The brief history of graphics processing units, or GPUs, stems back to 1999 when Santa Clara, CA-based Nvidia Corporation (NASDAQ:NVDA) unveiled the first dedicated GPU unit for the personal computer platform. Other visual processors existed throughout the 1990s, but Nvidia’s product seems to be the first commercially successful stand-alone GPU. As computer graphics became more sophisticated by the end of the late 1990s it became necessary to move graphics processing functions like engine rendering and triangle setup or clipping to their own processing chips, enabling the main computer processing unit, or CPU, to focus resources on other operations. Nvidia’s GeForce 256 was released on August 31st, 1999, with a 256-bit graphics core, much greater than the 64-bit CPU that powered graphics and audio on the Nintendo 64, which was the leader in video gaming graphics processing at the time. The GeForce 256 also had a 128-bit memory interface and could render 15 million triangles per second and 480 million pixels per second. Never before had so much processing power been focused on computer graphics.

Through the 2000s, Nvidia and rival GPU maker ARM Holdings (NASDAQ:ARMH) ended up getting pushed out of certain sectors like mobile GPU, which largely became the domain of Apple Inc. (NASDAQ:AAPL) However, Nvidia and ARM have been able to stick around thanks to the console gaming industry. In terms of personal computers, Nvidia dominates with a market share of 76 percent as of the fourth quarter of 2015, leaving only 24 percent to ARM. In terms of gaming consoles, however, AMD is leading in the current generation as its accelerated processing unit (APU), which offers CPU and GPU functionality on a single chip, are utilized in both the Xbox One and the PlayStation 4. Overall, the market value for discrete GPU units has increased steadily from $3.3 billion in 2009 up to an expected $7.6 billion through 2015, according to a white paper released from market research firm Jon Peddie Research; compared to integrated GPU units, which don’t provide their own random access memory (RAM), discrete GPU units are capable of processing video games and other graphics-intensive applications which require high pixel power.

It doesn’t look like Nvidia is willing to let up on its lead in gaming GPUs to judge by a new chip recently unveiled by the company near the end of August. The Nvidia GeForce GTX 950 offers dual processing clusters running a total of six streaming multiprocessors. This GPU only offers a 128-bit memory bus, just half of the bit capacity of the company’s seminal 1999 GPU product, but the unit is capable of processing video gaming content with resolutions up to 1080p, which is the standard for many video games for current generation consoles like the Xbox One or the PlayStation 4.

Perhaps the most interesting characteristic of the GeForce GTX 950 is its low price. Nvidia has typically stayed out of the low end budget GPU processing units, content to leave that sector to both AMD and Intel Corporation (NASDAQ:INTC). However, the GeForce GTX 950 retails for $160, representing a serious foray into the low end GPU market which covers most units selling for under $200. It’s not optimal for video games which utilize 4K resolutions but models handling those resolution sizes can cost many hundreds of dollars per unit, made worse by the fact that 1080p is still the pixel resolution standard for video gaming so the extra firepower is largely unnecessary as of yet.

Of course, we’re not likely to see this Nvidia model popping up in the current day’s top selling consoles but increased competition in the budget gaming sector is interesting to note. For computer building hobbyists looking to create their own personal gaming computer, graphics and video processing cards are typically the most expensive component to provide for the machine. Providing a GPU that costs less than $200 gives gamers the capability to construct budget gaming PCs for $400 or less. That’s still higher than current retail prices for the $350 that the Xbox One and PS4 cost in some online stores but PC gaming offers some notable upsides, such as the ability to purchase entire catalogs of games through online digital gaming platforms like Steam at a fraction of the cost of a single console game when it’s newly released, which is typically about $60 per unit.

The video game industry is going through some interesting changes in recent months and we’ve been profiling some of this new movement in the sector here on IPWatchdog. In our coverage of this summer’s Electronic Entertainment Expo (E3), we noted how app-based gaming was becoming a much larger field within the video game industry and it’s expected to rake in $22 billion in revenue in a market that’s forecasted to total $111 billion by the end of this year according to technology research and advisory company Gartner Inc. (NYSE:IT)

Moore’s Law is also playing a pretty strong role in the budget PC gaming world. This May, we acknowledged the 50th anniversary of the publication of an article written by then-Fairchild Semiconductor R&D director Gordon E. Moore in the journal Electronics which espoused Moore’s idea that computer processing power would essentially double every two years. It’s a major reason why netbooks and many other computing devices of today cost a small percentage of what Macintosh computers sold for in the 1980s when adjusting for inflation, despite the fact that today’s computers are far superior to those older models in many ways. Now it’s not impossible to purchase the barebones processing equipment to a personal computer for about $50 USD, although that doesn’t include a display, controller or GPU that would be necessary for gaming.

It may interest our readers to know that Nvidia has recently been active in trying to license certain semiconductor technologies to third parties, such as its Kepler GPU architecture which the company first unveiled in 2012. According to online tech publication AnandTech, GPUs developed in the future by Nvidia will be available at time of tape-out, or right after the final phase of the design cycle, so that third parties can integrate those chips more quickly. There are those who have interpreted the company’s decision as proof of the difficulties Nvidia is having in breaking into growing markets despite its dominance in personal computer GPUs.

Licensing activities can have a pretty remarkable effect on specific tech sectors and we need only go back to the IBM/Apple clone wars of the 1980s and ‘90s for an example. Information technology developer IBM Corp. (NYSE:IBM) sued computer maker Eagle in the 1980s for infringement of IBM’s basic input-output software (BIOS) but largely allowed cloning of the personal computer that IBM had constructed largely from off-the-shelf parts available to anyone. By 1986, computer developer Compaq had constructed a truly compatible IBM-compatible clone and future generations of IBM compatibles performed and sold better than IBM’s product, keeping the IT giant out of a market that it helped to create. Apple shortly followed IBM into the personal computing market and maintained a closed system that required any clones to use read-only memory (ROM) from a donor Macintosh. Apple tried to build a low-end Mac clone market in the mid-1990s, licensing its tech to now-defunct vendors Power Computing and Radius. Unfortunately, those products hit the market in the same year that Microsoft Corporation (NASDAQ:MSFT) released Windows 95, its first operating system (OS) software with a graphical user interface that was commercially competitive with Apple’s Macintosh OS.

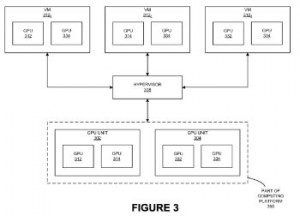

We’re always interested in getting a look at corporate research and development operations through the lens of a company’s IP portfolio and we thought we’d at least look at a pair of patents issued to Nvidia recently from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to get a sense of its latest innovations. The title of this patent might be a mouthful but gamers might be interested in the incredible  graphics processing power supported by the technology discussed within U.S. Patent No. 9098323, titled Simultaneous Utilization of a First Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) and a Second GPU of a Computing Platform Through a Virtual Machine (VM) in a Shared Mode and a Dedicated Mode Respectively. The method protected here involves executing a driver component on a computing platform’s hypervisor, providing support for hardware virtualization of a second GPU in the hypervisor, defining a data flow path between the VM and both GPUs and providing a capability to the VM for utilizing the first GPU in a shared mode with another VM while simultaneously dedicatedly utilizing the second GPU. This innovation overcomes problems with restricted scalability in VMs causing performance problems when additional graphics processing from a second GPU is required. Scaling computer resources up to accommodate multiple GPUs is also a focal point of U.S. Patent No. 9087161, entitled Asymmetrical Scaling Multiple GPU Graphics

graphics processing power supported by the technology discussed within U.S. Patent No. 9098323, titled Simultaneous Utilization of a First Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) and a Second GPU of a Computing Platform Through a Virtual Machine (VM) in a Shared Mode and a Dedicated Mode Respectively. The method protected here involves executing a driver component on a computing platform’s hypervisor, providing support for hardware virtualization of a second GPU in the hypervisor, defining a data flow path between the VM and both GPUs and providing a capability to the VM for utilizing the first GPU in a shared mode with another VM while simultaneously dedicatedly utilizing the second GPU. This innovation overcomes problems with restricted scalability in VMs causing performance problems when additional graphics processing from a second GPU is required. Scaling computer resources up to accommodate multiple GPUs is also a focal point of U.S. Patent No. 9087161, entitled Asymmetrical Scaling Multiple GPU Graphics  System for Implementing Cooperative Graphics Instruction Execution. It claims a multiple GPU graphics system with a plurality of GPUs, each having a plurality of graphics rendering pipelines, a serial bus connected coupled to at least one GPU enabling the GPU to communicate with the computing system, a GPU output multiplexer and a controller operating both the GPUs and the output multiplexer so that the GPUs cooperatively execute graphics instructions to provide an asymmetrically rendered graphic output. This innovation seeks to increase the bandwidth traveling between a GPU and the rest of a computer system to encourage upward scalability of the GPU platform when rendering three-dimensional graphics.

System for Implementing Cooperative Graphics Instruction Execution. It claims a multiple GPU graphics system with a plurality of GPUs, each having a plurality of graphics rendering pipelines, a serial bus connected coupled to at least one GPU enabling the GPU to communicate with the computing system, a GPU output multiplexer and a controller operating both the GPUs and the output multiplexer so that the GPUs cooperatively execute graphics instructions to provide an asymmetrically rendered graphic output. This innovation seeks to increase the bandwidth traveling between a GPU and the rest of a computer system to encourage upward scalability of the GPU platform when rendering three-dimensional graphics.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

No comments yet.