“Without a limited exclusive right in a patent, there is simply no incentive to perform risky and expensive research because anyone can steal the invention with impunity.”

Editorial Note: This article is a follow-up to Economic Trends and Productivity Growth Decline in America.

Editorial Note: This article is a follow-up to Economic Trends and Productivity Growth Decline in America.

—–

An unusual share of American prosperity can be traced to the U.S. patent system that originates in the intellectual property clause of the constitution. Congress established patent laws in 1790, 1793, 1800, 1836, 1952, 1999 and 2011. The 1836 Patent Act did not require modification for over a hundred years, while the 1952 Patent Act incorporated numerous Supreme Court decisions. In historical retrospect, the American Inventor’s Protection Act of 1999 represented the apex of the U.S. patent system.

With the election of President Bush in 2000, the balance of power in patent law shifted dramatically to the large institutions that were targets of patent infringement lawsuits.[1] In 2003, technology incumbents influenced an FTC report to recommend changes to patent law and, in 2006, the Supreme Court changed the standards of eligibility for an injunction, which essentially transformed patent law from a set of property rules to liability rules.[2] Numerous additional judicial decisions from 2006 to 2016 degraded the power of patent holders to maintain a limited exclusive right to their innovations. In 2011, the America Invents Act completed a transformation in American patent law that shifted power away from patent holders and towards the large technology companies. In a fifteen year period, patent law fundamentally disintegrated.

What exactly happened in the fifteen years from 2001 to 2016? Why did Congress and the courts so fundamentally change a patent system that provided the basis for a prosperous economy? How did these changes manifest in patent law in order to alter the patent system to shift rights away from patent holders? What are the consequences of these changes?

The Connection of a Strong U.S. Patent System and Economic Progress

The U.S. constitution embeds exclusive rights in a patent. Though patent laws originated in 1624 in Britain, this view was radical in the 18th century since the dominant way of encouraging scientific discovery was by awarding prizes. However, by providing a property right in exchange for the disclosure of a novel and useful invention, patent law supplied an incentive to perform risky and expensive scientific research. By embedding a property right in a patent, the market, not a biased government, could pick winners and determine value. A patent embeds a micro-economic property right in an invention from which market-based incentives are derived. From the property right, market competition is developed as multiple competing parties enjoy similar benefits of owning the fruits of discoveries in which they have vested financial interests. The patent system thus levels the playing field for different competitors as it encourages investment in scientific research. From the fair competition that arises in the system of patent rights that protects investment evolves economic and technological progress.

Without a limited exclusive right in a patent, there is simply no incentive to perform risky and expensive research because anyone can steal the invention with impunity. When the patent system is corrupted, anyone can infringe an invention and become a free rider. If the patent system does not protect the investment in research with a strong property right, there is not an opportunity to obtain a return on investment and thus the incentives to invent are absent. The ability to enforce patents with strong property rights is thus critical to a healthy patent system.

The U.S. patent system was, nevertheless, distinguished from European patent systems. In Europe, the costs of patenting on invention were extremely high, thereby limiting technological development only to the rich. By way of contrast, the U.S. patent laws allowed anyone to invent by reducing the cost of a patent examination and offering reasonable access to courts for enforcement. This democratization of invention enabled the worker on the shop floor to identify improvements in technologies that expanded technological progress.[3] Similarly, while large corporations rely on market power and brand awareness as competitive advantages, small companies require strong patents in order to compete against incumbents with high entry barriers.

Patent law represents a delicate balance. A patent is a disclosure of a useful discovery. Patents are required to be novel, non-obvious, useful and well described. In addition, there is a limited period of exclusive right of a patent, after which rights to the discovery flow to the public sphere and can be used by anyone. The disclosure of a novel scientific or technological discovery enables researchers to learn about a new innovation and to discover new ways to add to it. In this way, technology progresses and enriches the public in the long-run. In order to justify the investment and time costs of invention, a private property right is critical to enable a return on investment. No other system has reliably provided a justification to invest in solving complex problems.

In the 1960s and 1970s, U.S. patent law was split among the various regional U.S. Courts of Appeals. This period experienced a weak patent system with large corporations dominating market share; during this period entry barriers for small companies were very high because patent enforcement was uncertain. In 1982, the creation of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit with the Federal Courts Improvement Act consolidated patent appeals into a single unified court, which resulted in upholding strong patent rights until about 2000. It was during this period, from 1982 to 2000 that the venture capital industry evolved into a major economic force to create technology startups, including Apple, Microsoft, Google and Amazon, which are now the largest corporations by market capitalization in the world.

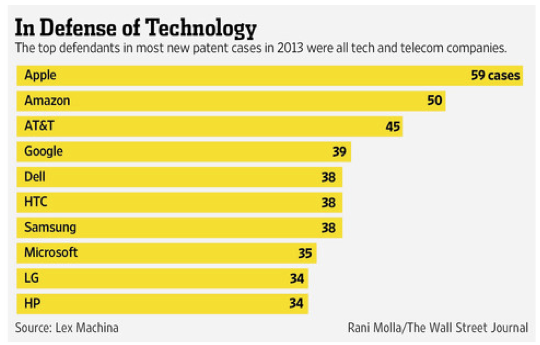

List of Top Patent Infringers, 2013

Whereas before 2000, the patent system was considered neutral, after 2000, the patent system was politicized with attacks from the far right and the far left. These critiques of the patent system led to a transformation that weakened patent rights and created uncertainty. A perverse and lasting consequence of these dramatic changes were increased examination and enforcement costs, which increased the costs and risks of investment.

After 2000, large technology corporations sought to make radical changes in patent law. In particular, since they were serial defendants in patent infringement suits, their main aim was to weaken the property right in a patent. The large technology corporations argued that patent holders were holding them up by excluding them from using small inventions in larger devices. This “hold up” by patent holders was enforced by injunctive relief barring further use as well as monetary damages. Consequently, the disintegration of patent law originated with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in eBay vs. MercExchange,[4] which invoked a high bar to justify an injunction.[5] Without an injunction, infringers could simply use a patented invention and, when caught, merely pay a fee for its use.[6] Numerous additional judicial opinions and the America Invents Act of 2011 further limited patent rights for patent holders, thereby undermining the incentive to invest in technology research. The fundamental property right in a patent was reduced to set of liability rules.[7] These dramatic changes enabled the “efficient infringement” model employed by large corporations that allow companies to get a free ride on others’ research investments. It is precisely these changes to patent law that are the source of the productivity growth declines we witnessed not only in the years since the recession, but in the years before the recession as well.

Ideological Critiques of U.S. Patent System and Recent Disruptive Policy Changes

Recent radical changes in patent law represent a detour from over two hundred years of consistent policy. The U.S. patent system is now unrecognizable from even fifteen years ago. What forces brought about these dramatic changes? I suggest that there was cooperation among radical ideologues on both the far left and the far right[8] that persuaded Congress and the courts to make unprecedented changes to patent law. For many decades, these groups were considered peripheral, but in a perfect storm they consolidated forces to make changes to the fundamental engine of technological change, with profoundly adverse consequences for economic development.

Traditionally, conservatives supported strong property rights in a patent and a strong patent system in order to supply an even playing field to all competitors. In recent years, however, large technology incumbents – charged with serial infringement – have gone off the reservation to relentlessly attack the patent system.

The primary impetus for attacking patents from the viewpoint of technology incumbents is to preserve monopoly profits and to attack competitors. By killing the baby in the cradle, incumbents get a free ride to use others’ technologies. This self-interest drives the narrative that patents are bad, weak, cover unpatentable matter, should have diminished valuation and that patent holders should be judged on whether they manufacture products covering the patents.[9]

The big technology cartel consists of about a dozen corporations that cooperate on the issue of attacking the patent system. These companies include several of the highest capitalized companies in the world.[10] Not coincidentally, the big tech cartel includes companies frequently sued for patent infringement. Note Chart XII illustrates suits initiated only in 2013. This chart provides clear evidence of “efficient infringement” by large technology companies.

The oligopoly of large technology companies operate in industry segments with relatively limited competition from entrants as a consequence of attacks on the patent system. With limited patent rights, it is difficult for start-ups to raise capital, which further benefits incumbents. Consequently, the attack on the patent system by incumbents is win-win for them since they preserve their monopoly profits while also constraining competition.

Furthermore, in a weak patent enforcement regime, high transaction costs provide a high barrier to enforce patents while large corporations get a free ride to use competitors’ technologies. As a key motive for raising transaction costs, the high bar for enforcement diminishes the incumbent costs of IP by devaluing patented inventions. However, since they can use others’ technologies with impunity, there is also a disincentive to invest in their own research programs.[11]

While the one-dimensional “patent troll” narrative is persuasive to policy makers, it does not justify the wholesale transformation of patent rights. The “patent troll” myth[12] is actually a straw man offered to preserve incumbents’ monopolies and monopoly profits. Nevertheless, invoking the “patent troll” myth has enabled large technology companies to engineer a transformation of the U.S. patent system to provide them with competitive advantages.[13]

One irony of the large technology incumbent attacks on the patent system is that they actually need strong patents to preserve their own investments in research. Their position is therefore the epitome of hypocrisy since their main objective is to increase costs for patent examination and patent enforcement so dramatically as to supply substantially high barriers to entry for all but the best funded competitors. In essence, then, the patent critics from the right are motivated by pure greed and a clear anti-competitive position.

The positions of anti-patent critics on the political left, on the other hand, have two main motivations. First, the socialist faction prefers “openness” as a justification to contravene private property rights, which reflects a naïve view of business operation. Second, one faction of the left prefers low drug prices and specifically attacks the pharmaceutical industry, largely ignoring the ex-ante costs of research and production.[14] Both positions were considered on the margins of debate until recent years.

In the case of the open society adherents, reflected in the open source movement, the left wishes to have free stuff: free software, images, video, audio, books and information. This ethos of openness seeks no barriers to the self-interest in using others’ property for personal use. The anti-patent progressives argue that it ought to be a public right to use others’ property. In the case of government funded research, they argue that they are entitled to use property from research that should be directed to the public interest.[15] Progressives seek consumer entitlements and freedom to operate. Quite simply, property rights embedded in intellectual property, designed to benefit the author or inventor of original works, interferes with their preference for open entitlement. Consequently, they seek a radical abandonment of the patent system. This naïve view, of course, ignores the source of extremely poor countries that simply lack an effective patent system that is required to preserve investment incentives.

In the case of the critics of patented drugs, there is a complete disregard for the extraordinarily high costs – typically over one billion dollars – on research of new drugs. Nevertheless, the left wants cheap drugs and are willing to compromise the entire patent system to seek their objectives.

The critique of the patent system from the far left begins at the top. President Barack Obama synthesizes the critiques of the patent system from the two leftist ideological factions. First, Obama openly attacked patent holders with rhetoric exactly tracking the big technology company lobbyist talking points.[16] In addition, in July, 2016, Obama published an article in JAMA discussing a presumed weakness in the Affordable Care Act, namely, the high cost of drugs. This attack on drug prices is a familiar critique, but Obama sees this critique on high drug prices as a justification for an attack on the entire U.S. patent system. It should be clear, then, that Obama’s radical ideological agenda is to undermine the patent system to seek his objective of obtaining cheaper drug prices. Since he blames high drug prices on the patent system, it is the patent system that is a target. This extreme position indicates the real motivation for attacking patents, not the “patent troll” narrative – a straw man – proposed by the big tech cartel.

There are a set of contradictions in the positions of the left regarding the patent system. First, it is sheer folly to believe that R&D can be performed for pure interest, say, by an academic with no profit motive. No profit-seeking business can operate without a functioning patent system to preserve a property right and enable a return on investment. Second, by ignoring ex ante costs, the left misses the fact that the public interest is harmed in the long-run since there is no incentive to perform risky research without preserving patent property rights. Third, by undermining patents, the left inadvertently helps market incumbents, which they despise. Fourth, the left inadvertently promotes inequality by harming the democratization of patents in so weakening patent rights that then require far greater capital. Fifth, by limiting patent rights to the middle class and poor in a weak patent system in which costs of entry are substantially increased, the left destroys middle class opportunities and institutionalizes poverty. The U.S. patent system for two hundred years provided anyone with an opportunity to supply their ingenuity and hard work to create something new, which was preserved by the patent property right for a limited time. The left would disregard these opportunities. Not only is the left naïve about the patent system, competition and economics, their ideology is inflexible. Most of the left’s arguments rest on ignorance, utopian myths or mistakes. For these reasons, their ideas have been marginalized until recent years during which many radical positions have been given a voice.

Interestingly, the radical left combined with tremendous big technology incumbent wealth and lobbying to generate a narrative that seemed persuasive about the need to attack the U.S. patent system. And so the patent system was dramatically modified and destabilized.

Legislating Away Patent Rights

The radical left and the tech incumbents combined to attack the patent system in different ways. First, the anti-patent advocates attacked patents in the courts. Starting with eBay in 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed dozens of patent cases, in almost all cases narrowing patent rights. The Court addressed issues involving standards for injunctions,[17] validity challenges,[18] patentability,[19] obviousness,[20] written description,[21] fee shifting[22] and willful infringement damages[23] over a ten year period. The big tech cartel complained about weak and improvidently granted patents, particularly involving software, for which the large technology companies were required to pay royalties. Consequently, the big tech cartel sought to reform the entire patent system through legislation.

Patent critics held the view that patents issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) were generally weak and that only a “golden patent” or gold-plated patent that endured a higher level of examination was valid.[24] Contrary to this view of the “golden patent,” the Court reviewed the issue of patent validity (35 U.S.C. § 282) in i4i vs. Microsoft[25]and upheld the two hundred year tradition of supporting a high bar to challenging patent validity. However, with very little substantive debate, and by relying on self-serving patent studies, the big-tech-cartel-authored America Invents Act, passed by Congress in 2011, enabled the PTO to establish after-grant patent reviews of previously issued patents. Though focused only on “novelty” and “obviousness,” the new after-grant patent review procedures dramatically altered the practice of patent law. The post-grant review (PGR), covered business method (CBM) and inter-partes review (IPR) mechanisms established a de facto two-tier examination system in the PTO, appealable only to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. While the pharmaceutical industry fought against the changes in “patent reform,” the big tech cartel was successful in instituting the new layer of examination procedures. The IPR process in particular effectively removed the majority of patent validity decisions from the judiciary back to the administrative agency that originally examined and issued the patents. Institution of the after-grant patent review system effectively did an end-run around the long-established traditions of establishing patent validity in the courts. Finally, in Cuozzo Speed Technologies v. Lee,[26] the Supreme Court affirmed the PTO’s IPR rulemaking authority.[27]

The net effect of the IPR procedures was to substantially raise the costs of patent enforcement by creating an expensive – typically at least several hundred thousand dollars – and time-consuming layer of reexamination in the PTO.[28] In most cases, the patents that are reviewed are ruled invalid because of discovery of additional prior art that is interpreted to challenge their novelty and non-obviousness. Nevertheless, if the big tech cartel complaints against “patent trolls” were the only concern, the after-grant patent review process would not be applied systematically to all patents. However, the application of after-grant patent reviews to almost all patents that are enforced in the courts suggests the ulterior motive of the patent critics to attack the patent system itself.[29]

In almost all cases, the after-grant patent review process was targeted against small entities and start-ups that sought to enforce their technologies against large tech incumbents. These start-ups need patent rights to compete against large incumbents. In about a decade, inventors went from being heroes of technology development to villains even as the U.S. economy shifted away from manufacturing in the 2000s and towards the innovation and licensing model. In an unprecedented move, the presumption of validity in a patent was shifted to a presumption of invalidity by the patent critic influence on Congress and the courts.

Nevertheless, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) established in the PTO to review granted patents is not without controversy. Under an aggressive PTO director with an anti-patent bias, the PTAB can be ordered to aggressively attack patent validity. For instance, the broadest reasonable interpretation (BRI) standard may be applied to patents rather than the narrower Phillips standard applied in the courts. Further, the statutory ability to amend claims has been systematically disallowed. These rules are asymmetric, benefitting the patent attacker and harming the patent holder. The combination of the PTAB rules tends to knock out a majority of issued patent claims, which delegitimizes the after-grant patent review process. In the very least, in order to maintain some legitimacy, the PTAB process of after-grant patent reviews must be neutral and fair, reflecting a need for courts to review these procedures or eliminate the process entirely and return patent validity decisions to the courts. Without neutrality, the anti-patent bias of the PTO can be seen as an abuse of discretion that tends to taint the PTO’s legitimacy. These anti-patent biases are also evident in the extremely low pass rates (e.g., under 10%) in some PTO art units. Congress did not intend to perpetuate an anti-patent bias of ideologues, empower ideological inflexibility or to enable a PTO power grab when it passed the AIA.[30]

From a periphery issue of “patent trolls” engaging in abusive and aggressive enforcement of occasional “bad” patents to the wholesale transformation of the patent system that raises transaction costs by twenty-fold to retest validity of previously examined and issued patents in a two-tier examination system, it should be clear that the anti-patent movement has succeeded in undermining the U.S. patent examination system. This fundamental transformation of the patent system to solve a minor “patent troll” problem is equivalent to burning down a house to stop a few termites. The cumulative effect of these dramatic changes in reexaminations is the disruption and destabilization of the patent system. Another effect is to shift power away from start-ups that need patents to promote competition and towards market incumbents that seek to protect their monopoly profits.

Yet, the attack of patents in the U.S. PTO is only one venue for criticism of the patent system. The patent critics also attack patent rights in the courts, limiting enforceability and damages as well.

The effect of the AIA’s systematic re-exam protocols and judicial changes in patent law were to effectively destroy the voluntary patent licensing model in the U.S. After all, without an injunction, with a high bar for enhanced damages and with a new mechanism for attacking granted patents in the PTO’s PTAB, why would anyone want to license new technology? This weakening of patent law enabled a new era of “efficient infringement” in which large technology incumbents and manufacturers ignore and simply infringe patents without concern for enforcement. If a patent holder could raise the capital resources to enforce the patent in court and could withstand an IPR, then the infringer could negotiate a license that they would initially have negotiated in a voluntary licensing regime. With the entry barriers for patent infringement enforcement at mid-seven and eight figures, the big tech cartel was immunized from the vast majority of patent infringement cases. However, small entities and market entrants were badly harmed by the new procedures. This suggests a fundamentally anti-competitive aspect of changes to the patent system.

Ironically, the primary motivation for initiating patent reform was absent since the main argument of the big tech cartel was that the exclusive property right in a patent supplied the patent holder with the opportunity to “hold up” the infringer by obtaining an injunction to force the infringer to stop using the patented invention. However, after eBay’s decision set a high bar for injunctions, this argument no longer applied to most cases. Rather, the big tech incumbents would refuse to deal with patent holders in a reverse hold up. The technology incumbents effectively transformed the U.S. patent system from one with strong rights to one with very weak rights that enabled the incumbents to refuse to deal with patent holders and to effectively ignore patents and voluntary patent licensing.

The combination of these patent law changes dramatically increased patent enforcement costs, particularly for small start-ups that require patent rights to compete with larger rivals. In fact, the new rules actually encouraged larger rivals to steal patented technology since there was no effective enforcement mechanism in most cases.

It should, then, be no surprise that the patent system was weakened in the period after 2000. The effects of these dramatic changes to patent law have been witnessed in the competitive configuration of technology rivalry, in the productivity growth decline trend and in the weak economic development data of recent years.

CLICK HERE to CONTINUE READING:In the next installment in this series Solomon will argue that the consistent pattern of investment declines are a key factor behind the productivity growth declines and the weak aggregate economic growth. He explains that technology transfers are actually blocked when a patent system is weak.

_____________________

[1] See List of Top Patent Infringers, 2013.

[2] See Solomon, N., “Adverse Effects of Moving from Property Rules to Liability Rules in Intellectual Property,” 2010.

[3] See Khan, B., The Democratization of Invention, 2005.

[4] eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006).

[5] The imposition of a high bar to obtain an injunction for patent infringement has several adverse consequences. First, without an injunction to protect a property right, liability rules are applied to infringement remedies, reducing patent infringement to a matter of assessing monetary damages. Second, with no injunction eligibility, anyone can use the patented property. In effect, this lack of an injunction brought an era of compulsory licensing. The patent holder can no longer control use of his property and, in particular, the exclusive use of patents is corrupted without protection of property rights via injunctive relief. Third, without an injunction, there is little incentive for companies to license technology, enabling “efficient infringement.” See Solomon, “Analysis of the “Four-Factor Test,” in Patent Cases Post-eBay,” 2010 and Diessel, B., “Trolling for Trolls: The Pitfalls of the Emerging Market Competition Requirement for Permanent Injunctions in Patent Cases Post-eBay,” 2007.

[6] The absence of an injunction enables a compulsory license.

[7] See Solomon, N., “Adverse Effects,” op. cit.

[8] See Atkinson, R., “Why Life-Sciences Innovation is Politically ‘Purple’ – and How Partisans Get It Wrong,” 2016. See also Solomon, N., “Three Dogmas of Intellectual Property Jurisprudence,” 2010.

[9] The “patent troll” narrative was originally developed by Intel Corporation to defend against companies seeking to license technology. The “patent troll” myth is targeted to companies that do not manufacture goods, but rather license technology to incumbents. The manufacturing nexus thus becomes a central part of the patent debates. It is particularly interesting that from 2001 to 2016, American manufacturing has dramatically declined. As Americans’ desire increases for inexpensive goods, American companies offshore their manufacturing to East Asian, particularly Chinese, companies. The U.S. manufacturing sector represents about 10% of the economy, with half of this from five companies (Ford, GM, Intel, Caterpillar and Boeing). The utopian dream that the U.S. is a manufacturing country is simply false. Rather, U.S. competitive advantage lies in innovation. By partnering with (i.e., licensing technology to) manufacturing companies in Asia, American innovators are part of an integrated global economy.

Nevertheless, the “patent troll” debate relies on the assumption that the U.S. manufactures goods. It is ironic, then, that the degradation of the licensing model in the patent debate benefits Asian manufacturers and harms American innovators. One can argue that the dominant business model going forward is the invent-and-license business model, not a manufacturing or vertically integrated business model, which requires intensive capital resources and limited profits. From Lincoln to Edison and from universities to Alphabet’s self-driving car technology, the non-practicing entity (NPE) invent-and-license business model is more efficient than the manufacturing model. Interestingly, the differentiating feature of eligibility for an injunction in patent infringement cases is the manufacturing nexus. In instituting the “patent troll” narrative, policy makers ignore the importance of patents to market entrants.

The “patent troll” arguments are primarily directed at companies that perform research, do not manufacture products and use business models that license technologies in a fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) way. IBM and Qualcomm, for example, are leaders of the invent-and-license business model. Therefore, the attack on the patent system that results from a narrow “patent troll” argument seems self-serving at best and self-destructive at worst. Attacking the licensing model in an era of decline of manufacturing is disingenuous.

Nevertheless, entities that acquire patents and abuse the judicial system present problems for which the courts are well suited to resolve.

Unfortunately, the popular revolt against patents stimulated by the “patent troll” narrative is largely without foundation since advocates only supply anecdotal evidence of a problem. Unlike incumbents, the CBO, ITC and CAFC do not see these issues as problems. See Khan, B., “Trolls and Other Patent Inventions,” 2013.

[10] Apple ($597B), Alphabet ($515B), Microsoft ($434B) and Amazon ($356B) are the four highest capitalized public companies in the world at the end of Q2, 2016.

[11] See discussion below on diminished investments by big tech companies despite record amounts of cash on hand.

[12] Some “patent trolls” or patent assertion entities (PAEs) aggressively exploit high litigation transaction costs to obtain settlements from alleged infringers. However, these market participants are in the minority. The majority of universities and small business entities that perform research in-house do not apply aggressive tactics to achieve unethical results. To attack the entire patent system for the problems of a few players is inefficient, with adverse consequences for incentives to invest in technology R&D.

[13] See Solomon, N., “The Problem of Oligopsonistic Collusion in a Weak Patent Regime,” 2010.

[14] Some progressives intend to narrow patent rights further by demanding march-in rights to NIH funded university biological invention. This extreme approach seeks to undo the benefits of Bayh-Dole’s commercialization success by requiring open licenses, the effect of which is to sabotage investment in innovation. Fortunately, the NIH itself is resisting this approach to removing exclusivity in university technology transfer.

[15] The argument that government funded research should yield technology that is freely open to the public has been tested in the past. However, before 1980, investors refused to commercialize government-funded university research. The Bayh-Dole Act provided universities with patent rights to government funded research. From this inspiration of embedding patent rights into government-funded research, the commercialization of inventions multiplied many times and stimulated an entire generation of technology transfer that partnered venture capital funded start-ups with university research. While the general research itself may have been publicly provided, the private rights in patents incentivize business commercialization of technology. Thus, there are ex ante incentives in patent rights as well as ex post incentives. The evidence therefore shows that the revolution in biotechnology was enabled by the provision of strong patent rights to government funded research.

[16] As Stoll, T., “Intellectual Property Laws,” 2016, states on p. 3, “In 2013, the President’s Council of Economic Advisers, the National Economic Council, and the Office of Science & Technology Policy drafted a report detailing five executive actions and seven legislative recommendations to fight patent trolls. The next year, during a town hall in Los Angeles, President Obama stated: ‘One of the biggest problems that we’ve been working on is how do we deal with these folks who basically are filing phony patents and are costing some of our best innovators tons of money in court.’ That’s right, the president of the United States said he thinks that patents are causing one of the biggest problems his administration is facing. He even mentioned patent reform in his 2014 State of the Union Address.”

[17] See eBay, op cit.

[18] MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U.S. 118 (2007).

[19] Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593 (2010); Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, 132 S. Ct. 1289 (2013) and; Alice Corporation v. CLS Bank, 134 S. Ct. 2347 (2014).

[20] KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007).

[21] Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 572 U.S. ___ (2014).

[22] Octane Fitness LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 1749 (2014) and Highmark Inc. v. Allcare Health Management Systems, Inc., 487 U.S. 552 (2014).

[23] Halo Electronics, Inc. v. Pulse Electronics, Inc., 579 U.S. ___ (2016).

[24] See Lemley, M., “What to do About Bad Patents,” 2005.

[25] i4i Limited Partnership v. Microsoft Corporation, 564 U.S. ___ (2011).

[26] Cuozzo Speed Technologies, LLC v. Lee, 579 U.S. ___ (2016).

[27] See Lee, P., “The Supreme Assimilation of Patent Law,” 2016, in which he argues that the Supreme Court’s attempts to equalize patent law with general legal principles may be misguided because of specialized features unique to patent law.

[28] IPRs are well-known as a harassment of patent holders. This is particularly the case when a third-party attacks a patent in an IPR. Also, when multiple infringers collaborate to bring serial IPRs, the system’s bias and illegitimacy is clearly illustrated. The European Patent Office eliminated similar trials of patent validity as a consequence of these harassing behaviors.

[29] Not surprisingly, the tech cartel seeks further patent reform. They have lobbied Congress to pass the Innovation Act, HR 9 and S 1137, which mandates one-way fee shifting if a patent holder loses in court, thereby forcing the patent holder to pay the infringer’s legal fees. The lobbyists push for this statute even after the Supreme Court reviewed two-way fee shifting (35 U.S.C. § 285) in Octane Fitness and Highmark. If enacted, this statute would further stymie legitimate patent enforcement.

[30] The ideological bias of the administration is contrasted with the neutrality of Art. III federal courts. Patent holders need a fair and neutral forum for adjudication of patent rights, not ideological bias and inflexibility.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

13 comments so far.

Chris Gallagher

October 3, 2016 09:52 amChris Gallagher

Eric Berend’s advice is sound. Send this Solomon post to inventors, candidates and anyone else you think might read it. “Efficient infringement” backed by AIA’s IPR is chilling investment in early stage innovation, clogging the wellsprings of our economy.

Eric Berend

October 2, 2016 12:35 pmThank you very much, Mr. Solomon. This is a complete statement encompassing nearly all of the vital details of this giant racket perpetrated upon the economic welfare of the United State of America, its putative Constitutional public interest, and the property rights of its inventors.

As an individual inventor, it is difficult to get people to listen long enough to reach even some of these details, in any discussion. Having a coherent narrative to point to, is very important. In my opinion, this needs to be disseminated widely, in some of the same fora in which the absurd – and phony – so-called “patent troll” canard was legitimized.

Edward Heller

September 30, 2016 01:11 pmFurthermore, Paul, it cannot be gainsaid that the opponents of harmonization also diverted substantial attention away from the larger threat.

Edward Heller

September 30, 2016 01:04 pmPaul, I do not doubt that the otherwise legitimate effort to harmonize was used as a Trojan horse.

Paul Morinville

September 30, 2016 11:36 amEdward Heller @ 7. “The AIA itself was primarily an effort to move the United States patent system to first to file.”

That’s not true. First to file was a false flag that the infringer lobby drove to the front of the debate. PTAB procedures were the real underlying driver for passage of the AIA. First to file would have only a marginal effect on large tech companies on its own – certainly not enough difference to pump hundreds of millions into congress to buy the legislation. Had PTAB’s not been part of the AIA, there would have been very little lobbying money spent to buy congress. It is obvious from the results that first to file was nothing and PTABs were everything.

For this reason, the infringer lobby, led by Google, repeatedly pushed first to file to the forefront of the debate using their massive public relations campaign in a direct effort to steer debate away from the extraordinary damage that PTAB’s cause to small startups and inventors.

Lawrence Glaser

September 30, 2016 10:53 amBy this logic Chinese companies should buy absolutely nothing. Just observe and read all the various inventions and use them. Why not? We are THAT STUPID. Now, roll the film forward by 10 years, 20 years, 30 years. US 60 TRILLION IN DEBT, 1 new job opens up for a tech position paying well. They cannot fill it, however, due to riots and looting.

China? Doing just fine, thank you USA.

Edward Heller

September 30, 2016 10:39 amI do not think this is entirely accurate.

The AIA itself was primarily an effort to move the United States patent system to first to file. That movement originated long ago in the negotiations regarding GATT-TRIPS, and is better known as harmonization whereby United States seeks to harmonize its patent laws with those of Europe and the rest of the world.

There is a legitimate debate as to whether a first to file system is a better system or not. Its main objective is to both eliminate secret prior art, and the ability of inventors to use their dates of invention to avoid prior. Both make patent rights uncertain and nontransparent even after examination.

This effort to move the United States to a first to file system culminated in a legislative aide effort that began in the early 2000’s and ended in the AIA of 2011.

IPRs are one more flavor of postgrant reexaminations that have been with us since the early 80s. Reexaminations were argued to Congress as necessary for patent owners to strengthen patents for litigation purposes. But they were not limited to re-examinations requested by patent owners. As result, accused infringers easily forced the patent owner back into the patent office where, for years and at great expense, the patent owner again had to prove patentability of his claims to an examiner. Any amendment to the claims could result in intervening rights and loss of past damages. Thus the goal of any litigation was to get the patent into reexamination (where there was no presumption of validity) for the purpose of forcing amendments to excuse past damages, and to increase litigation expense to the patent owner.

An inter partes re-examination system was added in 1999. But that did not prove popular. The reason that they did not prove popular was the continued presence of an examiner who took so long that the litigation could be over before the re-examination was complete thus frustrating the primary objective of forcing amendments and intervening rights. The goal of the “infringer bar” in the AIA was to eliminate the examiner in an inter partes re-examination. Thus we got IPRs.

Thus we see here two different efforts that extended over many years, going back to the early 80s, one regarding a reexamination system which was intended to weaken patent rights by essentially removing the presumption of validity and by forcing amendments that would cause intervening rights. The second effort was to move to a first to file in order to harmonize United States patent laws with those of Europe. Those two efforts culminated in the AIA 2011. But they were really independent and distinct efforts, one not clearly anti-patent, but the other overwhelmingly anti-patent.

Chris gallagher

September 30, 2016 10:25 amChris Gallagher ;

The IPWatchdog emergence of Neal Solomon has helped raise “patent reform’s” policy analysis to the careful scrutiny it deserves but rarely receives because of its complexity. With thoroughness, but not one wasted word Neal painstakingly untangles the economic, political and legal threads woven by the anti-patent left and profit-hungry right into a magician’s cape to make patent property seem to disappear. But as he shows, their magic is not mere “slight of hand”. Rather he reveals the grim reality of the efficient infringement they hide behind the curtain and why it is eroding our nation’s productivity.

EG

September 30, 2016 09:05 amHey Neal,

One last comment: I only wish Congress, as well as Our Judicial Mount Olympus would read this article, instead of accepting all the anti-patent rhetoric spewed by the media, as well as by unsubstantiated statements presented in amicus briefs as fact when they’re not.

EG

September 30, 2016 07:22 amHey Neal,

A great follow up to your first article. Many thanks for “setting the record straight” on why strong patent rights are important to innovation and productivity.

Anon

September 29, 2016 05:51 pmI chuckle and fully credit Mr. Solomon for writing such an exquisite article

(chuckling that this mirrors many of my longstanding views, and could almost pass for my own writing – Mr. Solomon though put this together nicely).

Night Writer

September 29, 2016 02:59 pmOne thing you might want to include in these articles is how integrated patents are to most big tech companies. Most big tech companies have in-house attorneys and the engineers work hard to come up with work that is worth a patent.

Reality.

step back

September 29, 2016 02:32 pmExcellent article.

Thank you.

(Too many naive people believe that invention, innovation, progress and improved life style are inevitable consequences of an unregulated market place; that inventors are commodity items. If a first one doesn’t come up with the next great thing then the guy or gal right behind will inevitably do so anyway. Even without patent protection. So why pay for something you will inevitably get for free? That is why they don’t protect inventors anymore. That is why this country is spiraling down that hubris tube that has swallowed up many other empires before, down into the dust bins of history. We are not exceptional. Just more of the same. Proud, arrogant, ignorant.)