside the realm of the typical case and where they can point to some material impact on the course of the case.

Image Source: Deposit Photos

Photo by nbvf89

ID: 10026598

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.