Determining what compounds are obvious under the doctrine of “structural similarity” can be a daunting challenge, even for those of us with a chemistry or pharmaceutical background. Add the doctrine of “inequitable conduct” to the “structural similarity” brew, and the plot truly thickens. But there’s enough schizophrenia about the structural differences between one prior art compound called Schmutz X and another prior art compound called Compound 24028 in AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP v. Teva Pharmaceuticals, Inc. to make you reach for an antipsychotic drug like quetiapine which is at the heart of this case.

For those who are unfamiliar with the doctrine of “structural similarity,” a brief explanation is in order. Under the doctrine of “structural similarity,” if the claimed compound is deemed to be “closely similar” in structure to a prior art compound, the claimed compound will be held to be prima facie obvious (and thus unpatentable) unless it can be shown that the claimed compound possesses “unpredictable” or “unexpected” properties. For example, a claimed drug which has an ethyl group (two carbon atoms) might be deemed to be “structurally similar” to a prior art compound that differs only in that it has a methyl group (one carbon atom). To get you out of the “prima facie obvious” box, you usually must then show that: (1) the claimed drug possesses a pharmacological property that the prior art compound does not have; or (2) the claimed drug does not possess a “side effect” which the prior art compound does have.

Showing 2 (claimed drug does not possess “side effect”) was the one primarily at play in AstraZeneca. The patented drug in AstraZeneca, quetiapine (sold by AstraZeneca under the brand name SEROQUEL®), is classified as an “atypical” antipsychotic drug. An “atypical” antipsychotic drug does not produce the “side effect” of involuntary body movements (e.g., muscle spasms).

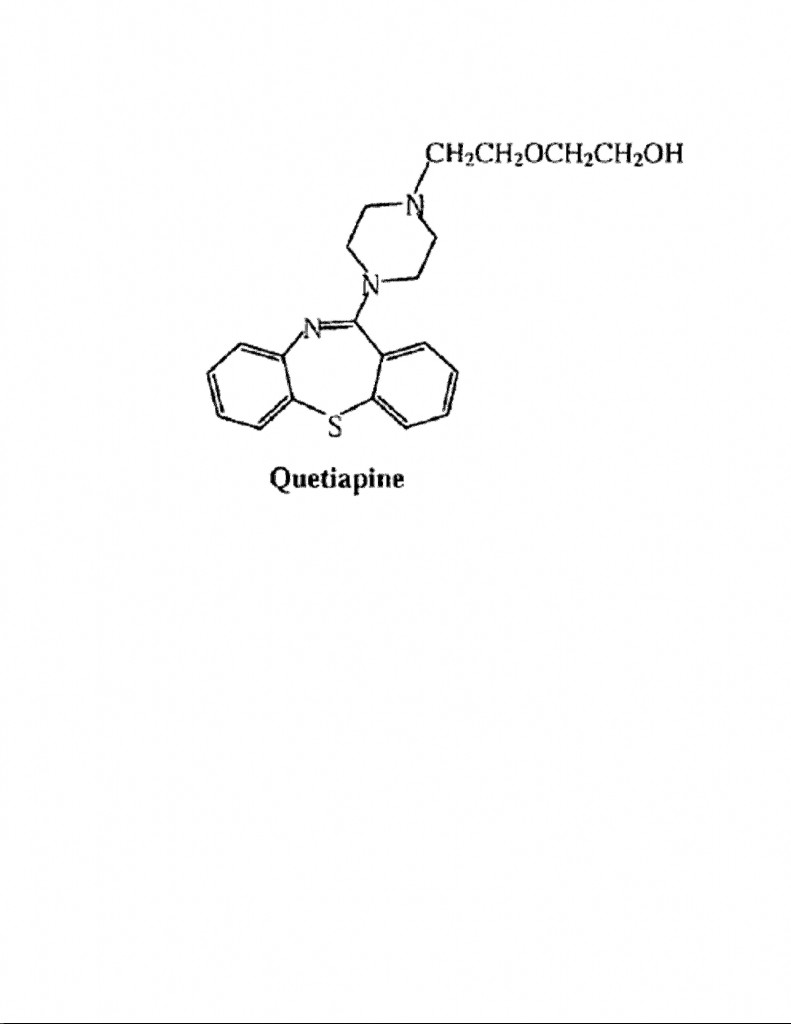

Quetiapine has the following structural formula:

Of particular importance in the above structural formula for quetiapine is: (1) the 2-hydroxyethoxyethyl side chainattached to the upper nitrogen of the piperazine ring (i.e., the hexagon-shaped ring having two “Ns” at opposite corners); (2) the absence of substituentsattached to the lower and left most benzene ring (i.e., the left most hexagon-shaped ring); and (3) the thiazepine ring (i.e., the lower, middle 7-member containing N and S members).

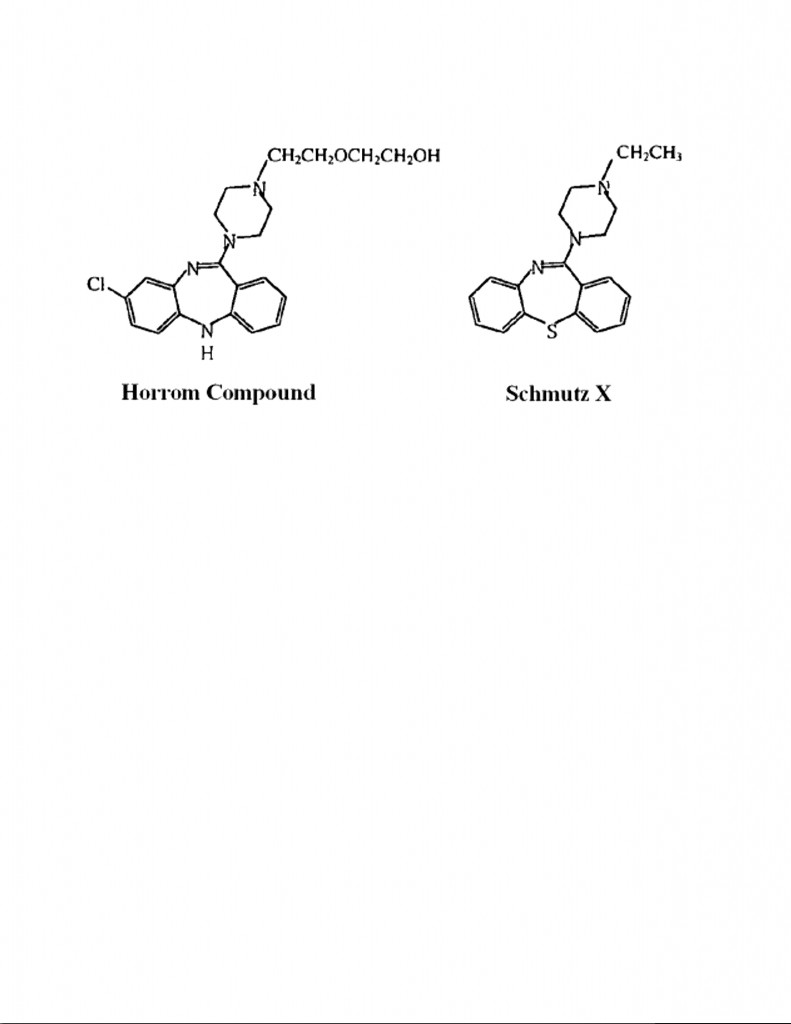

During prosecution of AstraZeneca’s U.S. Pat. No. 4,879,288 (the ‘288 patent) on quetiapine, two key prior art references were relied upon by the patent examiner in initially rejecting the claimed quetiapine as prima facie obvious: (a) U.S. Pat. No. 3,539,573 (“Schmutz II); and (b) U.S. Pat. No. 4,097,597 (“Horrom”). The key prior art compounds relied upon by the Examiner from these two references (the Horrom Compound and Schmutz X) had the following structural formulas:

The Horrom Compound differs from quetiapine in having a chlorine (Cl) substituent attached to the left most benzene ring, as well as replacing the S memberin the 7-member thiazepine ring of quetiapine with an NH member(i.e., a 7-member diazepine ring). By contrast, Schmutz X differs from quetiapine in having an ethyl side chainattached to the upper nitrogen of the piperazine ring.

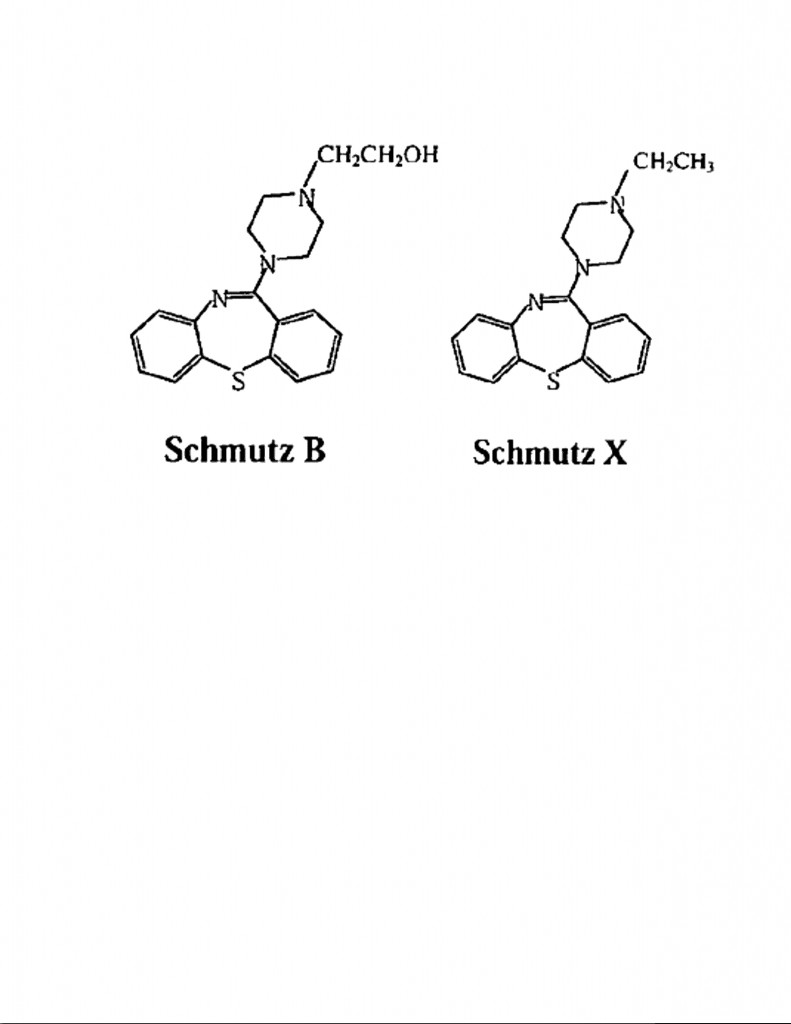

AstraZeneca submitted a Declaration from one of the inventors (the “Migler Declaration”) with data showing that the antipsychotic properties of the Horrom Compound were “typical.” But the prosecuting attorney for AstraZeneca was also alleged to have said that AstraZeneca did not have psychotic test data for Schmutz X, and that such data would be “very expensive to generate now.” Instead, AstraZeneca offered to substitute pre-existing internal test data for a different compound called Schmutz B which “the inventors believed was closer structurally than Schmutz X.” The structural formulas for Schmutz B and Schmutz X are compared below:

Schmutz B was considered closer structurally to quetiapine because of the hydroxyethyl side-chainattached to the upper nitrogen of the piperazine ring. (In this regard, compare the hydroxyethyl side chain of Schmutz B with the hydroxyethoxy portion of the side chain in quetiapine.) The data in the Migler Declaration also showed that the antipsychotic properties for Schmutz B were “typical.”

The Migler Declaration also included data on another compound from Schmutz II which was called Schmutz A. Schmutz A differed from quetiapine in that Schmutz A’s left most benzene ring was substituted with chlorine (like the Horrom Compound) and had a methyl side chain attached to the upper nitrogen of the piperazine ring (similar to the ethyl side chain for Schmutz X). The data in the Migler Declaration showed that Schmutz A was inactive for antipsychotic activity, so “no test for atypical side-effects was conducted for Schmutz A.”

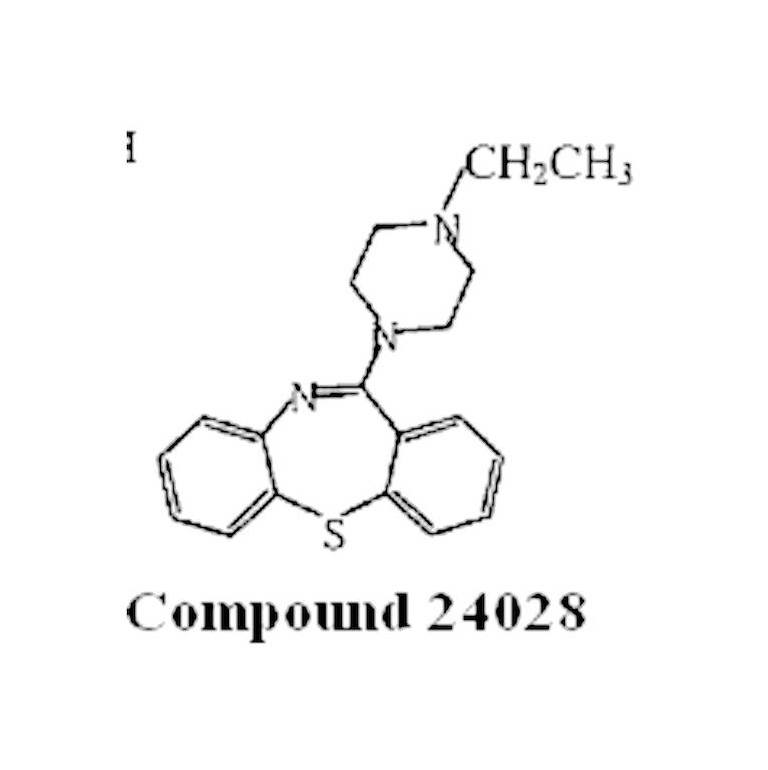

Everything that happened in the prosecution of the ‘288 patent, including the submission of the Migler Declaration, appears to be straightforward until you consider Compound 24028, at least as shown in AstraZeneca. Compound 24028 (which was described in the Schmutz II reference) is shown in AstraZeneca as the following structural formula:

Now for the “mysterious” part of AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca had internal test data on Compound 24028. But exactly what this “internal test data” comprised is never mentioned in AstraZeneca. In addition, Compound 24028 was characterized by the alleged infringers (Teva and Sandoz) as being “structurally similar” to Schmutz X, and, like Schmutz B, “equally close” to the claimed quetiapine. But, when you compare the structural formula for Compound 24028 shown in AstraZeneca with that of Schmutz X above, what is puzzling about this characterization is why these two compounds aren’t considered structurally identical. Could it be that there’s a typographical error in the AstraZeneca, and one of the structural formulas for Compound 24028 and Schmutz X should be different? If so, then which one is wrong and what should it be? But if the structural formulas for these two compounds are correct as shown in AstraZeneca, then Judge Newman’s opinion (discussed below) takes on a more surreal aspect.

So much for the relevant prosecution background on the ‘288 patent. Teva and Sandoz each filed abbreviated new drug applications (“ANDAs”) for approval of their generic versions of quetiapine, including a Paragraph IV certifications that the ‘288 patent was invalid and/or not infringed. That allowed AstraZeneca to sue both Teva and Sandoz for infringement of the ‘288 patent. In response, Teva and Sandoz alleged that the ‘288 patent was obtained by “inequitable conduct” during prosecution. The district court granted AstraZeneca’s motion for summary judgment that there was no “inequitable conduct” in the prosecution of the ‘288 patent.

On appeal, Judge Newman (speaking for the Federal Circuit) framed the “inequitable conduct” issue as “the extent to which the patent applicant [AstraZeneca], having fully disclosed the relevant prior art and having provided comparative data to the satisfaction of the patent examiner, must also present any additional unpublished information [e.g., internal test data on Compound 24028] in the applicant’s possession concerning other less structurally similar compounds, and must also synthesize additional compounds for comparative testing (emphasis added).” Teva and Sandoz again argued that the Migler Declaration was “deliberately misleading” because AstraZeneca failed to provide internal test data which showed that compounds other than quetiapine possessed potential “atypical” antipsychotic activity [i.e., Compound 24028].” In particular, Teva and Sandoz argued that “AstraZeneca misrepresented that the ‘atypical’ properties of quetiapine were unexpected.”

But Judge Newman didn’t see it that way. First, Judge Newman observed (correctly) that “[n]o relevant reference is asserted to have been withheld.” Second, Judge Newman said that Teva and Sandoz “do not assert that AstraZeneca had data for Schmutz X and withheld it,” nor “do they argue that Schmutz X is in fact atypical, and no data are presented to this effect.” Instead, Teva and Sandoz “seem to argue that because of the structural similarity between Schmutz X and Compound 24028, Schmutz X could be atypical, and thus should have been synthesized and its antipsychotic properties tested.”

Judge Newman conceded that “there may be situations in which the failure to conduct specific tests of specific compounds can be criticized,” but that “in this case there was no evidence that the information gleaned, if such tests had been conducted, would have been material to patentability.” In fact, it “[had not been] disputed that it was unpredictable whether a given compound would exhibit atypical antipsychotic properties.” Instead, “[t]he record demonstrates that structural similarity is not a predictor of whether antipsychotic behavior would be typical or atypical.” As Judge Newman put it, Teva and Sandoz had “made no showing as to whether the structural similarity between Schmutz X and Compound 24028 would establish whether Schmutz X would have atypical properties.”

Judge Newman also accepted that “the patent examiner did not dispute AstraZeneca’s scientific position, and accepted the proffered data on Schmutz B as the closest prior art.” Accordingly, Judge Newman ruled that “AstraZeneca’s substitution of Schmutz B in place of Schmutz X was not a material misrepresentation, and the non-provision of the data on Compound 24028, which is structurally less similar to quetiapine, was not a material omission.” And like the district court, Judge Newman concluded “that the evidence cannot support a finding that AstraZeneca misrepresented or omitted material information.”

As noted above, a comparison of the structural formulas for Schmutz X and Compound 24028 as shown in the AstraZeneca suggest that they are not simply “structurally similar,” but are, in fact, structurally identical compounds. As also noted above, what we may have here is a typographical error, and what Judge Newman says could make perfect sense regarding the “inequitable conduct” issue. If that is the situation, hopefully the Federal Circuit will issue an appropriate correction notice.

But here’s a scarier thought: what if the structural formulas for Schmutz X and Compound 24028 are correct as shown in AstraZeneca? In other words, what if Schmutz X and Compound 24028 are, in fact, the same compound? If that’s true, then there’s something seriously amiss with Judge Newman’s opinion. In fact, Teva and Sandoz have a serious beef as to why the “omitted” internal test data for Compound 24028 was not considered “material.” As noted above, AstraZeneca stated during prosecution of the ‘288 patent that they didn’t have such test data on Schmutz X and that generating such test data would be “very expensive.” Accordingly, the failure to submit, or to even acknowledge, this internal test data for Compound 24028, if it’s truly identical to Schmutz X, would seem to be extremely significant regarding the “inequitable conduct” issue.

Assuming that Compound 24028 and Schmutz X are, in fact, the same, and further assuming that AstraZeneca‘s internal test data showed Compound 24028 had “atypical” antipsychotic activity, would the submission of this test data have hurt AstraZeneca‘s case for the patentability of quetiapine based on Schmutz B being more “structurally similar” than Schmutz X? Not necessarily. In fact, given that Schmutz B had “typical” antipsychotic activity, data showing “atypical” antipsychotic activity for Compound 24028 (and thus Schmutz X) would have been entirely consistent with the difficulty in predicting “atypical” antipsychotic activity amongst compounds that appeared, at first blush, to be “structurally similar” to quetiapine.

But what we need to solve this “mystery” is clarification from the Federal Circuit as to what, if any, differences there are between the structural formulas shown for Compound 24028 and Schmutz X in AstraZeneca. Without that clarification, we don’t know whether Judge Newman’s opinion got it right on the “inequitable conduct issue, or perhaps very wrong.

*© 2009 Eric W. Guttag

![[IPWatchdog Logo]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/themes/IPWatchdog%20-%202023/assets/images/temp/logo-small@2x.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Patent-Litigation-Masters-2024-sidebar-early-bird-ends-Apr-21-last-chance-700x500-1.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WEBINAR-336-x-280-px.png)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2021-Patent-Practice-on-Demand-recorded-Feb-2021-336-x-280.jpg)

![[Advertisement]](https://ipwatchdog.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ad-4-The-Invent-Patent-System™.png)

Join the Discussion

One comment so far.

TT

October 28, 2009 02:06 pmDoes it strike anyone else as funny that what we called the scum floating on top of our reaction flasks or any other obvious impurity (no pun intended) was schmutz or schmutz X for “unknown schmutz”?