“When a patent owner faces District Court invalidity-rates greater than 90% in some years and success rates as low as 9% to 14% to reach a judgment on the merits, is a license that’s priced to promote settlement a nefarious practice that takes advantage of the system or a reasonable business decision that takes into account risks that staggeringly disfavor patent owners?”

Wayne Evans

When you see a docket report with a patent lawsuit filed by a non-practicing entity (NPE), do you think it’s just another patent troll taking advantage of the system? Or would you be willing to consider that underlying every patent litigation is a human story of invention, which is the embodiment and manifestation of an innovator’s aspirations and sacrifices?

These human stories are too often marginalized in the patent troll debate. One such story is that of Wayne Evans. His life took him from the depths of poverty and loss to the struggles of being an entrepreneur raising a family and, ultimately, to late-in-life success as an inventor, innovator, and author.

Humble Beginnings

Evans was born into poverty in the heart of the Great Depression in 1935. His father left home when he was a child, leaving his mother to raise three children.

The seed for Evans’ lifelong passion was planted when he was five. He recalls wandering off one day looking for his sister. It didn’t take long for him to become helplessly lost. Hours seemed like an eternity before being found, as he repeatedly called out for his sister. Though traumatic, this experience fueled his dedication to help find people who were lost and in need of help.

Instability was a constant in Evans’ childhood. He lost his stepfather and eldest brother in World War II. It was difficult for Evans to process the loss. He harbored an anger towards life, feelings that masked a fear of dying alone.

Evans recalls finding relief from hard times losing himself in stories from his radio. His curiosity would get the better of him—how did his favorite stories come out of thin air from a wooden box? This enchantment planted the seeds for his lifelong quest to understand wireless technology and to help make the world a better place.

His curiosity pushed him to study electrical engineering at a local trade school in Indiana. He worked a midnight shift at a radio station to support himself. After graduation, Evans was of eligible draft age and enlisted in the military. Evans received training and became a military instructor in microwave communications, for which he was honored with the Outstanding Instructor Award in 1957. The military also honored him with the Outstanding Solider Award in 1959.

Evans at a military outpost on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, 1959.

Due in part to his technical expertise and resourcefulness, the military selected Evans to operate a defense communications outpost to monitor Soviet communications during the Cold War. In 1959, Evans was stationed in the coldest, most desolate military outpost on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, 500 miles north of any civilization. There, he was forced to confront his fears of dying alone when a hurricane struck the base. For three endless days, he endured threats of freezing and radiation poisoning. After the hurricane passed and military personnel rescued Evans, it took him four days to recover from hypothermia and shock.

One Hundred Dollars and a Roast Beef Dinner

When Evans returned to civilian life in his mid 20s, things turned around. He married Annie, the woman of his dreams, and earned an electrical engineering degree with honors from Purdue University.

After graduating in 1965, he accepted a job offer from RCA, the world’s leading consumer electronics company at the time. At RCA, Evans was part of a design team that pioneered innovations in consumer electronics. Evans invented and obtained more than 10 patents on a number of groundbreaking innovations, including the first use of an integrated circuit in a consumer device, the first transistor in a color TV receiver, and the first prototype of a wristwatch wireless communicator.

Evans was even featured in and photographed for Popular Science, for his contributions to the “television set of the future.” Popular Science, June 1970, pgs. 48-49. He delved into his passion for inventing and was elated to be on the cutting edge of consumer electronics. But the meager compensation he earned for his patents left him feeling empty. As an employee, he had to relinquish ownership in his inventions to his employer. In return, he received $100 per invention and a roast beef dinner.

After 13 years at RCA, Evans moved on to GE. His knack for inventing followed him but the opportunities to benefit from his inventions did not. His employer again reaped all ownership and profits from his inventions. After four years at GE, the recession of the 1980s befell the country. GE laid off employees, including Evans.

Evans at GE, 1980

Determined not to allow poverty to afflict his family, Evans embarked on a journey to create opportunities as an entrepreneur and business owner. But the road of entrepreneurship was a tough one. For the next 20 years, Evans would devote himself to developing location and safety technology, before the military allowed satellite use for civilians. From 1981 onwards, it was a constant cycle of scraping money together to start companies only to see them disappear, years without steady income and countless hours of manual labor, and endlessly negotiating collaborations that didn’t pan out.

Most taxing, though, was repeatedly going back to Annie over the years, explaining why he needed to close a business venture and start over.

Life as an Entrepreneur

As Evans cycled through numerous startup ventures, he took steps to innovate on his childhood dreams—to find better ways to implement location and safety technology in order to find those who were alone and in need of help.

In the 1980s, inspired by his daughter who was a nurse, and to help his elderly mother, Evans developed and deployed a location tracking system in an elder care facility to help identify and locate elderly patients in need of emergency care.

In the early 90s, Evans applied his location technology to vehicles. This time, he worked as a consultant with a South African telecommunications company to convert vehicle analog tracking systems from an analog cellular system to a digital one.

In 1998, Evans put his consulting travels and projects on hold when his mother needed support and came to live with him and his family in Atlanta. The time away from travel gave Evans an opportunity to delve into what he felt was missing with GPS technology, particularly in vehicle tracking.

Evans’ Personal Location Wristwatch Prototype (1969) next to smartwatch.

While working two consulting jobs, Evans began a two-year project to develop a new way to implement GPS tracking. Evans invested thousands of dollars, financed via credit cards, to start a laboratory in his basement. He conducted a costly trial-and-error process to set up his lab, buying and testing various equipment.

Though he wasn’t a programmer, Evans painstakingly developed something that did not yet exist—a latitudinal and longitudinal database with software to correlate GPS coordinates to street intersections.

After two years of trial and error and countless hours in his lab, he invented a telematics unit that he could take in his car and drive to a street crossing, and it would automatically recognize the intersection.

Though he didn’t know it at the time, this was the precursor to GPS location-based services that would 10 years later penetrate the worldwide market.

Inspired to develop technology to help people, Evans developed other innovations, such as emergency reporting systems, road hazard support for the disabled, and automatic collision notification systems.

Patent Problems

Evans believed he had developed enough to obtain patent protection on his GPS innovations. But patents were expensive. Evans took on heavy credit card debt setting up his lab and paying for his children’s college education.

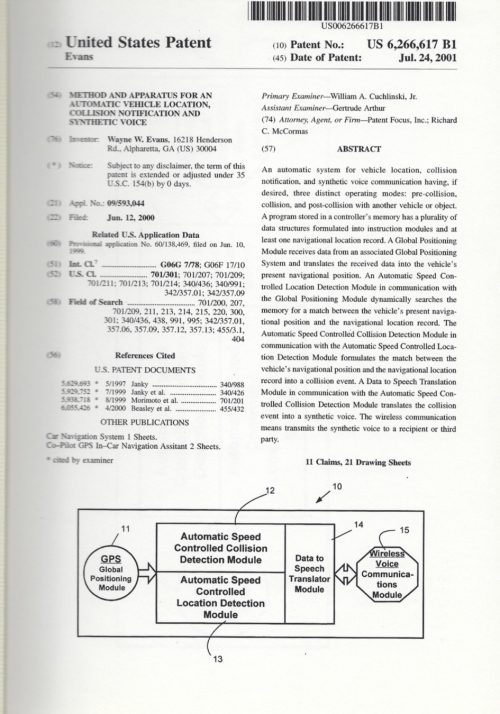

With the loving and unconditional support of his wife, Evans used their family’s retirement funds to hire a patent agent. Thanks to his agent accepting delayed payments, Evans filed and was issued a family of patents to protect his GPS inventions.

Evans was elated—in his late 60s he owned the intellectual property to his inventions for the first time in his life. His patents were the culmination of 20 years of researching better ways to implement GPS technology, testing theories in the lab, and investing in his dreams.

Evans was elated—in his late 60s he owned the intellectual property to his inventions for the first time in his life. His patents were the culmination of 20 years of researching better ways to implement GPS technology, testing theories in the lab, and investing in his dreams.

But Evans didn’t realize that he had another 10 years of hardship ahead. He still needed to promote his inventions and patents.

Evans was familiar with engineering, but patents were a new terrain. Now in his 60s, he had to learn how to operate in a world of patents. He was a fish out of water, trying to understand lengthy contracts and estimate reasonable rates and terms.

Evans couldn’t afford entry fees for trade shows where he could promote his prototype and patents, so he had to find other ways. He researched and found contacts to companies he believed could benefit from his GPS technology. He created marketing materials and scheduled calls and meetings to pitch his prototype and patents. But time and time again, each group would bow out and leads would go cold.

Evans next worked with IP promoters. He taught them about his inventions and illustrated their market applicability. But the IP promoters all wanted the same thing: upfront cash. It was cash Evans simply didn’t have. He was already in debt and drained his retirement funds to build the lab, design and test the prototype, and obtain his GPS patents.

It was the late 2000s and, now in his 70s, Evans’ health was declining. Emotional fatigue over a three-year long wills-and-trust litigation, stroke, and back injury limited Evans’ mobility and energy.

After 10 years of working to promote his patents, he felt the need to move on. After devoting decades, investing countless hours of labor, and taking on debt, he was at a dead end and fatigued. With a heavy heart, he had to explain to Annie why the investment in his lab and patents didn’t pan out, and why they again needed to move on.

Evans witnessed GPS technology blossom in the economy. He saw location-based services become a growing trend in the automotive industry. With sadness, Evans felt like he missed his opportunity.

The Collaboration

Though Evans moved on, his patents were publicly listed on the USPTO database. In early 2010, Evans received a cold call from the author of this article.

Though somewhat skeptical, Evans was happy to hear that our company believed his GPS patents were ahead of his time and had market applicability throughout the location-based services market. He was happier yet that we didn’t ask for upfront money. This began an eight-year working relationship and lifelong friendship.

We presented Evans with a list of companies we wanted to approach. Counterintuitively, we weren’t comfortable approaching operating companies in the location-based services space. We explained to Evans that patent laws were such that if we presented these companies with evidence of his patents’ value (i.e., claim charts that showed how Evans’ patent claims read on their products), that could expose Evans to a declaratory-judgement lawsuit. Without funding to defend a potential litigation, we couldn’t risk that exposure.

We researched the market and learned of other patent buyers, such as IP licensing groups that actively acquired patents. We created a 50+ page slide deck of marketing material illustrating the widespread market applicability of Evans’ patents. We presented market trends and how his patents map to in-unit telematics, personal navigation devices, smartphones with GPS applications, docking stations, and other technology areas.

We set up technical calls and developed an ongoing dialogue with a number of groups. We even extended our reach to European companies. But disappointingly, each group declined to make an offer. We realized IP licensing groups didn’t see the value we saw in Evans’ patents. After two years, we regretfully reported to Evans that our brokering efforts were fruitless.

The Last Resort: Lawsuits

Having exhausted every option to sell his GPS patents, we considered our final option—filing lawsuits to license his GPS patents. But lawsuits are expensive and Evans wanted no part of litigation due to his declining health and the wills-and-trust litigation that had left him physically and emotionally fatigued.

Despite the obstacles, we presented our plan to license his patents to companies in the locations-based services market. Though we’d been unsuccessful for two years, Evans put his faith in us and our plan. He assigned his patents to NovelPoint Tracking and we launched dozens of litigations to begin negotiations.

Despite the obstacles, we presented our plan to license his patents to companies in the locations-based services market. Though we’d been unsuccessful for two years, Evans put his faith in us and our plan. He assigned his patents to NovelPoint Tracking and we launched dozens of litigations to begin negotiations.

Litigation afforded us the opportunity to negotiate directly with companies. At the end of our five-year licensing campaign, Evans reaped the rewards of his then 30-year pursuit of GPS technology. More than 80 companies took a license to Evans’ GPS patents. In his 80s, Evans became a millionaire.

After a lifetime of working in industry, founding eight startups, and being the inventor on 18 patents, it was by taking the risk to finance his own patented inventions and filing lawsuits that Evans found his success.

With the money earned through patent licensing, Evans replenished his retirement funds, paid for much-needed healthcare for himself and his wife, and invested in his kids’ and grandkids’ businesses.

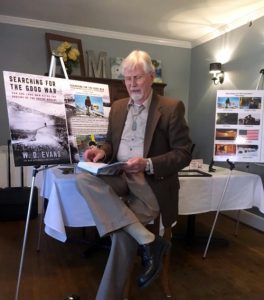

Today, Evans has newfound vibrancy. He is a motivational speaker, the author of six books and is working on six more.

The Backlash

Despite the success, Evans’ patent and our litigation efforts received harsh criticism. One critic nominated one of Evans’ patents for the “Stupid Patent of the Month.” The critic contended Evans’ patent “devolves into a wilderness of made-up words and technobabble . . .” and “includes fabricated phrases” that makes understanding its meaning an exercise in “cross-reference and guesswork.”

The critic continued: “Even worse, key terms in the claims . . . don’t even appear in the description of the purported invention, . . .” making it “very difficult, if not impossible, to understand what the claims mean and to guess how a court might interpret them.”

This critic noted none of NovelPoint Tracking’s litigations reached a decision on the merits of the claims and concluded that the patent was a “great example” of “how using fake terms can be used to obfuscate what the patent actually claims, and then used to claim infringement” for something other than the invention.

I’d like to respond to that. When Evans filed the patent applications on his GPS innovations, he didn’t use “fake terms” to “obfuscate what the patent actually claims.” He was thankful to work with a patent agent who accepted delayed payments and relied on him to draft the technical language of his patent applications, to protect the innovations he sacrificed to develop.

Evans never “gam[ed]” the system. When he used his family’s retirement funds to finance his patent filings, he believed that after spending two decades on research, financing his lab, and working late nights to develop his prototype, he made an advancement in GPS technology that was worth the sacrifice to patent.

When Evans developed his prototype that could convert latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates and automatically recognize street intersections, this was a breakthrough in location-based technology for which Evans should receive praise.

If the critic reads Evans’ patent and, contrary to foundational patent law principles, believes it’s limited to what’s described in the “Background of the Invention” regarding automatic location and collision notification, and is further unable to interpret patent claims that had been approved and issued by the USPTO, one must question whether that is a problem with Evans’ patent or the critic’s competency.

Regarding NovelPoint Tracking’s litigations, the critic surmised we were “gaming” the system by intentionally avoiding a decision on the merits and settling for “nuisance value.”

If you believe that, then consider this: when a patent owner faces District Court invalidity-rates greater than 90% in some years and success rates as low as 9% to 14% to reach a judgment on the merits, is a license that’s priced to promote settlement a nefarious practice that takes advantage of the system or a reasonable business decision that takes into account risks that staggeringly disfavor patent owners?

In the end, we licensed Evans’ patents in a manner that honored his wishes to avoid his involvement in litigation. I can’t fault the critic for her opinion, because she was unaware. I hope this article sheds light and facilitates greater understanding.

Evans’ GPS patents aren’t stupid. His 20 years of research to develop GPS technology wasn’t stupid. His sacrifice to delve into his retirement funds to finance his patents wasn’t stupid. And successfully licensing his patents as a last resort after 12 years of attempted IP promotion and brokering wasn’t an example of gaming the system.

It’s honorable. It’s a story worth telling. It’s a story of an American who believed in himself and his dreams and was willing to put it all on the line.

The next time you see a patent lawsuit listed on a docket report, I hope you remember this story.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

31 comments so far.

LazyCubicleMonkey

February 22, 2019 11:06 pmIt’s easy to focus on the plight of the solo inventor.

But how about the plight of a solo business owner that gets one of these infringement letters? Doesn’t actually matter if you’ve infringed or not, the cost of defending against such a claim can bankrupt them just the same.

In theory, what’s to stop a patent owner from sending these infringement letters to anyone? Even someone they know isn’t infringing? What’s the recourse of a solo business owner? Who’s looking out for their interest? And what can they do in such a case to avoid being out thousands of dollars, either from the forced licensing or the hiring of an expensive patent attorney?

Benny

February 19, 2019 02:44 pmMJG,

If your idea can be copied with a twist of a screw you can be pretty sure someone else will patent it, if they haven’t done so already. Also, you haven’t done a search if you haven’t looked at the Chinese patent database.

Mitchell Jay Goldstein

February 19, 2019 06:20 amWith the internet the way it is and data dating itself is the documentation of a patent really necessary if the idea can be copied. Is it worth the money to pay the price for patent. With the government or can I just state or make s Statement of Fact and publish it claiming it as my record of discovery and new idea . Won’t giving it a date stamp after a. Patent search make me the first just by that statement alone. Doesn’t the correspondence between inventors and manufacturers hold legally due to formal emails and such. My idea is new but with a twist of a screw it can be copied and I’m sure it will once I finish my prototype and build a few they will show up in a different variation even though there are none today

Wayne Evans

February 3, 2019 03:15 pmI thank each and every one of you for the spirited discussions about my patents.

In any case, it’s been quite a ride with my understanding wife for over 58 years of putting up with all my crazy ideas and inventions.

Thanks Annie and Great Job, Gau.

Perkins

February 3, 2019 11:55 amUntil Congress quits accepting bribes from, and instead reins in the multinational big data corporations, the U.S. will never again lead the world in innovation. Their attitude that Congress can’t possibly understand the technology and should let these corporations police themselves is one of the major reasons why the hard working middle class is quickly disappearing and being replaced with the hands out entitled class.

Dave Barcelou

February 2, 2019 01:32 pmAnon 24 – There’s no reasoning with the “we want everything FREE Bernie crowd”. They don’t miss the point, they’re not capable of critical thinking. Who’s John Galt?

Anon

February 2, 2019 11:43 amJusten,

You are missing the points here.

“And if in their mind, the patent actually covered gps that is being used today, then they’d be a fool not to jump on it. But they said pass.”

Just as you share that you made a business decision to pay licensing (rather than litigate) on something that you thought not proper, others make a business decision to NOT pay licensing on things that ARE deemed proper.

So while you admit (in passing) that Efficient Infringement exists, you then continue to post as if it did not.

And yes, there are “bad actors” out there, but the “Patent Tr011” boogeyman is an overblown scare tactic CREATED by Efficient Infringers for the sole benefit of Efficient Infringers.

Posts such as yours that give lip service, and then pretend this behavior does not exist does not portray the “Patent Tr011” narrative correctly, and instead plays right into the mantra of the Efficient Infringers.

That’s simply not helpful (and as can be seen with the relentless attacks on strong patent rights), that’s actually quite harmful.

Justen Hansen

February 2, 2019 08:35 amBenny, I agree.

Anon, Sure, it’s a problem, but that doesn’t mean everyone that turns down a license is an efficient infringer. There are still plenty of valid licencing going on and still plenty of frivolous lawsuits filed. I personally represented a company that chose to pay an exorbitant licensing fee on a patent we didn’t infringe because it was cheaper than litigation.

Gautham, that’s what I was trying to get at. They work on business decisions. And if in their mind, the patent actually covered gps that is being used today, then they’d be a fool not to jump on it. But they said pass.

Dave Barcelou

February 1, 2019 11:21 pmAnd Gene @8, as far as “[banks & credit unions in my case] not responding to ANY licensing inquiries — reasonable or otherwise [been there – had that done]. There [w]as a concerted refusal to deal with the inventor and patent owner [me]. When that happens the only recourse is to sue…” [then they pick up the phone].

And…”To the extent the term “patent troll” has any continued relevance it has…” [considerable relevance – twenty-five YEAR$ and > twenty-five MILLION to me]!

Dave Barcelou

February 1, 2019 11:10 pmFor those of you interested in someone who’s been painted in a “false light” as a “Patent Troll” and has sued for Defamation [the term is provably ‘true’ or ‘false’] using the Defendant’s own Definitions; “he doesn’t make anything”, or, “he purchased his patents from a 3rd-party, etc.” [both FALSE] and suffered significant damages as a result, should tune in at 10 am on ‘Valentine’s Day’, February 14th for a ‘Livestream” from NH Supreme Court at: https://www.courts.state.nh.us/videos/supreme/index.htm

Gautham Bodepudi

February 1, 2019 12:26 pmJusten,

I would like to respectfully question your presumptions from your previous comment:

“By your own admission, licensing groups didn’t see the value in the patents. These are people who know what gps is and how patents work and they didn’t see the value in it? It wasn’t until you sued people that it was worth something? Sounds like a classic patent troll to me . . .”

If a licensing group saw “value” in the patent, would the activity no longer be that of a “classic patent troll?” Why do the opinions of licensing groups set the bar on what constitutes a “classic patent troll?”

If its based on the presumption that licensing groups are the unquestioned experts on patent valuation, would you change your view if you learned many of those groups are no longer in business today?

Licensing groups make business decisions when it comes to patent acquisitions. Business decisions of licensing groups are particular to their respective businesses. Not all licensing groups are created equal.

Instead of basing your opinion of “patent value” on the business decisions of others, following Benny’s point above, I would suggest forming an opinion based on your own analysis.

Justen

February 1, 2019 11:37 amBenny, I agree.

Anon, sure, it’s a problem. But you can’t assume every company accused of infringing is one. There is no shortage of legitimate licenses taken daily, and there is no shortage of frivolous lawsuits being filed.

I personally represented a company that took a very expensive license on a patent we didn’t infringe because we didn’t want to pay for litigation.

Anon

February 1, 2019 06:41 amJusten,

Have you been paying attention to the activities of the Efficient Infringers?

Benny

February 1, 2019 06:26 amJusten,

Anyone with a hint of IP itelligence would first read the claims and ask a) are different methods currently in use and b) are the claims enforceable, given the difficulty in determining if a product infringes (the claims of the patent mentioned in the article are very specific )

Justen Hansen

January 31, 2019 10:46 pmGene,

I agree with your statement that people wouldn’t want to take a license, but the author said he was trying to sell the patents, not license them. Anyone with a hint of IP intelligence would be willing to at least make an offer on a patent that covered gps. Especially an IP licensing group.

Benny

January 30, 2019 02:10 pmGene,

Foor the record, I don’t work for a “mega-infringer”.

Gene Quinn

January 30, 2019 01:54 pmBenny-

If you figure out a different, non-infringing solution you don’t owe a license. But should you be laughing it up at conferences that you simply throw away EVERY letter you receive because the laws have become so one sided that you don’t need to pay for anything any more?

If we are honest, we all know we have heard attorneys from the mega-infringers practically giddy explaining their “circular filing” technique for handling patent owners. So, I find it quite disingenuous for them to cry about getting so many letters. Is it really that hard to throw away a letter? Is throwing away every letter you receive SO taxing? Asinine if you ask me.

SteveT

January 30, 2019 12:51 pm“Even worse, key terms in the claims . . . don’t even appear in the description of the purported invention”

This is the patent attorney dilemma — the more inventive the concepts in an invention, the more likely one has to either make-up words, or use existing words out of their normal context. To me, rather than a sign of ambiguousness, an inventor with a lexicon can often be a sign of a great innovative leap.

Anon

January 30, 2019 12:23 pmBenny,

As your views so often reflect the Efficient Infringer mantra, and you often confuse just what a patent (or patent application) IS — wanting an engineering document instead of a legal document — I have to take your reply here with a rather large grain of salt.

I other words, your plain words here may indeed ring true – as far as that goes – but may also not ring true to either this particular circumstance OR the more general and prevalent circumstances.

You do know just who created and propagated the entire “Patent Tr011” campaign, right? And why, right?

Benny

January 30, 2019 11:35 amGene at 8,

You suggest that “To the extent the term “patent troll” has any continued relevance it is for someone who uses judicial inefficiencies with a bad patent “. I disagree. I don’t think trolling has any relevance to whether a patent is “good” or “bad”. Trolling is trying to extort money from people who owe you nothing, i.e, entities who do not infringe your patent (which may well be novel and innovative, and owned by the inventor).

Pro Say

January 30, 2019 11:28 amYou’re welcome Gau. Many inventors wouldn’t be able to invent without the loving support of their spouses and family.

This ridiculous troll narrative (and 101 baloney) hurts far more people than just our inventors. Far more.

And O/T everyone — comments on the new pto eligibility guidance are up:

https://www.uspto.gov/patent/laws-and-regulations/comments-public/comments-2019-revised-subject-matter-eligibility

Disenfranchised Patent Owner

January 30, 2019 10:49 amHow did this guy avoid being gang-raped by the PTAB’s kangaroos, CAFC, etc.? The fact that one inventor somehow survived in the current anti-inventor climate is heart warming.

Benny

January 30, 2019 10:08 amGene,

In reference to this particular case, and reading the claims of the patent mentioned in the EFF blog, how would you go about proving infringement before sending a letter claiming intellectual property rights over a software application to which you probably have access only to the presentation layer? Do you think that requesting a license for IP without proof that the IP, specifically as laid down in the granted claims, is infringed, is honest practice?

I must add that I do not know if the patent owner had proof of infringement, but from my own experience I can tell you that I cannot prove infringement of our or our competitor’s software driven method claims without deep reverse engineering – something which was not mentioned in the article.

In now way do I intend to diminish the accomplishments of Mr Evans, but if I, a decade after his innovative work, figure out a different solution to the technical problem, then I don’t owe him a license.

Gene Quinn

January 30, 2019 09:47 amJusten-

I want to jump in here because you raise a very important red herring. The fact that people are not interested in licensing an invention is really quite meaningless. Once upon a time that would have been relevant, but anyone who is at all familiar with the industry well knows that attorneys for the mega-infringers will speak at conferences on panels and laugh… LAUGH… about not responding to ANY licensing inquiries — reasonable or otherwise. There has been a concerted refusal to deal with inventors and patent owners. Everyone knows that. Is is well documented and admitted by the mega-infringers. When that happens the only recourse is to sue.

Accepting a reasonable settlement in light of the risks does not make a patent troll. To the extent the term “patent troll” has any continued relevance it is for someone who uses judicial inefficiencies with a bad patent to extort a few thousand dollars. Even the Obama FTC explained that the term “patent troll” is misleading. So it is curious that you would find this story to be indicative of a “class patent troll” in your words.

Frankly, the patent trolls should be the tortfeasors who have engaged in the concerted refusal to deal with patent owners. They are the ones who created this problem, and propped up a patent troll narrative in order to defang patents generally. They have succeeded beyond their wildest dreams, and look at the industry they have created for themselves where very little that is software related can be patented. Even artificial intelligence and autonomous driving is moving overseas. That is NOT a success story. It is a story about America fumbling the ball.

Gautham Bodepudi

January 30, 2019 08:57 amPro Say,

Thank you for the kind words. I passed your comment on to Mr. Evans. His wife will appreciate your recognition. Thank you.

Justen Hansen

January 30, 2019 08:11 amBy your own admission, licensing groups didn’t see the value in the patents. These are people who know what gps is and how patents work and they didn’t see the value in it? It wasn’t until you sued people that it was worth something? Sounds like a classic patent troll to me, especially because Mr. Evans’ technologies, although commendable, never effectively contributed to what was finally used.

Using pathos to convince us that patent trolls earn their dues?

With that said, I’m glad Mr. Evans has a happy ending. Concerning Mr. Bodepudi, there’s a reason Model Rule 7.3 exists.

EG

January 30, 2019 08:05 amHey Curious,

I too knew that when the article mentioned “Stupid Patent of the Month” that it was authored by some idiot at the EFF who wouldn’t know what technology was if it hit them in the face. The EFF and their ilk are a scourge, a bunch of freeloaders who want everything for free. As this story told here shows, there’s no “free lunch” when it comes to innovation.

Benny

January 30, 2019 05:37 amSo…I looked up the “Stupid patent of the month” article.

My conclusions ?

1- It is not a stupid patent (unlike most of those featured in the EFF blog which are often embarrassingly stupid).

2- The patent attorney could have, and should have done a better job of writing the claims.

3- Proving infringement of the claims, as they are written, would be extremely difficult without access to the potential infringer’s source code. Potential infringers know that.

I would guess that some of those approached with a request to obtain a license took the approach “I didn’t do it, nobody saw me do it, you can’t prove anything”, while others may have looked at the patent and said “That’s not how our system works. Why do we need a license?” However, after a power point presentation titled “Discovery Process” by their outside counsel – who wouldn’t prefer to pay a license fee?

My guess – based on reading the claims, and technical knowledge of similar systems, is that this is not a black and white case. Without concrete evidence, (which I’m guessing the patent holder also lacks) , I would guess that a percentage of the licensees are not infringers.

Dave Barcelou

January 30, 2019 03:22 amThis is a great story which is probably worthy of a book to truly understand fully. Those of us who have similar story’s can empathize with the likes of Wayne Evans. H/T Gau Bodepudi for hanging with him and closing the deal with a happy ending!

Curious

January 29, 2019 09:38 pmSo … I looked up the writer of the “Stupid Patent of the Month.” Naturally, an article published by the known anti-patent organization, EFF. From her bio, “she worked as a Senior Staff attorney, at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, where she focused her work on patent policy.” She is now defending silicon valley corporations from patent infringement.

Anyway, what you have is an anti-patent organization putting out anti-patent propaganda — more than likely at the behest of one of its well-heeled benefactors that support EFF.

Surprise, surprise … the same firm that employs her also employs Mark Lemley (founding partner).

It is no surprise Mr. Evans was recipient of this attack. Mr. Evans probably approached somebody with enough clout at EFF to sick them on Mr. Evans.

I doubt the likes of Mark Lemley (and the author of the attack piece against Mr. Evans) ever met a patent that they thought was valid. I have nothing but contempt for their ilk. If they had their druthers, the entire patent system would get burned down — or at least limited to technology that existed in the 1800s. They are lick-spittlers of the internet oligopolies who think of little of appropriating the technologies of others.

Pro Say

January 29, 2019 08:08 pmThank you Gau and Wayne.

Another great story and example of a hard-working, well-deserving American inventor.

And God bless such a woman who would stand by her man through thick and thin — just as the Lord would have it.