Globally there are approximately 7,000 medicines in development to treat and cure a wide variety of diseases. Of these, more than 5,000 are in development in the United States. [1] The numbers are revealing, if not shocking. This work is done in the U.S. because it is incentivized and encouraged through a robust intellectual property rights protection environment. The United States undeniably provides the most comprehensive intellectual property rights for biopharmaceuticals and the industry thrives here as a result. It’s difficult to argue that the strength and success of the U.S. biopharmaceutical industry is uncorrelated with the IP protection available here.

Globally there are approximately 7,000 medicines in development to treat and cure a wide variety of diseases. Of these, more than 5,000 are in development in the United States. [1] The numbers are revealing, if not shocking. This work is done in the U.S. because it is incentivized and encouraged through a robust intellectual property rights protection environment. The United States undeniably provides the most comprehensive intellectual property rights for biopharmaceuticals and the industry thrives here as a result. It’s difficult to argue that the strength and success of the U.S. biopharmaceutical industry is uncorrelated with the IP protection available here.

Given this and the wider benefits of biopharmaceutical research and development, it’s tremendously disappointing that the recently negotiated Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Trade Agreement fails to deliver sufficient IP protection for biologics. Much of the continuing controversy plaguing the TPP Agreement surrounds data exclusivity protection for biologic medicines and the future of the agreement may hinge on precisely this issue.

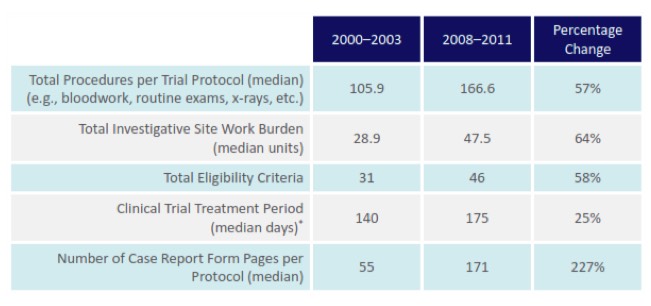

First, it is worth exploring why this is an issue and what the debate revolves around. Due to the great expense of bringing a new medicine to market, the intellectual property rights protection granted to innovators is disproportionally important for the biopharmaceutical industry. Current estimates place the preapproval cost of developing a biologic at close to $1.2 billion and the time needed to recover these costs is between 12.9 and 16.2 years.[2], [3] Granting these numbers are highly controversial, drug development is undeniably costly and the process requires a significant investment of both time and money. Of great importance to the current TPP debate is the fact that the complexity of clinical trials and the approval process has increased considerably, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Trends in Clinical Trial Protocol Complexity[4]

(PhRMA, 2013)

As increasingly lengthy clinical trials are required for FDA approval, the medicine’s effective patent life is reduced. Biopharmaceutical firms seeking approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will have considered 5,000 to 10,000 experimental compounds over a period of ten to fifteen years, and typically only one will gain approval. Moreover, a mere three out of every ten pharmaceuticals developed will recover the financing required for their development, leaving those few blockbuster products to cover the expenses of numerous failures. All the while, the uniqueness of the innovation is threatened by the ease of their replication. Innovative biologic firms are significantly disadvantaged if biosimilar firms do not have to bear the research and development costs and are still able to bring a generic version (biosimilar) to market, compete and sell the drugs. Hence, the critical importance of data exclusivity protection.

In earlier IPWatchDog posts (here, here, here), I have described the importance of data exclusivity and its role in incentivizing biopharmaceutical research and development.

Data exclusivity protection allows for a period of time following marketing approval during which competing firms may not use the innovative firm’s safety and efficacy data, from proprietary preclinical and clinical trial results, to obtain marketing authorization for a generic version of the drug. From the moment when the compound first shows medicinal promise, data is generated and compiled, a process that is both expensive and time consuming. Data exclusivity provides the innovative firm with a period of protection for their investment in clinical trials and data collection, regardless of the length of time required to bring the drug to market.

In contrast, data exclusivity protects the tremendous investments of time, talent, and financial resources required to establish a new therapy as safe and effective. This is accomplished by requiring competing firms seeking regulatory approval of the same or a similar product to independently generate the comprehensive preclinical and clinical trial data rather than rely on or use the innovator’s data to establish safety and efficacy of their competing product. Alternatively, the competing firm may wait a set period of time after which they are able to utilize the innovator’s prior approval in an abbreviated regulatory approval, eliminating the need for independently generated data. Data exclusivity is not an extension of patent rights, and it does not preclude a third party from introducing a generic version of the innovator’s therapy during the data exclusivity period, provided that the innovator’s data is not used to secure marketing approval.

The distinction between patent rights and data protection is an important one, and apparently not completely understood – even by those who purport to have the authority to write about such stuff. A recent article in the Washington Post states “The ‘data exclusivity’ granted by the deal means that competing companies making biosimilar drugs cannot bring their products to market, which could bring down prices.” This is blatantly untrue. The data exclusivity protection provided in the TPP agreement does not prevent biosimilar firms from bringing their products to market. Rather, it prevents them from relying on the innovator’s data to secure regulatory approval. The biosimilar firm is still able to bring their product to market, providing they generate their own data establishing the product’s safety and efficacy.

The crux of the issue is how long biosimilar firms are required to wait before they are allowed to take the regulatory shortcut and use the innovator’s data to secure regulatory approval. Under U.S. law, the innovator’s data is granted 12 years of exclusivity. This period was vigorously debated and analyzed before being established. And yet, even this timeframe fails to provide the minimum (12.9 years) number of years needed to recover the development costs. Under the proposed TPP Agreement, innovators would only realize 5 years of protection. Critics claim that this is a victory for the pharmaceutical industry, noting that Peru, Vietnam, Malaysia and Mexico who currently provide no data exclusivity for biologic medicines, will have to wait at least five years before allowing biosimilars onto the market. Notably these are not innovator countries, yet they fully enjoy the benefits of costly pharmaceutical innovation. Removing the incentives to innovate cannot be considered a victory by any stretch of the imagination.

The benefits of costly pharmaceutical innovation should be available to all, but the innovator should be rewarded as well. Under the proposed TPP Agreement, biopharmaceutical innovators are stripped of their incentives to invest in the risky, expensive, time-consuming drug development process. If we believe that this will not impact the future of medical innovation, we are short-sighted and naïve. Five years of data exclusivity protection will save money for the non-innovating nations, but it may cost us all a future of breakthrough therapies and cures.

[Kristina]

________________

[1] PhRMA. 2015 Biopharmaceutical Research Profile

[2] DiMasi, Joseph A. and Henry G. Grabowski. The Costs of Biopharmaceutical R&D: Is Biotech Different? Managerial and Decision Economics, vol.28, 2007.

[3] Grabowski, Henry, Genia Long and Richard Mortimer, Data Exclusivity for Biologics, Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery, January 2011, vol.10, pp.15-25.

[4] The complexity of the clinical trials results from a variety of factors including a shift in focus from acute to chronic illness, collection of increasingly intricate data elements, closer attention to each element of trial design, and concern about potential requests from regulatory agencies (Getz, Campo and Kaitin, 2011).

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

5 comments so far.

Dianne Foster. ARNP

October 28, 2015 01:16 amHow much of original R and D is already subsidized by the public? Would you comment on the “evergreening” of older drugs in the TPP? We’re already seeing huge swings in price in very old drugs, even from one pharmacy to the next….

T2

October 27, 2015 02:08 pmAs drug prices across the board continue to rise, for both innovators and generics, the “12.9” yrs needed to recoup costs (which was already a qualified number) rapidly goes down. Appropriate data exclusively (as well as other forms of RA exclusivity, e.g., NCE, pediatric, etc) is critical, though would like to see an end of the high US drug prices subsidizing ROW.

Jamie

October 27, 2015 09:46 amThanks for the article. It occurred to me while reading it that another (sub-)point in favor of data exclusivity is that if incentives to innovate are reduced, of course innovation will be reduced, so it’s a good thing everybody is satisfied with the presently existing pharmaceuticals and treatments. Why do people seem to assume that pharmaceutical innovation will continue when it is no longer profitable, or when other investments of capital can provide a better return?

Gene Quinn

October 26, 2015 04:27 pmEdward-

Not to spoil Kristina’s next article, but she is already working on another article along the lines of your suggestion. I’ve seen a draft that is very close to completion. Looking forward to publishing it soon.

-Gene

Edward Heller

October 26, 2015 02:44 pmWhat we need is a bit of patent reform that provides a patent a term the longer of 20 years from filing or 17 years from the date of government licenses a covered product to be marketed. Then we can dispense entirely with data exclusivity concerns.