Any patent attorney knows that the behavior of patent examiners can vary greatly. In this article, I describe five different types of patent examiners and suggest prosecution strategies for each to help you get better outcomes for your clients.

The Master Patent Examiner

The Master is a patent examiner with a low grant rate but who is also exceptionally good at his or her job. Masters are able to find good prior art for just about every patent application that comes across their desk, and they thus have high affirmance rates on appeal.

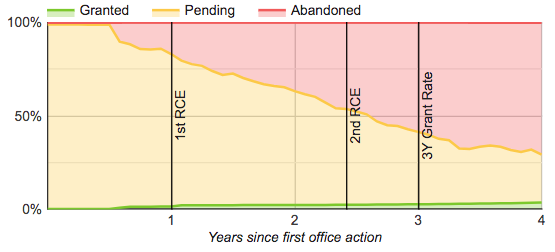

Here is an example grant rate timeline for a Master:

Source Patent Bots

This grant rate timeline shows the percentage of cases that are allowed (green), pending (yellow), and abandoned (red) at each month after the first office action. This Master has allowed only 2.5% of applications at three years after the first office action and is in the 97th percentile for examiner difficulty across the USPTO.

On appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), this examiner is affirmed 94% of the time. This Master is thus able to find good prior art, write convincing arguments, and persuade the judges nearly all of the time.

Recommended strategy: Narrow your claims and work hard to write persuasive arguments.

The Ideologue

The Ideologue also has a low grant rate, but for reasons of ideology rather than the merits. A significant number of patent examiners appear to be “anti-patent” and refuse to grant patents for worthy inventions. This is the most frustrating type of patent examiner for a patent attorney because strong arguments fall on deaf ears.

An Ideologue will have a grant rate timeline similar to the one shown above for the Master. The difference between the two, however, is easily seen in the appeals statistics.

A first characteristic of an Ideologue is a low affirmance rate on appeal. An Ideologue does not have good arguments for refusing to allow claims, and thus the PTAB often finds for the applicant.

A second characteristic of an Ideologue is a high rate of reopening prosecution during the appeal process. Some Ideologues frequently issue an office action after the appeal brief has been filed, thus presenting resolution by the PTAB. This appears to be a strategy to avoid allowance by keeping prosecution open indefinitely.

For more junior examiners, the ideologue behavior may be caused by the primary examiner or SPE who reviews the junior examiner’s work. As a result, for some examiners, there is a significant change in grant rate after the examiner becomes a primary examiner.

Recommended strategy: Appeal early and consider contacting the examiner’s supervisor for assistance.

The Decider

The Decider is an examiner who makes up his or her mind early during prosecution and won’t be convinced otherwise. You could call them stubborn or hard headed.

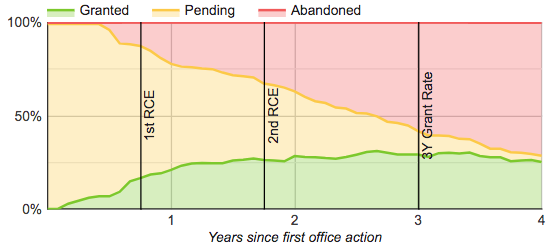

Here is an example grant rate timeline for a Decider:

Source Patent Bots

A Decider usually makes up their mind by the first RCE. Even if you continue for many years with many RCEs, you will unlikely be able to convince them otherwise.

Recommended strategy: Once you get to a second final rejection (after a first RCE), then appeal.

The Negotiator

A Negotiator is an examiner who will continue to work with applicants to come to a compromise and find allowable claims. The more you continue to work with a Negotiator, the greater your chance of getting claims allowed.

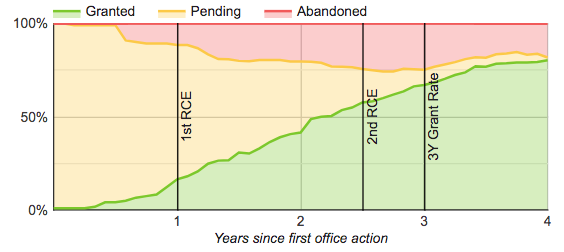

Here is an example of a grant rate timeline for a Negotiator:

Source Patent Bots

As you can see, even after three years of prosecution, continuing to work with the examiner will increase your chances of getting claims allowed.

Recommended strategy: Continue to work with the examiner and work harder to find alternative patentability arguments or a compromise. Interview early and often.

The Granter

A Granter is an examiner who grants a lot of patents and does so quickly! While it is nice as a patent attorney to be able to get a good outcome for your client, there is also a risk that the examination was less than thorough and that your patent may be more susceptible to invalidation in the future.

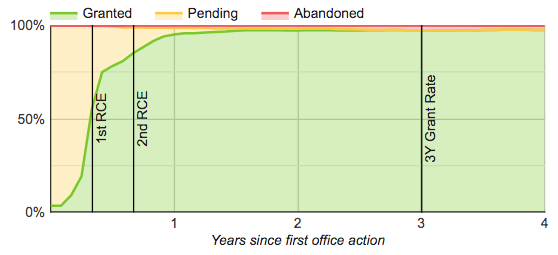

Here is an example of a grant rate timeline for a Granter:

Source: Patent Bots

At one year after the first office action, this Granter already has a grant rate of 95%. Granters often have early RCEs, and I suspect this occurs because applicants need to file an RCE to submit additional prior art (e.g., there was a first action allowance and the applicant hadn’t yet filed an IDS).

Recommended strategy: Add more dependent claims so you have a stronger patent in case there is good prior art for your independent claims.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

20 comments so far.

Anon

February 3, 2019 10:22 amBenny,

I do NOT have that backwards.

Yes, a client can (does, and in certain situations, most definitely should) fire its counsel.

But you only show your lack of understanding with your post by not recognizing that clients ALSO can (are, and in certain situations, most definitely should be) fired.

Counsel has an ethical duty to best serve the clients they DECIDE to represent. But make no mistake, counsel retains the decision power TO represent (with certain constrainst, of course).

As typical, your post serves to reinforce the point I present. In that sense, I thank you.

Benny

February 3, 2019 02:17 amCP in DC, (@17),

I work for one of those “count the patent numbers” people, and if you are wondering if it is frustrating, wonder no more, the answer is yes.

There is also a 6th type of examiner, the consistent examiner. However, this examiner exists in theory only, and no live example has yet been observed at the USPTO (or the EPO, for that matter).

Anon, as for your advice to CP to fire the client, you’ve got is a-ess-ess backwards. You don’t fire us. We fire you.

Anon

February 2, 2019 10:32 pmCP in DC,

I would be truly (and professionally) embarrassed to be in that group on anything more than a rare occasion.

Think: firing the client.

Further, if that is indeed what is “desired,” then a move to a pure registration system is what needs to take place. Elsewise, the multi-BILLION annual bill FROM innovators to fund the patent office is an atrocious (nigh criminal) waste of money.

CP in DC

February 2, 2019 05:10 pmAnon @ 13

Yes, the answer is yes. I know of many many many patent prosecutors that only want the allowance regardless of claim quality. Enforcement is never considered. Clients are happy to have one or several “patents” without realizing the unenforceability of the claims. Get the patents fast and often is the mantra.

A patent portfolio with many patents always looks better than a few great patents that no one (PTAB included) can break. Those judging don’t know how to gauge claim quality, enforceability, or infringement. Those that invest in companies, buy patents, and even NPE just go in blind and hope for the best.

Evaluating patents is hard, so most don’t bother. If those buying patents or investing are not judging, then getting past the “granter” is the only goal. It’s a shame but true.

CouchPotato

February 2, 2019 11:59 amPretty graphs, but not much useful substance. I doubt the author was trying to come up with a precise examiner classification, but simply wanted to drive traffic to his business website and from that point he probably succeeded.

But this reminds me of Cosmo’s “5 Types of Guys You Shouldn’t Date” articles… Can’t neatly group thousands of examining corps into 5 categories, especially without taking specific AUs into consideration.

Night Writer

February 2, 2019 07:38 amJust to reiterate, I think that the types of examiners is highly dependent on the AU. There are different types within the AUs, but they are different.

Anon

February 1, 2019 07:30 pmDoes one really want to (merely) get past the “Granter”…?

Sure, there are business reasons for obtaining grants (with no view to actually enforcing those grants), but by and large, not wanting a grant that has been properly examined is a losing gambit.

Night Writer

February 1, 2019 03:59 pmI would try to break this down by AU. Plus, I think you need what happens after the first NFOA vs. first FOA.

I think there are a lot of examiners that want to allow after the first NFOA as they get an interview and all the points and the FOA is just extra work.

But, AU is a huge part of this.

I think a lot has to do with whether the client is willing to appeal as well. And how close to the orginal claims the client wants allowed.

XYZABC

February 1, 2019 01:04 pmIs it so one-sided? There are two other important variables to consider here – the patent agent ‘type’ and the client ‘type’.

And all the wonderful combinations thereof.

Jeff

February 1, 2019 11:31 am@Mark, thanks! The time scale is from the date of the first office action on a monthly basis for up to 4 years. The RCE lines indicate the average dates of the first and second RCEs. You can see more details at the Patent Bots website.

TMier

February 1, 2019 09:46 am@Anon 7 – I agree that having the examiner proactively hunt down unclaimed-yet-patentable aspects of the applicant’s invention would speed up prosecution, but I don’t believe that it’s reasonable.

There’s a huge world of prior art out there; more than any one person can absorb and retain. I honestly don’t know if there’s something in an application that’s patentable unless I conduct an exhaustive search, and unless it’s in the claims, I’m not searching for it. The inventor(s) are in the best position to point out the novel aspects of their invention, and the claims are the place to do it. There’s not enough time for me to search for facets of the invention that the inventor hasn’t even bothered to claim.

I might be able to tell an applicant during an interview “here’s an unclaimed aspect of your invention that I don’t recall seeing before and didn’t come across in my search,” but that’s as far as I can go regarding novelty and non-obviousness without a further search.

Mark Nowotarski

February 1, 2019 08:30 amJeff,

Great graphics. Can you say more about the time scale? I’m not quite sure what you are indicating or what “1st RCE” and “2nd RCE” indicate.

concerned

February 1, 2019 12:44 amI cannot decide which examiner I have: The Master, The Ideologue or The Decider.

Regardless, and as a previous public servant for decades, I do not appreciation spending good money to be rejected by a public servant with a reasoning that is not truthful, not factual and not logical.

The examiner will not address the evidence, will not address their official memos, or will not use arguments in my field of technology (another requirement of their own MPEP). He just babbles the standard “cut and pasted” rejection statements per the author whom included my story in his upcoming book.

In effect, the examiner insults the experts and professionals in my field, who failed to find my long sought solution of 62 years, by rendering a decision that is clearly non-responsive as if every expert/professional is a moron in my field for not seeing this solution that is so-called conventional, routine and well understood.

The only thing that is well understood, conventional or routine is an examiner that has only approved 2 applications out of 114 the last 12 months, as I am told by another poster on this website. Why even bother to approve those 2, and were the other 112 rejected people and legal counsel clearly mistaken by their inventions?

So while my peers have congratulated me on my accomplishment, I get rejected by a public servant that has not served one day in my respective field. As an aside, I was in front of important people at Healthcare.gov within 3 days (no kidding) after word of my accomplishment. Yet nobody with pony up the investment in a politically charges environment that awards contracts for reasons not so proper (kickbacks, etc) because protection of their investment has not been possible due to statements that are not factual, not truthful and not logical.

So if my examiner wants to be proud of himself for such an accomplishment of rejecting my application, it comes at the expense of hurting a lot of people with disabilities, their families and their caregivers (the state and federal governments who spend billions more per year for not solving this problem- independently proven fact).

You might want to add another category to this article: The Insubordinate Examiner- The examiner who fails to take direction from his own Director’s policies (policies that may be right or wrong) regarding s101 “practical application.” I for one would welcome turning the burden of proof on the infringer once I met my level of proof, regardless if the Director’s procedure has no force of law. S101 is an enabling statue, not a hide behind to achieve Master, Ideologue or Decider “club” status.

Anon

January 31, 2019 06:21 pmC,

That is a down right shocking view that you present. Helping an innovator obtain protection for the items that may separate his contribution from the prior art as determined by the government agent whose job it is to find that best prior art (and make sure all other government requirements are met)…

That’s like the “Evil Star Trek” mirror universe to the “Just Say No – Reject Reject Reject” universe that oh so many patent examiners (and bureaucratic flunkies hidden out of direct line of sight in the Office) still espouse.

Jeff

January 31, 2019 05:29 pm@C, yeah the type names were meant to be a bit tongue in cheek, and Master was to evoke an unbeatable martial arts master from an action movie. Though I don’t know that it is part the of the patent examiner’s job to help an applicant find patentable subject matter. Many examiners suggest amendments to get claims allowed, but I don’t think the MPEP or other USPTO requires that.

C

January 31, 2019 01:46 pmRespectfully, calling an examiner who grants almost no intellectual property rights a master is a serious misnomer. Finding the best prior art AND suggesting allowable amendments around it to provide protection is the goal. You sleep better when you know you’re helping people, rather than getting frustrated over some imagined encroachment on your pet subject matter.

The intent on both sides of the desk is to secure intellectual property and promote economic activity in the United States. In the same way that it is clear when an examination is not thorough, it is also clear when the originally filed claims were never intended to be narrow enough to warrant allowance.

It is all of our responsibilities to proceed to allowable claims in light of the best prior art as quickly as possible.

Jeff

January 31, 2019 11:33 am@David Stein, thanks, glad you like the post. I did intentionally choose examiners who were most representative of the type. I had someone else also suggest that I cluster all of the examiners to the different types with an indication of the art unit. I love that idea, and I’m planning on a follow up post with those details.

Anon

January 31, 2019 09:55 amThere is a fundamental error in the assumption that an appeal by the Office is a validation of the propriety of the position of the examiner, rather than merely an extension of an ideologue anti-patent view.

Overall though, I enjoyed the article and the analytical breakdown of what is only the first engagement in the battle for innovation protection.

Jianqing Wu

January 31, 2019 09:33 amFor years, I figured out that the final outcomes of patent examinations depend upon who examine applications. This is a big problem for the U.S. that depends upon intellectual properties. After the Alice decision and the start of using fashionable 101 rejection, invention merit is only a myth. Examinations applied imagination steps to reject claims. I see absurd actions one after another.

In such an examination culture, only patent attorneys can help inventors get patents by playing games, often at unpredictable costs. It is very bad to independent inventors or inventors who lack resources to fight. They often lose their inventions without getting patents at very high probabilities.

Congress needs to establish a new patent office that can shows that patents are granted on invention merits but not game-playing skills.

David Stein

January 31, 2019 09:09 amThis is great material, and those charts are excellent. I’ve certainly encountered all five of these examiners before.

However, I’m curious how closely the stats align with the actual examining corps. Surely the charts above are selected as an archetype of each examiner, which is fine. But is it possible to cluster examiners into these categories with good confidence? Or do most examiners fall somewhere in the middle, with only a small number featuring such distinctive stats as to fit into a category?

If categorization is possible, how does it line up with technology centers and art units? I suspect that chemistry-oriented TCs have a much higher rate of “negotiatior” and “decider” types. I also suspect that 36xx/37xx art units are overwhelmingly dominated by “masters”… but not because of their deftness at finding prior art, but because of 101, where the PTAB is not exactly a reliable source of relief.