In Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., the Supreme Court purported to clear up the long-standing confusion regarding potential copyright protection for the designs of useful articles. Specifically, the Copyright Act covers “pictorial, graphic and sculptural works,” and extends protection to the design of a useful article, but only to the extent that the design incorporate features “that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” (Section 101 – definition of “pictorial, graphic and sculptural works”) As I previously discussed in a post on IPWatchdog, courts had developed numerous indicia to help them determine the dividing line between applied art, which copyright appropriately protects, and industrial design, which is within the sole province of patents. (The Supreme Court May Give Product Designers Little to Cheer in Star Athletica, Sept. 19, 2016) Unfortunately, the resolution of product design cases often depended on the guideposts that the reviewing courts decided to adopt, which led to uncertainty in the field. The Supreme Court, in Star Athletica, intended to bring greater clarity and predictability for product designers by replacing the large set of tests with one standard. To this end, it held:

[A] feature incorporated into the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection only if the feature (1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and (2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic or sculptural work – either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression – if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated.

Subsequently, I published another piece with IPWatchdog that questioned whether the application of this test would merely raise a host of new questions, while leading courts down a slippery slope that might possibly increase the role that copyrights play in protecting product designs. (Does Star Athletica Raise More Questions Than It Answers?, April 13, 2017). Indeed, I hypothesized that by using the Supreme Court’s approach, one could theoretically protect the original external shape of an LED light bulb cover with copyrights.

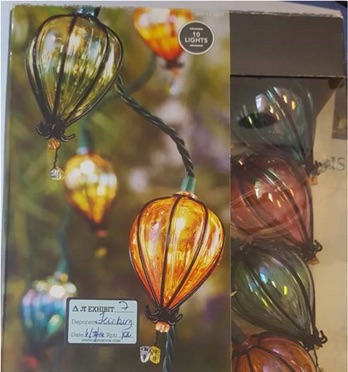

Ironically, a New York district court judge, in Jetmax Ltd. v. Big Lots, Inc., recently used the Supreme Court’s Star Athletica standard to resolve whether the light bulb covers on a string of ornamental lights are copyrightable subject matter. The plaintiff alleged that it owns the copyright in its Tear Drop Light Set, which has individual lighting elements encased with teardrop-shaped plastic iridescent covers. Each cover is surrounded by a wire frame and includes a dangling plastic stone, so that it has the appearance, at least to this author, of a hot air balloon. (see Figure 1). Big Lots sells a decorative string light set that looks very similar, although there are some subtle differences; the bulb covers, for instance, do not have an iridescent finish, and they omit the dangling stones. (see Figure 2)

Jetmax sued for copyright infringement, and Big Lots filed for summary judgment, claiming that the designs of the light bulbs are not copyrightable subject matter because they cannot exist independently from the utilitarian aspects of the light string.

Based on the Supreme Court’s decision in Star Athletica, the judge denied Big Lots’ motion to dismiss, ruling that the light bulb covers could indeed be imagined separately from the useful article and so qualified as sculptural works under the Copyright Act. In reaching this conclusion, the judge determined that the utilitarian aspects of the light set were the interior lighting elements and other components that cause the strand to light a room. She claimed that it did not matter that the covers serve a utilitarian function within the string set, such as by reducing glare from the bulbs. Indeed, the Supreme Court did note that an artistic feature that would be eligible for copyright protection on its own cannot lose that protection simply because it was first created as a feature of the design of a useful article, even if it makes the article more useful. So the judge is on firm footing, in this regard, based on Star Athletica.

My intuition is that the judge came to the correct conclusion, but that the Supreme Court test ultimately did little to guide her thinking. As I mentioned in my previous IPWatchdog article, determining the contours of the useful article is a metaphysical exercise that likely will require other “tests” to resolve. Why, for instance, does the useful article not consist of the lighting elements, sockets, wires and covers, which the judge admits also serve important utilitarian functions? What factors caused her to draw the line so that the covers were not included within her concept of the useful article? My guess is that it came down to the fact that in her view, “The primary purpose of the cover is artistic; once the covers are removed, the remainder is a functioning but unadorned light string.” Of course, the “primary purpose test” happens to be one of the benchmarks that the Supreme Court meant to replace with its new standard. But these tests were devised over the years to separate art from utility in a wide variety of contexts, and I don’t believe that the Supreme Court’s new standard will ultimately serve as an effective substitute for them. If anything, the decision in Jetmax proves the point.

Although the court ruled that the light bulb covers are copyrightable subject matter as sculptural works, Jetmax has not yet won the case. Big Lots, for instance, may be able to prove at trial that the designs are not original. Also, Big Lots alleges that Jetmax does not own the copyright in the light set. Thus, as is so frequently the situation when addressing product designs, the strategic question here was whether the defendant could put a quick end to the case through summary judgment. Big Lots failed to convince the district court judge on this score, but it still remains to be seen how the litigation will ultimately be resolved.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.