Are you looking for a financial model to explain your patent develop and acquisition programs? Can you answer your CEO’s, or GC’s, question about how much to spend on patents? We present a method to tie your strategy to a firm business plan and calculate a return on your patent investment.

Are you looking for a financial model to explain your patent develop and acquisition programs? Can you answer your CEO’s, or GC’s, question about how much to spend on patents? We present a method to tie your strategy to a firm business plan and calculate a return on your patent investment.

A well-developed patent portfolio offers you the ability to defend your R&D investments against competitors, creates freedom to move into new markets, deters corporate asserters and can eliminate licensing fees. How do you produce such a portfolio? Start by identifying potential threats, then balancing reasonable patent portfolio investment with revenue retention, and finally calculating your risks.

This post presents an approach for modelling the value of a strategic patent portfolio for companies in the high-tech market (eg, cloud computing, semiconductors, mobile and networking). The biotech and chemical models are similar, but require modification for their specific patent risk challenges.

This post will cover a piece of a broader patent portfolio development process shown here:

At the beginning, identifying the group of companies holding patents you may need access to and who, in turn, may need access to your patents is the foundation of a patent assertion and counter-assertion strategy. If you sue me on patent A, I will sue you on patent X. But who comprises this group?

Identify neighboring and industry threats

In the early stages of a company’s life, it makes sense to develop a patent portfolio by filing patents that are focused on protecting the company’s R&D investment from competitors. These patents are directed at one’s own products, but often do little to address the broader set of potential patent risks.

Competitors are your most obvious potential asserters, but by no means the only ones you should take into consideration. A company’s patent threat pool extends well beyond its customers and competitors to include:

- Suppliers

- Partners

- Large, multibillion-dollar global corporations

- NPE’s (non-practicing entities)

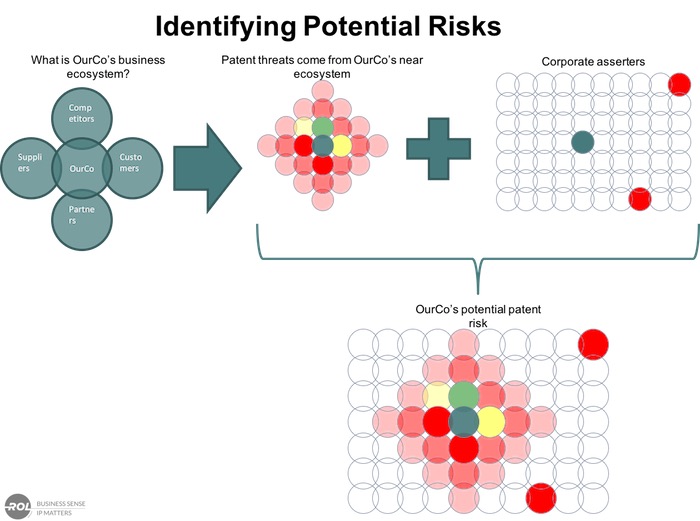

You can visualize these business relationships and patent threats by examining your ecosystem of business relationships and outlying threats. In the figure below, your company is the green dot in the middle. First look at your suppliers, competitors, partners and customers, then look to their suppliers, etc. Next add in known large corporate patent asserters. You quickly develop a list of potential patent threats.

Your patent portfolio can address the two primary sources of risk: your ecosystem and large corporate patent asserters. A well-developed patent portfolio reduces these threat sources significantly.

Calculate your risks

Next we need to understand your patent risk and its dollar value. This analysis calls for skills that, in addition to a traditional legal analysis, draw on market forecasting and prediction. It also requires comfort with handling unknown variables, approximations and estimates. Let’s define the elements of this analysis:

- An estimation of which companies are likely to assert their patents

- When that assertion might take place

- What the business cost might be

- A comparison of these estimations against your company’s existing and future patent portfolios

Keep in mind while performing this analysis that a “winning” patent strategy means something broader than courtroom victories and includes avoiding court altogether by deterring threats and substantially reducing payments to corporate patent asserters. A winning patent strategy has eliminate a threat before it appears or materially improve a license agreement.

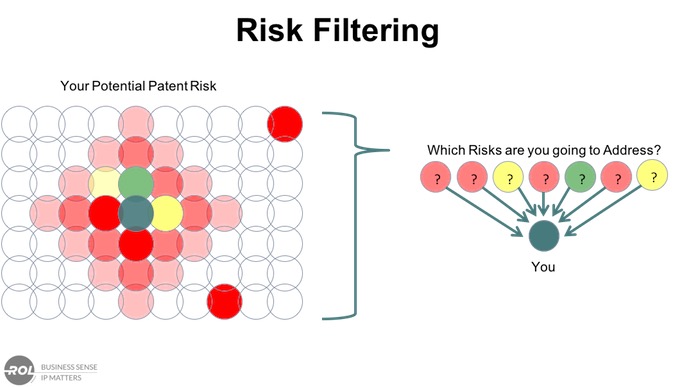

Your risk calculation should filter out less likely potential asserters to enable a focus on the highest threats. Each potential asserter poses a unique risk, has a unique value and should be considered individually in your overall strategy. Starting with your list of potential patent risks (companies that hold patents in your space or large corporate patent asserters), identify the risks that are the most concerning. You can use a few shortcuts:

- To whom are you most important?

- Which competitors are most threatened by your business?

- Which customers are paying you the most revenue?

- Which suppliers are trying to move upmarket or are the most crucial?

- Which companies in your list have demonstrated a willingness to promote, assert or litigate their patents?

- What strategies, other than patents can you use to reduce your risk?

Usually you know your biggest risks immediately, but it’s important to apply filters to your list of companies to decide which are most likely to assert. Remember, this list won’t remain static – it can and will evolve over time. You will need to revisit this process on a regular basis.

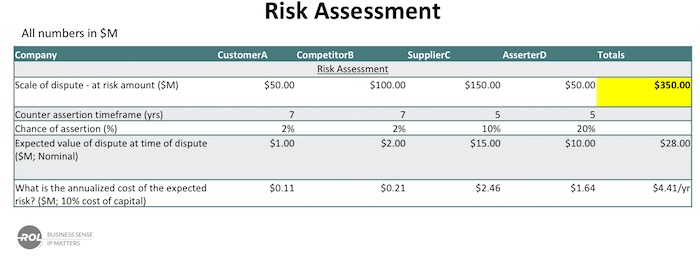

Now you are ready to use the risk of assertion to calculate the expected value at the time of the future dispute. As a reference point, it is useful to consider what it would cost your company to pay the asserter based on the expected value in equal payments – taking into account the cost of capital. Thus, the value of equal payments (as if the risk was a mortgage) can be computed to estimate the annual cost of the risk.

In accounting, the cost of capital is the minimum return that investors expect for providing capital to the company. Companies decide whether to invest in a project based on whether the costs of the project, adjusted for the cost of capital, will be less than or greater than the future expected value. Using the cost of capital ensures that the investment in risk mitigation represents a good return on investment. Ask your chief financial officer what cost of capital or internal rate of return they use in business models. While a new start-up may have a 33% cost of capital, most high-tech companies tend to set their cost of capital somewhere between 9% and 15%.

Find technology overlap

A winning counter-assertion portfolio has patents that act as credible threats to multiple potential asserters’ revenues. The development, or purchase, of these patents reduces the investment necessary for risk mitigation because such patents address multiple threats simultaneously. They reduce risk for multiple asserters, but they only have to be developed, or purchased, once. As a result, finding technology areas or market segments where multiple potential asserters derive revenue will allow any company to amplify the value of patent investment.

Identifying the right technology areas requires an analysis of each potential asserter’s key revenue sources. This analysis should include:

- Which products and technology areas are strong revenue sources

- The asserter’s growth (or negative growth) rates

- The geographic regions producing those revenues. Because patents are country specific, knowing in which country their critical technology has the largest presence

Remember many potential asserters are public companies and this information is regularly provided to their shareholders and the regulatory authorities. Additionally, market analyst reports and third-party product market analysis can be very helpful.

The key is to identify those strategic areas in an asserter’s business against which you’ll need to focus your patent counter-assertion efforts. Having a counter-assertion against a declining business may provide poor negotiating leverage. However, focusing on a strategic growth area for the company or technology in an area where an entire industry is expanding is likely to provide better negotiating leverage.

Is this sort of forecasting always accurate? Clearly not, but the important thing is that your predictions should be close enough to know whether patents in that area will remain important to your potential asserter. Once key market segments have been identified, consider areas of overlap across all your greatest threats.

This process is straightforward. You have previously identified technology areas where your customers, competitors, suppliers and other asserters do business, and know the revenues from each segment. The only missing piece is adding up their revenue to find the total potential impact of each technology area and the total exposed revenue for each potential asserter (if you had patents in that technology area, how much revenue might you be able to impact across multiple risks?).

Using this model, your company can prioritize your patent investment far more strategically. Those asserters deemed a low risk (either in terms of their technology areas and/or the lost cost of assertion) will define your lowest priority patent investments. Similarly, while your company may identify areas that seem to indicate high revenue exposure, it’s important to understand whether the market in those segments is growing or on the decline. In the latter case it’s wiser to reduce your patent portfolio investments in what could otherwise appear to be a valuable market area.

Of course in those areas where you find a combination of strong potential impact across multiple potential asserters and a growing market segment, the benefits of patent investment become obvious. It bears repeating that by our previous definition of “winning”, your company does not have to have counter-assertion assets against all of the revenue generated by all of the companies. You only need to have counter-assertion assets covering sufficient revenue in your potential asserters’ strategic market segments to present a credible counter-threat.

Risk mitigation – identify and fill portfolio gaps

Your ultimate goal is to mitigate risk at the lowest possible cost to your company. Consider some of the factors for your counter-assertion strategy:

- The strength of your current patent portfolio

- The company’s overall financial health

- Whether or not your company is involved in litigation that could affect your asserters

- General trends in the industry and patent landscape

If you’ve calculated the basic total annual risk using our methodology, how can you decrease your estimated spend while still providing adequate patent protection? A great place to begin is by setting a break-even point (mitigating some of the risk through patent litigation defense, inter partes reviews, oppositions, and other non-patent related business leverage). In other words, you won’t eliminate your entire patent risk through your patent portfolio, rather scale your potential annual spend down by the amount of coverage you want.

In the example below, the annualized cost of all the risk is about $4.4M. The company has decided to use their patent portfolio to reduce this risk by 66%; they have decided that ? of their risk will be alleviated by their patent portfolio and ? through business relationships, defensive litigation, and other strategies. By taking care to look at overlaps, the annual cost of the program is $1.6M/year. Now, you can say to your executive team that we face an estimated $350M in patent risk, with an expected value of $28M. Through our overall patent strategy, we believe we can mitigate this risk for an investment of $1.6M/year.

Let us now look at whether patent purchases or internal patent development would be the wiser course. Assume for this example, that your company has no patents identified to help with your counter-assertion strategy (this actually occurs in high-tech). In today’s market, a typical patent purchase of between three and eight assets including one charted patent family costs between $500K-$1M. Ten such packages with ten charted patents would potentially deliver between thirty and eighty assets–reasonably mitigating patent risk well within your company’s budget of 1.6M/year. Our post “10 Best Practices in Corporate Patent Buying” has more information on establishing a corporate patent buying program. Our 2015 patent market survey (“2015 Patent Market – a Good Year to be a Buyer”) has data on current prices for patent packages.

Could you also develop patents to fill these holes? It’s possible, however those developed patents will have later priority dates and only about 3 to 5% of internally developed patents will have strong enough evidence of use cases (EOUs) to stand up in a counter-assertion position. A combination of purchased and developed patents is likely the best choice for many companies. For companies with larger current portfolios or a longer history of patent filings, the answer is likely different.

Analyzing your counter-assertion potential

To understand your counter-assertion potential, it helps to create a playbook for each potential asserter. In this example, YouCo would have playbooks for Customer A, Competitor B, Supplier C and Asserter D. These playbooks contain the analysis of each asserter’s business interests and revenues (shown above), and the specific patents inside YouCo’s patent portfolio which could be used for counter-assertion. The qualification process is described in more detail in our article in IAM Issue #72 “The Strategic Counter-Assertion Model for Patent Portfolio ROI” by Kent Richardson and Erik Oliver.

Creating playbooks offers companies a method for knowing when there are enough patents in a portfolio to mitigate the risks they have identified and where to strengthen coverage. We find that a typical well-tested playbook for a potential asserter will have between three and 10 patents (and the corresponding family members) affecting a comparable amount of revenue to your own company’s revenues. Overall portfolio size still comes into play, but the value drivers for the negotiation are primarily in the playbook. For simplicity, we did not model how long a patent will stay in the playbook in this example, but models should take this into account.

You can calculate the rate of return using the following logic:

- Expected value of the risk: $28M

- Amount of value mitigated from patent development and buying: 66%*28M = 18.4M

- Average number of years of risk: 6 years

- Annual investment: $1.6M

- Rate of Return: 25%

So in answer to the three questions originally posed by your CEO:

- We should invest $1.62 million in patents for counter-assertion this year.

- We should get patents in cloud infrastructure and database software.

- The patent development programme will address 66% of an expected value of a $28 million patent risk.

- The rate of return over six years is 25% per year.

There are some important thoughts about presenting models like this. Most importantly, the model attempts to select the most important, but not all, business factors for the particular patent strategy. Some models will be more complex; others can be simpler. Second, the model provides a framework for discussion about the patent strategy. Without the model, discussions can careen all over the landscape without anchoring on the most important elements of your patent strategy. Third, the model allows you to adjust your strategy over time, but still keep a basic framework for future years. Finally, models such as this are commonly used to determine whether a particular project or business strategy should be pursued; by using this model, you are adopting the same business language that other businesses in your company use.

Conclusion

The model mitigates patent risks, provides a financial foundation for your patent investments and gives you a testable patent strategy. This model provides a framework for discussion with other members of the corporate team and for developing your company’s patent portfolio. It explains not only why you get patents, but which patents are more likely to be valuable, which companies pose the greatest risks and ultimately how much risk you are willing to mitigate. The model is not perfect, but it allows you to structure conversations with executives, legal, finance, engineering – each group having different interests, but each interest captured in the model.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.