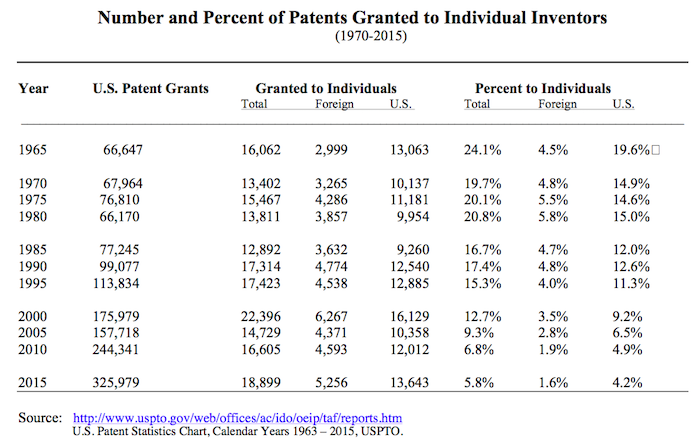

For decades, individual inventors were granted 25 percent or more of all U.S. patents. This creativity was the foundation of dozens of new industries, thousands of new companies and millions of new jobs.

For decades, individual inventors were granted 25 percent or more of all U.S. patents. This creativity was the foundation of dozens of new industries, thousands of new companies and millions of new jobs.

Yet beginning in the early 1980s, their portion of granted patents begin to drop like a rock in free fall. By 2015, individual inventors received only 5.8 percent.

A decline so great and so fast has profound consequences and is not an accident or fluke.

A useful place to begin the examination of this decline is a 1998 interview of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates who was asked, “Mr. Gates, what’s your biggest worry? What’s your business nightmare?”

Gates paused a bit and then said, “I’ll tell you what I worry about. I worry about some guy in a garage inventing something, a new technology, I have never thought about.”

Prescient and ironic? Certainly, because at that very moment two guys named Larry Page and Sergey Brin were working in a Menlo Park “garage” inventing Google, which quickly became one of Microsoft’s worst business nightmares.

What Gates really feared was described by economist Joseph Schumpeter as “the gale of creative destruction” – a process of economic mutation that “incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.” Inventors and their inventions most often drive this gale – a process that makes them very dangerous to established ventures such as Microsoft and Apple.

In 1776, Adam Smith described such ventures’ almost baked-in genetic reaction to this Schumpeterian gale: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

In a 1994 interview now on YouTube, a young, cocky, newly rich Steve Jobs succinctly described in the language of our times how he and Apple dealt with this innovation-driven gale. “Good artists copy,” he said, “Great artists steal. We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.”

Although Jobs created in Apple what is now the world’s most valuable company and Gates became the world’s richest person, their fears of this creative destruction pervade global commerce. Also common is the willingness of many established ventures to confront the challenge by stealing others’ creations.

To paraphrase Jane Austen “It is a truth universally acknowledged that an established venture in possession of a good market share, must be in want of its competitors’ inventions.”

To facilitate acquiring competitors’ inventions, established ventures in the United States had to contend with competitors’ access to the very same patent rights that abetted the ventures’ own economic success – powerful rights that operate to induce inventors to innovate, and investors to invest. It’s been said that the patents of Alexander Bell, the true father of modern telecommunications, provided him with a “Gibraltar of security.” Established ventures in quest of competitors’ inventions, had, in effect, to conduct a raid on Gibraltar and assume the attendant risks.

The U.S. patent system – this Gibraltar of security – originally provided three basic layers of defenses.

First, the Constitution secures via a patent the inventor’s property rights. Note that the word in Article I, Section 8 is “secure” – the inventor already owns his invention from the time of its creation. The U.S. Government’s grant of a patent provides this security and prior to 1980 only an Article III Federal Court and a jury could declare any patent claim invalid.

This security exists in the form of a Social Contract between the inventor and the Government as representative of the public. Per the contract, the inventor pays the steep price of disclosing into the public domain detailed information about his invention, including the best mode to replicate it. In exchange, the Government gives the inventor a patent entitling him to exclusive us of the invention for a set period – a right enforceable in an Article III Federal court.

Both parties to this Social Contract won: By expanding knowledge, the U.S. sought progress. By sharing knowledge, the inventor got legal protections and several years of exclusive use. This contract is a principal reason why the U.S. leads the world in innovations.

The patent system’s second layer of defense was that the patent was issued to the first and true inventor. This gave the inventor time to perfect his innovation. Unlike in Europe, which has a first-to-file patent system, there was no need in the United States to rush to the Patent Office and risk filing a premature application.

Third, the Patent Office was prohibited from disclosing to the public the details of a patent application until a patent was granted. Rejected applications were destroyed – thereby allowing the inventor to practice his creation as a trade secret, or improve it and try again for a patent.

Not surprisingly, weakening this Gibraltar of patent security legislatively, administratively and judicially has been a top political goal of established ventures for most of the past half century. They have spent literally hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars lobbying Congress and Presidents and trying to shape the public view.

The principal of these proposed changes was defined in three high level national commissions that were convened between the mid-1960s and 1992. President Lyndon Johnson’s Commission on the Patent System issued its report in 1967.

President Reagan’s Intellectual Property Committee issued its report in 1988.

The Advisory Committee on Patent Law Reform, a blue ribbon group created in 1990 by President George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of Commerce Robert Mosbacher, issued its final report in 1992.

The recommendations in these three major reports were subsequently echoed in dozens of other studies by other prestigious institutions including the Federal Trade Commission, The National Academy of Science and the National Research Committee.

These Commissions and their recommendations had three common and distinctive characteristics. First, the membership of each Commission consisted almost entirely of (a) executives from major corporations such as IBM, Dow, Monsanto, Hewlett Packard, Procter and Gamble, and 3M – companies who had much to lose from “a guy in a garage”; (b) patent lawyers from the major national law firms that represented these and like corporations; and (c) academics from leading Universities whose research is heavily sponsored by these corporations.

Second, none these Commissions had a single member who was an independent inventor, or someone from a small business entity (500 or fewer employees) or a venture capital investor. Put into perspective when these Commissions were created, individual inventors and small entity companies received almost 30 percent of all U.S. patents granted annually. Yet, they were perceived and treated as a “guy in the garage” threat, which they were, of course. But they were they were given no seat at the table where patent policy was made.

Third, as if by design, the core recommendations made by each of these Commissions significantly weaken patent protections for independent inventors and small businesses in three basic ways.

Each report recommended (1) creating an administrative process inside the Patent Office that could cancel any claim in an issued patent which was a radical shift away from having such decisions made by a jury in an Article III Court; (2) shifting the grant of a U.S. patent from first-to-invent to first-to-file; and (3) requiring the Patent Office to reveal the details of a patent application at some early date, even if a patent were not yet granted.

Over time, Congress adopted every one of these recommendations. On December 12, 1980, public law 96-517 allowed the Patent Office to administratively cancel an issued patent in whole or part. PTO’s administrative powers were expanded in 2002, 2009, and again in 2012.

Taken together, these revisions have reduced the U.S. patent system’s “Gibraltar of security” to a virtual sieve for a crucial and vibrant category of American innovation.

The nation’s patent law now allows any person from any place the right to administratively challenge at the Patent Office any claim in any U.S. patent for the life of that patent. And the challenge can be made anonymously.

The Patent Office regulations state that “any person” may be a corporate or governmental entity as well as an individual. “Any person includes patentees, licensees, reexamination requesters, real parties in interest to the patent owner or requester, persons without a real interest, and persons acting for real parties in interest without a need to identify the real party of interest.”

Moreover, even if a patent claim is found valid in one challenge, another “any person” can challenge it again and another person yet again. Thus, wave attacks are now commonly used to invalidate or suppress the use of patents. Many investors refuse to license or invest in a technology while the patent’s validity is being challenged.

Worse for inventors, the American Invents Act sharply limits inventors’ rights to challenge PTO’s administrative decisions in the Article III courts, which alone afford patent owners the full range of Constitutional procedural protections.

The Patent Office’s internal administrative panel, named the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), has enabled virtually all commercially viable patents to be challenged for validity. This is proving to be the means by which well-funded established ventures repeatedly breach the “Gibraltar of security” that patents previously provided to inventors.

In 2014, a prescient former Federal Circuit Chief Judge named Randall Rader called these Administrative Panels “death squads killing property rights.” Patent Office statistics confirm his assertion.

In the 56 months between when PTAB went operational in September 2012 and May 2017, PTAB panels decided 1,601 challenges to issued patents. Of these, 65 percent had all claims cancelled. Put into context, the first administrative cancellation process created by the Patent Office in 1981 (Ex Parte Reviews) cancelled only 12 percent of the almost 11,000 patents in cases they decided in the 35 years between July 1981 and September 2016.

In another step that further weakens inventor rights, Congress enacted legislation (1999) that requires the Patent Office to publish the inventor’s full patent application, including all details, 18 months after the earliest filing date of the application. While the applications and inventor’s secrets are made public at 18 months, the average time required to process a patent application is almost 24 months. And if a patent is denied, which happens to about one out of three applications, the inventor’s technology goes into the public domain available to anyone, anywhere for free.

The whole of the research program of many predatory companies and governments is to have their engineers study these published patent applications so they can race to market before the inventor can.

A telling measure of this harm is the extraordinary decline in the number of U.S. patents sought and granted to individual inventors during the period of these three changes in U.S. patent policy and law.

In the 1960s and 1970s, individual inventors were granted almost 20 to 25 percent of all U.S. patents. But as the U.S. permitted administration cancellation of patents outside of an Article III court, required full and early disclosure of unprotected patent applications, and shifted to a first to file priority system, a growing portion of individual inventors either stopped inventing or stop seeking patent protections.

The numbers are stark. As recently as 1990, individual inventors were granted 17 percent of all patents. By 2000, they received 12 percent and only 6.8 percent in 2010. In 2015, individual inventors were granted only 5.8 percent of all patents.

In sum, if there is any example of a nation squandering its technological seed corn, this systematic weakening of U.S. patent protections for some “guy in the garage” is it. The great irony is that most of the people behind the screen in all this got their start in that same “garage.” They know this all too well, which is why they’re relieved to see the garage all but Closed for Business.

UPDATED Sunday 11:21pm PT to fix a typographical error in the penultimate paragraph.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

30 comments so far.

dh

September 28, 2017 01:33 pmThe Office of Patent Application Processing is given wide-ranging freedom in the primary classification of your patent. The rules regarding primary classification by staff in this office are remarkably permissive.

According to the USPTO (Examiners Handbook):

“The disclosures of patents are usually multi¬faceted, and such disclosures are susceptible to varied analyses.”

In addition, there is zero accountability as to who, in fact, was responsible for classifying you application and assigning its specific Group Art Unit (GAU). No one will sign off the classification process for your patent application.

Patent professionals, who fret about a “star chamber” at the USPTO, where administrators are provided positive means for influencing prosecution, appear to be largely oblivious to the fact that there is already a far more insidious and unaccountable mechanism that is currently baked into the system.

Patent applications can, and, in fact, are, sent to GAU’s based purely on claimed matter present only in a single dependent claim, thereby ignoring the primary invention of the claims. You can attempt to petition such behavior, but reading the guidelines will inform you that you have little legal leverage in this open-ended process.

While there is already a significant difference between allowance rate of GAU’s in similar classifications, the ability for an untraceable individual to assign your patent application to GAU’s corresponding to matter in a dependent claim allows for an un-named USPTO staff to have great latitude in choosing between sending your patent application to a GAU with an allowance rate of 80% versus a GAU with an allowance rate of 25%, with the added obstruction by an examiner not experienced in the class of the primary invention sought.

The utter absence of accountability in the USPTO in this primary classification process, with the vast discrepancies in GAU-to-GAU character and allowance rates (e.g., see “uspto-art-units-with-the-highest-and-lowest-allowance-rates” on this site) is a giant “welcome mat” for impropriety and collusion, and should be regarded as a giant red flag.

Anon

September 25, 2017 05:53 pmYour tales of woe Mr. Heller do not accord with either the law, my points on the law, or your lack of responding to points in particular conversations.

All this is IS you kicking up dust.

I am not impressed.

Edward Heller

September 25, 2017 05:35 pmanon, let me tell you of the agonies I have had trying to enforce claims where the patent attorney used functional names/expressions for structure disclosed in the spec. Obviously, the patent attorney was trying for broadness, but what he ended up doing was all but sinking the ship as he had to add limitation after limitation, argument after argument to distinguish the prior art that the broader expression nominally encompassed. In the end, we had to prove every added limitation, address every disclaimer, and it cost us tens of millions in litigation costs and lost damages. All of this was unnecessary as every single infringing device had the structure disclosed in the specification.

This is just one tale. I can tell many.

When I see an attorney using functional language to describe simple structure I almost get physically ill. It is so, so unwise.

Anon

September 25, 2017 09:37 am…and yet another thread Mr. Heller, in which you disappear from the conversation when pressed on a particular point that shows the infirmity to your larger viewpoints.

Anon

September 22, 2017 11:43 pm“anon, what I would like is clear and definite claims that particularly point out the invention within their boundaries.”

You do not know what that means, Mr. Heller.

You may think that you do, but your continual crusades against software, business methods, and words sounding in function (the perpetual attempt to have you explain the difference between PURE functional claiming and the “other blog’s” Prof. Crouch’s coined term of “vast middle ground” – among MANY other conversations that you always seem to abandon instead of conceding points put to you tells a VERY different story.

These words you use here: clear and definite claims that particularly point out the invention within their boundaries simply do NOT accord with your many, many, many posts.

dh

September 22, 2017 03:34 pmIt’s really quite simple.

There are GAU’s that are ordained as “easy” and there are GAU’s handling the same art classifications ordained as “hatchet men” who will obstruct ANY constructive progress, to a sordidly comic degree. This reality has been established in multiple forums, and can be verified in the published file wrappers of almost identical art (but in different GAUs)

Your application will be sent to one or the other of these opposite GAU’s dependent upon a, in fact, hidden persona (good luck finding out who that is!) who decides which one one of these GAU’s your application goes to – and they can (and do) choose the “classification” (and GAU) based upon only peripheral matter contained in one dependent claim of your as-filed application , as is convenient (cute. huh?).

The fix is in – and the collusionary forces aren’t even discrete about it now. Your quibbling over laws means little if no one enforces it.

Edward Heller

September 21, 2017 02:01 pmanon, what I would like is clear and definite claims that particularly point out the invention within their boundaries.

If you want the same, just say so, and we are largely on the same page.

dh

September 21, 2017 01:02 pmAIA pretended to “fix” what wasn’t broken, and accomplished the opposite of what it pretended to do – a trojan horse. It was a gift to the entrenched interests, and it aggravated the existing problem. The existing problem with poor prosecution was NOT the MPEP laws governing prosecution, but the poorly trained and unaccountable staff, who are not held accountable to follow those laws. REMOVE the AIA, and the drunken language of KSR; and, instead execute a system of better training, and ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS, and the USPTO system would function far more in line with its stated mission. As it stands, the trend is toward the opposite, and no accountability to the written law, which as stated by others, is not by accident.

Anon

September 21, 2017 08:18 amMr. Heller,

I am well aware of “what bothers you” and it has nothing to do with what you are stating here.

You have an agenda.

That much is beyond clear. This “112(f)” hobby horse of yours simply does not accord with the law as written by Congress in the Act of 1952. We have had this discussion many times, and I have even (painstakingly) walked you through comments by Federico showing that Congress fully intended to unfetter language sounding in function for combination claims (and yes, your “point of novelty” comments are outside of what the law actually is).

Further, I have asked you to explain (but receive NO answer from you) the difference between claims of pure function versus claims that merely have elements sounding in functional language. At that “other blog,” Prof. Crouch coined the phrase “Vast Middle Ground.” You constantly act as if that phrase has no meaning, when that phrase is critical to understand for our very point of contention.***

I recognize that you long ago lost a battle over 112(f) – you have NEVER recovered from that loss. You have YET to learn your lesson from that loss.

Until you are willing to not only recognize these weaknesses of yours, but also give the points full credit in our discussions, you will – inevitably and oh so typically – abandon the dialogue when these points come to bear.

How many times do we have to ride this very same Merry Go Round?

Come join me in an inte11ectually honest conversation – about the law as it is actually written, what it actually means, and why practitioners do what they do.

***another tangential point here on claim form, and the use of elements sounding in function (and NOT claims being purely functional) is the past stated desire of yours for the Jepson claim format. A format that has also recently received attention on that “other blog” and that currently (apparently) is used in less than a tenth of a percent of claims. Does this not indicate to you that your views on claim formats is simply not in accord with the rest of the US practitioners?

Not to be rude, but I wish that you would “wake up” and recognize your own limitations. What you crusade against is basic practice, basic practice that has evolved directly in relation to the Act of 1952.

Edward Heller

September 21, 2017 07:28 amanon, what really bothers me is that you deny there is a problem when there is a problem. The problem is caused in large measure by 112(f) which allows functional claims that appear to have very broad coverage but which are construed narrowly in court. Clients who do not know much about patent law may be fooled by the apparent breadth of the claim, invest heavily in businesses or licensing programs that depend upon the apparent protection, only to have the rug pulled out.

Accused infringers have two choices, seek a narrow construction to avoid infringement, or broad to invalidate the patent. With IPR, they can seek a broad construction in the PTO and a narrow in court.

Thus the patent owner is really not served well by apparently broad claims that are unenforceable at the breadth they claim. It would be better for all to have the claims cover exactly what they say they cover with no ambiguity at all.

dh

September 21, 2017 04:02 amHowever broad its claims, a “bad patent” is a weak patent, typically by virtue of weak search; and, if it is actually worth something (most are not), it can be re-examined in light of the new evidence.

The corporate forces to weaken the independent inventor are relying on the public and the congress to be completely ignorant of this process.

John Wu

September 20, 2017 12:58 pmThis article helps me a lot. The author mentions following two reports:

“President Reagan’s Intellectual Property Committee issued its report in 1988.”

“The Advisory Committee on Patent Law Reform, a blue ribbon group created in 1990 by President George H.W. Bush’s Secretary of Commerce Robert Mosbacher, issued its final report in 1992.

Anyone could give me links for finding those two Reports?

Thanks.

Anon

September 20, 2017 08:16 am“anon, you deny something that has been well known for 400 years. Inventors/applicants seek the broadest claims possible regardless of the scope of invention”

Mr. Heller, you supply a classic strawman and mischaracterize my position all at once.

NEVER have I indicated that the broadest possible claims will NOT be sought.

However – and it is NOT a coincidence, all of the “parade of horribles”: cases that you then cite are PRE-1952.

You STILL refuse to give full faith and credit to what Congress did (and please, let’s not descend to your favorite scapegoat of Judge Rich).

You, who so seems to enjoy history, take a rather strange ABSENCE from the actual history in order to pursue your agenda.

Do not attempt to inject your hobby horse in dealing with a different problem of the AIA.

You have no credibility in such an attempt.

Edward Heller

September 19, 2017 04:46 pmanon, you deny something that has been well known for 400 years. Inventors/applicants seek the broadest claims possible regardless of the scope of invention. This lead to public backlash in England in the late years of Elizabeth where she had to revoke scores of her patents. Morse had his claim 8. The there was Holland Furniture Co. v. Perkins Glue Co., 277 U.S. 245 (1928); Gen. Electric Co. v. Wabash Co., 304 U.S. 364 (1938); United Carbon Co. v. Binney & Smith Co., 317 U.S. 228 (1942); Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co. v. Walker, 329 U.S. 1, 67 S. Ct. 6, 91 L. Ed. 3 (1946).

Congress was told that bad patents are those with vague or over-broad claims the allow the patentee to construe his patent to read on the independent inventions of others. That is exactly the problem the Supreme Court identified in all of the above cases. Even if there is a rule of construction that construed a functional claim to cover only corresponding structure, etc., the apparent breadth of the claims remain a problem identified by the court.

Congress has been told that the problem remains, and why not? The problem has been with us for 400 years given the nature of attorneys who are only “looking out for their clients.” I say we will have a lot more credibility with Congress if we acknowledge that there is a problem rather than to deny it in the face of history and human nature. We need to redirect Congress away from post grant proceedings as a fix the problem of bad patents because the patent system needs reliable patents as a fundamental first principle, and patents are not reliable if they can be revoked at any moment.

Night Writer

September 19, 2017 12:38 pm@9 Anon: I agree about Ed the Ned.

Ed is friends with R. Stern the author of the center of evil of the patent world, Benson. I think Ed gets work from the Stern stream and needs to maintain his anti-information processing rhetoric to keep the work.

Person

September 19, 2017 11:08 amIn addition to the three ways described by the author, the positions of independent inventors and small businesses were also weakened by the introduction of maintenance fees in 1980. The grant of a patent no longer assured that it would remain in effect for 17 years unless fees were paid at the end of 4, 8, and 12 years after issue . After paying filing fees, issue fees, legal fees and possibly other PTO fees to obtain a patent, inventors were now faced with additional costs for the patent to remain in effect. For an individual inventor, these fees were another cost barrier that could more easily be met by large entities.

Anon

September 19, 2017 08:05 amBenny,

Can you flesh out your comment a bit more? It (almost) appears to be a complement, but since there is so little there on a substantive level (you do not address any of the items that Mr. Heller and I are “sparring” on), it is entirely unclear what your point is.

Benny

September 19, 2017 01:55 amEdward Heller,

You have to hand it to Anon. He takes criticism to the next level. I can almost believe you are sparring buddies since middle school.

Joan Maginnis

September 18, 2017 02:27 pmGentlemen! Can’t we all just get along?

Benny

September 18, 2017 12:46 pmChris,

Engineers search worldwide prior art, and not patent literature, when looking for cutting edge technology. They don’t rely on patent applications, both because they are 18 months out of date and because patent attorneys are useless when it comes to technical writing. I am assuming you have little experience of real world engineering, judging by your comment.

Anon

September 18, 2017 11:33 am“Anon, you have to understand that I know exactly what I am talking about because I have been on the other side of this issue. ”

To the contrary, Mr. Heller, I would posit that you have NOT learned your lessons from being on that “other side”: and in fact you STILL do not know what you are talking about.

With you, I am very much on guard against “friendly fire” BECAUSE I also am very much aware of your anti-software and anti-business method mantras.

Yours is typically an interesting discussion (as far as you may permit the discussion to unfold), as you DO have some pro-patent views, albeit you do not truly integrate those views when it comes to applying a consistent “world view” of innovation. You appear to be far too deeply ingrained in a “hardware-centric” view of innovation and you do not seem to grasp that soft WARE is every bit as patent eligible as any other of the WARES that exist in the computing arts.

Chris Gallagher

September 18, 2017 11:22 amBenny…. Think of it this way. Searching through worldwide prior art is a lot more labor intensive than perusing PTO application disclosures months before they result in patents or rejections where the trade secret route remains viable.

Edward Heller

September 18, 2017 09:48 amAnon, you have to understand that I know exactly what I am talking about because I have been on the other side of this issue. You know I was a patent counsel were very large company and I lead the struggle against so-called “form factor” patents. You should be happy that I have to some degree “switched” sides in this argument because I have “looked at life from both sides now.”

Ternary

September 18, 2017 09:43 amBenny. Many inventions that are deemed to be “obvious” by the USPTO are not obvious at all. These inventions did not exist publicly prior to publication. The artificial construct of the “person of ordinary skill” combining known art into the claimed invention is often not credible. In many cases the PHOSITA being confronted with prior art but not with the problem of the patent application would be unable to come up with the claimed invention. The crux of obviousness rejections is that the invention actually does not exist in the public domain, but only its constituting components. It is remarkable that many inventions are published in peer-reviewed articles and disclose novel aspects but are considered obvious by the USPTO.

Furthermore, rejections over 101 Alice as being abstract have nothing to do with inventions being in the public domain prior to application for patent.

Anon

September 18, 2017 09:33 amI see the old saw of “blame the applicant” crop up as a suggested “root cause” of “bad patents.”

Quite frankly, this is BS.

Bad examination just does not have the nexus that Mr. Heller dreams to be there.

This is nothing more than Mr. Heller’s hobby horse being led around the track.

Again.

Edward Heller

September 18, 2017 09:20 amThere is little doubt that weakening the patent system, or better, making it so expensive to actually obtain and enforce patents, allows entrenched monopolies to effectively ignore the patent system. Because big companies iterate as opposed to innovate, technological progress slows.

It is true that most, if not all, American revolutionary inventions spawned companies like Western Union, American Bell Telephone, General Electric, Aviation, integrated circuits, the Internet, computers. If one looks at the history of these companies, big money made investments in them at critical early stages because their investments were protected by the patent system.

We all have to keep this big picture in mind when we discuss things like “bad patents.” Assuredly, if the PTO is systematically issuing patents that are not properly searched because of vague and indefinite language in claims, the solution would seem to be to insist that the PTO and the courts require the use of definite language. Further, if the PTO is systematically issuing patents with broad, functional coverage far beyond the scope of the invention disclosed, the solution would seem to require that the PTO and the courts crack down on the use of functional language to claim an invention.

In the recent post by Russell Slifer, he described that Congress was motivated to create IPRs precisely because of these so-called bad patents that were abused because they could be abused. But the remedy they chose, to make the enforcement of patents virtually impossible except for the very well healed, has obvious collateral damage far beyond the problem of bad patents. Congress has to rethink what they have done and focus on the problem of bad patents by focusing on why they are bad in the first place. But certainly, they should reverse course completely on undermining the reliability and enforceability of patents once they are issued. They become the property of their owners, and they should never be haled back into the patent office for any reason.

Benny

September 18, 2017 08:42 am“… And if a patent is denied, which happens to about one out of three applications, the inventor’s technology goes into the public domain…”

That sentence makes little sense to me. A patent is denied (usually) precisely because the technology disclosed was already in the public domain at the time the application was filed.

Night Writer

September 18, 2017 05:33 amA graph would be good with normalized numbers for inflation adjusted billions of dollars of GDP for technology with foreign filings removed.

Reality: the number of patents has dropped over the 30 years considering how much large the tech sector has become.

Jim Nelms

September 18, 2017 01:08 amIts american greed at governmemt level together with all the old boy’s at corpoate level. Why don’t inventors file outside USA first? Any reason why not? The government does not want to look after its people but only cares for big businesses!

Jack Frazier

September 17, 2017 08:07 pmBill Gates famously said “some guy in a garage ,,,,:.