No one should have been surprised when The Washington Post ran Here’s why patents are innovation’s worst enemy by Vivek Wadhwa. It was only a matter of time before universities standing up to the patent reform behemoth drew retribution. Last year they were attacked as patent trolls. Now we hear that patents and licensing are irrelevant or even harmful to innovation. While the attack hits a larger target, a prime focus is discrediting university technology transfer before the patent reform debate kicks into high gear.

No one should have been surprised when The Washington Post ran Here’s why patents are innovation’s worst enemy by Vivek Wadhwa. It was only a matter of time before universities standing up to the patent reform behemoth drew retribution. Last year they were attacked as patent trolls. Now we hear that patents and licensing are irrelevant or even harmful to innovation. While the attack hits a larger target, a prime focus is discrediting university technology transfer before the patent reform debate kicks into high gear.

Fortunately, a new study showing that academic patent licensing contributed more than $1 trillion to the U.S. economy over eighteen years blows the stuffing right out of that straw man. We can only hope Congress gets the message before it turns the patent system into a weapon to squash inventors.

We could see the storm clouds gathering weeks ago when IP Watchdog flagged Robin Feldman and Mark Lemley’s study Does Patent Licensing Mean Innovation. Gene Quinn aptly titled his column Flawed survey erroneously concludes patent licensing does not contribute to innovation. Other IP Watchdog commentators did a masterful job exposing the shortfalls in Professors Feldman and Lemley’s work.

The Wadhwa article and the Feldman/Lemley study appear timed to influence the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate Small Business Committee which begin considering the pending patent reform bill this week. The argument that patents and licensing are impediments to innovation seems laughable but could mislead many as this message is constantly hyped by those skilled in working the media.

Fortunately, a new study sets the record straight. The evidence showing the substantial contribution academic-industry patent licensing makes to our economy should be carefully considered before legislators are stampeded into passing a bill that strangles this golden goose. The commercialization of university patents is one of the few parts of our economy that grows consistently through good times and bad.

[Joe-Allen]

Nevertheless, Mr. Wadhwa uses the Feldman/Lemley study to make a sweeping indictment of the U.S. patent system:

A new paper, Does Patent Licensing Mean Innovation, by Robin Feldman, of the University of California-Hastings Law School, and my colleague Mark Lemley, of Stanford Law School, dispels what doubt there may have been about the innovation value of patents. They analyzed the experience of real companies to see how often patent licenses actually spur innovation or technology transfer when patent holders assert their patents against companies. (emphasis added) They found that almost no new innovation resulted. When patents were licensed, regardless of whether they were licensed from companies, patent trolls, or universities, they were practically worthless in enabling innovation.

The study underscores the need to broaden the focus of patent-reform efforts.

Note the premise of the study highlighted above. Should we be surprised that companies who are notified that they may be infringing someone’s patent don’t view this experience positively? Should we expect patent owners sending such notifications against copiers to say that the prospect of a patent law suit unleashes their creative juices? But what if the study had surveyed those who formed their companies around patents or licenses? They seem the most likely to say that patenting and licensing increased innovation—but they weren’t even asked.

From this flimsy foundation Mr. Wadhwa boldly plunges ahead:

It isn’t just the NPEs that are a problem. The results were the same when the licensing requests or lawsuits came from product-producing companies and universities; patent licensing rarely led to new products or technology transfer. It was the same for computer and electronics companies as for life-science companies: the research shows that licensing in response to patent demands is not serving much of an innovation-promotion function at all, no matter what type of party initiates the licensing demand. It casts significant doubt on a common justification for a large slice of patent activity.

Even though the study did not examine the licensing that occurs when a company itself initiates the approach to a patent holder or the substantial cross-licensing activity taking place between competitors, the net effect is likely to be the same.

Patents simply have no role in the era of exponential technologies. We don’t need toll roads for innovation, we need faster highways.

Contrary to that claim, the just released white paper by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO) shows traffic on the patenting and licensing super highway is zipping along at an impressive pace. The title alone speaks volumes: Academic-Industry Patent Licensing Contributed up to $1.18 Trillion to U.S. Economy Since 1996. Here’s the summary of the findings:

A newly released study, commissioned by the Biotechnology Industry Organization (BIO), documents the significant impact academic technology transfer makes on the U.S. economy. The Economic Contribution of University/Nonprofit Inventions in the United States: 1996-2013 estimates that, during this 18-year time period, academic-industry patent licensing bolstered U.S. gross industry output by up to $1.18 trillion, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) by up to $518 billion, and supported up to 3,824,000 U.S. jobs.

This new estimate demonstrates an impressive increase in economic benefits from the commercialization of academic inventions in the three years since BIO released a similar study. The previous report, conducted by the same independent expert team,[1] found that academic patent licensing between 1996 and 2010 contributed up to $836 billion to gross industry output, up to $339 billion to GDP, and to the support of up to three million jobs. Due to growth in academic-industry licensing activity, the newly released numbers show about a 20% increase in the licensing contribution to U.S. gross industry output and GDP, with an 11% increase in jobs supported.

And it gets worse for Mr. Wadhwa:

These economic impact estimates draw on licensing surveys conducted by the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), a recognized leader in supporting and advancing academic technology transfer globally. The latest AUTM survey for activities in 2013 vividly illustrates the annual contribution of academic patent licensing to the nation. It found:

• 818 start-up companies formed around academic patents (up 16% from 2012) – which is more than two new companies created every working day of the year;

• 4,200 start-ups in operation, mostly located in the same state as the parent research institution, creating regional economic development;

• $22.8 billion in product sales from commercialized academic inventions; and

• 719 new products introduced into the market (up 22% from 2012) – or more than two new products introduced every day of the year.

It’s doubtful the people commercializing these products, creating these desperately needed new jobs, and launching so many vibrant companies around academic inventions agree that patents and licensing thwart innovation.

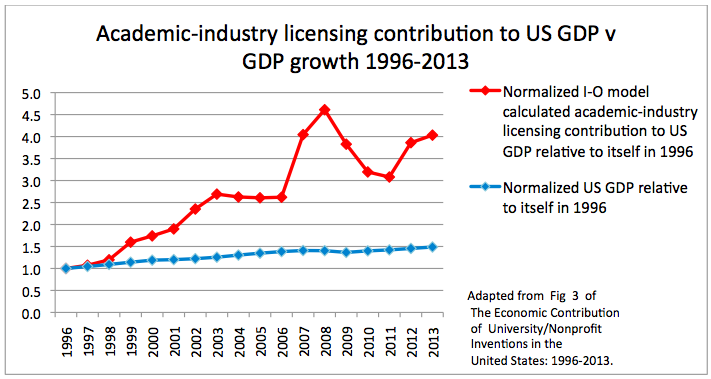

This chart from the white paper illustrates how academic- industry patent licensing has been performing compared to the rest of the economy:

Just in case anyone’s still buying Mr. Wadhwa’s theory, here are some additional points to consider. More than 70% of academic patent licenses go to small companies which historically are the drivers of our economy. Because these inventions are so early stage any company seeking to commercialize them must assume considerable risk and expense to go from the lab into the marketplace. History proves that without the incentives of patent ownership and licensing required to protect this investment potentially valuable discoveries will simply wither on the shelf. Unlike the Wadhwa hypothesis, there’s real data backing this up.

Before the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980 the government amassed 28,000 inventions made with federal support which had been taken away from the creating organization and warehoused in Washington where agencies sought to license them non-exclusively. Not surprisingly there were few takers.

In its hearings the Senate Judiciary Committee discovered that not a single new drug had been commercialized when the government took inventions away from academic institutions. If Mr. Wadhwa was correct these discoveries should have been rushing to the market because they were unencumbered by patent ownership and were freely available to all. But that didn’t happen.

The Senate Judiciary Committee brushed aside those making the same anti-patent arguments we hear today because they clearly didn’t work. The Committee determined that the U.S. could no longer afford to squander the fruits of billions of dollars of taxpayer supported R&D. The very first words the Senate Judiciary Committee wrote into Bayh-Dole were: “It is the policy and objective of the Congress to use the patent system to promote the utilization of inventions arising from federally supported research…”

The impact of the law was immediate. The Economist Technology Quarterly called Bayh-Dole: “Possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted over the past half-century… More than anything, this single policy measure helped to reverse America’s precipitous slide into industrial irrelevance.”

Because the Senate Judiciary Committee refused to heed critics like Mr. Wadwha we have 153 new drugs and vaccines fighting the scourge of disease as Bayh-Dole injected the incentives of patenting into the federal system. The U.S. leads the world in biotechnology because of university-industry partnerships founded on strong patent rights and effective licensing. The industry was created by patent dependent small companies which still dominate the sector. Many of our most successful biotech companies were academic start-ups formed around a patent.

It would be tragic if the Senate Judiciary Committee which created Bayh-Dole now undermines its effectiveness by approving the anti-university and small business provisions in the pending patent reform bill.

For example, fee shifting would force patent owners trying to stop infringers to prove based on vague, subjective language that their action is “substantially justified.” If the patent owner loses the suit they could be required to pay the other party’s legal costs. If the alleged infringer is a large, dominant company employing an expensive legal team these costs could be exorbitant enough to sink many start-ups and small companies.

Independent inventors, small companies and universities would have to think twice before turning to our legal system to enforce their patent rights. Without the threat of enforcement against copiers the patent system has little value. While this harms innovative companies of all sizes, it’s devastating to small companies trying to launch the disruptive technologies that make the United States the most dynamic economy in history.

The bill compounds the damage by dragging those funding or supporting innovators into patent suits where they can be held financially liable through a provision termed “joinder.” Thus, universities licensing small companies or forming spin-outs, venture funds, friends and family members, and others could find themselves hit with substantial legal bills when a patent owner they backed loses an infringement suit. It’s not hard to imagine the impact this provision will have on the willingness of investors to back small patent dependent companies.

President Lincoln said because the patent system protects the ability of the inventor to prevent others from freely using their discoveries it was one of the greatest advances in human history. By protecting the rights of the inventor Lincoln said the patent system: “added the fuel of interest to the fires of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things.” Clearly America’s greatest leader (who was a patent owner himself) held quite a different view than Mr. Wadhwa and his allies.

The U.S. patent system was designed as a shield protecting innovators from having their discoveries taken away by competitors who often dominate an industry and seek to stifle competition, or from those looking for a free ride after inventors have undertaken the considerable risk and expense of development. If the current bill is enacted our patent system will be turned on its head into something Lincoln would not recognize– a hammer to beat down innovators.

In his groundbreaking book The Mystery of Capital on why some countries are prosperous and others remain mired in poverty, South American economist Hernando de Soto argues that a key distinction is whether societies honor and encourage the ownership of property, both physical and intellectual. Hopefully, we won’t become the first country to voluntarily move in the wrong direction.

One of President Lincoln’s favorite humorists had a saying that applies to those now urging us to weaken or eliminate the patent system: “It ain’t ignorance causes so much trouble; it’s folks knowing so much that ain’t so.”

____________________

[1] The studies were done by a team led by Lori Pressman, an independent business development, licensing and strategy consultant who formerly served as Assistant Director of the MIT Technology Licensing Office, Mark Planting, former chief of research on the use of U.S. input-output accounts at the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis, Dr. David Roessner, Professor of Public Policy Emeritus, Georgia Institute of Technology and Senior Fellow, Science and Technology Policy Program at SRI International, Jennifer Bond, Senior Advisor for International Affairs for the Council on Competitiveness and former Director of the Science & Engineering Program at the National Science Foundation, and Dr. Sumiye Okubo, former Associate Director for Industry Accounts at the Bureau of Economic Affairs at the U.S. Department of Commerce.

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

Deborah

July 28, 2015 06:16 pmVersatility is surely viewed in the course of the entire range available in the market.

The features of all these Samsung mobile phones can be checked out

through various reliable mobile phone websites and the commercial website of Samsung.

Converting an i – Tunes song into a ringtone only takes a few

clicks.